Photographers on Photographers: Lydia McNiff in Conversation with Carmen Winant

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today we start with Lydia McNiff who selected Carmen Winant to have a dialogue with. Thank you to both of the artists.

I was first introduced to Carmen Winant through my aunt, who knew I was deep into researching and creating work around women’s health and feminist perspectives. When I encountered Carmen’s practice, I immediately felt a profound resonance between her work and my current series, Visceral. Her ability to draw from archival materials and reframe them through a feminist lens struck a chord with me–not only aesthetically, but conceptually.

Carmen’s process of excavating found photographs and recontextualizing them is both rigorous and poetic. She transforms existing imagery into new, often urgent narratives that spotlight women’s lived experiences–stories that are too often overlooked, obscured, or forgotten. Through this process, she not only reclaims visual histories but also amplifies them, placing these images before audiences who might otherwise never encounter them.

In a time when women’s rights, bodily autonomy, and freedom are increasingly under threat, Carmen’s work feels especially vital. Her images speak to resilience, agency, and the power of collective memory. They are visual declarations that bear witness to both struggle and strength. Carmen Winant’s practice is a living testament to the endurance of women in the face of erasure, chaos, and resistance–and a reminder of the necessity of keeping these narratives alive.

Carmen Winant (b. 1983, San Francisco, CA; based in Columbus, OH) is an acclaimed artist, writer, and educator whose work challenges the traditional narratives surrounding women’s bodies, labor, health, and liberation. She holds the Roy Lichtenstein Chair of Studio Art at the Ohio State University, where she also teaches. Winant has been recognized with a Guggenheim Fellowship in photography (2019), a Foundation for Contemporary Arts award (2020), and honors from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (2021).

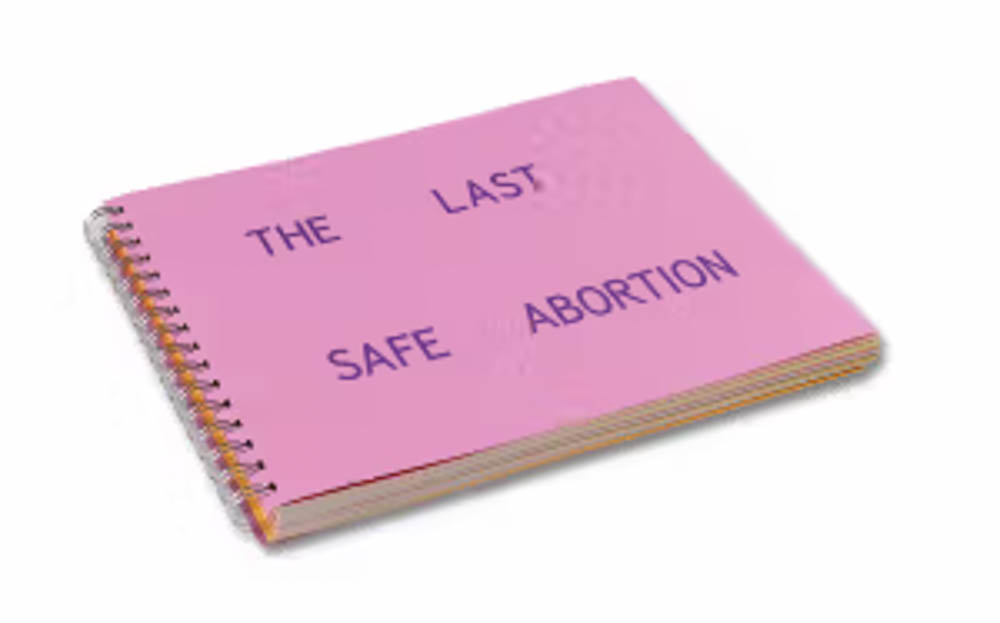

Her work has been exhibited widely at major institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, ICA Boston, the Wexner Center for the Arts, SculptureCenter, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and MUAC in Mexico City. Her artist books include My Birth (2018), Notes on Fundamental Joy (2019), Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now (2021), Arrangements (2022), A Brand New End: Survival and Its Pictures (2022), and The Last Safe Abortion (2024).

Instagram: @ carmen.winant

Lydia McNiff: Hi Carmen, thank you for agreeing to participate in this interview. I’m very excited to learn more about your artistic practice. To begin, could you share a little about how you first fell in love with photography and what continues to inspire your creative work? What are some of your earliest memories with photography?

Carmen Winant: It’s kind of an old story, but I was always compelled to be an artist. I feel like so many artists feel this way, before they realize that that had a name, but as a young person, I was always drawing. I didn’t have access to the camera or understand its technology. But looking back now, I realized that I lived inside–even if I wasn’t making photographs as a teenager and a preteen–I was obsessively collecting photographs, ripping them from magazines that I had access to.

So the photographs themselves weren’t that remarkable, but I was really into collecting types or sets of advertisements, which is what I had access to. There would be these Absolut Vodka ads and Got Milk campaigns, and they were types, you know–they were always photographed by the same person or in the same way. I would rip them out of magazines at doctor’s offices and eventually I got a few of my own subscriptions and would be ripping, ripping, ripping.

