Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala Miller

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Cléo Richez and Shala Miller are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

One of the first moments I met Shala Miller was when I worked for them one summer at my grad school. I was playing Blood Orange’s NPR Tiny Desk while scanning some film, they opened their office door to ask me what that sound was, and we started talking about music. And then, Sex & the City. And then, being film bros. And then, I can’t remember.

One of the first moments I also met Shala was through looking at their website and finding out that their artist statement was a video of their mother telling them how to help with the Thanksgiving cooking.

One of the first moments I also also met Shala was through hearing them sing in their office on their lunch break.

One of the first moments I also also also met Shala was through going to a screening of their early films and tearing up.

One of the first moments I also also also also met Shala was at Peck’s on Myrtle over a strawberry matcha, and this is the conversation that resulted from it.

Shala (pronounced shay-luhh) Miller, also know as Freddie June when they sing, was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio by two southerners named Al and Ruby. At around the age of 10 or 11, Miller discovered quietude, the kind you’re sort of pushed into, and then was fooled into thinking that this is where they should stay put. Since then, Miller has been trying to find their way out, and find their way into an understanding of themself and their history, using photography, video, film, writing and singing as an aid in this process. They love to bake and consider dessert their religion.

Instagram: @freddie.june

CR: Is there a song that you listen to on repeat? Or a musical artist you come back to a lot?

SM: Not to sound like an asshole… but there is a Philip Glass song that I love from The Hours soundtrack.

CR: I love Philip Glass!

SM: Okay, yes, there’s a particular moment in that song that I repeat over and over again- and Going Home by Alice Coltrane! There’s something that happens in the melody. I’m also working on a new music piece for a choir, so I’ve been trying to learn how to write something for a big group of people.

I love live recordings of jazz vocalists from the 60s and 70s, but especially the 50s. In particular, Sarah Vaughan, Carmen McRae, Betty Carter, and Ella Fitzgerald.

The recording is always different from how they perform it live, and the way that they choose to end a song! The melody takes a shift in such an unexpected way that still feels right and completely different from how it was performed the last time.

There are also some songs that I come back to as storytelling references. For example, The Greatest Performance of My Life. There are so many different renditions of this song. But my favorite one is Shirley Bassey’s.

The Greatest Performance of My Life is basically the song version of Opening Night by John Cassavetes, which is one of my favorite movies.

It’s just her talking about giving the greatest performance of her life and how nobody would have known that as soon as the show ended and the curtains went down, she was crying because of whatever was happening in her real life.

That is kind of like how I am trying to make images like self-portraits, this kind of breaking the fourth wall. She’s talking about this performance while performing. You could argue that this story that she’s created of being this actress and giving this performance is actively happening as she’s sin

CR: How has your relationship to self-portraiture evolved through time?

SM: Well, now it’s a lot more playful. It mostly started out of convenience as a teenager. I was terribly shy. For a long time, I didn’t really know how to talk to people. I didn’t have many friends. So I took pictures of myself and my parents.

Yet at the same time, I really wanted to perform. Self-portraiture began as a place to tap into that performative space.

