Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya Marcuse

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Emma Ressel and Tanya Marcuse are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

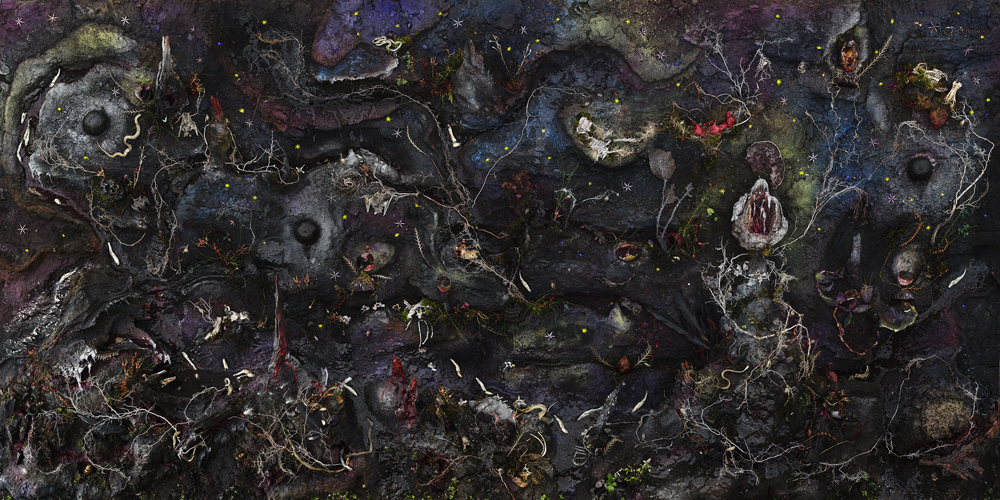

I first encountered Tanya Marcuse’s work when she substitute taught the class I was taking with Stephen Shore my sophomore year at Bard. That day, we were learning about the view camera’s tilts and shifts, and she brought in work prints from her then in-progress series Fallen to demonstrate how she tilted the focus plane of the camera to parallel the slope of the forest floor. The images transformed me. I was struck by how she elevated something as base as the rotten apple and swampy ground into a velvety wonderland. That work clearly influenced my senior project at Bard, which resulted in still life compositions made with a view camera of foods and animals. Tanya’s work expertly traverses the ridge between reality and artifice, which is a perpetual consideration in my work as well. I have become only more enthusiastic about her work over the years, and I was thrilled to speak with her on a hot summer day to ask the questions I have wondered about for a long time.

Tanya Marcuse (born NYC) is an American photographer most known for her large-scale photographs that explore the imperiled natural world. Her projects use increasingly fantastical imagery and elaborate methods of construction to explore cycles of growth and decay and the dynamic tension between the passage of time and the photographic medium.

Tanya Marcuse earned her MFA from Yale University. Her work is in public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the George Eastman Museum, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. Marcuse is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Peter S. Reed Grant, an American Scandinavian Fellowship, and two MacDowell Fellowships. Her published books include Undergarments and Armor, Wax Bodies,, Fruitless | Fallen | Woven, Ink, and Portent.

Tanya is a student of martial arts and boxing as methods of cultivating mental and physical discipline. She teaches at Bard College and is based in the Hudson Valley.

Instagram: @tanyamarcuse

Emma: Before I started recording, we were talking about specific places in your immediate surroundings of the Hudson Valley, and I want to begin by asking if your work is ecologically specific to the place you live. This morning I was in the Rio Grande bosque here in Albuquerque, the forest surrounding the river which runs through the city, and this time of year the cottonwood trees are releasing this amazing fluff that carpets the ground. It’s an incredible texture, kind of like a dusting of snow. I was looking at the ground and thinking of talking to you today, and I was imagining a Woven piece composed with cottonwood fluff. But, you don’t have cottonwood trees where you are, so would that ever be a material you would use, or are your materials specific to where you live and work?

