Photographers on Photographers: Alexander Iglesias in Conversation with Ahndraya Parlato

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today we share the conversation with Alexander Iglesias and Ahndraya Parlato. Thank you to both of the artists.

Photographs tend to give authority to the personal experience of the maker. When you see a photograph, you see a literal point of view constructed by the whims and opinions of the maker who then goes on to select the “best” photograph to share out of the many they took. A photograph is inherently bound to the way a maker sees the world. But who cares about how the maker sees the world? Well actually, a lot of people do. The personal aspect of art lends a power and depth that is hard to quantify.

Ahndraya Parlato’s work highlights this power. Ahndraya’s work is exceptionally personal, she’s discussed the navigation of reality, balancing the real and unreal, the suicide of her mother, the murder of her grandmother, and the way all of this affects how she feels as a mother. The fear and anxiety expressed in her work provides a handhold for a viewer to grab onto and connect with the work in their own way. The more specific something is, the more general it really begins to be. With her new book, TIME TO KILL, Ahndraya discusses the concept of “gendered aging” which is the difference between men and women’s experience of growing older. With this work, she highlights the cultural stigma towards aging women while also showing the catharsis from finally being free from the sexualizing gaze of our culture.

I was extremely excited for the opportunity to write a Photographers on Photographers article for Lenscratch, as I had a legitimate reason to ask Ahndraya a bunch of questions about her new work and process. Ahndraya has a truly amazing mind and has something to teach everybody.

Ahndraya Parlato has published three books: Who Is Changed and Who Is Dead, (Mack Books, 2021), A Spectacle and Nothing Strange, (Kehrer Verlag, 2016), and East of the Sun, West of the Moon, (a collaboration with Gregory Halpern, Études Books, 2014). Additionally, she has contributed texts to Double feature (St. Lucy Books, 2025), Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Shoot (Aperture, 2021), and The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014).

Ahndraya has exhibited work at: Spazio Labo, in Bologna, Italy, Silver Eye Center for Photography, Pittsburgh, PA, The Aperture Foundation, New York, NY, and The Swiss Institute, Milan, Italy. She has been awarded residencies at Light Work and The Visual Studies Workshop, and grants from Light Work, the New York Foundation for the Arts and is a 2024 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow.

Ahndraya’s most recent project, TIME TO KILL is forthcoming from Mack Books in 2026. She has taught in the Bard College and Cornell Image Text MFA programs and is currently an Assistant Professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Instagram: @draya_parlato/#

Firstly, I’d like to congratulate you on TIME TO KILL, forthcoming from Mack book. I cannot wait to see the culmination of your work; I’ve been so excited about this project since I printed some contact sheets for you. The project seems to me like a marked shift from your prior work. I have thought of your last two books as a guided journey for the viewer, whereas the new book seems more conversational, even confrontational. Can you speak a bit on this?

Thanks, Alex! I’m excited to see the finished book too. It will be released in the US in January of 2026.

Honestly, I don’t see any of my projects as guides. I’ve always been more concerned with asking people things (which is conversational) rather than in telling them things. That said, I do think that as I get older, I’m increasingly drawn to asking harder, less direct questions, which could make it feel more confrontational in some ways. For me, the biggest difference with this project was working with strangers instead of people I know intimately – which is what I’ve done for the past 20 years.

