Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas Breault

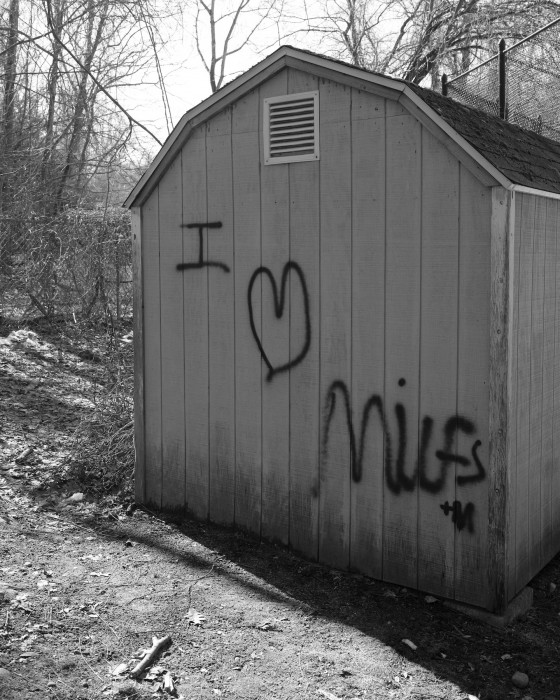

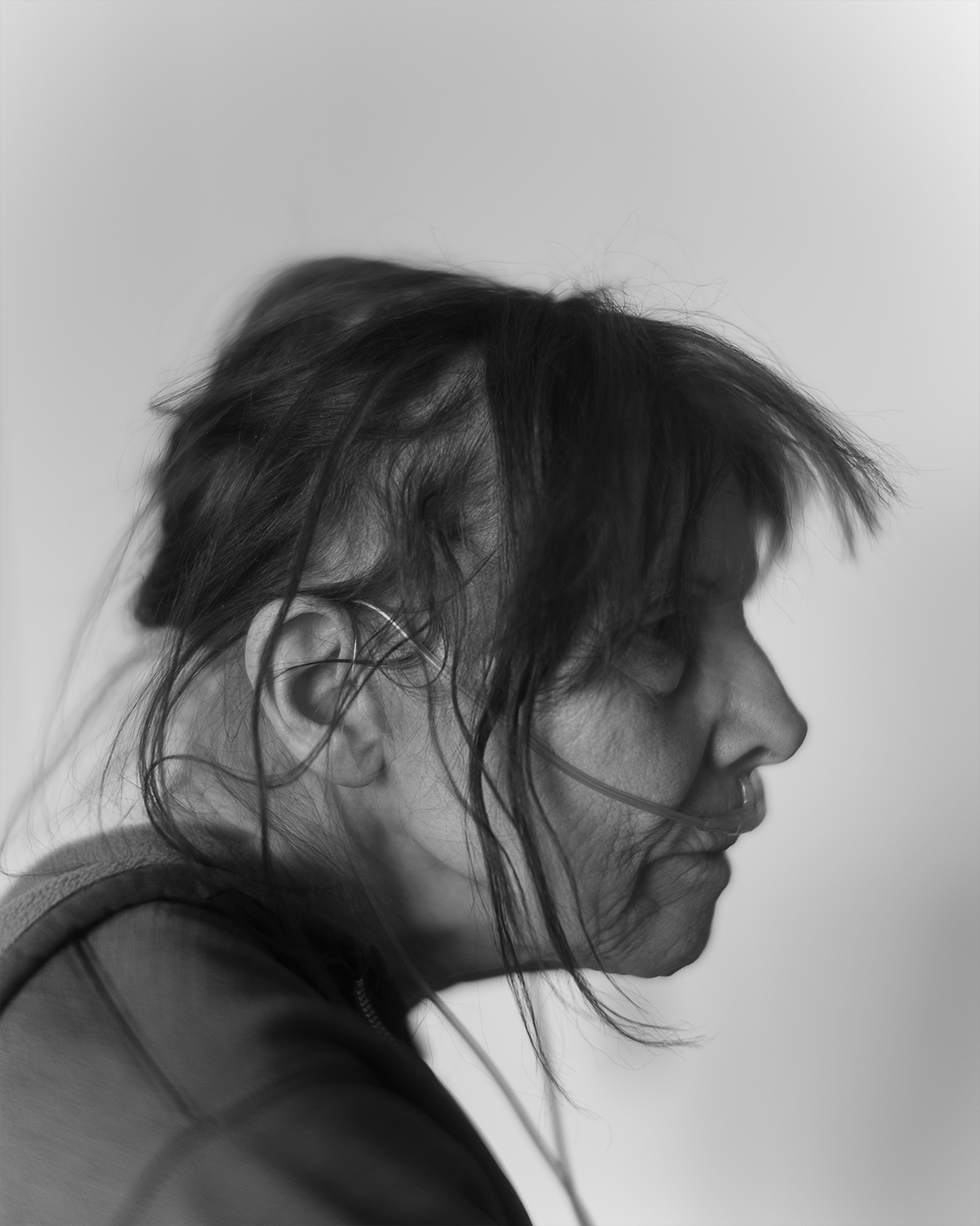

Jake Corcoran is a young photographer from New York City whose work is thoughtfully direct. His photographs have a songlike touch of honesty that can’t be created through technical editing or camera tricks. Corcoran’s portfolios often link landscapes with portraits, eliciting a hollowed sense of absence through his meticulous compositions of interrupted and emptied spaces. His attention to textures and limited light sources points affectionately to the unrelenting indicators of time, such as worn infrastructure and wrinkled faces, to focus on the humble pleasure of seeing in its own right.

I first encountered Corcoran and his work while jurying the spring exhibition of the Curated Fridge in Somerville, Massachusetts. The hundreds of photographs submitted for that round reflected the weight of our current climate, with oscillating themes of death, loneliness, and the peculiarity of trying to remain sane while surrounded by insanity. I kept circling back to the five images Corcoran submitted because of his ability to connect seemingly unrelated subjects that lack an obvious linear narrative yet possess a spirit of belonging to each other. It felt like trying to describe the plot of your favorite book to someone who hasn’t read it—pockets of impactful scenes crucial to a larger story, each open to a different interpretation by the viewer. There is a maturity to the mystery in how Corcoran makes a photograph, using subtlety and restraint that seem to stem from always having his camera in hand. When I met him at the reception for the Curated Fridge, he did indeed have his camera with him and was asking for suggestions of places to photograph during his brief time in Boston.