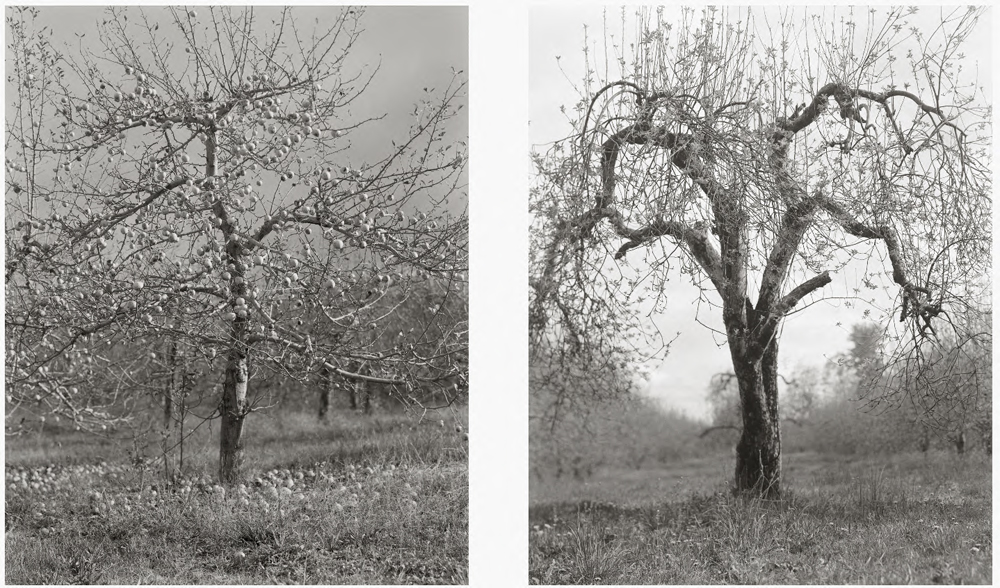

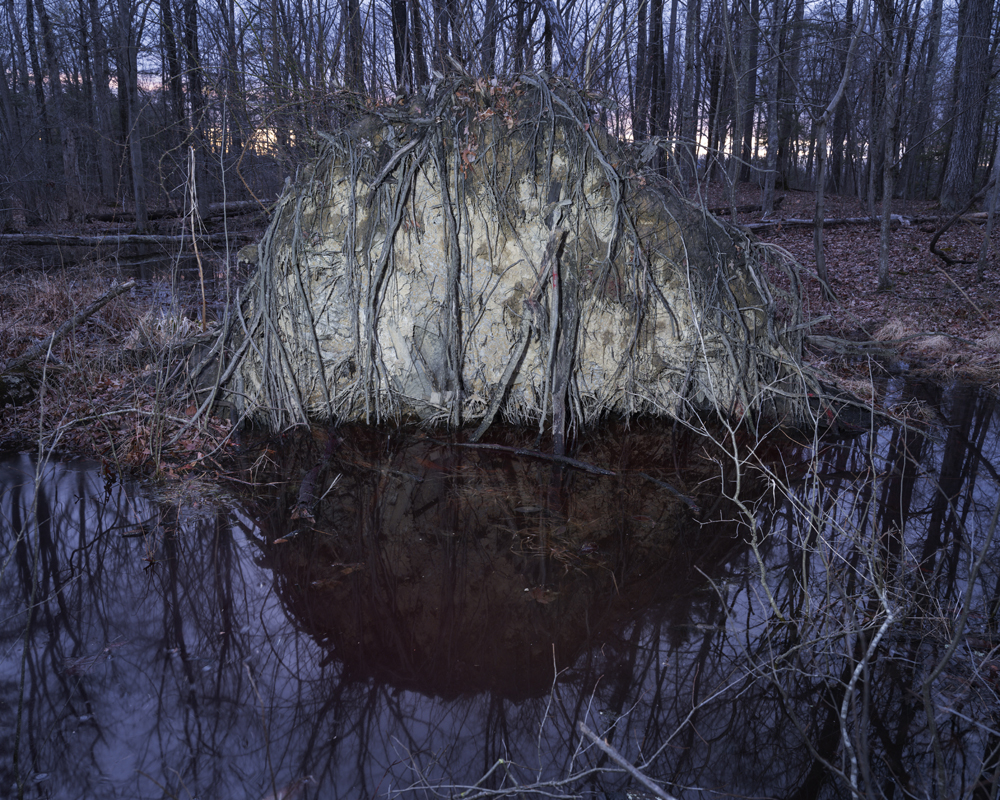

Tanya: I think the answer is yes and no. Woven was more naturalistic and its ingredients more regional. But in my new project Book of Miracles I’d welcome the cottonwood fluff. In some ways, my work is deeply specific to the ecosystems of the Hudson Valley, where I’ve lived since 1991. The Fruitless project that I began in 2005, photographing apple trees on land that was for sale, was specific to this area in a more factual or indexical way, but of course, something can always hinge from the specific to the metaphoric, the allegorical. In Portent, Part 2 of Book of Miracles, my more recent project, I’m staging scenes in the local landscape, often within just a few miles of home, so those images are more tied to the reality of this area. In Part 1 Kingdom and Part 3 Emblem, I’m working under the studio tent in my backyard to create elaborate tableaux on a wooden frame, so it is important that Portent binds the fantastical elements running throughout the project to the landscape around me.

E: In making the Portent chapter of the Book of Miracles, were you experiencing an urge to be back out in the world to see what’s there in front of you, rather than under your tent and on the frame?

T: It’s a great question because in Woven, the project just before Book of Miracles, the images were entirely made on the frame under the tent in my backyard, but I was constantly going out to the woods to collect and observe, which becomes a reciprocal, rich, experiential relationship. When I started Portent, which is still ongoing, I wasn’t sure if that series would even be part of Book of Miracles. (I usually have one main thing that’s happening in my work, and then many sub-practices that are happening while the main work is unfolding.) I was experimenting with fire, with lighting, and then thinking about the way in which the greater illusion of “reality” which comes from being out in the landscape could be in conversation with the fully constructed tableaux.

In the tent, I’m working to create a sense of immersion for the viewer, but I’m not immersed in the landscape when I’m under there. I can see the edges of the frame. However, it is an unbelievably intense experience for me. When I’m building those pieces, the level of obsession is almost uncomfortable. It completely takes over my whole life. I’m waking up at 3:00 in the morning, making lists, notes, looking up things from literature, from science, from picture books of frescos, of Jackson Pollock, etc. I’m in this state, and I’m trying to figure out all of these things ranging from compositional questions to technical questions and logistical questions: will certain things be safe to leave on the frame? What is so perishable that it has to wait till the last