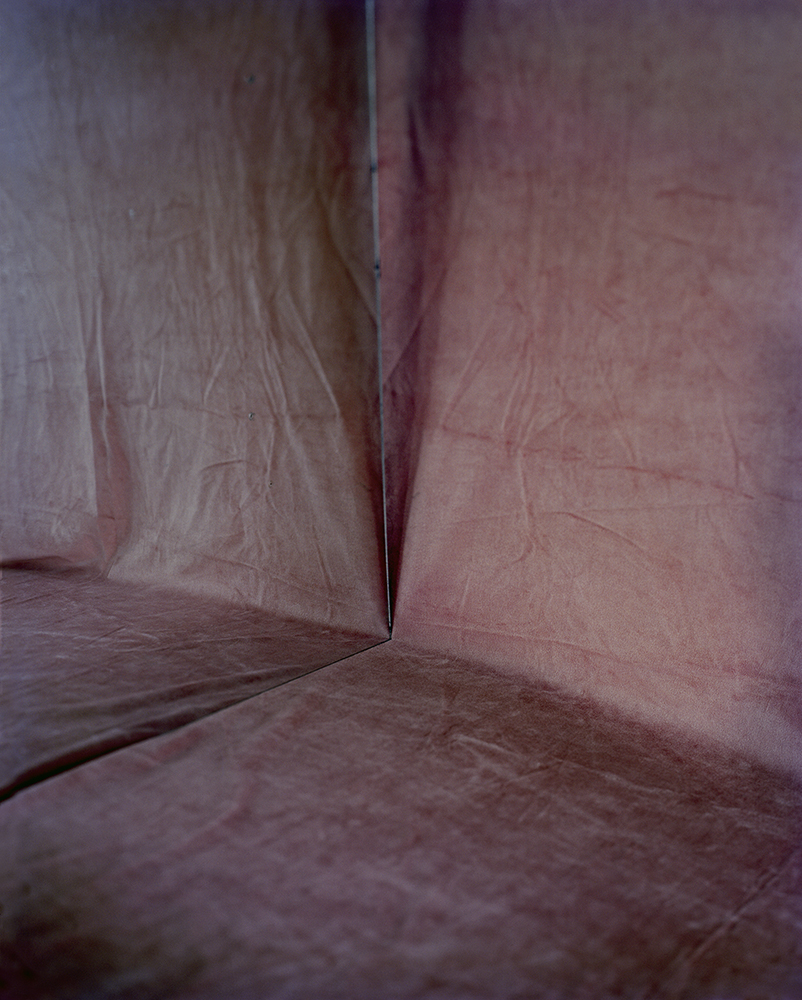

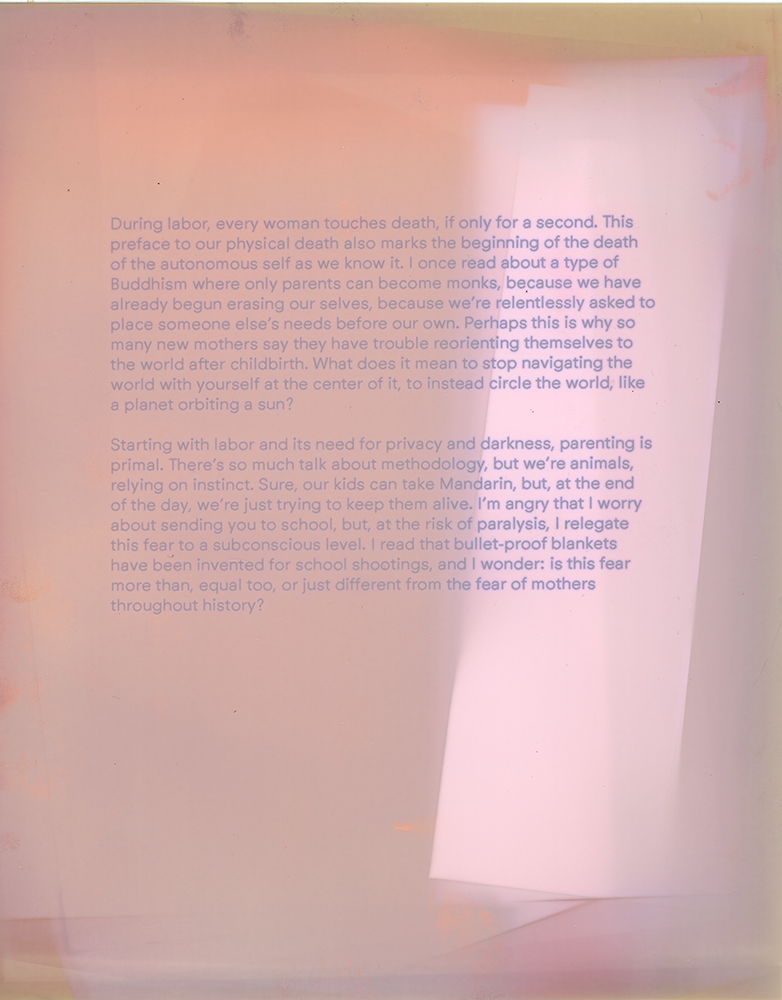

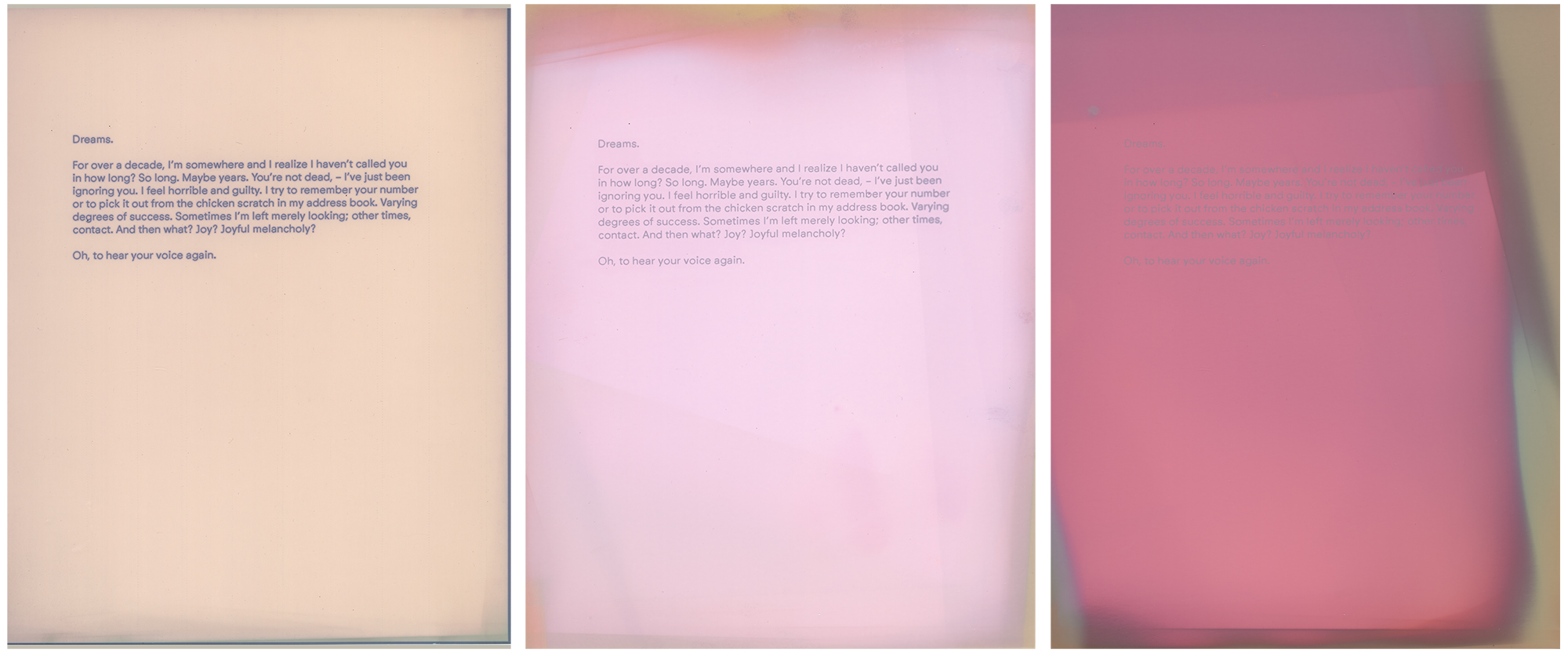

© Ahndraya Parlato, Unfixed Lumen Print, text excerpt from Who Is Changed and Who Is Dead (MACK, 2021)

I want to start by asking about your background in photography. How did you discover it? What about the medium draws you to it? What do you like about it?

I discovered photography in 6th grade through National Geographic and Vogue, both of which I coveted equally. I was drawn to photography because I wanted to make my interior landscape—i.e. the invisible—visible; and while any medium, to some extent, brings the invisible to light, photography, with its direct correlation to the world, allows us a nuanced way to navigate the complexities and contradictions of reality versus representation. It’s the perfect medium to explore the tensions and boundaries between what’s real and imagined, what’s factual and fictional.

I love making images. It never fails to surprise me how beautiful the world looks on my ground glass—even when it’s upside down and reversed. I also tend to be somewhat of a solution-oriented person, and creating a good picture is essentially the process of solving many problems at once, so it suits me in that way as well.

I listened to the PhotoWork podcast you had done with Sasha Wolf to research for the interview and there were many things you said that interested me and that I had some questions. You had mentioned that despite loving photography, you can sometimes become bored with photographs (particularly ones of a soulless nature) which led you to work with multiple visual strategies and also text. You went on to say that the image-text format is a different medium from photography for you. Can you speak more about this distinction and your view of image-text?

