Yosuke Morimoto: Yoyogi Park, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo

I recently had the great pleasure of reviewing portfolios at the Karuisawa Foto Festival in Karuisawa, Japan. It was great to see photographers who I had met during the 2023 at the Tokyo Photo Festival and see the progression of their work. It was also wonderful to make new connections with photographers like Yosuke Morimoto. Morimoto shared an extensive book project, Yoyogi Park, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo that features photographs taken from 2006 to 2023.

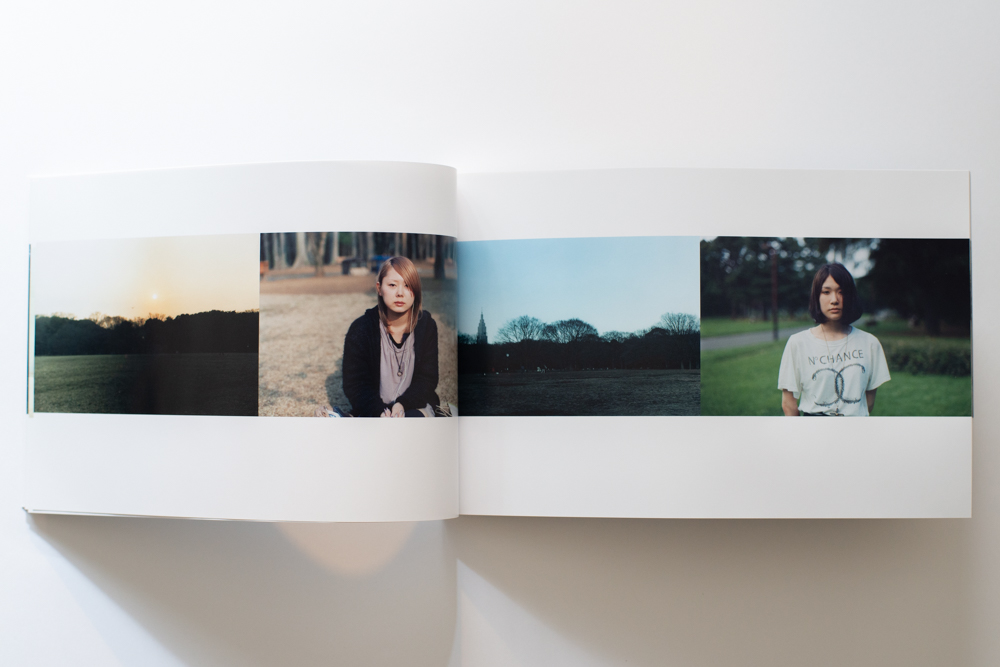

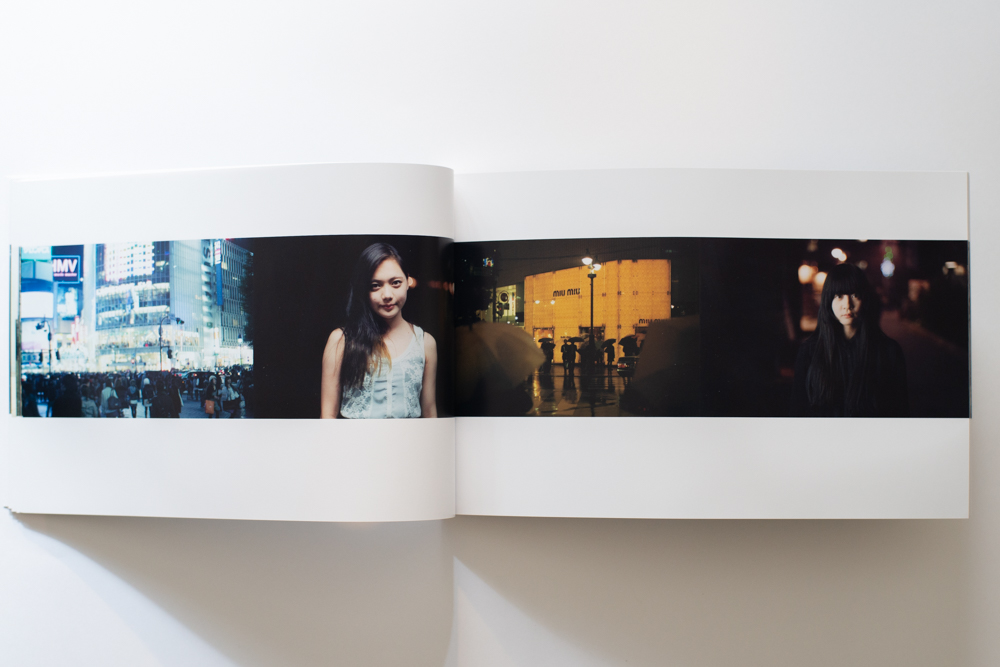

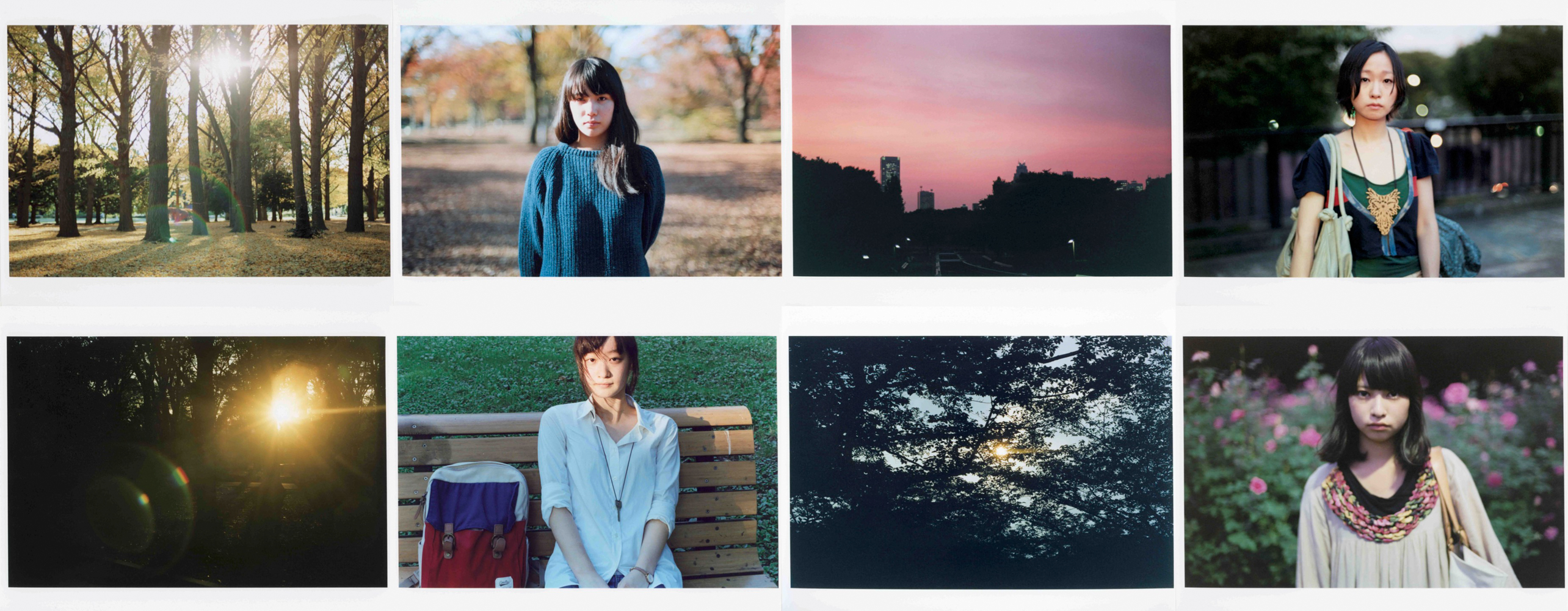

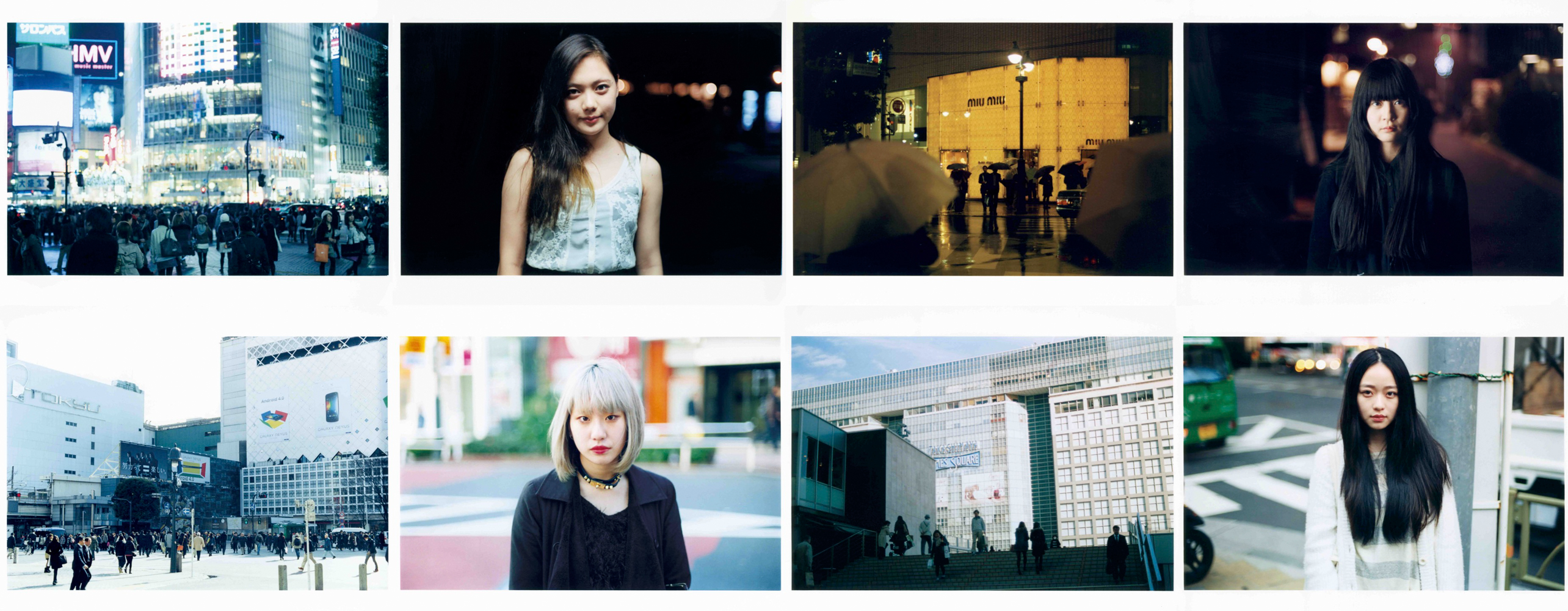

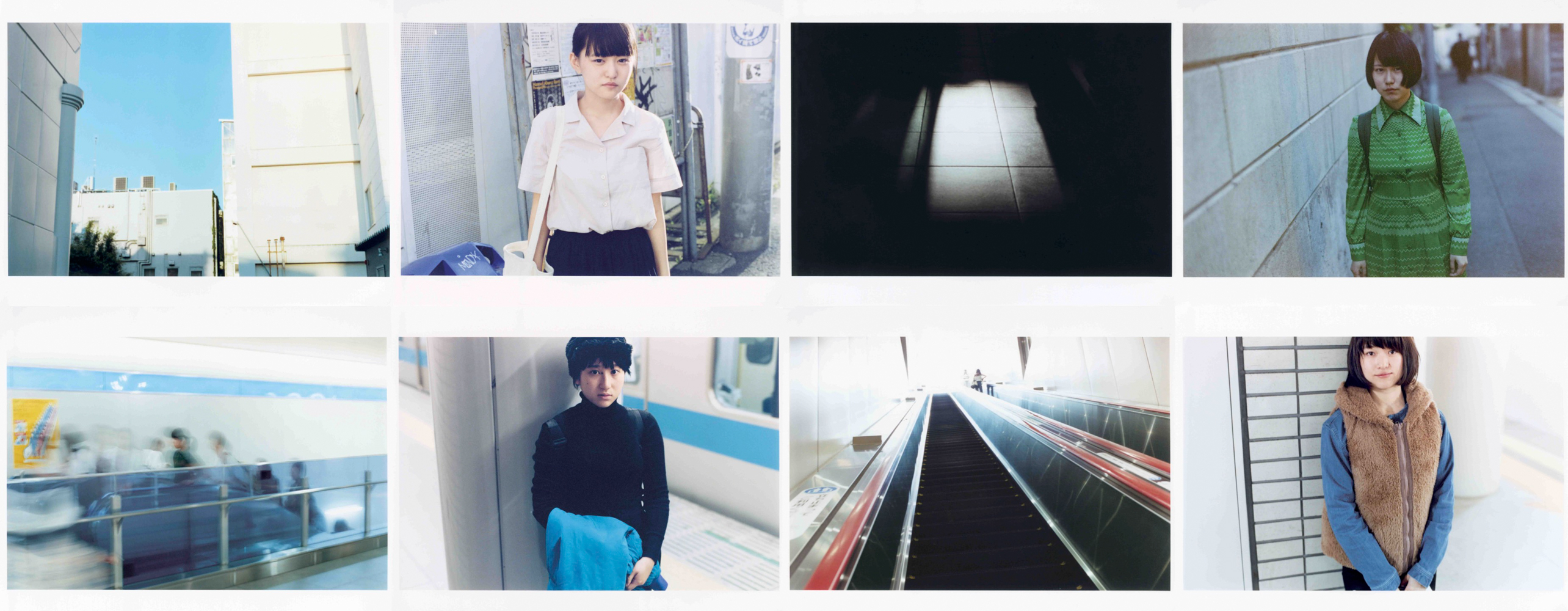

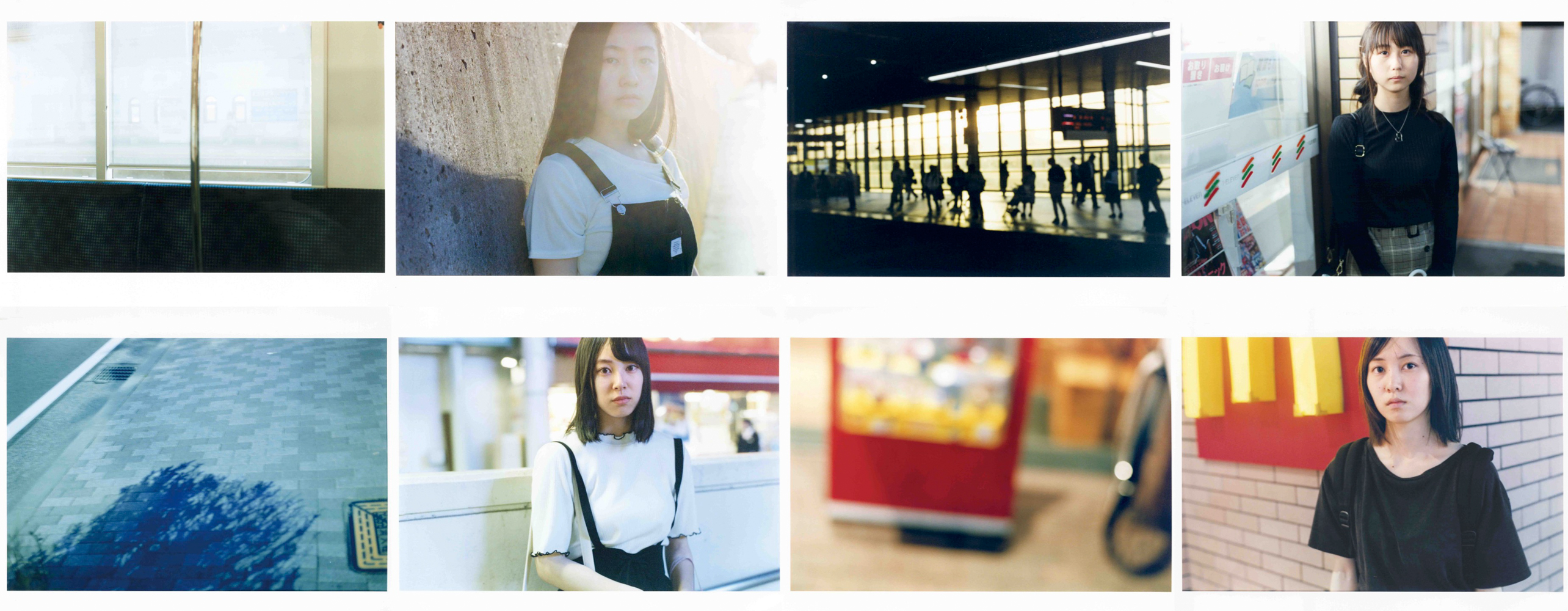

The photographs are arranged horizontally like frames of a movie reel with a typological approach to the portraits and locations. The project speaks to heartbreak and healing after a break-up by looking for faces that reminded him of what he lost. This series began with an encounter in Yoyogi Park, where he approached a solitary woman, asking her if she would let him take her portrait.

After breaking up with his ex-girlfriend in 2006, Morimoto started to go Yoyogi Park in Tokyo and take pictures of the girls with similar characteristics to his ex. Over the years, he has photographed more than 1,000 women. Morimoto eventually ventured beyond Yoyogi Park, encountering people hidden within the forest of the city, capturing both their portraits and the scenes of their surroundings.