minute? It’s consuming and the sense of investment is honestly absurd, especially with everything that’s happening in the world. There’s an absurdity to the drive, but I accept it. Another wonderful aspect of the Portent pieces is that they can happen in one day, or sometimes even a few hours, though some need more planning. I might have an inkling of what I want to do, I might bring some materials somewhere, but I never really know, so that’s a way for me to work with photography in an immediate, improvisational way, which I love.

E: I wanted to ask you about obsession. It’ss really interesting to hear you talk about that quality of making the Woven work, and I’m curious if that also happens when you are out in the woods making some of the more “found” images like in Portent. Is there a similar obsession that drives you to go out and spend time out in the landscape?

T: It feels a little different, but yes. To give you a very specific example, somehow or other, for all the years that I’ve been living here, I was not that tuned into the great amphibian migration that happens in the spring. Then, I was talking to someone, and they were like, “Oh, are you going to be out for the Big Night?” I ended up working with some local volunteer organizations to help amphibians cross the road during this big night when the temperature is above 50, there’s a rain, and the amphibians migrate to vernal ponds. This year, there was a dramatic, big night in April. It was pouring and despite my raingear I was soaked to the bone, directing traffic and gently lifting up peepers, wood frogs, salamanders and other creatures to carry them across the road. That week I was out every night making photographs in the vernal pools, surrounded by a deafening cacophony of mating calls. These experiences are totally ecstatic, addictive.

I’ll just be honest, these are completely transcendent experiences for me where I feel like what I’m witnessing is an encounter with the unknown. In making and lighting the photograph it becomes theatrical as well, so there’s this introduction of artifice into the wild—and the term “wild” is a little complicated—but wild, less controlled environments. I’ll have these hot streaks – the early spring was totally feverish this year. I would teach, then go out between 6pm and 1am. Sometimes things don’t come together, but when I do get to experience those otherworldly, extraordinary experiences, it’s really hard not to chase after them. I guess some people do bungee jumping or things like that. Before we started recording, I was talking about how amazing it is that this is all right around me. That suggests something powerful to me, which is that this other, more unknown realm is in plain sight, but we need to be present for it and let ourselves be open to it, whatever that means.

