Overshoot #6 with Siobhan Angus

In the winter of 2024, I poured myself into Camera Geologica, Siobhan Angus’ brilliant book, in which she unearths the extractive history of photography.

Dematerialization has become a touchstone word to describe our digital world and experience today. Photography isn’t exempt from this description. For many, digital photography is a hallmark of dematerialization. In addition, all the digital tools we use are often described as dematerialized, as though they had become weightless. The digital experience itself seems to corroborate this: storing files on the cloud, switching between tasks and applications feels frictionless, and the tiniest storage devices can carry dozens of thousands of high-resolution images.

However, dematerialization is another word for externalization. Navigating the digital world feels weightless and frictionless because high-power machines outside of our immediate vicinity process, store, and disseminate untold amounts of data. In 2017, the International Enegery Agency released a report called “Digitalization and Energy” in which our entry into the “Zettabyte Era” is thoroughly analyzed. Global annual internet traffic has seen an exponential increase in the past 15 years and the advent of mass-produced connected devices. Phones equipped with high-resolution cameras are perhaps the most iconic items of these.

Angus’ richly-layered inquiry foregrounds what’s elemental in photography: bitumen, silver, platinum, and rare earth metals; drawing a historical arc that traverses the past 180 years and persists in the present. Furthermore, Angus finely examines the conceptual frameworks that accompanied the birth of photography in 1839, namely the enduring idea that photography promised a divorce between representation and the limitations of matter and space, as she writes in the introduction. And in fact, photography has convincingly produced a visual divorce between image production and consumption. However, as Angus shows, this divorce was only made possible through extraction. In other words, weightlessness astutely disguises the dirty, dusty, noisy, distant, and energy-intensive processes that make photography a well-oiled machine.

In the interview below, one of Angus’ responses has been staying with me: “Asking a different set of questions about photography enables us to ask a different set of questions about our world. In our current moment, that feels like a pretty urgent task.”

Yogan Muller: Your recent book, Camera Geologica, a richly layered inquiry into photography’s materiality, was published by Duke University Press last year. What initially compelled you to research and write this elemental history of photography?

Siobhan Angus: It started out through research on mining. I did my training in labor history and became interested in the foundational role extraction plays in our lives. I took a class on images as history, so I started thinking about this connection between the mine and the photograph. This very material link. One of the things I’ve always been interested in is what lies in plain sight but doesn’t get attention. One thing we hear a lot about extraction is that it’s hidden. You live in LA, right? There’s oil infrastructure all around the city. In many ways, these things are not hidden at all. We just don’t notice them. Why do we choose not to integrate this into active consciousness?

When we think about the photograph, we have these fantasies and narratives of immateriality, dematerialization, lightness, that we see in an extreme form today with generative AI, the “cloud,” and the digital image. These fantasies go back to the origins of photography. At the same time, photography’s materiality and process are always hyper visible: the silver gelatin print, the platinum print, the silver screen, and now paper, printers, computers, servers, etc. In many ways, the photographic object itself is always signaling its material connection and heaviness, but we ignore it. That tension struck me as really interesting.

Photography is a very useful lens to think through this broader problem of extraction and how we bring into visibility and public discussion things that we don’t like to think about.