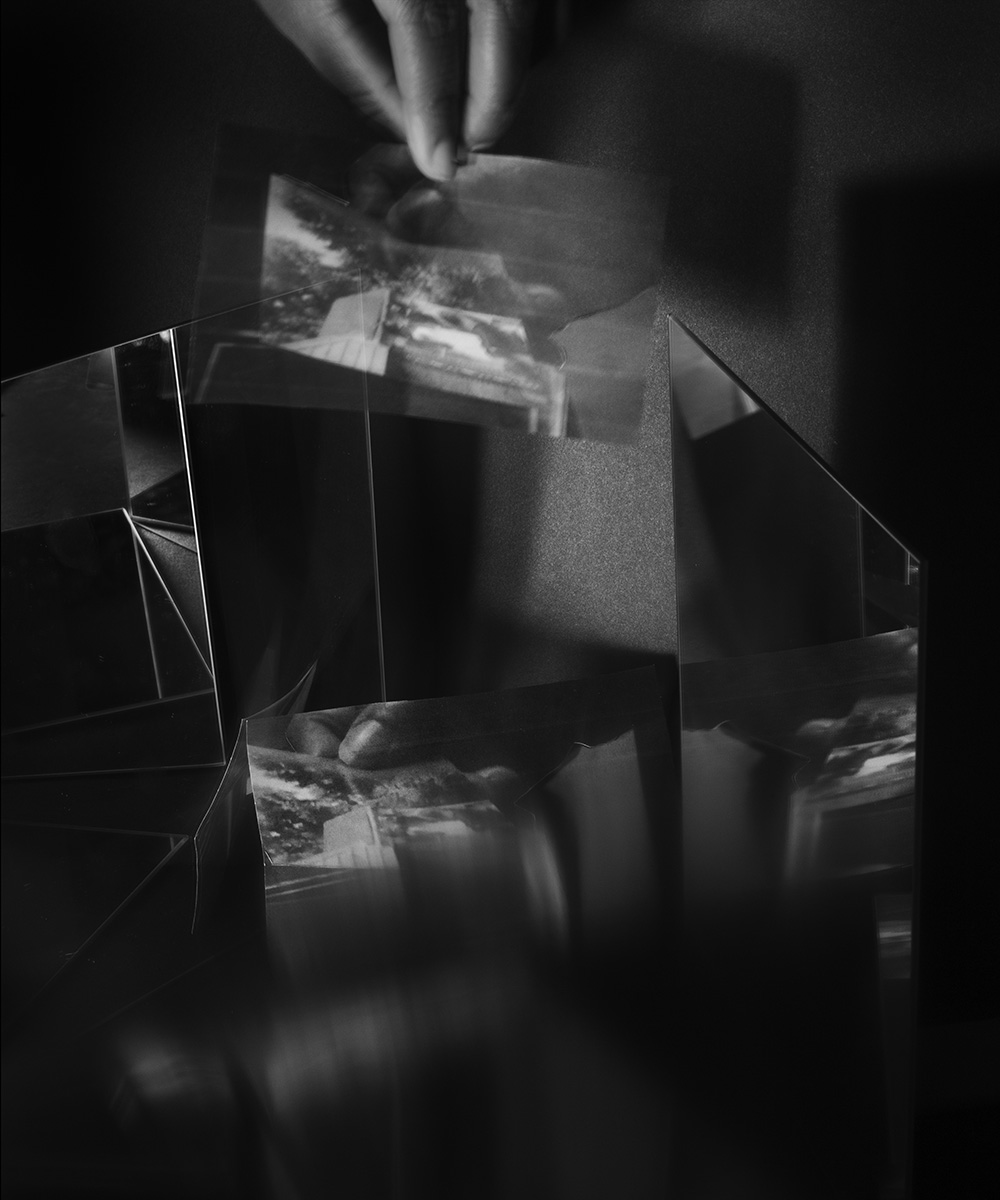

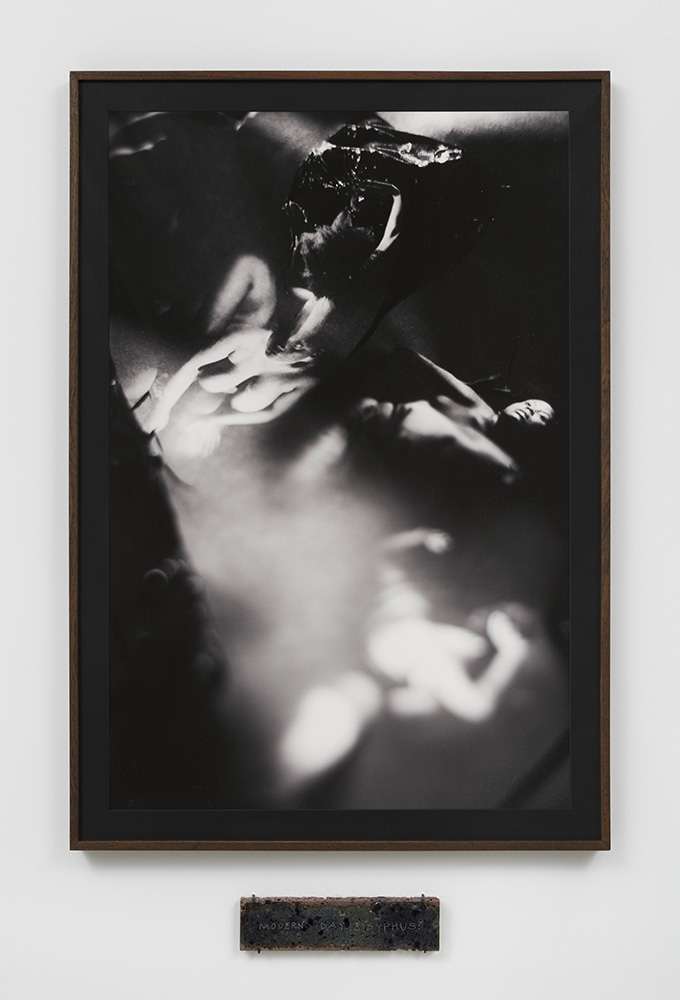

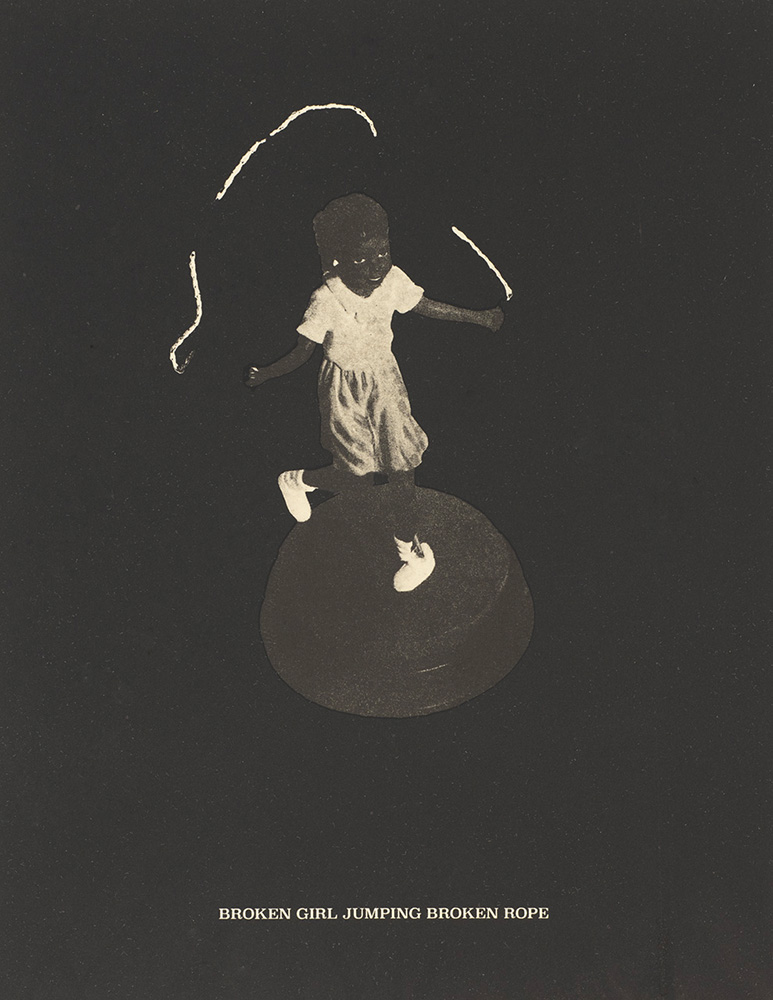

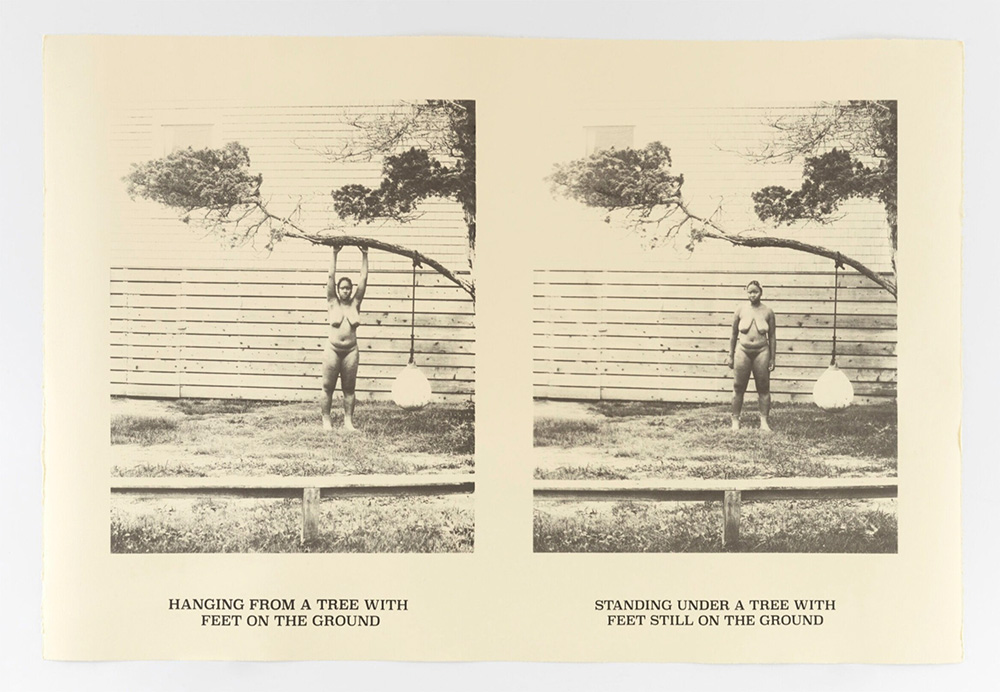

In the past couple of years, it’s taken a new turn where I am trying to stretch the limits of self-portraiture while using performance as an engine to do it.