He’s single, living in a small house, most of which is used as a darkroom. His bathroom is only for developing film and his fridge merely stores negatives. He wants to heal himself through photography.

Instagram: @morimotoyosuke

Yoyogi Park, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo

I entered a photography school in Tokyo in 2001, but I didn’t know what I actually wanted to photograph. I had a girlfriend I had been dating since high school, but shortly after moving to Tokyo, we broke up. I think I regretted not having taken any photos of her. That might have been why I started photographing women.

The first time I approached someone to take their picture was in Shibuya. It was a school assignment to photograph people there. I approached a man about the same age as me near the scramble crossing, but he refused. Then I spoke to a woman selling hats in front of Marui. Thinking back now, I realize I probably bothered her while she was working, but at the time, I wasn’t that considerate. Still, she let me take her photo. It was already dark by then, and the picture didn’t come out very well.

After graduating, I couldn’t find a job, so I worked part-time at TSUTAYA in Shibuya. On my days off, I would go to Yoyogi Park and approach people for photographs. I often couldn’t gather the courage, so I’d drink a beer in the park before speaking to anyone. Between 2001 and 2004, I was able to photograph about 200 people. Later, I started dating a coworker and began taking pictures of her.

In 2006, I began working at a photo studio in Tokyo that handled fashion and advertising shoots. Staff members used the studio on days off to practice shooting with stylists and makeup artists so they could eventually do those types of shoots professionally. Around the time I started working there, I broke up with my girlfriend, and I began again to go out to the park or the city on my days off to ask people if I could take their photo. The first shoot after that was again in Yoyogi Park.