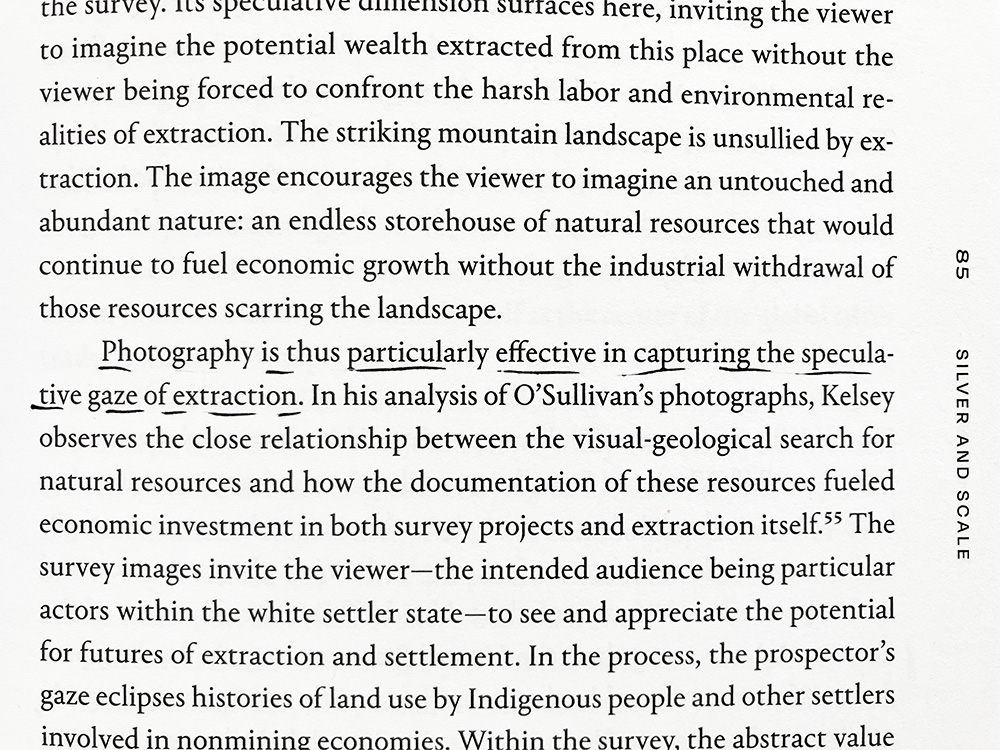

Passage in Siobhan Angus’ Camera Geologica, Chapter 1, p. 85.

I do think that it’s artists and artworks that can do that in the most effective way. As I was starting to work on the project, Camera Geologica was a purely archival history looking at silver mining. However, as I was writing, I found myself running into the contradictions we’ve just discussed. It was meeting a few artists who work with material-based processes and then talking to them about their practices that really changed my understanding of how extraction functioned, but also what photographs and artworks can do to make it tangible.

My project evolved into thinking about photography in a multifaceted or almost kaleidoscopic way, insisting on how images and materials come together to reveal and simultaneously shroud our world’s inner workings.

YM: Central to your book is the reckoning of photography’s extractive nature. You wrote a counter-history of sorts because up until very recently, we’ve convinced ourselves that photography is an instantaneous, at-no-cost, frictionless act, when in reality, it always rests on a global network of operators, industries, and resources.

SA: It’s interesting to me why we want things to be weightless and why we want them to have no cost. That is the question that I find really compelling because, if you talk to practitioners, they will tell you at length about the entangled, material, elemental connections: working in the dark room, color correcting images coming out of the printer, experimenting with different materials, etc. Right here, we see another parallel to mining. Those are two industries where people are in really close proximity to various forms of chemicals and other pollutants that enter into the body. It’s this very entangled, labor-intensive history. And yet, we love to think about photography as “the agency of light alone” to borrow Talbot’s phrase. Throughout the history of photography, there’s this push and pull between the rhetoric of instantaneous, cost-free image replication; and, on the other hand, the very material and embodied history that runs beneath it, which sometimes comes into visibility.