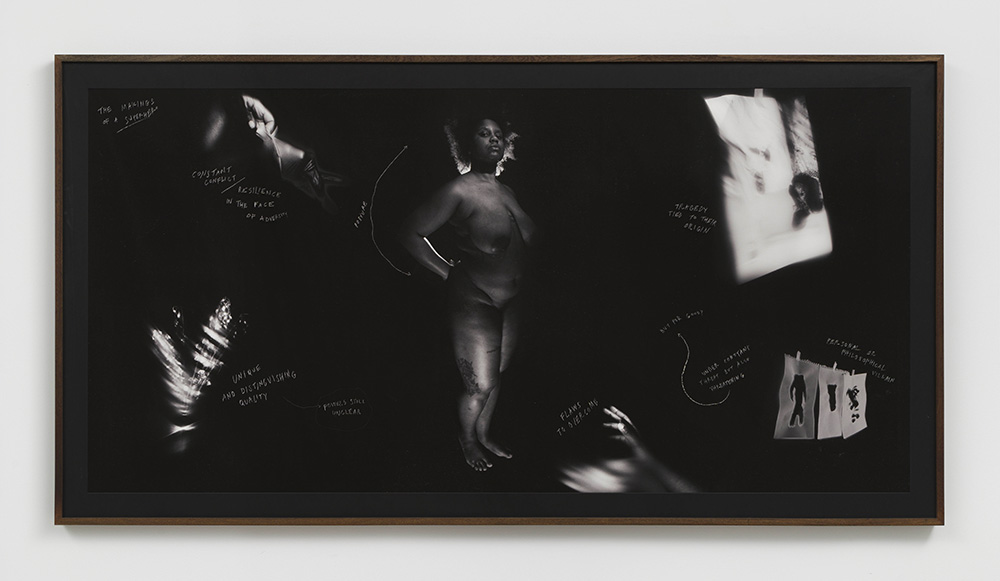

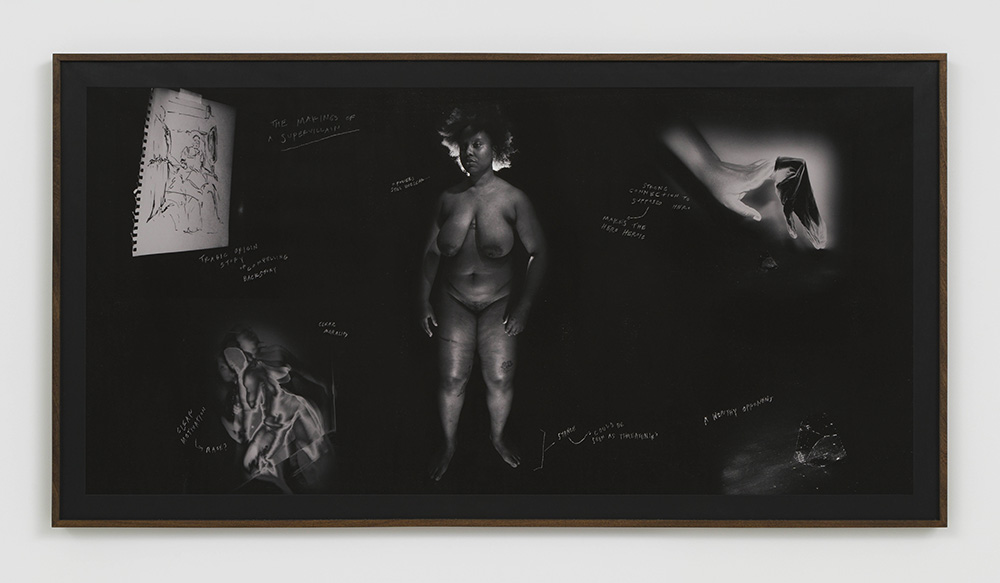

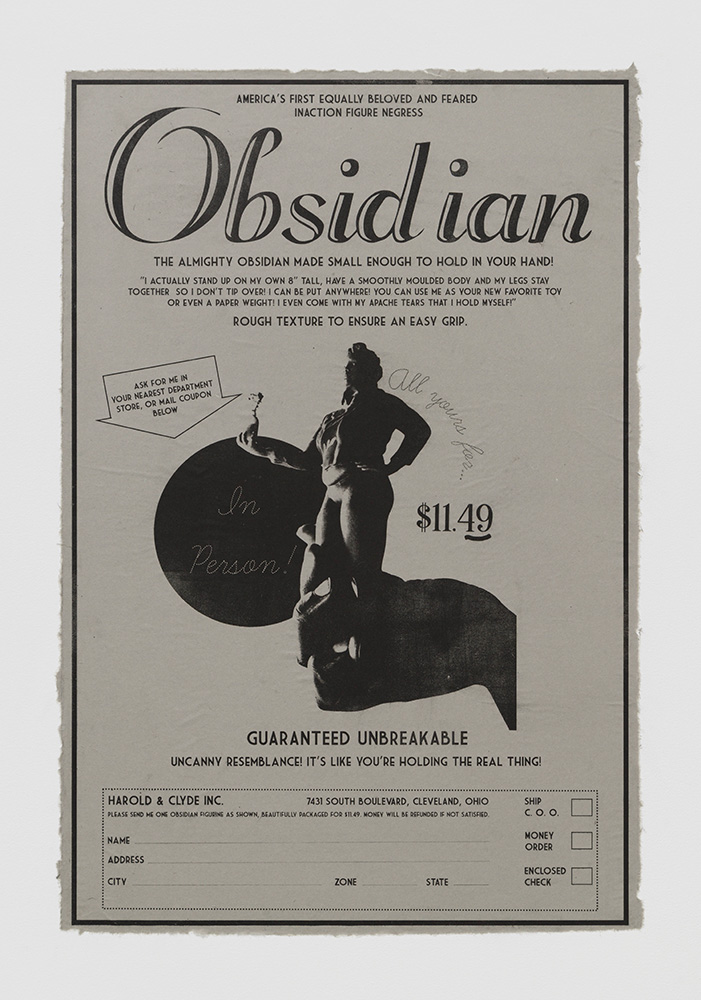

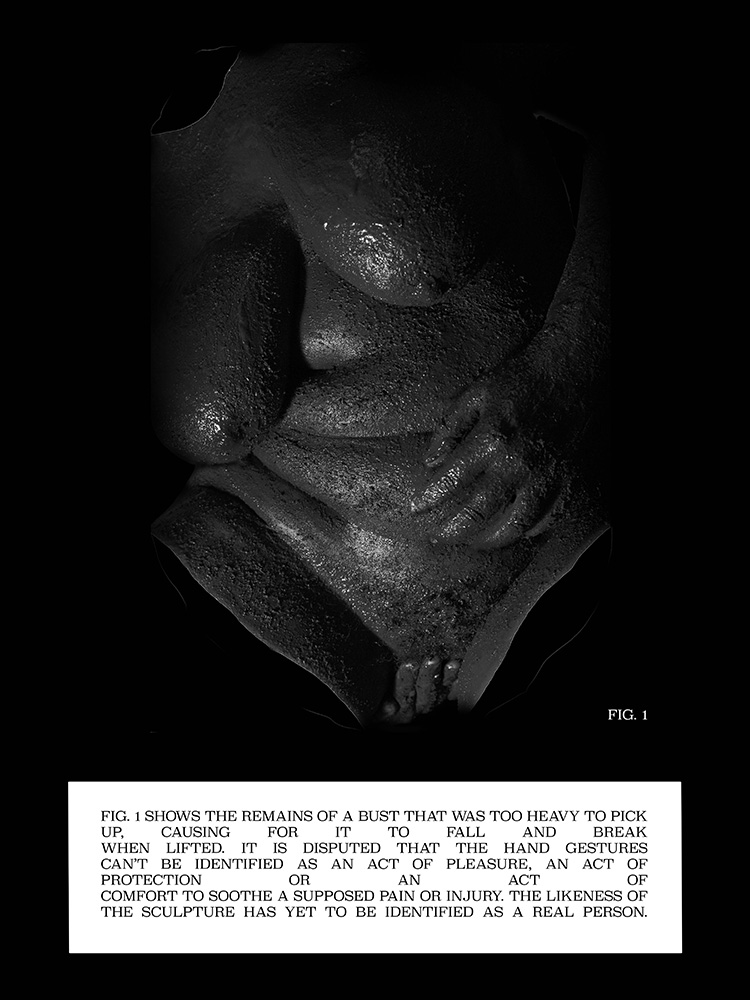

I created this alter ego named Obsidian. It had many different levels of fiction. It was this fictitious art historian who found this archive of this fictional comic artist. And in those comics is this character, Obsidian, and all those characters I’m playing. I’m actively working on it right now because I feel like there are a lot of accessibility issues with the project.

But it’s opened up a new way for me to think about world-building and fiction and how to use that in still photography.

What do you mean by a problem with accessibility?

I think it’s so complicated. The part of it that is successful to me is that I was trying to let people in on this process of mine and what I was moving through, which was self-doubt, questioning, rage, and grief, and those things complicating one another. The success was that it was… complicated.

I have a tendency to over-explain myself because I feel like I need to. A common experience of Black people, especially Black femme-presenting, is feeling as though people are committed to misunderstanding us. That has left an impression on me where I feel so ready to over-explain to prove that I’m smart enough, or whatever it may be.

So I think a lot of that project was trying to prove my own humanity. That was another element of me moving through all those feelings. I hated doing that. I felt like I was doing things in spite of whiteness, and I hate doing things in spite. Yet here I was.