E: Right, and I think that it takes a lot of time and sustained attention for nature to start opening itself to us and to be able to start reading and understanding things. I love that you mentioned the Big Night, because that is something that I am pretty familiar with. My dad is a herpetologist in Maine and for many years he’s been studying a certain population of spotted salamanders. Every year, growing up, we would go out for the Big Night. In Maine it happens around the first week of April, and every year at that time, I still feel it a little bit, you know?

I was missing the Big Night when I was working on my thesis project and wishing I could be there to help them cross. I’m really far away now, so I ended up going to one of the natural history museums where I had been working and asking to see their collection of spotted salamanders. In my work, missing the event and not being there to witness it transforms into this other longing to go to the natural history museum to see the approximation of the thing. One of the reasons I think I am so continuously drawn to your work is that I see you there, in proximity to the thing, which for me is this distant memory/experience.

T: That’s completely incredible, Emma. You should send me your dad’s research and we should maybe talk at greater length about those childhood experiences of helping to move the salamanders and wood frogs and peepers. That’s a great little vignette you described, where you didn’t have the physical proximity, but the natural history museum, both in its collections and dioramas, creates that sense of a stand-in for the natural world. I can’t stand that phrase, “the natural world”, but I haven’t quite figured out another way to say it. As if we’re not part of “the natural world”!

©Tanya Marcuse, Nº5634, Book of Miracles (Part II Portent) , 30 x 38” 2025 (vernal pond on the big night)

E: I think of it like we are in this really awkward relationship to the natural world. We are in it, but we think of ourselves as apart from it, and it’s hard for us to make sense of that.

I know you have studied dioramas as part of your research for the work you’ve been making. Could you talk a bit about what you’ve found, and how you think about dioramas in relation to your work?

T: I also had very powerful experiences in the American Museum of Natural History as a kid. I actually wrote about this in a little piece I did for The Bardian called “Window on Nature”. I had incredible experiences as a kid looking at these dioramas, including getting lost on school field trips – the first time by accident, the second time on purpose. I see the dioramas as embodiments of the dichotomy between imperialist plunder and conservation. It pains me that they are being dismantled, like the one in DC – I’d be really curious what your perspective is about this. I’m very empathetic towards the impulse that it comes from, but I wish they could just be studied and contextualized, rather than basically destroyed.

There’s something intriguing for me about the space of a diorama, the unbelievable compression of the number of species visible in a small space, which I borrowed in Woven. It’s believable but exaggerated. There are elements that are real, but they’re translated into a new language, so I actually think there are a lot of syntactical analogies between photography and the diorama. A lot of decisions have been made by the dioramist about perspective, vantage point (to some extent), and moment. In Woven and in the large tableaux in general, rather than have an illusion of three dimensional space that recedes, space is totally compressed on the picture frame. Photographs are flat, but most suggest an illusion of space, the way that a painting might use perspective to give an illusion of space. I’m very specifically borrowing from abstract painting, which insists on the surface, like a Pollock where everything is compressed. If there’s depth, it’s a very shallow depth, at least in Woven.

In recent years, I’ve made very specific “field trips” to the Natural History Museum to study certain things. When I was working on Woven I wanted to make some pieces that were more wintery, since there were these seasonal shifts in the work. I had a contact through a friend, and they gave me a bunch of pro tips about how to make fake snow. I was working on Woven Nº 31 during a cold snap in February– collecting icicles from Bard Falls and lashing them to my frame with fishing line–but it was about to warm up. I was estimating that I would need at least another two weeks for the piece, and then suddenly I’m shooting it in four days. I had to really expedite matters. In that piece, I put a lot of my specimens in the freezer and froze them in Tupperware containers so they became little ice fossils. I wanted to make visible that though it was winter, all the seasons are present, even when you can’t see them. Perennials are underground. The diorama, too, begins with life, then moves to death, then moves to life-like. It’s an interesting trajectory that I want to enter into and problematize.

E: I think about how once the animal is taxidermied or the diorama is assembled, there’s a second life that begins. When I was working in small natural history museums I was asking to see the backrooms, where the taxidermy was really old and falling apart, and I started thinking about this second death and decay that happens. We make this attempt to preserve and prevent the decay, but it’s futile. What you’re describing with the traces of other seasons in the winter scene makes me think about collapsing, disruption, or distortion of the cycles of life and death. I think dioramas do this by packing in so much, and resulting in a complication or multiplication of moments.