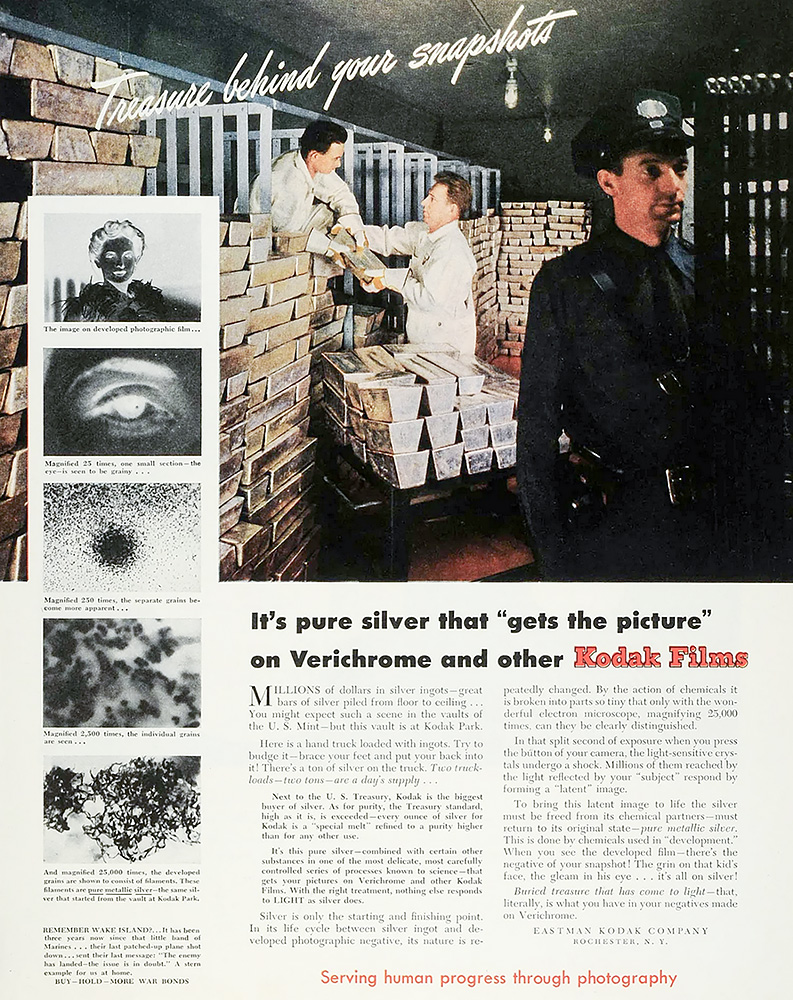

It’s pure

It’s pure silver that gets the picture, on Verichrome and other Kodak Films, Ad, reproduced in Life, January 15, 1945

If we foreground process and materials, there are radical implications for how we think about photography, which, in turn, centers photography as a medium that’s deeply enmeshed in the world. In other words, asking a different set of questions about photography enables us to ask a different set of questions about our world. In our current moment, that feels like a pretty urgent task.

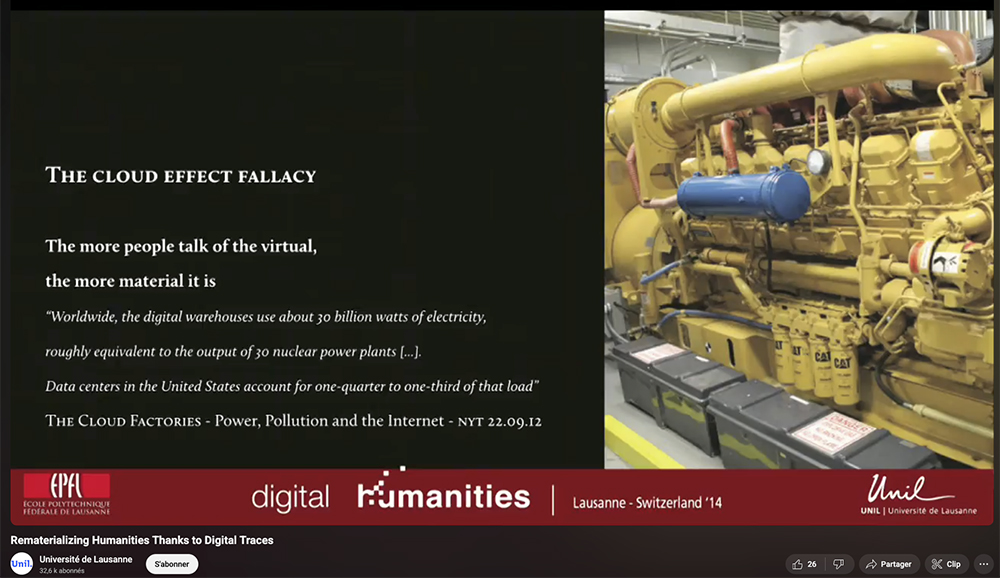

YM: Preparing our conversation, I remembered a quote from the late Bruno Lour, who, in a lecture he gave in Switzerland in 2014, observed: “When we move from the real to the digital, we’re moving from the real to the more real, from the expensive to the more expensive, from the down to earth to the even more down to earth.” It seems to me that digital photography suffers from the same disconnect. And this is where your work is critical because it traces energy, material, and mineral flows across space and time.