Someone recently told me that they wouldn’t have known that full story if I hadn’t explained it. So I was like, ‘That’s an issue, I don’t like that. People aren’t able to understand’ But then there’s another element of, ‘Maybe they don’t need to. Maybe that person doesn’t need to. Why do I need to work overtime to try to make everybody understand?’.

CR: I remember in a writing class in grad school, I was talking about Édouard Glissant and his whole writing about opacity and how helpful it was for me to navigate my practice at the time. And my friend Andrew was like, ‘You know if they get it, they get it. If they don’t, they don’t. That’s it’. Are you able to have that feeling sometimes of like ‘fuck it’?

SM: I used to, but then I kind of just stopped over the past year. There’s a part of me that deeply respects that kind of attitude and way of moving. Especially as a person of color or a marginalized person of any kind, I think it’s important. Then, at the same time, I do want to understand that it was my choice to make something and to put it out.

CR: You once told me how much you loved Bluets by Maggie Nelson. What is your relationship to that book?

SM: I was changed by it on many different levels. Formally, it’s such a genius book. That way of writing feels radical yet incredibly intimate and, in some moments, quotidian. Sometimes, she is literally just talking about the color blue, and then about the feeling. It’s both simple, complicated, and expansive. I read that book when I first moved to New York. At the time, I was 23 and I was at a moment where I was trying to make sense of myself as a person. It felt like a very particular kind of becoming.

Then, much later, I started giving it to my students in my conceptual practices class. It’s this perfect example of conceptual thinking. Nelson followed a kind of obsession and inquiry she couldn’t get away from. Which made it very unique and beautifully moving.

After reading it, my students tended to trust their ideas, obsessions, and interests more.

CR: Is there a story from your childhood that has influenced your storytelling?

SM: I’ve always been someone who keeps a journal, ever since I was a preteen. I like to return to them as a way to understand my current reality.

Then, the way that I write in my adult years is often through speaking. I usually dictate things first. Let it be for an essay, a script for a video, or something else.

The way that I’m dictating these feelings or stories is influenced by the way my parents would tell stories. Especially my mom. She is so chatty! I remember being 8 or 9, daydreaming so hard about a camp for mothers who talk too much, where they would learn how to be quiet. I remember being so serious about it.

But the way she tells stories is very particular. She starts a sentence and doesn’t finish it, and then comes over here and then there and back to here. It’s sometimes maddening to listen to, but then at the same time, I like this abstract journey she takes me on.