Simply put, combining two things does something different than a single thing could do on its own. In a traditional photographic project, one essentially translates what one sees into words, feelings, and, ultimately, meaning. But when you add text to a photographic project, one’s process changes. Now, you’re translating both the pictures into words and feelings, and the words into images and feelings—and, again, into meaning. But what happens if the words and images make you feel different things? What if they push and pull, or extend each other in unexpected ways? The potential to complicate feels much more accessible to me now. With my desire to ask less direct questions and offer less concise answers, this approach has been working for me in ways that images alone didn’t seem capable of.

Photography shares a Venn diagram with all other artistic mediums. Ultimately, it comes down to the labels we use and how we frame the work. I love Charles Ray’s Plank Piece I and II—it’s a performance at its core, and like many performances, we only experience it through a photograph. Yet, it’s technically classified as sculpture, which is so much more interesting to think about than if we to call it a performance or a photograph.

In the podcast, you speak about how the photographs that you instantly love are not usually the best, but it is instead the pictures that have a “slow burn” of enjoyment and that continue to reveal themselves to you that are actually quality photographs. I’m curious how this belief affects your editing, do you select your favorites with the knowledge that they aren’t going to be your keepers, while keeping a pile of images that might be slow burns or might be nothing?

Yes, often the photographs we make and love instantly are the ones that are easiest to love—so they tend to be a bit simpler conceptually or overly aestheticized. Like many photographers, at first, I often include these images. But I work slowly enough that hopefully by the time I’m wrapping a project up, the low-hanging fruit has been culled. So, when editing, I select the images that I think are successful individually and also working in a larger sense, but I keep re-assessing, as the project grows, whether or not they’re still serving it.

I’m not sure if they’re “slow burns” or not, but there are usually a handful of images I know that I want to use at some point, even if they’re not right for my current project – that I keep in mind for future use. For example, this new project includes an image I made during my sophomore year of undergrad!

As you mentioned previously, you started working with strangers for the first time with this project. When you’ve spoken about this process, you’ve mentioned that you tend to learn a lot about your subjects’ personal life while photographing them. I’ve often compared the experience of photographing strangers to that of a bartender; people just want to tell you everything about themselves and admit to things they can’t with others. Does their story work its way into your writing or photographs in any explicit way? Did working closely with strangers make the work collaborative, maybe changing the way you make pictures of them or altering your editing decisions?

It is true that the women I’ve been photographing have generally been open and vulnerable with me. I see this as a result both of them having reached out to me and to my own openness: I show them my prior work and talk candidly about my mother’s suicide, my grandmother’s murder, and my own anxieties. In a way, my vulnerability invites theirs. Some of their stories have made it into my writing, but only when they relate to the themes I’m already looking at. The project is about my own fears and fantasies, not anyone else’s life story.

The images, however, are somewhat collaborative. If I can sense a way a woman wants to be photographed, I’ll lean into it—though it may take me a moment. One of the women I photographed told me early into our session that she had no problem being photographed nude and that she had undergone a double mastectomy. At the time, I was uncertain about photographing women nude, given the history of nude women in art. But I was also curious, given the lack of images of women in this age group. So, while I understood that she wanted to be photographed nude, in that moment, I didn’t feel mentally equipped to make those images. A year later, I called her, and we ended up making them. In terms of the specific images of the women that I choose, I’m not intentionally choosing them with any conscious thought about the things that they’ve said to me or our experiences together – but of course that may factor in in unconscious ways.

Can you talk a bit about what plants and flowers mean to you? You have this encyclopedic knowledge of plants that I remember amazed me in my sophomore year. In Who is Changed and Who is Dead, you mention that your grandmother and you bonded through your mutual love of flora. You seemingly love to photograph plants; they are throughout your photobooks. I’m just curious why you keep coming back to them beyond their beauty and if there is a deeper reason.

Haha, what a sweet question! I have both a sweet and an unsweet answer. The sweet answer is that I genuinely love flora (and fauna). They’re probably the primary things that remind me how wondrous the world is. The unsweet answer is that I often feel stymied by the fact that words are so inadequate when it comes to expressing our needs and feelings, which might also be why I make pictures. One result of that is that I try to use words with as much precision as I can. There’s a power in knowledge, and part of me enjoys knowing the names of things. The narratives I tell myself about why or how something is happening literally shape how I feel or what I think. And there’s a certain way that accuracy plays into all of this – somehow saying “the yarrow” in your picture feels more fulfilling than just calling them “the flowers.”