Corcoran subtly shifts the reality of the ordinary into something resembling a film noir romance—capturing the softer moments between the obvious plot points. He understands how those in-between moments can tell a story of their own. His work is not overtly somber, but rather a meditation on the lingering humanity within bare spaces. Photography offers a limited view—a contained notion—in which what is excluded can have as much impact as what is included. His subjects are worn and broken in, focused on the decline of something that was once new and cherished. He is, I think, a great example of the difference between someone who is merely a photographer and an artist who uses photography. The distinction might sound academic, but Corcoran creates images that stretch beyond the seemingly ordinary and avoids overly dramatic gestures to invite lyrical considerations of how an image can contain its own emotional weight.

Do you think your work relates to the idea of the “American Dream” or American culture based on your subjects?

Yeah, for sure. I would say America is the main character in my baseball work. Baseball is a tough game, it dangles the illusion of success, but the reality of it is largely failure. In 2025, the “American Dream” feels much the same.

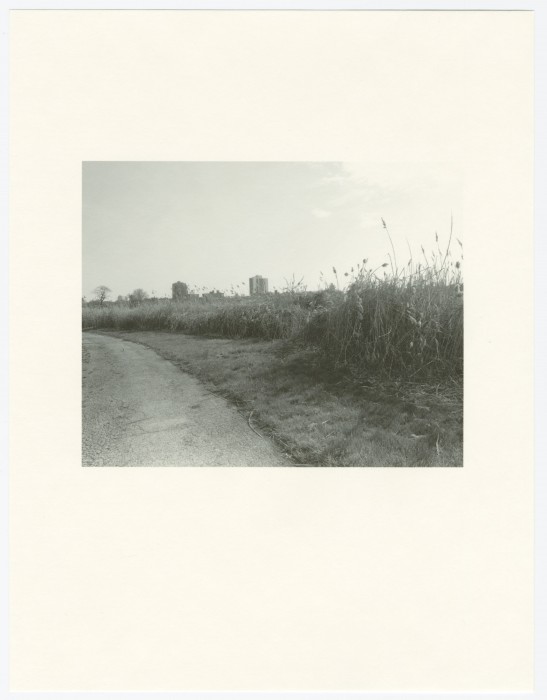

I found that baseball fields mirror an area’s socio-economic condition almost perfectly. Rusting fences echo the decay of shuttered factories, and the overgrowth around abandoned diamonds tells the same story as the collapsing industries nearby. Baseball and the U.S. grew up together and its loose, unpolished, and often gritty character still reflects the realism of the American experience.