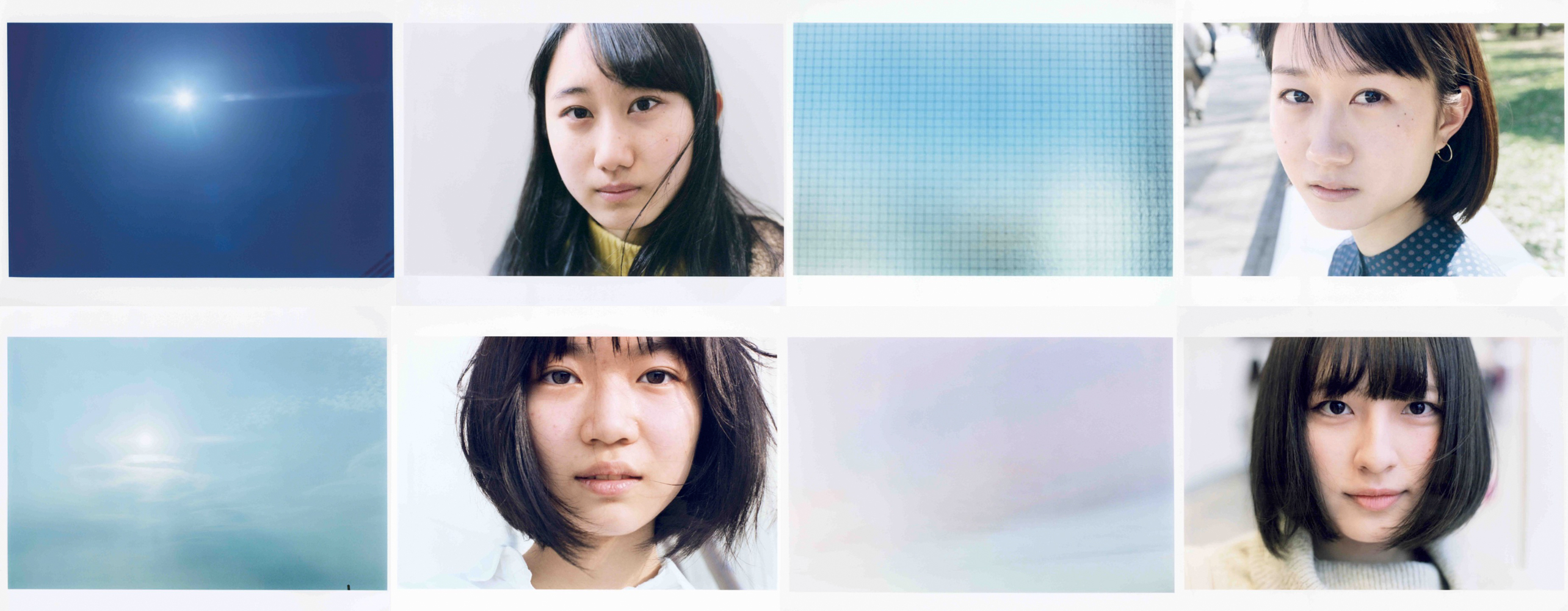

There was a woman drinking Starbucks coffee and listening to music on her iPod. It was a weekday evening, and there was hardly anyone else around. The atmosphere felt a little melancholic. But when I approached her, she said I could take her photo. It may have been cold. I hadn’t had anything to drink, so I couldn’t say anything clever—I just nervously took the photos. I took about five shots, thanked her, and left the park. I don’t think we spoke much. I didn’t even get her name. When I developed the film and made prints, the woman looked sad in the photo. The expressions women show when a stranger photographs them seemed similar to the expression my ex had when we broke up. I had been photographing one person, and when I could no longer do that, maybe I started photographing many people instead. Looking at those photos may have been my way of comforting myself. I once heard that the kind of sadness that hurts the most contains a kind of pure beauty.

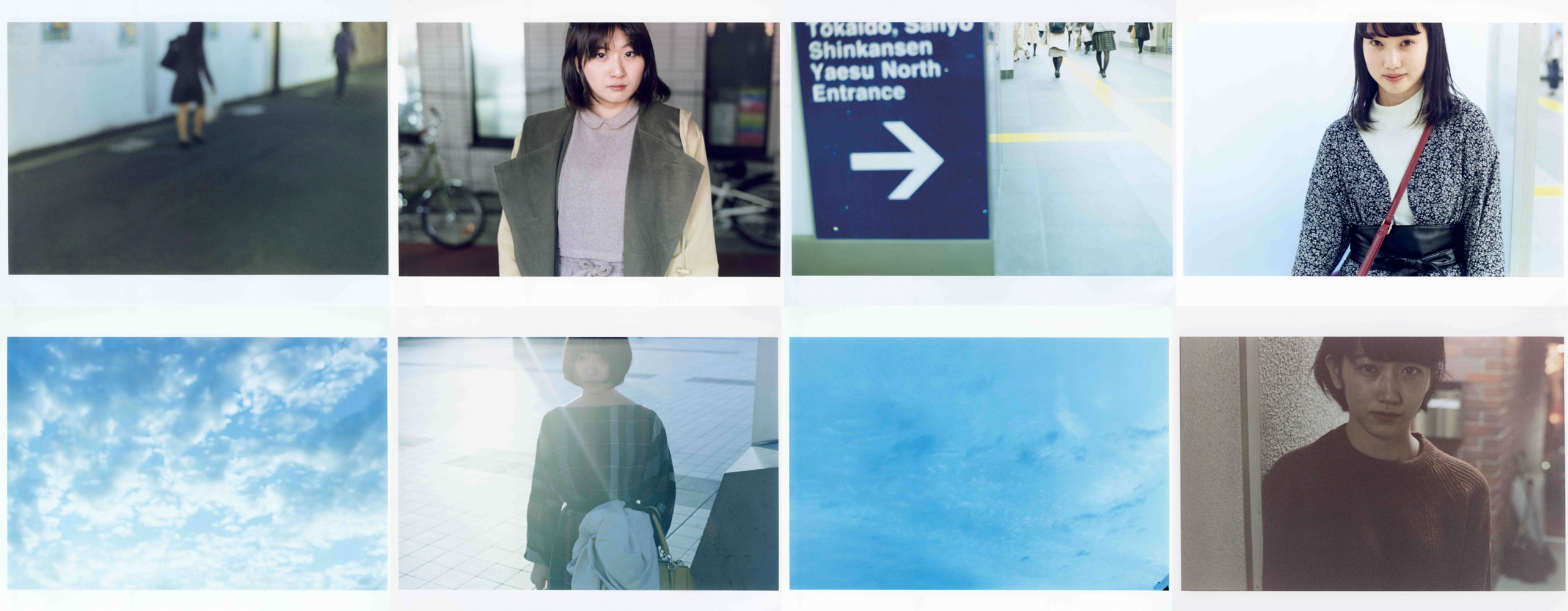

After that, I left the studio and became a photographer’s assistant, and in 2014, I went independent. But I didn’t have much work. Instead, I had a lot of time. Most days, I would leave home in the morning and walk around photographing people until sunset. This photo book contains photos I took between 2006 and 2023. I started in Yoyogi Park, but later moved on to Shibuya, Harajuku, Shinjuku, Ueno, Kichijoji, and Shimokitazawa, photographing more than 1,000 people in total. Originally, I may have been looking for someone to photograph in place of the woman I had lost, but as time passed, I think my reason for going out to shoot changed.