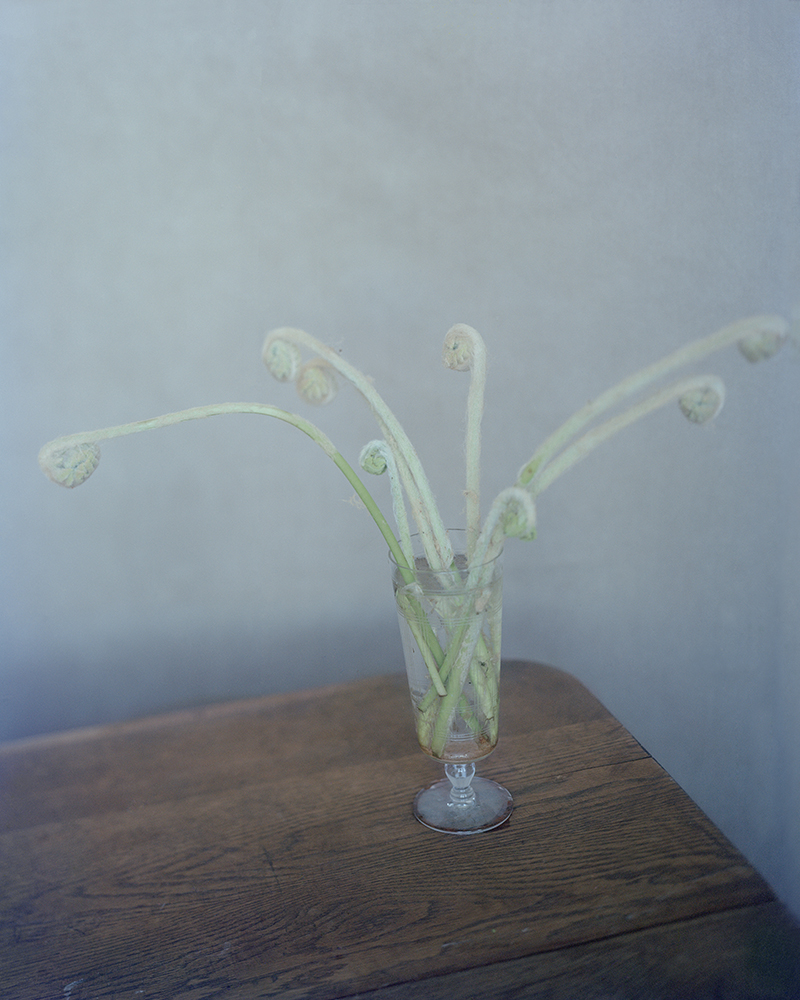

I am curious about your still life process. How do you come to select the objects to photograph, decide to pose them, then come to the titles you have given them (i.e. A picture of plants in a glass cup of water named “I ain’t no goddamn son of a bitch”)? In Who Is Changed and Who Is Dead The objects were very purposefully selected to reference art history with objects referencing death, dying, etc. Does the still life process start with research for you? What is it about the still life that keeps your attention?

The subject matter that I choose is generally selected for its conceptual correlation to the project, although not always from a research perspective – sometimes I’m just using my own emotional logic – the poses are intuitive – and then meticulously workshopped and sometimes re-shot if necessary. In general, I gravitate towards multiple subjects or strategies to speak to the themes at hand, because it so clearly complicates matters, rather then, using a single subject would. Still lives evoke a different response than figurative images do. I’ve always loved Collier Schorr’s text from the back of their book, Blumen, “Still lives are simply endnotes. Pointing towards something too theatrical to be directed with human flesh.”

Historically, I hated titling photographs; all my images were just, Untitled from the series they were part of. But for this most recent project, it was important to me that the women I photograph have their names associated with their images—and not be Untitled – which didn’t feel right. That led me to understand that all the images from this series, (TIME TO KILL), needed titles for cohesion. And I’ve been loving it! A lot of my titles are phrases that occur to me while running or that I encounter in music or books. I keep an ongoing list of these phrases and then pair them later to photographs.

In general, my thoughts on the relationship between text and images is that they should expand and complicate each other, not simply explain or mirror one another. So, I knew I wanted the titles to be metaphoric. I don’t want to tell anyone what they already know. For example, what does “Baby Ferns” really do for anyone? “I ain’t no goddamn son of a bitch” is a line from a Misfits song, and I love the tension it creates when paired with the sweet, tender ferns. I was thinking about how women are culturally conditioned to be sweet, and how we’re often judged harshly for being assertive or bitchy.