A slide from Bruno Latour’s lecture “Rematerializing Humanities Thanks to Digital Traces,” Université de Lausanne, Switzerland, 2014. https://youtu.be/4L2zRoKS0IA?si=alfguy8wiojv8LgD&t=2603

SA: That’s such an amazing quote, and I wish I’d included it in the book. The digital is so material-intensive: it’s estimated that 84% of the stable elements on the periodic table go into every smartphone. The vast majority of those materials can’t be recycled even if they enter into a closed-loop system. When we think about digital images, they flicker on our screens and then suddenly disappear, which makes them seem immaterial. Simultaneously, we see devices getting smaller and smaller. But the way they become smaller is through mineral intensiveness. Bulkier components, such as plastics, have been replaced by rare earth elements, coltan, or tin, entangling distant geographies and many forms of extraction, many of which are incredibly harmful. All forms of mining have violence, but some forms of mining have more violence. A lot of the technology metals are extremely difficult to extract and process. And then they enter into these systems of e-waste, which replicate neo-colonial violence of extracting minerals, often from the Global South, and then returning the waste there to be burnt or salvaged for scrap. As we reckon with climate and environmental justice, acknowledging the cost of the digital world is really important.

We still see those email signatures that invite us not to print the message to save paper. And that’s true in some ways, but the fossil fuel infrastructure that powers the cloud, the water that goes into data centers, are some of the gluttonous nodes and moments that we need to consider as well when sending emails. It’s useful to retrace this technological chain because, suddenly, we can see all the different places where we can intervene. There are many small tweaks or ways we can close loops or move towards more sustainable practices that are, in fact, quite doable if we had more political will. They’re hard to scale up on an individual level, but they’re possible to consider on a collective scale.

These questions are urgent with the rapid expansion of generative AI, which is incredibly materials-intensive. One of the things that we’ve seen is the opening of new nuclear power plants to meet the energy needs of generative AI, and I think what this highlights is that we need to be having collective conversations about what we prioritize, how we use these technologies, and how we can think about making them more sustainable.