I usually ask, “Can I take your picture?” but most people refuse. Many people in Tokyo live lonely and difficult lives. They don’t talk about it, but I believe many are going through things I couldn’t even imagine. Despite their anxieties, they go to work or school every day. In order to feel safe, people need to think and make decisions. That’s why they don’t want to be photographed by a stranger.

Sometimes, I walk around all day and can’t take a single photo. There are days, three days, a week, even a month when no one agrees. Still, when I keep asking, someone occasionally says, “Are you sure I’m okay?” These women aren’t wondering why I take photos, but why I chose them. Maybe they don’t see their own beauty, or maybe they lack confidence. They don’t even ask me why I want to take their picture. Why is that? Maybe truly beautiful people don’t realize their own beauty. I once read in a novel, “There’s nothing more beautiful than pure emotion. And nothing stronger than something beautiful.”

Once, I was waiting for the elevator at Daikanyama Station when something bumped into me from behind. I turned around and saw a blind woman. She was looking for the ticket gate, so I guided her there. After using the restroom and returning to the ticket gate, I saw her standing there again, outside the gate. Many people were around, but no one seemed to notice. I approached her and guided her a bit more. She asked, “You know this area well. Do you live around here?” I said, “No, but I come often, so I’m familiar with it.” That was all, but somehow, I felt deeply moved—she seemed so dignified. Maybe when I first came to Tokyo, I too was someone beautiful like her. Maybe having nothing I wanted to photograph was, in a way, a blessing. Some people feel compelled to express something even if it doesn’t bring them any reward. And maybe photos help us remember those things.

In the city, everything has a reason, and people seem like they’re always out of time. But being seen as busy might be viewed as a good thing. People who find unstructured time uncomfortable leap from one reason to another to avoid having free time. The city is full of reasons, and the moment we get free time, we jump from social media to videos, games, and news. With no time to spare, we prefer things that are quick and easy to consume. Things without clear reasons make us uneasy, and we can’t bear that anxiety within ourselves, so we try to explain everything—once we understand it, we lose interest. Being approached or approaching someone in the city becomes a source of anxiety. People who only see the surface judge others by how they affect them, not who they are. The more hollow someone feels, the more they try to fill that void, and if what they choose is meaningless, they may be left helpless once they realize it.