© Ahndraya Parlato, Unfixed Lumen Prints, text excerpt from Who Is Changed and Who Is Dead (MACK, 2021)

When Ahndraya exhibits this series, her texts are shown as lumen prints. Some prints are fixed – retaining visibility, while others are unfixed, causing the words to “die” over the course of the exhibition. Based on the paper stock and proximity to light, each print dies differently and at a different speed.

You have said that with every project you want to push yourself and do something that is new to you. In Who is Changed and Who is Dead, you added text in your approach, now with TIME TO KILL are adding pictures of strangers and the style of writing sounds like it has shifted. Do you feel uncomfortable stepping out into these unfamiliar approaches? If so, is the discomfort you feel important to the work itself? What method or skill is next on your agenda?

It might be uncomfortable—but I like it. Discomfort keeps me engaged with the medium. I have this theory that artists are generally interested in the same themes throughout their entire lives, and the goal is finding ways to continually trick yourself into thinking your themes have shifted or to explore them in new and more compelling ways. For me, that discomfort—which I might just call a learning curve—is crucial. It keeps me actively engaged in the making process and in seeing my set of themes in new ways.

I don’t have an agenda per se; so far, everything has developed organically. With the last project, it just happened that the writing needed to be done by me. With this one, it ended up that most of the subjects needed to be strangers—those were things I discovered during the act of making. So, I have no idea what’s next. But I love objects, and I’m currently working on a show of TIME TO KILL for the George Eastman Museum; so right now, I’m having fun thinking about what kinds of three-dimensional works can be made in dialogue with these texts and images, and how the text itself can be transformed into objects.

I’d love to know more about how you write and edit. Has your process for writing changed from your last book, Who is Changed and Who is Dead? to the forthcoming TIME TO KILL? It sounds like the form of the text in your books is changing, the last book had the tone of a memoir but now it seems you are maybe stepping towards fiction.

Embarrassingly, I seem to only write in fragments that can be associatively strung together. So, my process generally involves accumulating these fragments, workshopping them stylistically, and sequencing them. Once that’s done, I step back and look at the whole piece, paying attention to where bridges need to be built between certain ideas or where redundancies need to be cut.

The style of my new essay is like the piece in my last book, with the addition of a series of letters to a vampire, whom I’ve been using as a metaphor for immortality and never aging. That’s the one fictional element. However, aside from the slightly cheekier tone of the letters themselves, the content could easily function within the other section.

To end, I just want to ask about your inspirations. Who are the artists that are most influential to you? I’d also love to know what mentors you’ve found most important to you and your work. You’ve had the privilege of being around so many amazing artists, I’m sure it isn’t easy to point a few out but I’d appreciate the attempt.

I draw most of my inspiration from films and books. Among filmmakers, I admire Krzysztof Kieslowski, Agnès Varda, John Cassavetes, and Andrei Tarkovsky. As for authors, I’m drawn to Rachel Cusk, Samantha Hunt, Anakana Schofield, and Sally Rooney. That said, my two most important mentors were Barbara Ess and Larry Sultan. Barbara taught me that a photograph could convey meaning beyond what was literally within the frame, and that I shouldn’t pander to aesthetics. Larry showed me that a successful photograph doesn’t have to sacrifice content for aesthetics—or vice versa—and encouraged me to embrace my sense of humor.

Alexander Iglesias was born in Florida in 2001. They moved around the United States several times before settling in Chattanooga, Tennessee at the age of 13. Alexander started making photographs of their friends and their own experience of the American south. Alexander went to the Rochester Institute of Technology, graduating with their BFA in 2024. They have been recognized as a noteworthy emerging artist, winning the 2024 Urbanautica Institute Award, being included in the 2024 Lensculture Talent Award, the Context 2025 group exhibition at Filter Photo, accepted into Atelier Smedsby, listed in the 39th edition of the American Photography Archive, and more.

Alexander’s practice is personal in approach and utilizes photographs and text the way one would in a diary. Their work is characterized by its transparency, yet is shaped by personal experience and baggage. Their long-term project and graduation exhibition, I Love It Here, I Hate It Here, exemplifies this approach with Alexander’s depiction of growing up in Tennessee.

Alexander now lives and works in Oakland, California.

Instagram: @alexander_d_i/

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026