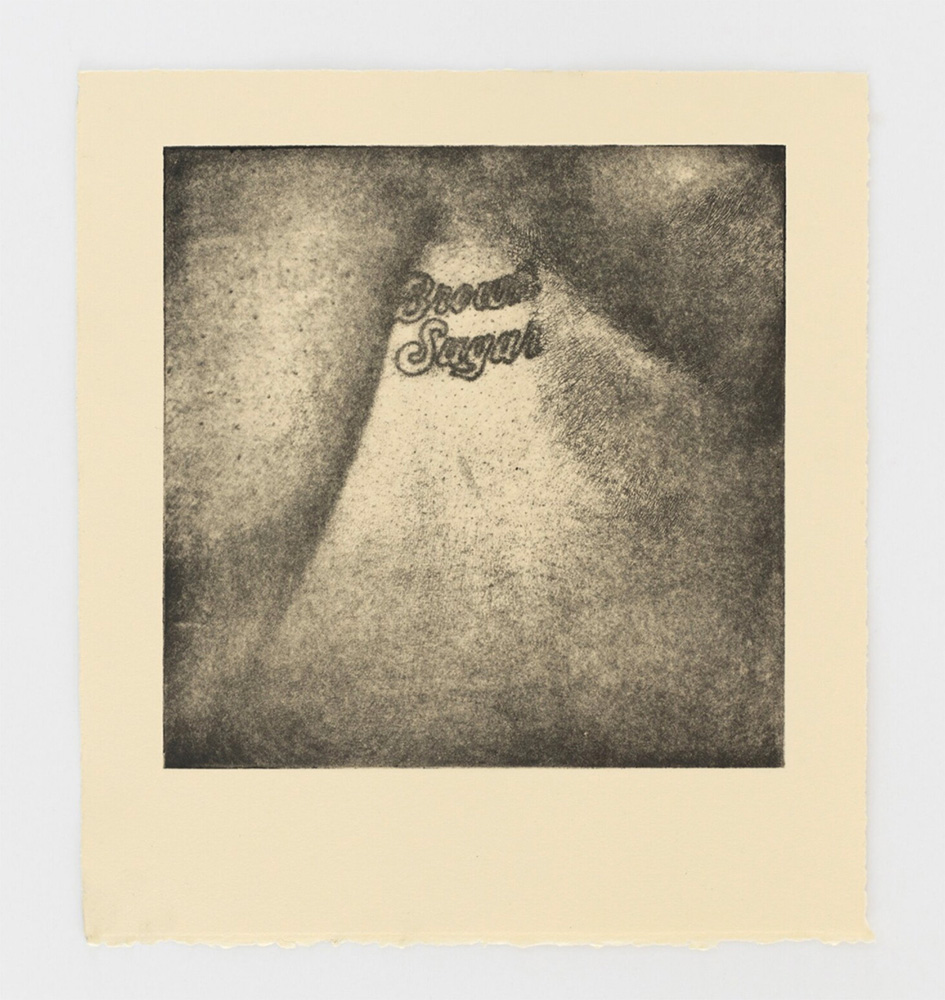

CR: Tender Noted (Shala’s book published by Wendy’s Subway) felt totally influenced by this way of storytelling. I started the book not knowing exactly where it would end. Reading it, I was often surprised by the next page, you’d shift the style completely through a visual or textual element while still maintaining some kind of string. I really liked that.

But also, I think my taste leans towards stuff that takes different angles and different media to treat the same “topic”. I love reconsidering a thing.

SM: Yes! This practice of reconsideration is always something that’s exciting to me.

