Photographers on Photographers: Lydia McNiff in Conversation with Sonja Langford

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Lydia McNiff and Sonja Langford are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

I first discovered Sonja Langford’s work right here on Lenscratch–a publication I turn to regularly, especially for its thoughtful features of women artists. Her photographs immediately struck me with their austere, harrowing beauty and deeply resonant subject matter. As someone who also explores themes of gynecological care in my own photographic practice, I felt an instant connection to the emotional and political terrain she navigates.

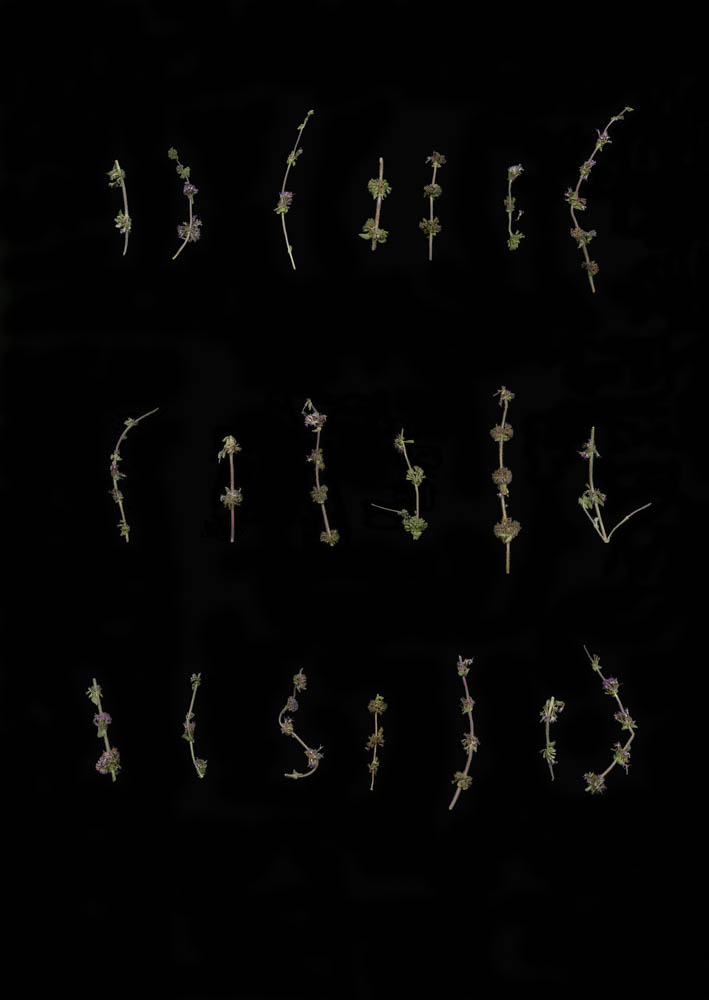

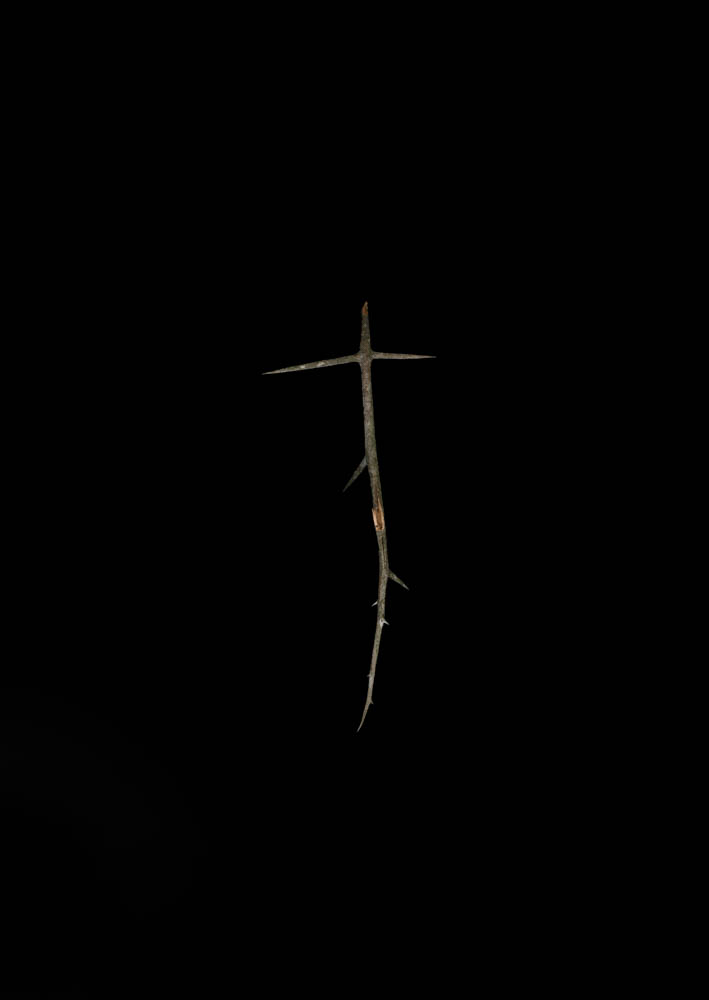

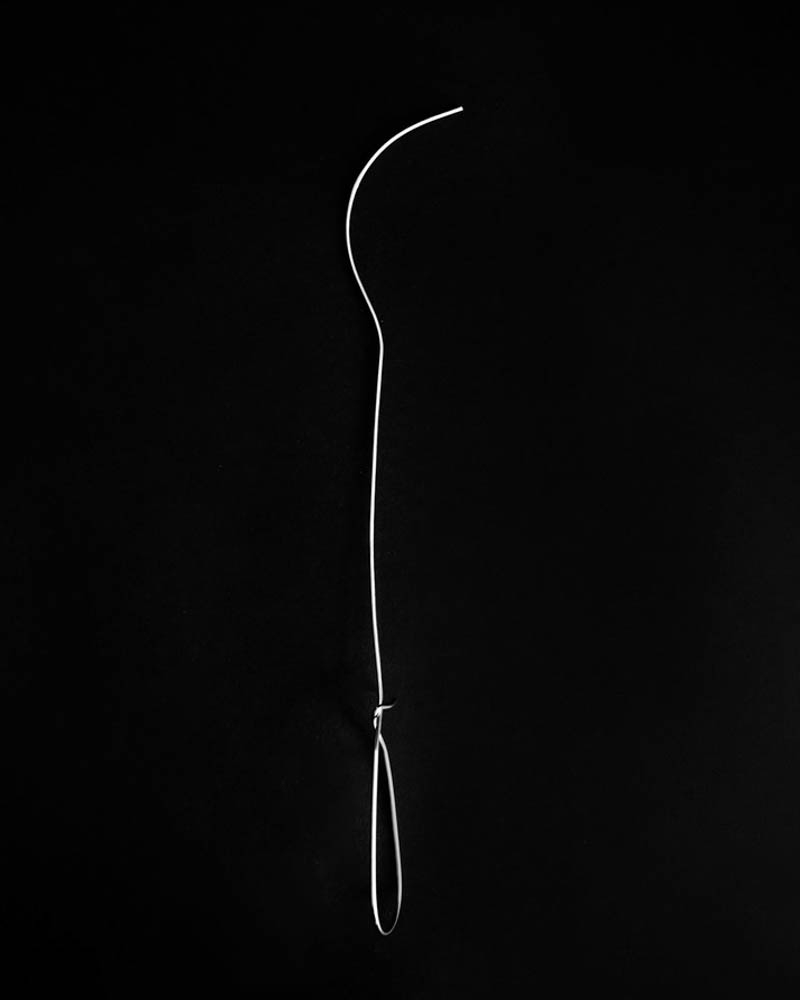

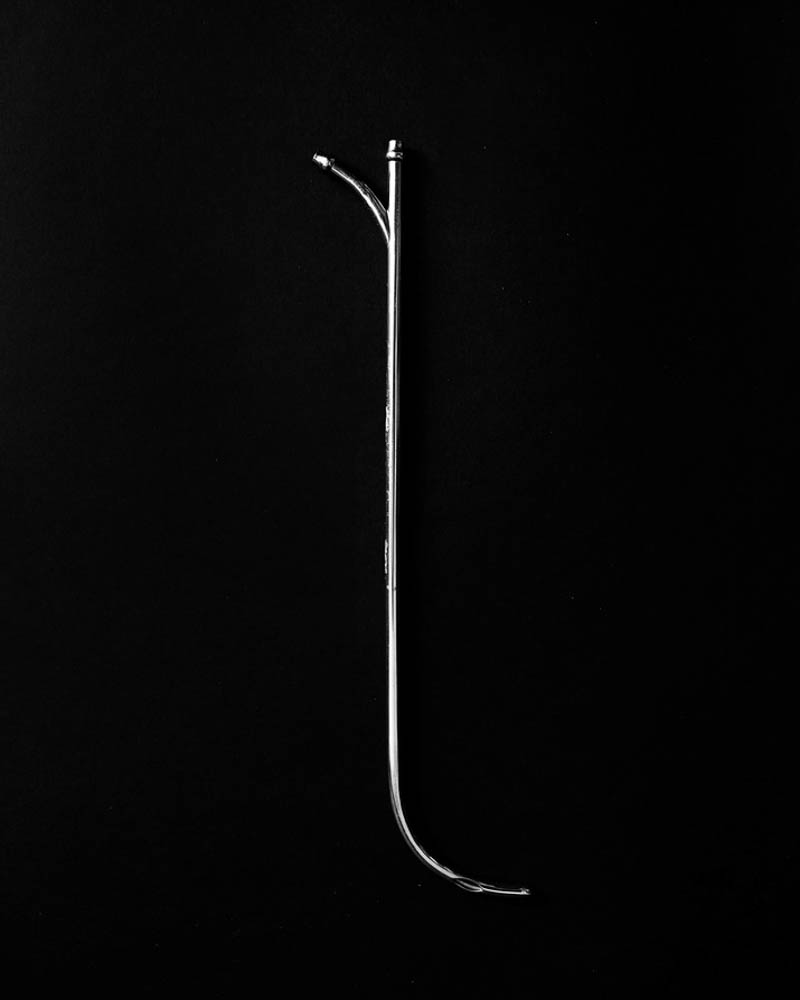

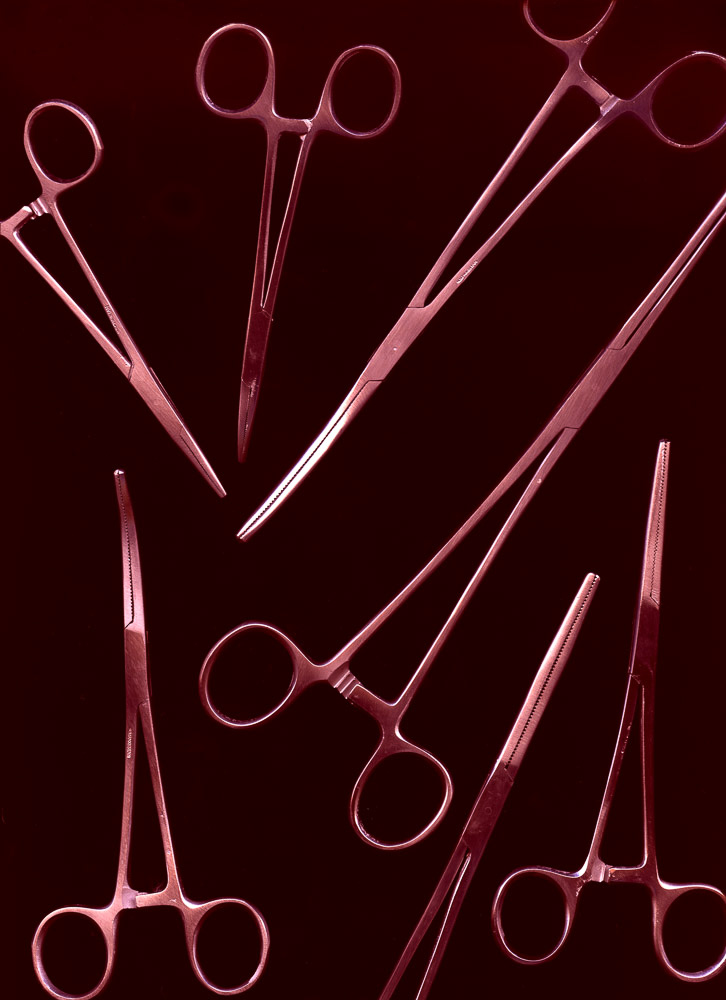

Sonja’s work confronts the often invisible, frequently neglected realities of women’s healthcare. Her images create space for pain, resilience, and vulnerability, while inviting both unease and curiosity. Her series Gynecological Instruments is especially striking to me–she deliberately places these clinical tools in full view, challenging cultural discomfort and prompting reflection on their sometimes violent sterility.

I admire her courage in laying her pain bare–a profoundly vulnerable act. As someone personally affected by the failures and gaps in our healthcare system, I am moved by how Sonja translates these experiences into visual language. It was an honor to interview her, and I look forward to seeing how her work continues to evolve and inspire.