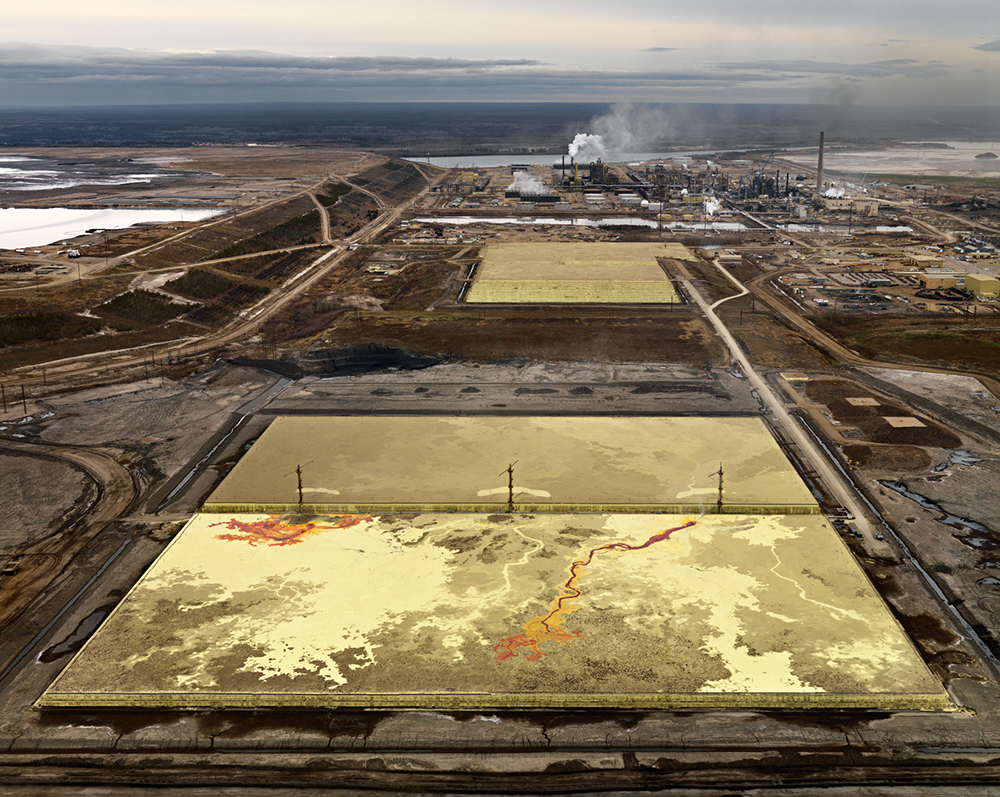

Edward Burtynsky, Alberta Oil Sands #6, Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada, 2007. Inkjet print. © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto.

YM: Earlier in our conversation, you mentioned the early days of photography, and I’d like to go back, for a brief moment, to the mid-19th century when photography became more and more popular and widely used. There’s a quote – you discuss in your introduction – from Oliver Wendell-Holmes, who noted in 1851: “Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing taken from different points of view and that is all we want of it,” before adding, “Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear, form is cheap and transportable.” In France, in 1852, Etienne Louis de Cormenin, an industrialist who promoted and pushed new, faster photographic processes, wrote strikingly similar lines: “Heliography will go around the world for us, and retrieve the universe in a portfolio while we sit in our armchair.” Both propositions are chilling, obviously, with their extractive, imperial, and colonial undertones. You show in your book, on the other hand, that form has never been cheap because it has always rested on the extraction, global circulation, and processing of ores. Is it fair to say that photography kind of catalyzed this divorce between matter and form, to quote Wendell-Holmes back?

SA: I think so. It’s tantamount to this broader desire running through capitalist and colonial societies that you can accumulate endlessly at no cost. Photography seems to make that possible. Of course, so many things have to be ignored for that fantasy to seem true. A few years after his 1851 article, Wendell-Holmes visits a photography supply factory and tells us: ten tons of silver were used in one factory while millions of eggs are used to make albumen prints. It’s these incredible numbers and scales. Mind you, he made this remark in 1863, so it was still relatively early in the history of photography. By the 20th century, the scale is absolutely immense–photography becomes the biggest use of silver besides the mint, drawing up to 25% of global silver supplies–and Kodak becomes the largest polluter in New York state. Yet, this fantasy that we can divorce form from matter is a really powerful and enduring one.

One of the things that felt important in writing the book was to not just write about materiality and make statements such as “this is the amount of silver used,” or “this is where it came from,” but also to take form and representation seriously, as doing entangled and sometimes different work. In art history, we sometimes feel the need to separate form and material quite strictly. They’re always completely entangled. The form you choose determines representational possibilities. People playing with representation can also innovate new ways of working with materials and materiality. For me, bringing those two things back together conceptually also felt important because, as much as we know those quotes by Wendell-Holmes are terrible and rooted in something that we would reject, that line of thinking is deeply ingrained in the way we’re taught to think about both images and the world. So, doing the messier work of putting things back together and seeing what emerges is a way of letting contradictions appear and crack apart.

Such material contradictions are the brutal specificity of how our world is made, and is something that, I feel, capitalism and colonialism do a lot to efface. There’s that great Rob Nixon quote that capitalism abstracts in order to extract. Hence, doing something as simple as taking a particular object and then tracing all of the different materials that come into it, the different histories that surface, etc., is a way of doing some of that reconnecting work that goes against the severing and siloing that allows us to continue to enact these incredible forms of violence that make extractivism possible.

YM: I just love how the conversation is flowing. It brings us to the gap that your book bridges between the visual and the material. The former is, in many respects, central to our culture, while the latter is relegated or made invisible, as you just observed. However, the carefully chosen artworks you discuss in your book unravel the metabolic relationships that exist between photography, the mining industry, and the biosphere. Please tell us about the iconography of Camera Geologica and how you assembled it.