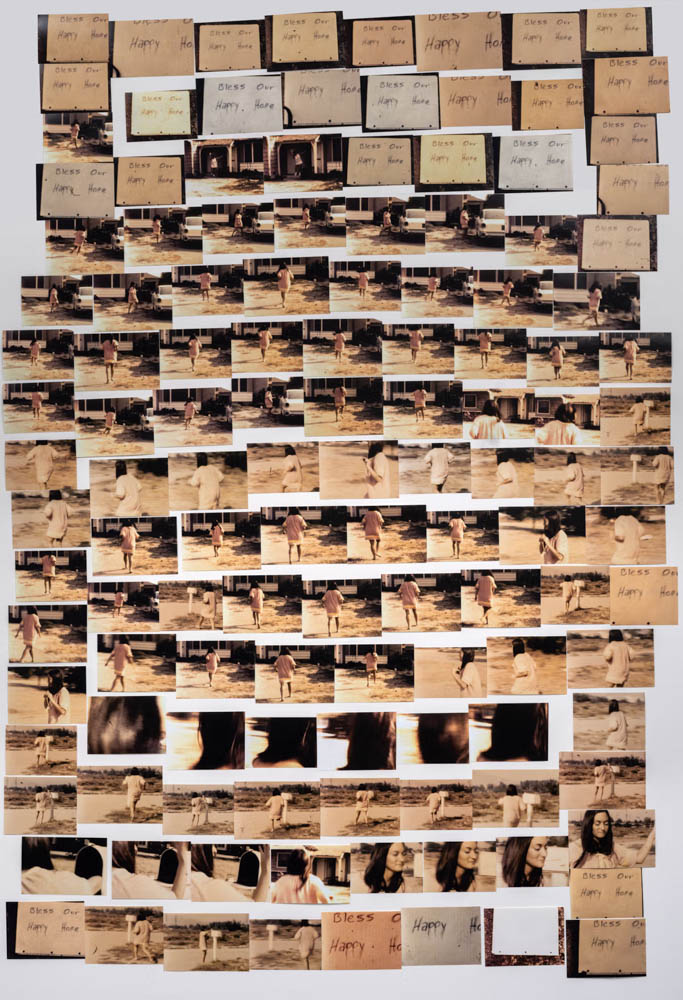

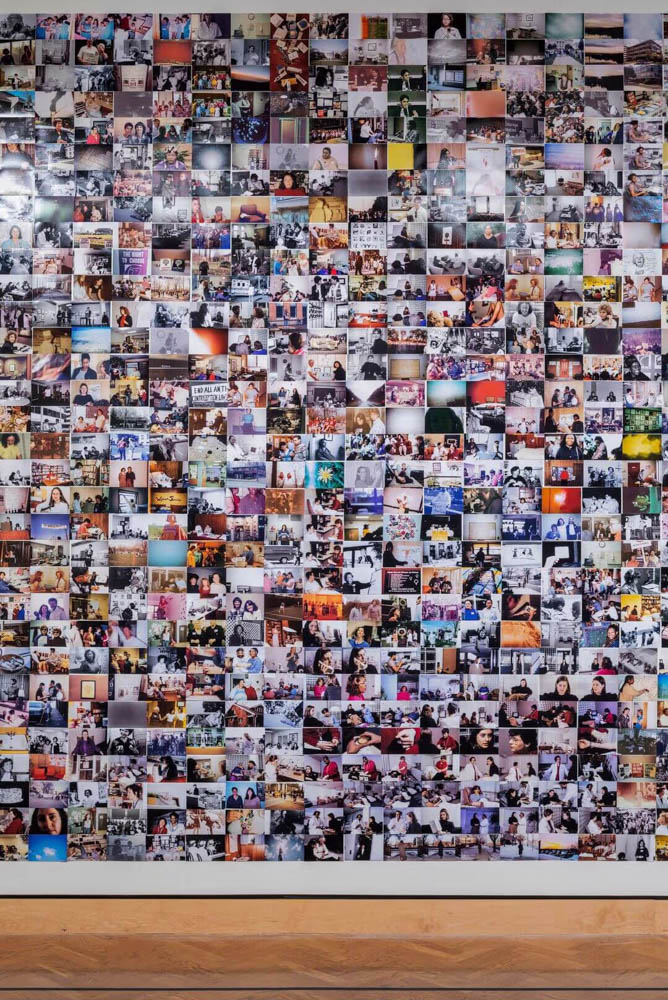

Then, I pasted them on my wall so that the entire wall was covered. You couldn’t see any of the purple and pink painted walls underneath, which was my childhood decision that I never amended. And then I would just layer and layer and layer.

I grew up in Philadelphia, and my parents moved out of that house about 20 years ago and moved to California. I have no pictures of that room. My mom describes when they moved out, they had to take a blade to the top corner and then just peel them down like a skin. So looking back now, I think, oh yes, of course that was photography.

I didn’t relate to it as photography because I wasn’t making my own pictures, but I was obsessed with collecting them, looking at them, arranging them, sort of living inside of them. And then in fact, when I did go to college, I immediately fell into that way of being an artist.

It’s hard to look back at one’s own wavy trajectory and pinpoint certain moments. But it’s interesting how our impulses so often are the same. I’m 41 years old now, I have the same impulses as when I was 12 and a half, you know, in that regard.

Lydia McNiff: Your process, as you mentioned in your previous answer, involves a lot of collaging found images and archival material that come directly out of the second-wave feminist movement. At times, I’ve seen that you’ve combined some of your own images with those found ones. How do you navigate the balance between honoring the history behind those found images and incorporating your own photographs to shape new narratives?