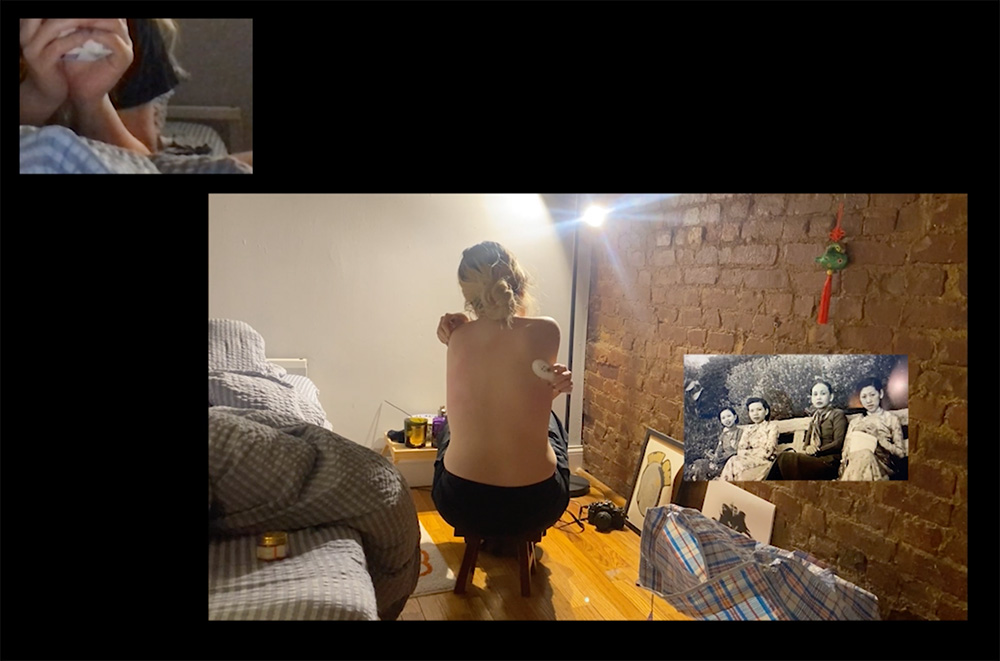

CR: Can you speak more of navigating private and public explorations of selves, desire, mourning and anxiety?

SM: For Tender Noted, I think it was a way of working where I didn’t have much of a separation between my private life and what was public in my practice. Then right after this, I started Obsidian. I wanted to talk about a kind of rage and grief that were all-consuming, but through some distance between myself and the audience. It’s giving it some levity that was necessary for me. I’m back to that kind of thinking. These days, I want to write about this recent procedure I had to go through and dealing with the hospital, the health care system, and all that bullshit. Something I find exciting about having private and public enmeshed a little is that I have found other people moving through similar things. I love talking to other people, and I mean, it sounds corny, but truly not feeling alone in that has been great.

CR: This balance is tricky. I find public vulnerability to be quite transgressive. I’m one of those people who used to say ‘oh that’s cringe’ a lot. But there’s something to earnestness that I think we need right now. I’ve become more unfazed by super guarded work. Yet at the same time, I wonder if that’s just the product of social media and whatnot, that thing where our private lives need to be performed to a public. I guess that doesn’t translate to actually being vulnerable. I mean “public” and “private” were always linked…the words for what I’m trying to talk about are hard to find.

SM: Even if you do try to separate the two, it will always exist in a certain amount of precarity. That separation is eventually going to collapse.

CR: Can you speak more about your baking?

SM: My late father and my mom are fabulous chefs. Apparently, my grandmother on my mother’s side was especially an amazing baker. I mean, they all learned from their mothers.

My dad had a terrible sweet tooth and would bake a lot. So I blame him for my addiction to sugar. My dad was like the matriarch, even though he was kind of like macho or whatever. But growing up with his mother, he was taught how to cook, do the laundry, and other house stuff.

A year prior to his passing, he showed me how to make a rice pudding.

That was one of the main things he made, and he did not tell anybody his recipe. He told his brother, my uncle, and then he told me.

Through lockdown, I perfected the recipe. It made me feel connected to him.

Baking is also a way for me to calm down. I love making really difficult-to-bake recipes, something that will take me all day.

CR: This reminds me of a video I saw recently where a mother in Japan had made a stew before passing away, and the dad and the daughter put it in the freezer and hadn’t touched it in years. 5 years later, they tested if it was still edible, and it was, and so the video was them trying this stew for the first time in so long. I cried.

SM: Or like the baked ziti from the Sopranos. You’ve seen the Sopranos?

CR: Some of it. We’ve already spoken about it. Shala film bro is back…

SM: We have? Okay, well what are you waiting for dude! No seriously it’s a very good show.

CR: I know, I know! I will, I promise. Okay, last question.

Can you describe the image you haven’t made yet?

SM: First thing that comes to mind. It’s a dramatization of a moment I had after my surgery. I couldn’t bend and see the scars, so I’d use this flashlight and mirror I’d keep next to my bed to see what my scars looked like and if the stitches were okay. The colors of the lights from my room differed from the ones of the flashlight, and I remember thinking, ‘Oh man, this feels like a moment of quiet theater’.

There are so many details that I saw in the room that I want to capture. I’ll take it from my imagination on a large-format camera.

Cléo Sương Mai Richez is an artist and writer based in Brooklyn, NY. Her work is interested in our relationship to the real and our agency within it. This most recently took the form of an exploration of people’s relationship to their parents, asking if it is possible to kill them before they die. To figure that out, she worked with performance, writing, moving image, drawing, objects, and installation.

She holds an MFA in Photography from the Pratt Institute and a BFA in Film & Television from the London College of Communication.

Instagram: @richezcleo

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025