Sonja Langford (b.1994) is an artist and researcher raised in the American South. She is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Connecticut and holds a BA in Art History with minors in Southern Studies and Outdoor Adventure Leadership from the University of North Carolina Charlotte. Sonja’s work has been exhibited in numerous venues, including the Gadsden Museum of Art (forthcoming), the McColl Center, and GoodYear Arts. Her practice engages with photography, bookmaking, social practice, archival research, and installation, exploring themes of medical history, gender, and power. Through her research on American gynecology, she investigates the intersection of history and contemporary healthcare disparities, highlighting how past narratives continue to shape present realities. Her work seeks to challenge perceptions of visibility and control within medical and historical contexts, bringing to the light the overlooked and unseen.

Instagram: @sonjalangford

Artist Statement

There is a rhythm to loss, a structure to forgetting. My work traces the ways history inscribes itself onto bodies, onto institutions, onto language. I work with text, material, and form—not to create resolution, but to hold space for what lingers, what resists being erased. The archive is incomplete. The record is not neutral. The body remembers even when history forgets.

My work sits at the intersections of history, medicine, and gender and examines the overlooked and often unsettling narratives embedded within the archives of American gynecology and the persistent impact of its legacy. Through installation, archival activation, and social practice, I investigate the ways medical systems shape bodily autonomy and care, illuminating the widening gender gap in healthcare, studies, and funding. Much of my research is rooted in the American South, a landscape where history is never still, where past and present collapse into one another.

I return to language as both subject and material. I take what is written—medical texts, institutional records, historical accounts—and examine where it fails, where it leaves gaps, where it obscures. Words can be stable or unstable, fixed or breaking apart. I let them unravel, stretch, contradict. The process is slow, deliberate—like transcription, like excavation, like trying to listen for something just beneath the surface.

My work is not about spectacle. It is about presence. Some things are quiet but insistent. Some things sit just at the edge of collapse. I make work that holds tension, that presses back, that asks something of you. Because these histories are still moving. Because these questions are still urgent. Because the body carries what the archive cannot.

I would be doing you a disservice not to mention that I (and by extension my practice) am haunted by a few things: namely the American South, religion (specifically a high control religious group in which I grew up and sometimes refer to as a cult), and the relentless search and reward found in an archive.

Lydia McNiff: How did you first become interested in the history of American gynecology, and what motivates you to keep exploring that subject?

Sonja Langford: My interest in American gynecology began out of necessity—I was diagnosed with endometriosis and adenomyosis after being dismissed and misdiagnosed. That frustration turned into a deeper desire to understand how and why gynecological care in the U.S. feels so alienating and, at times, violent. When I began digging, I found an entrenched history of violence, experimentation, and erasure that still shapes contemporary care. I find myself motivated by the knowledge that this history is not in the past—it reverberates in exam rooms, in the lack of funding for gynecological research, in how pain and care are treated differently based on race, gender, and perceived credibility. Making work about this is my way of metabolizing it—turning it into something legible, shareable, and hopefully even capable of shifting perception.

Lydia McNiff: What has the response to Gynecological Instruments and The Forgotten Emergency meant to you—both as an artist and as someone engaging with these issues personally?

Sonja Langford: The bodies of work I’ve made about these topics are the most personal and difficult works I’ve ever made—and also the ones that have generated the most conversation. I’ve had people come up to me, sometimes tearfully, saying they felt seen in a way they never had before. And I’ve had the opposite response: people upset that I’m making this work because they don’t see themselves reflected in the work and don’t know how to engage with it. The first reminds me that this work isn’t just about my story or a singular historical story; it’s about a shared experience of neglect, silence, and survival. As an artist, that kind of resonance feels like a form of care in itself. It tells me that the work is functioning not just as critique, but also as connection. I’m understanding more a large part of my art is social practice.

And the second type of response, from those upset with my work, tells me that the discomfort is doing its job—that the work is asking something of the viewer. Not everyone will relate directly, but I think art can still create a space where unfamiliar experiences are encountered with empathy rather than dismissal. If someone feels unsettled, excluded, or even implicated, that’s often a sign that the work is confronting something real. I don’t make this work to be universally palatable—I make it because these histories and present-day realities deserve to be seen, even if they’re hard to look at.

Lydia McNiff: Can you describe your research process on American gynecology and explain how it informs your creative process?