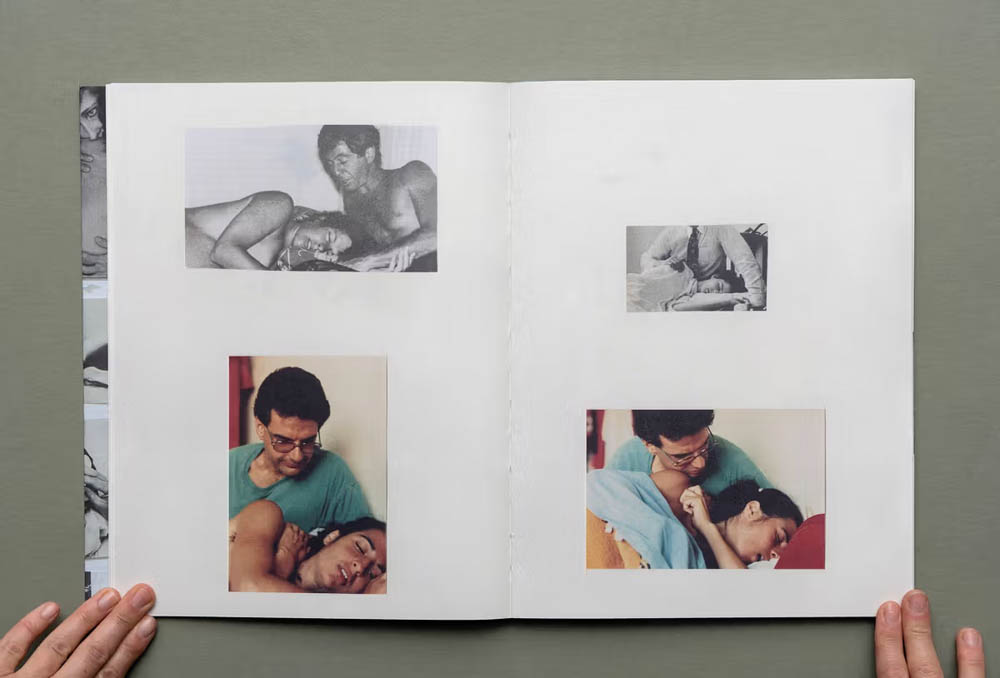

Carmen Winant: Good question. Incorporating my own photographs is a new phenomenon for me. I’ve been experimenting with it for years and years. I really refused that idea. I was really interested in turning towards other people’s pictures, and I didn’t find my own pictures as interesting. So it wasn’t a moral judgment–I just wasn’t compelled in that direction.

Maybe there was a slight moral element in that I wanted to reimagine these sweeping histories that predated my own history, and it felt weird to insert myself as a kind of protagonist.

It wasn’t until 2018, when I was working on My Birth for MoMA– both the book and the installation–that I started playing with the idea of using family pictures, using images from my own delivery of my children. It made me uneasy, to be honest. I just had really circumnavigated that way of working for so long. And then, of course, there’s a third variable that I could mention, which is the most obvious one: you stand to exploit or expose yourself or people that are closest to you and your family.

So I wanted to avoid that problem, but it caught up with me, and that was an interesting experiment with My Birth, and it gave me the kind of confidence to continue asking that question–the same question that you’re posing.

It’s really project by project, like the project that I worked on a few years back now around domestic violence advocates and support workers. I made some of my own photographs for that project, but none of them centered my personal subjectivity.

Then, when I worked on the abortion project after that–which borrowed a lot of strategies from the domestic violence project–I did sort of center myself. I not only made photographs for that project as I had done for the domestic violence project, but I was in many of the photographs.

In that case, I was thinking a lot about how I was a part of the story. I couldn’t deny that anymore, you know, however uncomfortable it made me–both in the sense that, historically, I was benefiting from the work that these women did a generation, two generations, in some cases three generations before me. But also that I’m here as the artist, I’m making editorializing decisions, I’m crafting the story–and to pretend otherwise is to be disingenuous.

So that was the most exposed I have felt in a project. It has continued to surprise me that when I talk to people about the project, they always want to talk about that piece of it, or feel interested or attracted to that piece of it.

That is exactly as you’re putting it too–what is this balance? When do we start to register you as an artist, as a woman, as the curator in some sense? So I’m still working it out. It’s project to project. If you told me ten years ago that I would have been making my own photographs, much less that I would have been in those photographs, I would have really balked at that idea.

So it’s a way to evolve the practice, but I would be lying if I said that I was totally comfortable with it.

Lydia McNiff: Thank you for sharing that. I’m also really curious about what your research process is like and how you come up with a concept for each of your projects. Can you walk me through your research process? How much time do you typically dedicate to research when developing a project?

Carmen Winant: Sure. It again varies from project to project. I just made and put up a show a few days ago with the gallery that I work with in Chicago that was a very Studio E project.

It was very–I think in part because I wanted a little break between research-heavy projects. Although I guess in a demonstrative way, that did require researching a lot of material to pull into the studio. Research is a really meaningful substrate in my practice.

It’s interesting actually. I work at OSU, which is a research institution, and so everybody–all of the faculty, no matter what their field–describes what they do as research. So the engineers and the dancers will both say, “my research is…,” and I think sometimes that’s an ill-fitting descriptor for people in the arts, but they use it because that’s the parlance.