T: Yeah. I love what you’re saying about the second decay. The human hubris in killing and preserving the animals is the existential piece, as if we could stop decay or death. What a great image of the behind-the-scenes taxidermy, where the frame hasn’t held up or the skin falls off.

In Woven Nº 31 I include cardinals, snakes, and delphiniums, which would never be seen in the winter, making a leap beyond plausibility that a diorama would not. Even though the natural history diorama is not quite plausible, mine takes another step towards implausibility.

E: Speaking of decay and cycles, I wanted to ask if you could talk about the Valley of the Vultures.

T: Valley of the Vultures is a case in point about finding another world in plain sight. You know the Valley of the Vultures, as a Bard student.

E: Well, not really. I remember seeing vultures all the time at Bard, and I knew they were somewhere, but to me as a student, I didn’t know where, they were just outside of my understanding. It was always a curiosity, but I never tried to find them.

T: It’s simply—it’ll probably ruin it for you—but it’s the recycling area, behind where you went to school and where I teach. It’s very distracting for me. I’ll be coming to teach, and I can tell that there’s a lot of activity back there and it’s like oh my god, how am I gonna focus. Once, I was in the ravine back there, which is actually very hard to climb down into, and I remembered a senior was having an opening. I was down there, covered in meat, blood, and mud, but I had a cute skirt underneath my chest waders, so in a very 007 move I just peeled off the waders and there I was in my corduroy skirt with a little glass of white wine.

© James Romm, Tanya Marcuse working

Right now the place I call The Valley of the Vultures is very uninteresting to me because the green is so overwhelming. Last summer I tried all summer long to make something interesting there despite all the green, but I didn’t like the fact that the trees were so crowded. Now, I don’t really work there in the summer, but I still go to feed the vultures and keep up the relationship. I have an idea that I’m like a zookeeper; I carry the same white bucket of food to them each time. It’s all still underway, and I actually think the most important work for the project will end up being a film, which is still evolving.

As Woven was coming to a close I began incorporating more living creatures –rescue owls and frogs in a spring woodland scene – realizing that if the work was truly about cycles of life and death, it needed more life. With Book of Miracles, I turned to vultures. Their lives are sustained by carrion flesh, so they’re at the absolute axis of that relationship of life and death. Their relationship with death that becomes life is completely extraordinary. Vultures mate for life and don’t eat other vultures, which is something one could ponder, that they know the difference between a vulture and another species of dead bird that they will eat. All of these things I find utterly fascinating.

In April, I visited the vultures when it had been raining and there was a puddle that looked like a lake, and on either side the vultures were hanging out on top of mountains of mulch. (I omit all of the human-made stuff in these photographs, not through Photoshop but through framing and vantage point.) This was a shoot that took more planning and a few failures. There were times I couldn’t get the vultures to be interested in anything I was offering them. I’m seeing myself a little bit as a director, trying to create a stage, trying to entice them to do this or that with my little gifts. It’s a bit absurd.

© Tanya Marcuse, Nº 5980 Book of Miracles (Part II Portent) , 38 x 30” 2025 (Valley of the Vultures)

Sometimes, things truly, fully come together. You get a random reward, which isn’t so random, because as you were saying it’s about continually showing up and paying attention. I finally did make a picture and some footage that I totally love. I had brought many of my collected deer skeletons, various forms of meat, blood, etc, and I had carefully picked out some garbage floating in this puddle with a little grabber tool. I had this little mountain of bones and meat in the puddle and the vultures were flying in and eating it. The light came together, and the fog machine…

E: You brought a fog machine into the ravine!?

T: Yeah. I didn’t want to try it until I had gotten something. You know how sometimes you get a picture, and then it’s a feeling of okay, now I can try things. Usually from there, things get much more interesting and I’m willing to fail and experiment. That was thrilling, totally euphoric. The satisfaction is as deep as the disappointment of those other experiences.

In the Portent pieces, it’s a good sign when I feel like I’m bearing witness to an event, even if it’s something I had a very strong hand in creating. The editing of the work is tricky, because in some my hand is much heavier than in others. I’m still considering omitting some of the pieces where my hand might be too strong. It’s richer to get to a place where the photographs hover between something that could plausibly be discovered and something that is clearly artificial.