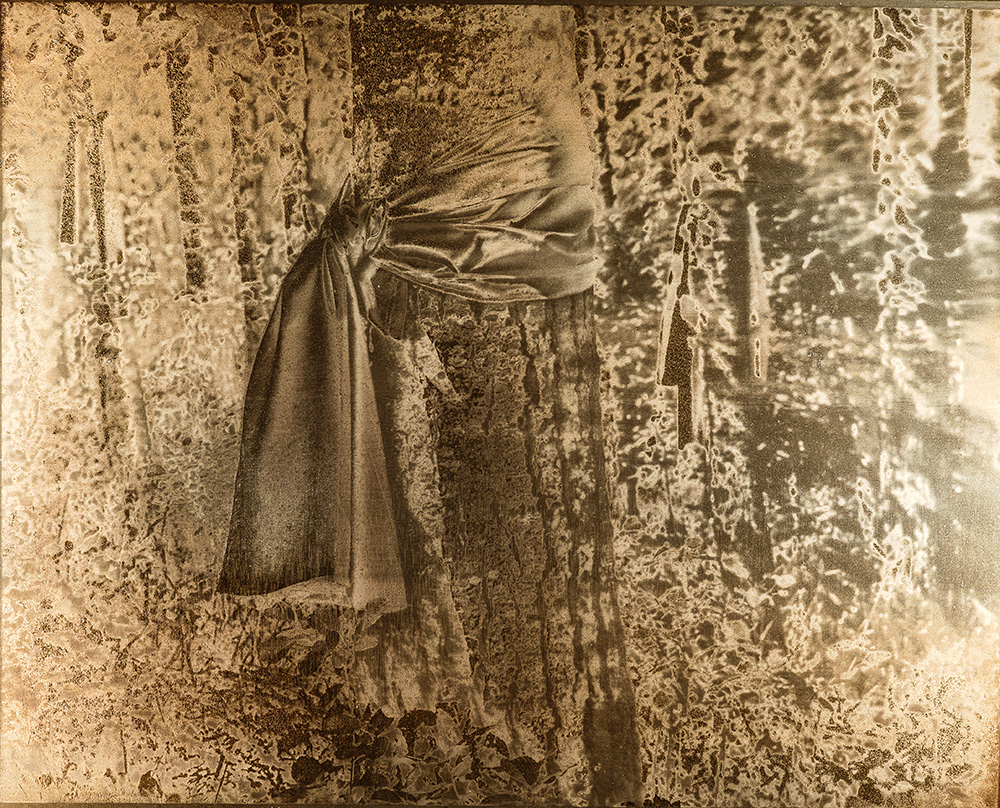

SA: I love this question. When people hear about my book, they assume there’s a suspicion of the visual or representation. I don’t feel that way at all. I love photography in both its material process, its physical forms, but also in what images, iconography, and symbolism can tell us. In many ways, the argumentative thrust of the book – or the theoretical underpinnings – came from the artist projects I engaged with, and in particular Warren Cariou, whose work is reproduced and discussed in chapter 1. He makes these bitumen photographs from the Athabasca tar sands region in Canada. It was through conversing with Warren over several years that my thinking about extraction, alongside what the visual can do in that context, really changed.

Warren Cariou, Prayer Tree, 2017. 8″x10,” petrograph on aluminum. Courtesy of the artist.

Each chapter begins with a contemporary artist project that examines the relationship between the visual and the material, making the contradictions and tensions we previously discussed palpable.

Moving between these different material processes, which have very different visual histories, extractive histories, political formations, and timelines, was a way of introducing a productive set of tensions. How these contemporary artists were reactivating these histories and why they were returning to these older processes was another way of thinking through the way that the past is active in the present as a shaping force. This moving back and forth between the 19th century and the 21st century was a way of trying to think about how all of these incredible world historical transformations, that are set in motion in the 19th century, echo into the present, sometimes in very literal ways and sometimes in more symbolic or suggestive ways. It was also interesting to me how many contemporary artists are returning to the 19th century to think through the present.

Photography is an interesting medium for achieving that because of its uniquely privileged relationship to time. Photography looks at that which exists in the present but is always looking backwards and, in many ways, also always forwards. Hence, thinking through those artist projects was a way of mapping out the complex temporalities the climate crisis has introduced and a way of entangling both geographies and material histories, but also temporalities.

Louis-Jacque-Mandé Daguerre, Shells and Fossils, 1839, Daguerreotype.

YM: How was your book received, and have you seen a growing interest in researching photography’s material footprint among our global academic peers and colleagues?