And sometimes I hear other artists, my colleagues, who are like, is that actually right to call what I’m doing research?

In my case, I’m like, wow, do I really belong in a research institution? Because I really research like an academic. And I come from a family of academics. My dad is a sociologist, my sister is a professor of English, my brother’s a professor of history–labor history. And he, in fact, taught me how to research an archive in a way that I had never known.

So I feel like I get the best of both worlds, because I have this sort of–I mean, it’s imperfect–but I’ve developed a kind of working intelligence around how to research, let’s say specifically in archives. Although there’s different ways that research is animated. Also, because I’m an artist, there’s no best practices. So I can cut certain corners or make up certain ways of contending with even the archive, much less this broader category of research.

I just want to start there, because I feel like we use that word as artists in so many different ways–as we should. We’re not limited.

I have friends–my dear friends here in Columbus are both anthropologists–and they have such specific ways that their field enables them to research, or there’s such specific protocols. And that’s not a bad thing. Sometimes I wish I had more best practices. But I really feel lucky that I get to invent what research looks like, while using the skills and tools that I have at hand.

I’m not an artist who’s making a five year plan. I don’t know that there is any artist who does that. That’s like, “OK, first, I’m gonna do this and then I’m gonna work on this,” or something. I’m responding to the conditions of my life–by which I mean both in large part being a mother. My kids are 7 and 9 now. And the seasons of life, relative to, frankly, the care work that’s demanded of me–but also the political conditions in which we’re embedded and how those are forever shifting under our feet.

I was just saying to my partner the other night, what if I’m always just one step ahead of myself? What if I run out of ideas? I just feel like I’m living in the present tense. And I am lucky that I’m in a moment in my career trajectory where sometimes things will fall on top of me, you know, in the best possible way. I’ll get an assignment that comes with a certain kind of a prompt.

That was actually the case for how I entered into the abortion work. I was commissioned by a very large foundation in Cleveland–a city just northeast of about two hours to Columbus–by the Gund Foundation to work on a project on reproductive justice. And so I started to make some photographs, and I started to meet some abortion care workers, specifically in Cleveland.

I came into their archive. It was unbelievable. I felt like, oh my god, if this one abortion clinic in Cleveland has thousands of photographs, what do other clinics have? How broad do I want to expand this? Should this just be the Midwest? Should this just be Ohio?

Some of that is contingent on who else I know and who else those folks will be willing to introduce me to, because that’s not a kind of project where you can strut into a clinic and start taking pictures or going through boxes. So it moves at the speed of life a little bit.

It was really amazing to work on that project and realize how much it had in common with My Birth.

In some ways, it was a closed circle with My Birth, which I had made in 2018–eight years before. They were both projects that contended with reproductive agency and dignity and representation.

That’s not something I’m mapping out at the beginning, so there’s a certain amount of self-trust involved in putting one foot in front of the other and understanding that one’s life is reconciled with one’s life.

The work that I do–caring for my kids–has to do with my political organizing work, has to do with my teaching work, has to do with my studio work, and just sort of letting them inform each other.

It sounds a little bit hackneyed, but I don’t know how else to describe it. That’s really how I come into projects–and then sort of let them evolve and speak back as I go.

Lydia McNiff: Your work has been a powerful catalyst for the feminist movement. In an artist talk at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, you asked the crowd, “How does feminism find us?” So I’m curious–how did feminism find you? And why did you choose to center that around your photographic process?

Carmen Winant: I love that language. I wish that I wrote that. I was quoting Sara Ahmed, whom you might be familiar with, from her 2017 book Living a Feminist Life. I’ve always been so attracted to the way that she writes about–just that–living a feminist life. She doesn’t occupy feminism in the ivory tower. For her, it’s not a political theorem; it is praxis. It lives in our bodies, in our lives.

All of her metaphors are very bodily. It’s all about our marrow and our flesh and our pores, and even to this language–”When did feminism find you?” –as if it’s an animate force.

And so I always return to that text, and it really informs how I move through the world.

When did feminism find me? It’s another question that’s not dissimilar from your first one about early memories of falling in love with photography, where it feels like there’s not one revelatory moment–there’s like a million pinpricks, in the best possible way.

The easiest way to respond to that is to say that I grew up in a very feminist household. Both of my parents declaratively talked about themselves as feminists. My mother is now retired, but she worked in women’s international reproductive health, so less in the United States. And so it was the water I was swimming in.

But I can’t say that as a young person, I was that awake to it. When I was in college–I went to UCLA–I don’t know if I took a single course in Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies. But I took a lot of art history classes. I took some Black Studies and Radical Black Thought classes at the same time that I was learning the camera, in a really dedicated way.

So for me–this sounds a little esoteric–but it sort of fused. I was learning about what it meant to be a radical person or a feminist, or somebody who made propositions of our world, or understood our world as unfair and unbearable. And at the same time, I was really learning the camera and becoming dedicated to it. So to me, that all locked in at the same time. It took me a long time–longer than it should have.

In fact, I remember when I was at UCLA, there was this really amazing feminist–kind of like guerrilla feminist–magazine, and I was really intimidated by them. I was not in their clique–not that they were exclusive or anything. And I finally went to one of their meetings. I still remember–we had Ethiopian food on Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles, which is Little Ethiopia–and I was so intimidated by them.

And they were by no means intimidating–I was just me. They were welcoming and smart and interesting and curious. And I didn’t speak the entire time, and I didn’t ever go back.