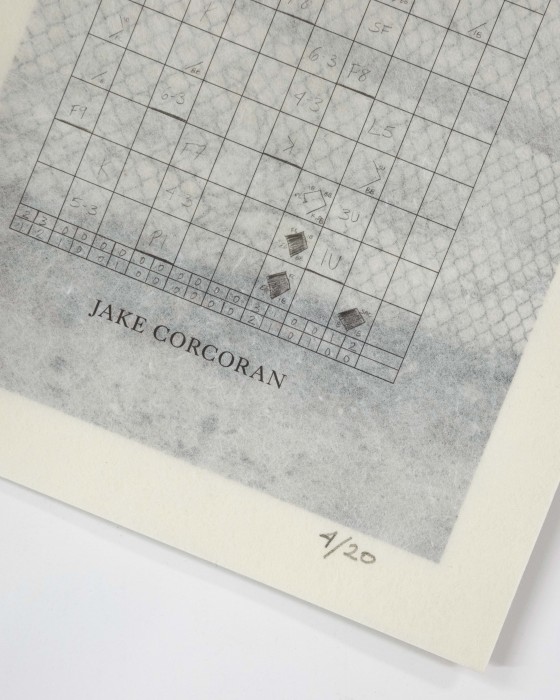

The New Topographics movement is among some of my favorite photographic work. I just naturally resonate with it, and would’ve photographed that budding era of the man-altered landscape if I could have. Now it’s too late. For me baseball fields scratch part of that itch. I’ve made a rule for myself to shoot every backstop on a baseball field I encounter the exact same way: f/8, 45mm lens standing on the pitchers mound. It’s like the Bechers’ approach to baseball fields. Objective, descriptive and hopefully a little ironic.

In my undergrad thesis project Shades of Another Water I spent time studying the opioid crisis in Ohio. Sitting to listen and learn from people at different stages in their recovery felt really important. For a lot of the subjects, their version of the American Dream was to stay alive, stay out of prison and hold down a job long enough to get a place to stay. It was an extremely difficult process to navigate, but doing so magnified so much injustice in American culture, but, simultaneously, so much affection.

What draws you to black and white versus color photography?

I remember someone important saying that color photography is obsolete because no matter how hard it tried it could never look as good as real life. B/W doesn’t try to mimic the world, it translates it into its own language. BW has its own thing going on. That made a lot of sense to me at the time, and still does, although there are color photographs that, of course, look much better than real life. It really just comes down to the moment I’m in right now. I enjoy how dirt and trees and water and detritus look in black and white and that’s mostly what I photograph so it works out.

You are young in your career as a photographer, where would you like to see your work go next?

I actually want to be a little less intentional with my work. There’s so much possibility and creative power in letting go. So I guess knowing when to wrangle certain elements together and when to let loose ends exist is something I’m trying to work on. It’s probably cliche to say, but, art education teaches us to make full justification for every decision and image we make. That can be not only tiring, but limiting.

Kind of counterintuitively, I’ve started writing about my work on Substack. So far I’ve used it to gather my thoughts on past projects. It’s been difficult but exciting. Who knows if it’ll go anywhere.

So, making more, failing more and justifying less.

What inspires your work outside of photography?

I wish I could say films or music but I don’t see those things really making their way into my work. Maybe the music I listen to (usually very quietly on my headphones) when photographing subtly points me to certain scenes/subjects/feelings. Certain short stories and literary passages get me excited about being out seeing and photographing. I’ve been into Raymond Carver’s short stories a lot recently. They’re good for the subway to work in the morning when I’m in the mood for a little existential dread. Carver is like the perfect concoction of devious, tender, brutal, and nothingness. It doesn’t hurt that the Vintage Books collections have Todd Hido pictures on the covers.

Truthfully, almost all of the conscious inspiration in my work comes from photography. For a while now it’s been Raymond Meeks, Tim Carpenter, Tim Davis, Barbara Bosworth, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Mathew Genitempo, Andrea Modica, Robert Adams, and John Gossage mainly. Their work often makes me feel like they’ve achieved this effect of containing everything – every idea worth considering – is all in there somehow. Or, in other words, their pictures feel so big and consuming while being often so small.

What interested you about the Curated Fridge?

Well, for one it was free! So many photo shows and competitions charge like $35 for one image and it’s just not realistic. More importantly, though, I was drawn to how authentic and community-driven the Curated Fridge is. Mailing in a set of small prints certainly felt more fulfilling than uploading a 1mb file into a black hole on the internet. For 10 years now photographers have come from all over to look at photographs on Yorgos’ fridge. That alone should tell you how much TCF resonates with people.

Jake Corcoran is a photographer born and living in New York City, who graduated from Kenyon College in 2023. Jake uses the camera as a way to explore personal and social histories through often ambiguous means. His sparse photographs unfold as a result of the viewers’ attentiveness and patience. Jake’s recent work on baseball uses a unique formalism to gently arouse emotional introspection and increased appreciation for the world around us.

Follow Jake Corcoran on Instagram: @mr.mju2

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the MFA Boston, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, and the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts. In addition to being an artist, Breault writes about art, curates exhibitions, and teaches photography at different colleges.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025