SA: There are a lot of artists and practitioners who have been thinking through these questions for a very long time in a lot of different ways. For example, some of the artists in the book return to the photographic materials that cause harm, while others are spearheading the rise of the sustainable darkroom movement. Here, though, I don’t want to set up a binary between certain forms of material process and people working with digital or silver gelatin prints because I definitely don’t think that there’s one aesthetic strategy that is more effective or one material strategy that is less harmful. The ethics of representation and how other technological histories of the medium surface today also feed into this conversation. It’s really exciting to see how many people are approaching photography’s material histories, its chemical histories, and its imperial histories by asking a different set of questions. However, I do think that, in many ways, it is artists who are leading this conversation.

The other way to answer your question is to return to the Latour quote. I think there is a profound desire to ground things back in the real. We have this narrative of the move towards a “hyper reality” and, at the same time, the incredible escalation in what that means in terms of concrete, material realities. More and more people are starting to critically examine this dichotomy because it’s one of the push-pull tensions of our present moment.

YM: What does photographing in a warming world mean to you?

SA: Good question. Obviously, I love photography. I am deeply invested in it. Sometimes people hear the material analysis, and the takeaway is that we should take fewer photographs or that photography is somehow harmful. I would never want that to be the takeaway from the book. If we’re going to use materials like silver for anything, I think we should use them to create meaning, to help us understand our world, to connect, to illuminate. It’s important to maintain that critical lens and critically reflect on what images do, why we take them, and what work we ask them to do.

We’re in this strange historical moment where, in many ways, we know what we need to do, but there’s no political will to do it. We struggle with imagining how we’ll make the energy and material transitions that we know are necessary. What art does in its best forms is connect us more deeply to how we feel. It opens up this other, more imaginative, more affective space for reflection. And many photographers have their practice rooted in research which introduces all kinds of complexity to public debate that can allow us to inquire about histories that we’re often aware of but are reluctant to think about.

Artists and photographers play a central role in helping us understand how we’ll traverse the climatic transitions because one of the key questions is: we can’t visualize, let alone embrace, these transitions until we shift what we value. Here, art is a powerful way of opening new pathways to valuing things and forging new narrative approaches, new emotional entanglements with the world, and subsequently, new stories.

It feels urgent that people make as much art as possible. For example, in the context of documentary photography, bringing sites into visibility, or playing and researching processes and materials, is really important.

A multiscalar challenge like climate change requires many different approaches. Sometimes in the arts, we can feel like we’re not doing the important work, which would be environmental policy or science, but, actually, the arts and the humanities and any critical discourse help us get closer to all those climatic goals because they show us possible pathways forward, which, at this moment in time, feel very foreclosed.

Biosketch: Siobhan Angus is Assistant Professor at Carleton University, Toronto, Canada. Her work sits at the intersections of art history, media studies, and the environmental humanities. Prior to joining Carleton, Angus was the Banting Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Art at Yale University. Trained as an art historian, she holds a Ph.D. in Art History and Visual Culture from York University, where her award-winning dissertation analyzed how photography and landscape painting chronicled, celebrated, and challenged the transformations enacted by extractive capitalism and settler colonialism on the Canadian Shield. Her dissertation was awarded the Governor General’s Gold Medal.

Her research has been supported by the American Philosophical Society, the Council for Canadian American Relations, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada, the Science History Institute, the Yale Center for British Art, and the Paul Mellon Centre. Angus is a board member of the Workers Arts and Heritage Center and sits on the advisory board of the Intersecting Energy Cultures Working Group. At the heart of her research program lies an intellectual and political commitment to environmental, economic, and social justice.

Webpage: https://carleton.ca/sjc/profile/siobhan-angus/

Socials: https://www.instagram.com/siobhan.angus/

Order Camera Geologica: https://www.dukeupress.edu/camera-geologica

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Overshoot #9: Liz Miller KovacsDecember 13th, 2025

-

Overshoot #8 – Arturo SotoNovember 15th, 2025

-

Overshoot #7 with Ayda GragossianOctober 11th, 2025

-

Overshoot #6 with Siobhan AngusSeptember 13th, 2025

-

Overshoot #5 – Alex Turner’s “Blind Forest”August 9th, 2025