So looking back, I’m like, why did it take you so long to stake out this territory? So it was really in feet and inches rather than in meters and miles that I came to–as Sara Ahmed says–find feminism as an animating force. I think all these little pieces become situated within–they alchemize inside of us.

By the time I was in my mid-20s, I was really starting to orient myself politically in that direction.

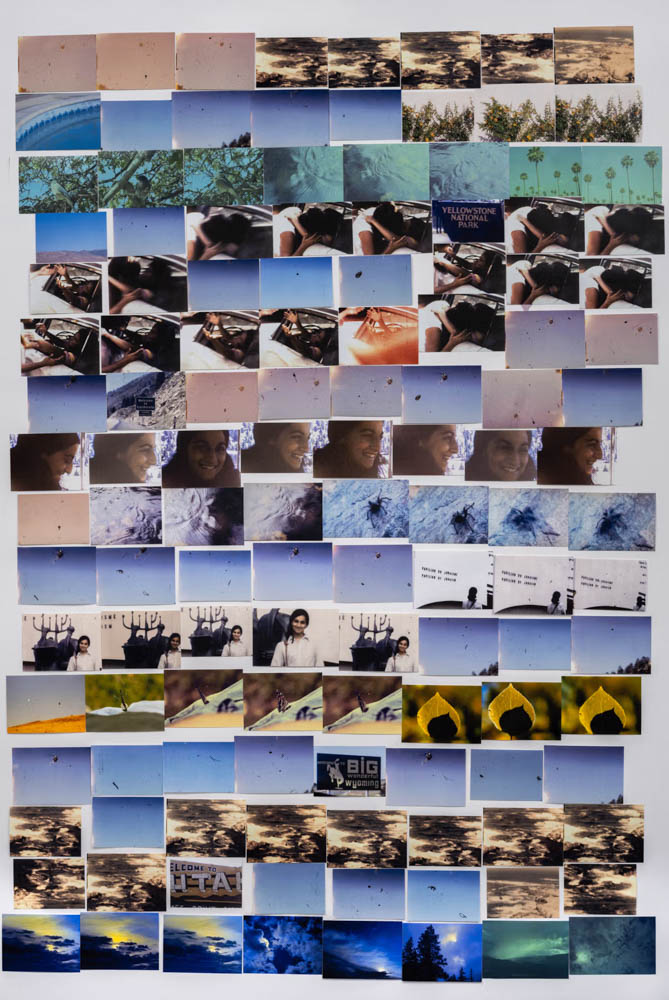

Lydia McNiff: You kind of answered my next question in your previous response, but in speaking about your project My Mother and Eye, which is one of my personal favorites, your mother, Debra, recalled feeling, “that the world was being reborn, that we were reinventing the world,” during her trip from Los Angeles to Niagara Falls with her friend Judy. How did her perspective–and her example–shape your understanding of feminism and your impulse to question societal norms?

Carmen Winant: I love that question. In so many ways–once again, I’m sorry to be a broken record–but I didn’t recognize it at the time. I understood even from the time that I was very young that my mother had had a really big life and had participated in a moment in history–both my parents. A moment in history that was transitional and profound, and that they were members of the New Left and were counterculturalists.

Later, after that project, my mom road-tripped or hitchhiked across the country multiple times. There are lots of different ways to be a hippie. There are more drugged-out hippies, or free-love hippies, or back-to-the-land hippies. And not to be too reductive, but my parents were really politically engaged hippies.

And so you just get a sense from the stories that they tell and the way that they relate to politics or their community. I know I’m speaking generally, but it’s even before you can identify it. And so I always really just admired that and wanted it for myself.

And I remember once, as a young person–a preteen–I found my mom’s diary from when she was 18 or 19 years old, and I was reading it. I actually remember, the first place I went was my birthday–and so you can only center yourself. I was reading it and I was like, wow, this is so amazing.

And then I told my mom, “Oh, I found your diary,” and I was reading it, and she was so horrified and felt so violated. But it didn’t even occur to me. I was just like–I want purchase on this life, you know?

That project in particular, but other projects too, like My Birth–have been a way for me to… it’s sort of concentric circles here.

In the innermost circle, to think about my relationship to my mother, as profound and complicated and intimate and interlocking in so many ways. And then the next concentric circle is thinking about the mother-daughter relationship, and she and I are surrogates in that project, although it’s not necessarily about us.

And then a wider concentric circle–this is the most overreaching between projects–is thinking about generational divides politically. What do we inherit from the feminists who came before us, or our mother’s generation? How do we negotiate with that inheritance?

And so my mom in that regard is herself in my work. She’s not just a metaphor–she’s her subjective person. And at the same time, the broader you go, she does begin to act as a symbol, not just for her generation, but the space between our generations.

I’m still working that out. I want to tread carefully because she’s a real person. I don’t want to do the same thing I did with the diary, over and over, as an adult.

Lydia McNiff: Your project The Last Safe Abortion, which you created in 2023, leading to your artist book in 2024, feels incredibly urgent in today’s political climate. With growing threats to reproductive rights, how do you see the significance of this work evolving? Has its meaning deepened for you as the political landscape has shifted?

Carmen Winant: I started working on that project before even the Dobbs leak in 2021–so I started working on it in late 2020. Talk about moving at the speed of life. It was just relentless. It was so relentlessly in the present. I’ve never had a project like that. I talked about this a little bit in the Mia talk, where the clinics were shuttering between visits or between emails. People were really despairing–you know, people in this work.