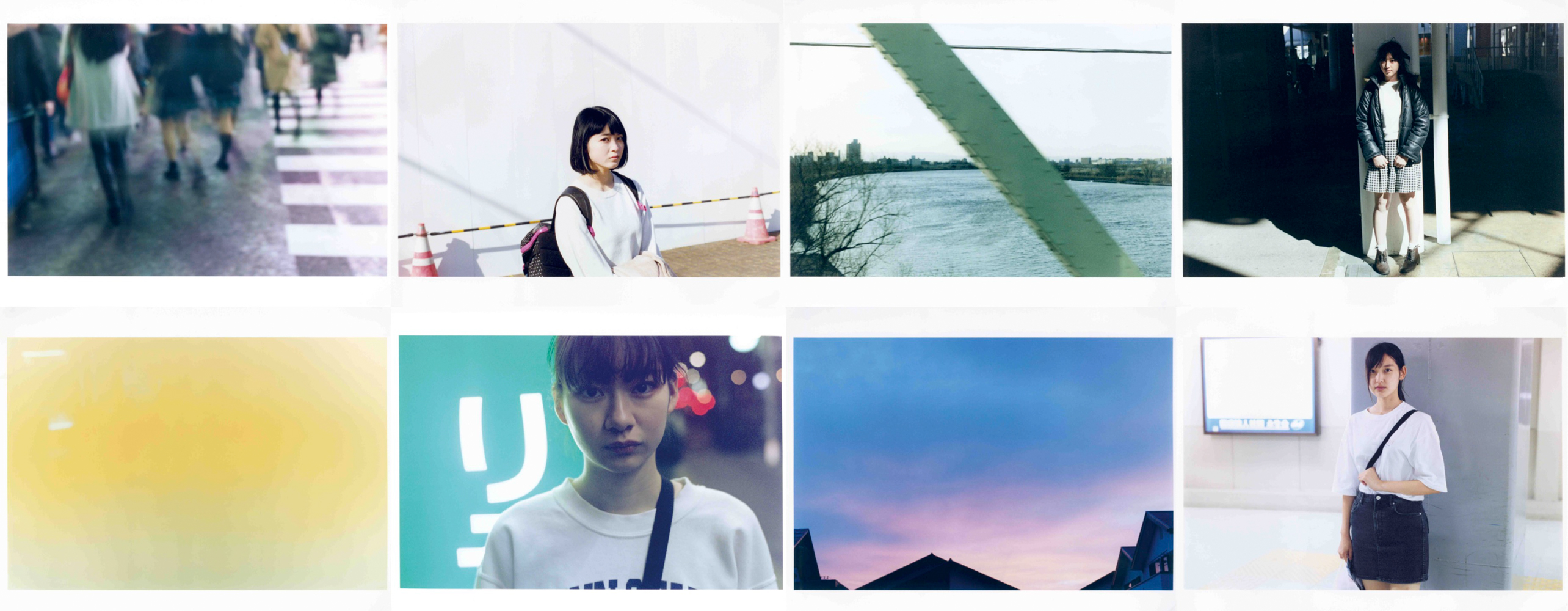

In the park, people were simply spending time as they pleased. Out of kindness, some allowed me to photograph them. Maybe more than getting to take their photo, what made me happiest was their kindness. Even after I started photographing in the city, maybe I was still looking for people like that.

In 2021, I met someone who had come to Tokyo to attend school. They said they hadn’t been able to attend classes yet and hadn’t met anyone. They used to take photos back home and wanted to try shooting in Tokyo but hadn’t had the chance. Another person told me they had developed anxiety from trying too hard to fit in at their high school in Tokyo. They gave up on their original goal and began studying at home to enter a different program. In the end, things didn’t go as planned, but they said they were able to bring it to a close in a way they could accept. That person said they wanted to leave behind a photo of how they looked at that moment, and allowed me to photograph them.

Everyone’s circumstances and feelings are different. No two people in the photos are the same, and yet we tend to look at people as if they are. Not just in photos, but in daily life—we try to categorize and compare: more or less, higher or lower, longer or shorter, faster or slower. We don’t imagine what they think or how they’ve lived. Being constantly seen this way makes people value external judgments and lose sight of what’s important to them.When I exhibited my photos in Kyoto, someone told me, “I like how the photos let me imagine what kind of street this person walks down to get to school or work.” Talking with them, I learned they had a child about the same age, attending school in Tokyo. Maybe seeing the person in the photo made them think of their own child, and even imagine that person’s mother. Very few people see photos that way. But that person, I believe, is able to see people differently—even those they can’t meet in person.

Words try to make everything the same, but our senses capture differences. When you turn your gaze inward to a person’s beauty, sameness disappears, and the irreplaceable nature of each individual can’t be expressed in words. Only a gaze like that can truly face this one, fleeting life we are living right now.

She said she wanted to see the cherry blossoms in Yoyogi Park. She was leaving Tokyo for a while and wanted to see them one last time. When someone tells you they have only a year or six months left, even the cherry blossoms look different. The flowers are the same, but it’s not the blossoms that have changed—it’s you. As you change, the world looks different. And the version of yourself from that moment is already gone. Still, I want to remember how I felt at that time. Even if things don’t go the way I hoped, if I can end things in a way I’m satisfied with, I’d like to believe it made me value the present more deeply.

A month after my grandmother passed away on July 14, 2014, I received a letter from my uncle. In it, he wrote that my grandfather had disappeared after leaving to work in Tokyo when my uncle was in the third grade. Since then, my grandmother had endured a life of hardships she couldn’t speak about openly.

After I moved to Tokyo, my grandmother and mother would often check in on me, sending money and calling frequently. Perhaps their concern came from that family history. For me, it was truly a lifeline. Without their support, I don’t think I could have stayed in Tokyo. It gave me the motivation to try and make something of myself. But even now, I feel like I haven’t accomplished anything meaningful yet.

If this photo book were to be released on the anniversary of my grandmother’s passing, I don’t think she would be pleased. She wasn’t someone who ever wanted attention for herself. But my mother and uncle would be happy, and if they’re happy, then I believe my grandmother would feel happy too.

Everyone who allowed me to take their photo has a mother—and a grandmother. Without a grandmother, there would be no mother, and without a mother, that person wouldn’t exist. Someday, that person might become a mother, and perhaps even a grandmother themselves.

That’s why I felt that the anniversary of my grandmother’s passing was the right day to release this book.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026