E: I wanted to ask, what is your tolerance for failure? In my work, I avoid this high margin of error by photographing dead and mounted animals that aren’t going to move. What you’re talking about sounds like nature photography, with all that goes into the staging, waiting, and creating frames for the animal to walk into. It sounds like you are taking on some of those technical tropes, but obviously making something that exists in your own, imagined worlds.

T: It’s a great topic, the whole genre of nature photography. Nature photographers show up with a million cameras and tons of resources, and I absolutely cannot compete with that. This is very freeing: since I absolutely can’t do that, what is it that I can do?

I would say my tolerance for failure is high. Not only in filming the vultures, but when I was transitioning from Fallen to Woven, it took me a solid year to figure that out. I had an instinct about the 1:2 aspect ratio – I knew I wanted them to be bigger, but I thought I could use an 8×10 view camera and I was still working on the ground. In order to get to the frame, there were months of trial and error, and error, and error. But, it was all instructive. For example, with the 8×10 view camera, the image would look great in the center and then fall off, as a conical lens will do. There’s just no way to avoid it. Wanting to solve that problem helped me to understand how important it was to have a democracy of description, not prioritizing the things in the center of the frame. Figuring out how to do that, moving to digital and stitching together multiple frames taken from different vantage points, totally changes what the work looks like and what it means.

E: As a photographer, switching tools and the entire way of working is huge.

T: Speaking of failure, I’ve recently started working in film, and I feel totally humbled by it. I used to make fun of still photographers who would make a video for their show. How do you change language like that? The relationship with time is totally different. Durational time, time unfolding, no object per se. I’m a very object-oriented photographer, so I think about how something resolves as an object, as an installation. I think I’m a white belt in film.

E: You say you’re a white belt in film, and I wanted to ask you about your martial arts practice. I know it’s another big part of your life, and I’m curious how you think about training, discipline, and if it relates to your work.

T: It does feel all related. I started martial arts training 10 years ago when I was 50.. I have a kind of excess energy, so I have found that the training, through endorphins, discipline, and concentration, burns me down to a more lucid place. I trained this morning and it was so hot, I thought I was going to throw up. But I didn’t sleep much last night because I was so worried about political dynamics and various other things, and I can’t do very much about that myself today, so it’s better for me to be in this somewhat more centered place.

There are a lot of things about martial arts that are analogous to photography. It’s a language of its own. Forms, techniques, discipline, and attention to detail are huge. It’s a relief that originality is not a goal. I’m a second degree blackbelt now and I have gained an understanding of Tang Soo Do, but I also feel like I’ve only just begun. My phone is off when I’m training, and it doesn’t work when your mind wanders. It’s dangerous, for one thing—you could get hit in the face or something. Being physically strong helps me when I’m climbing into a ravine carrying two tripods and wearing heavy boots. I don’t know how long I’ll be able to work this way, which is something I’m aware of as I get older. This spring, I was thinking how many more springs will I even have, and for how many of them will I be able to be out in the swamps and the woods taking pictures?

E: This factor of the elimination of the excess and the resulting focus is so related to composing photographs.

T: Yes. Whether it’s underneath the canopy on my frame, or whether I’m out with the vultures, or standing in a vernal pool, there is that sense of total engagement, and that is tremendous.

Emma Ressel (born Bar Harbor, ME) is an artist working with large format film photography, re-photography, and archives. Her current work researches natural history collections to examine how we describe nature to ourselves over vast timescales. Ressel earned her BA in Photography at Bard College and her MFA at the University of New Mexico. She has exhibited solo shows at The New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque, NM and Strata Gallery in Santa Fe, NM. Her work is in permanent collections at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Museum of Jurassic Technology. Ressel was on the shortlist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, and in 2022 she won the Film Photo Student Award. Her first photobook, Olives in the street, was published by Edizione del bradipo in 2017, and she has since self-published 2 additional photobooks, Glass Eyes Stare Back (2024), and Extant Erosions (2025).

Ressel is currently a Post-Doc fellow at the Center for Regional Studies at University of New Mexico. She lives and works in Albuquerque, NM.

Instagram: @emma.ressel

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026