As I talk about also in that talk, feminist spaces–I really believe this–are necessarily joyful spaces. They’re spaces where we’re inventing how we want the world to be and caring for one another. And so the fact that they continue to do that, and they’re getting doxxed, and they’re having to walk through metal detectors every day, and they’re still going to work…It was really the sort of whiplash that, in both directions, was disorienting and incredibly inspiring.

When I started the project, it sort of moved in the opposite direction–where I live in Ohio, things were looking really bad. We had the Heartbeat Bill, I think for six or eight weeks. And then we had a referendum–that was the work of so much organizing–that people voted to… Sorry, I’m speaking about this in clunky terms, but we basically concretized in our state constitution that we now have abortion care, accessible for up to 22 weeks.

So actually, we had a very positive outcome, all things being told, in Ohio–also as I was working on the project. So it was moving in so many different directions. It felt really important to keep going, but also like the stakes felt really high. I was working with real people who were doing this real work, and I didn’t want to fail them or misrepresent them. They were trusting me. They didn’t really know what the project was going to be. There was a lot of mutual trust.

To the other part of your question–now as I look at that project–I think a couple things. First of all, and this is something that a number of abortion care workers told me in front of the work: this is no longer really what abortion looks like. Sixty-plus percent of women and pregnant people who are having abortions are having pill abortions at home.

So in what ways is this project already anachronistic? What are the terms of representation now around abortion care and abortion access? I’m sorry–this is my first time talking about this out loud,so I’m a little bit disorganized–but now, with the assault on trans people and trans minors, I just feel… it’s not the same thing, but it sort of is the same thing.

I feel like that project is continuing to shift for me. And this happens sometimes, even after a project is essentially finished. It’s sort of like returning to it. Certainly, this has been the case with My Birth and being like, “This part was really imperfect,” or “I’m thinking about this part differently now.”

To your earlier question–how can I build or continue this movement through this work, even from the imperfect parts? So it’s still very emotional work for me to think about and to understand, relative to the ways in which bodily autonomy, agency, dignity are being controlled–relative to questions of gendered power and oppression.

And it’s painful. Even the title of that work came from a number of abortion people–it first came from the director of one clinic in Cleveland, who said, “We will provide the last safe abortion in Ohio.” Then I heard versions of that same exact–almost verbatim–sentence when I visited clinics in Illinois, and at that point, in Kentucky (now they’re closed), and in Indiana (those are closed too). I just felt–what could capture the sentiment better?

It’s so resolute, but it’s also so elegiac. It was sort of a foregone conclusion: that they will be there until the end–but there will be an end. So I feel like there have been certain victories, but there’s been a lot of defeats.