Sonja Langford: My research practice is pretty hybrid—part academic, part embodied. I read a lot of archival medical texts, historical narratives, and patient testimonies, but I also pay close attention to the language used in my own medical records. I look there because it often reveals power dynamics or bias through tone, omission, or categorization. I’m always asking: who is being centered in this text, and who is being left out? That critical lens then informs how I approach material and form. For instance, I might use medical gauze or exam table paper not just for texture, but because those are materials that hold the residue of bodies—touch, pressure, tension. My research always finds its way into the physical process of making, often quietly, sometimes directly.

Lydia McNiff: How does shedding light on the unseen or overlooked take on a new meaning in your artistic practice right now?

Sonja Langford: The stakes feel higher now. As rights are being stripped away and access to care is diminishing, the silence around women’s health becomes even more dangerous. Making this work is both an act of resistance and a way to document what’s happening. I think there’s power in visibility, especially for subjects that have historically been hidden, shamed, or ignored. I also believe that art has the distinct capacity to hold grief and anger without flattening it—and I think that’s crucial in this moment.

ydia McNiff: How has your upbringing in a controlling religious environment and the American South shaped your artistic practice?

Sonja Langford: That upbringing taught me a lot about control—about who gets to speak, who gets to be believed, and how power can be embedded in care. It made me sensitive to language, to the weight of what’s said and what’s left unsaid. Growing up in the South shaped that awareness too—not just through its histories, but through its rituals, its warmth, its deep sense of place. There’s a particular kind of storytelling, silence, and symbolism that I carry with me from that context. It informs how I think about space, memory, and the emotional undercurrents that live inside formal or institutional structures.

Lydia McNiff: If you could tell your younger self one thing about the transition from girlhood to womanhood, what would it be?

Sonja Langford: The transition from girlhood to womanhood, if there even is such a thing, has never felt linear or clear to me. It’s more like a layered process—of unlearning, adapting, grieving, and coming into language for things that once felt unspeakable. I don’t think there’s one lesson or realization that defines it. What I’ve come to understand is that contradiction isn’t a flaw—it’s a condition of being. And that the body often knows things long before we’re able to name them. My work comes from that space—where memory, intuition, and language are all trying to meet.

Lydia McNiff: What has your experience been like with the handmade bookmaking process? How do your material choices contribute to exploring the body’s memory?

Sonja Langford: Bookmaking has been one of the most meaningful (and newest!) parts of my practice—it’s a slow, intimate process that mirrors how I think about memory. The body doesn’t remember in a linear way, and neither do my books. Materials like medical paper or gauze carry a kind of ambient history: they’re fragile but loaded. They hold impression, breath, pressure. In binding those materials together, I’m creating a kind of vessel for stories that aren’t easily told, or that refuse to be pinned down. The format of the book gives viewers permission to move at their own pace, to engage physically and personally.

Lydia McNiff: Was the sterility in Gynecological Instruments and The Forgotten Emergency intentional? Could you talk about your photographic process?

Sonja Langford: The photographs in Gynecological Instruments and The Forgotten Emergency are deliberately stark—shot against black to create a kind of suspended space. I’m interested in the tension between beauty and violence, especially in medical objects that were designed with function in mind, but that now feel almost sculptural when isolated. There’s a strange elegance to some of them—curves, symmetry, gleaming metal—but once you understand their use or history, that elegance becomes unsettling. I want the viewer to hold that contradiction. The lighting, the quiet of the frame, the simplicity of presentation—it’s all meant to invite prolonged looking. And in that looking, discomfort can surface. I’m not interested in these images offering resolution, but rather in how they hold space for discomfort and reflection.

Lydia McNiff (b. 2001, Bloomington, IL; based in Normal, IL) is a photographer currently making work centering women’s health and feminist ideologies. She earned her Associate of Arts degree with a focus in graphic design from Heartland Community College and a Bachelor of Science degree with a focus in photography from Illinois State University. Her work has been exhibited both locally and internationally, including at the McLean County Arts Center, University Galleries at Illinois State University, The Coffeehouse and Deli in Normal, the Springfield Clinic Center for Women’s Health, and PH21 Photography Gallery in Budapest, Hungary.

In 2024, Lydia received the Irving S. and Joan Tick Award for her piece The Pelvic Exam at the University Galleries Student Annual Exhibition. Her series Visceral was also published and recognized that year as a Student Prize Finalist by Lenscratch. Through her work, she seeks to foster dialogue around women’s health, pursue meaningful opportunities within the art world, and engage in collaborative creative practices.

Instagram: @lydiamcniff_photography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025