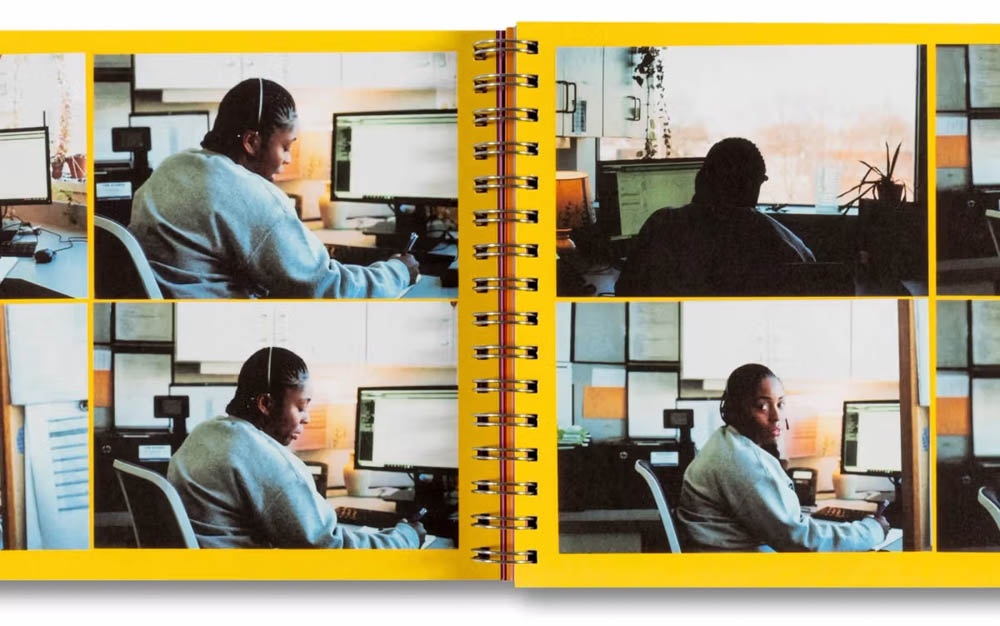

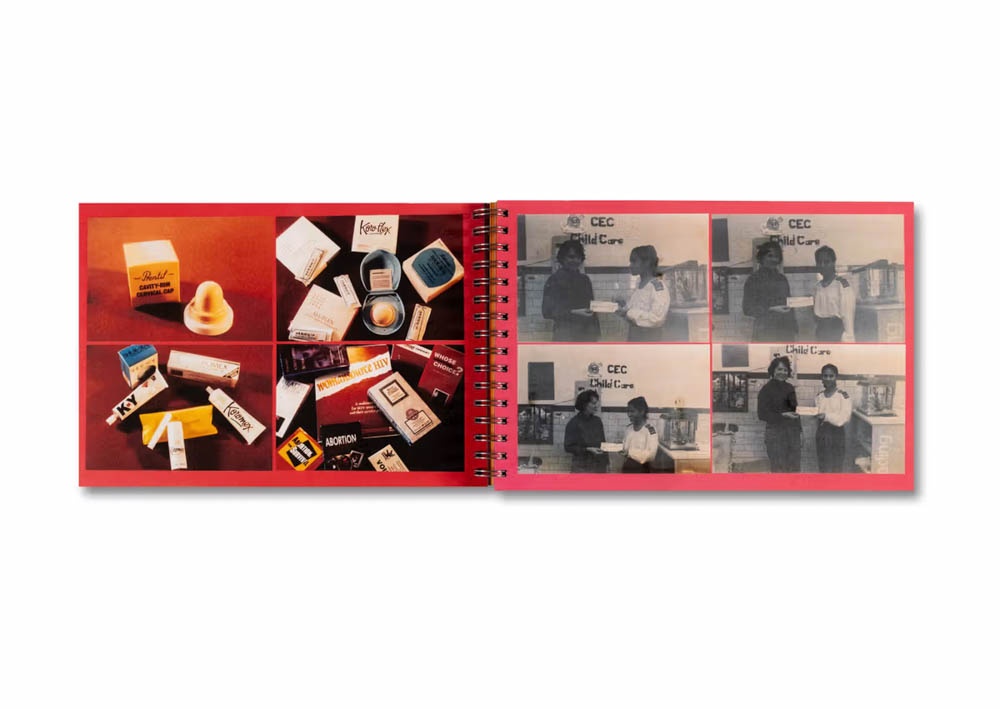

Lydia McNiff: Speaking about that same body of work–the majority of the photographs in The Last Safe Abortion center on unsensational, often banal moments of abortion care: women answering the phone, training sessions waiting rooms. Why are these ordinary and often unseen moments so essential to represent?

Carmen Winant: My favorite kinds of pictures are of women answering the phone. That was kind of a bridge from the Domestic Violence Project that I mentioned, which directly preceded it. There were also many pictures of women answering the hotline there. And I’ve talked about this a little bit, but it really strikes me as like the quintessential feminist picture.

It’s like nothing and everything is happening. What could be less photographic than taking a picture of this most menial and quotidian of tasks? But the charge inside of it, of course, is a life-saving one–and we’re aware of that in both of those projects.

To your earlier question, I didn’t go into the archives thinking, “Okay, these are the kinds of pictures I’m going to look for.” I really hope it doesn’t sound hokey, but I try to let the archives guide me. And that’s not the only kind of picture that’s in the archive. I’m using the “archive” generally to describe the abortion clinics’ photographs, but also some institutional archives where clinics had donated their pictures.

There are a number of pictures in every archive of the cops, and confrontations with the cops, or surveillance pictures they’re making from the inside–of people lurking on the outside through the blinds. There tend to be a lot of photographs of the buildings being constructed. There are these certain kinds of categories, however intentional or not–and many of them are kind of agitated. I really just found myself steering around those pictures. I couldn’t articulate why initially. And of course now, retrospectively, I’m like, oh yes–as you said–those are the sensational pictures.

When you Google “abortion,” or when it comes up in the news, it’s so sensational, it’s so agitated, it’s so violent–whether it’s a so-called aborted fetus or a clinic being firebombed, or Operation Rescue agitators being pulled away by the cops.

But that’s not what it is in those photographs, which is the space of care. It was not hard to find–the lion’s share of pictures in the archives were of that–because that’s their daily reality.

They’re taking pictures of each other answering the phone, cleaning medical equipment, even their staff birthday parties, or hanging out with each other in the park, or Bring Your Daughter to Work Day, which I don’t think exists anymore, but did when I was a kid in the ‘90s.

I was just so attracted to those photographs. They felt so recognizable to me–as somebody who has never worked in these clinics, but has gotten a pap smear every year from when I was a teenager, has gotten an abortion, has volunteered in community health clinics. I just felt this kind of pang of, wow, I don’t know that have I ever actually seen this represented. It was so tender and so regular.

It was all sort of in your question already, but to me, I love the quiet politics of that–as a way to directly counter, with a visual strategy, the hyper-sensationalist strategies used by the conservative right. I think it’s one reason, too, that no one ever came at the work.

Particularly when we showed it in Minneapolis–and actually it just came down from being shown in Nebraska, after the Whitney–at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, which is a pretty red state. There’s always a worry: is someone going to try to destroy the work, or attack the work, or even protest the work?

That hasn’t happened in any of the places it’s been shown. And again, two out of the three of them have been in the Midwest. I think in part–this is my own hypothesis–but it’s because there’s nothing to hang on to. There’s nothing to object to.

It’s just care. This is what care looks like, however basic that is to represent. And I think that has given me a political edge in terms of being able to put the work in public.

Lydia McNiff: These answers are wonderful–thank you. I have just two more questions. How has becoming a mother influenced your artistic identity and your understanding of feminism?

Carmen Winant: I was deeply rooted in this subject when I was pregnant with my second child. My kids were born pretty close together–22 months apart–and I went very late with both of them. They had to induce both at 42 weeks. I remember walking, right before they induced my second one–both of my kids were big, really big babies–and I was walking back and forth on my street trying to shake things up.

I’ve since moved to a different part of the city, but my neighbor at the time was the artist Anne Hamilton. She’s a really well-known artist from Columbus and was my former colleague at OSU. She’s now retired, but she lived a few doors down and has a son who is now in his 30s. I remember she came outside and we were talking–I’m paraphrasing here–but she said something like, “Just try to remember Carmen, it’s all part of the project.”

Meaning, try not to put your kids at odds or in competition with your art making–try to understand them in relation to each other.

This is of course, really hard to do. It’s one thing to talk about that romantically. But when I’m on a deadline and my kid has to be picked up early from school because he’s pooped his pants, or has a fever, or his tummy hurts–it’s hard to be like, “This is all part of the project.” I was already thinking along those lines but I always think back to that conversation and really look at how I can take those words at face value.

For instance, I’ve always had my studio at home. When my kids were little, I could put them down for a nap and go into the studio. The physical proximity was important to me–for that kind of conceptual bleed. In my case, too, I think this was really a strategy of survival more than anything else: taking my experiences and struggles in motherhood and emptying them into the work. Using the work as a place to process them and center them, and to insist–even for myself–that they were serious and meaningful as the subjects of creative and intellectual inquiry.

For me, it’s been everything. I know plenty of mother-artists for whom that’s not the case, so it’s certainly not a prescription.

I was already interested in–as we’ve talked about–what does it mean to be a feminist? And what is the relationship between being a feminist and attending to a certain politics of care? Even before becoming a mother, care work was central to my understanding of my feminist ethics. So when I became a mother, it only augmented and augmented–and, in some ways, transformed.

I just want to be careful not to sound prescriptive. It was, frankly, a way for me to survive my own circumstances–to understand it all as part of the project.

Lydia McNiff: My final question to wrap everything up: What has been the most valuable lesson you’ve learned throughout your photography career, and what advice would you offer to an aspiring photographer like myself who is just starting out?

Carmen Winant: This is sort of an obvious lesson, but it’s one that I think is really helpful to keep reiterating–and it dovetails with my last response.

When I was in undergrad, I had as my professor, Cathy Opie, who’s a very well known photographer and just recently retired only two years ago. She was a very dedicated teacher. I remember how, in subtle but also overt ways, she gave us the confidence to take what was happening in our lives seriously.

This is where it dovetails with this idea of centering motherhood–when I later wondered, Is this serious enough? I remember I had a classmate who was in a sorority, and Cathy said, “That’s interesting. Make photos of that.”

I was an athlete in undergrad–that’s what brought me to UCLA–I was a runner. And I felt like, This is so unserious. I’m just a jock. It was a very conceptual program, and I didn’t want anyone to know. I felt like no one’s going to take me seriously–that they’re going to think I’m all body and no mind. And Cathy really encouraged me to take the conditions of my life seriously as a subject. And I still wrestle with that.

I think so much of it is a kind of internalized misogyny–that this isn’t a real subject. But I still hear her voice echoing in my head when I think about how, Yes, this is substantial. This isn’t small or minor or unserious if it is happening to you. You want to center it in your work.

Being an artist and moving through this sounds, once again, kind of obvious advice, but community. Depending on where you live, that can mean different things. This is something I really liked about living in the Midwest is that it hasn’t felt like there’s a scarcity mentality around it. You know–where everyone has to guard their thing, like it’s a zero-sum game and we’re all in competition with each other.

I’ve lived in New York, LA and San Francisco. There are great things about living in those cities, but they were really saturated with artists. And it felt like it was really hard to find a supportive community. But I was younger and I think maybe no matter where I was, I wouldn’t have known how to do that.

I still remember a story from a former studio mate. She told me she used to share a studio with another painter, and she would come in after the other painter had studio visits to find that her work was turned around so it was facing the wall–this way, the curator, dealer, or whoever was coming in wouldn’t even see her work.

I remember thinking, Is it that poisonous?

Any opportunities that I’ve had have come from friendships and really invested, mutually engaged relationships that are not transactional. What does it take to build those kinds of relationships first–and in service of each other–without thinking, What am I going to get from this? That will never sustain, that will never yield.

I insist on this over and over again to my students. There’s lots of ways to develop community. But it’s important to be thinking about, what does that investment look like? How can it be centered as a priority as you move through your life as an artist?

So I would say the same to you. That’s great advice.

Lydia McNiff (b. 2001, Bloomington, IL; based in Normal, IL) is a photographer currently making work centering women’s health and feminist ideologies. She earned her Associate of Arts degree with a focus in graphic design from Heartland Community College and a Bachelor of Science degree with a focus in photography from Illinois State University. Her work has been exhibited both locally and internationally, including at the McLean County Arts Center, University Galleries at Illinois State University, The Coffeehouse and Deli in Normal, the Springfield Clinic Center for Women’s Health, and PH21 Photography Gallery in Budapest, Hungary.

In 2024, Lydia received the Irving S. and Joan Tick Award for her piece The Pelvic Exam at the University Galleries Student Annual Exhibition. Her series Visceral was also published and recognized that year as a Student Prize Finalist by Lenscratch. Through her work, she seeks to foster dialogue around women’s health, pursue meaningful opportunities within the art world, and engage in collaborative creative practices.

Instagram: @lydiamcniff_photography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026