Portuguese Week: Maria Oliveira

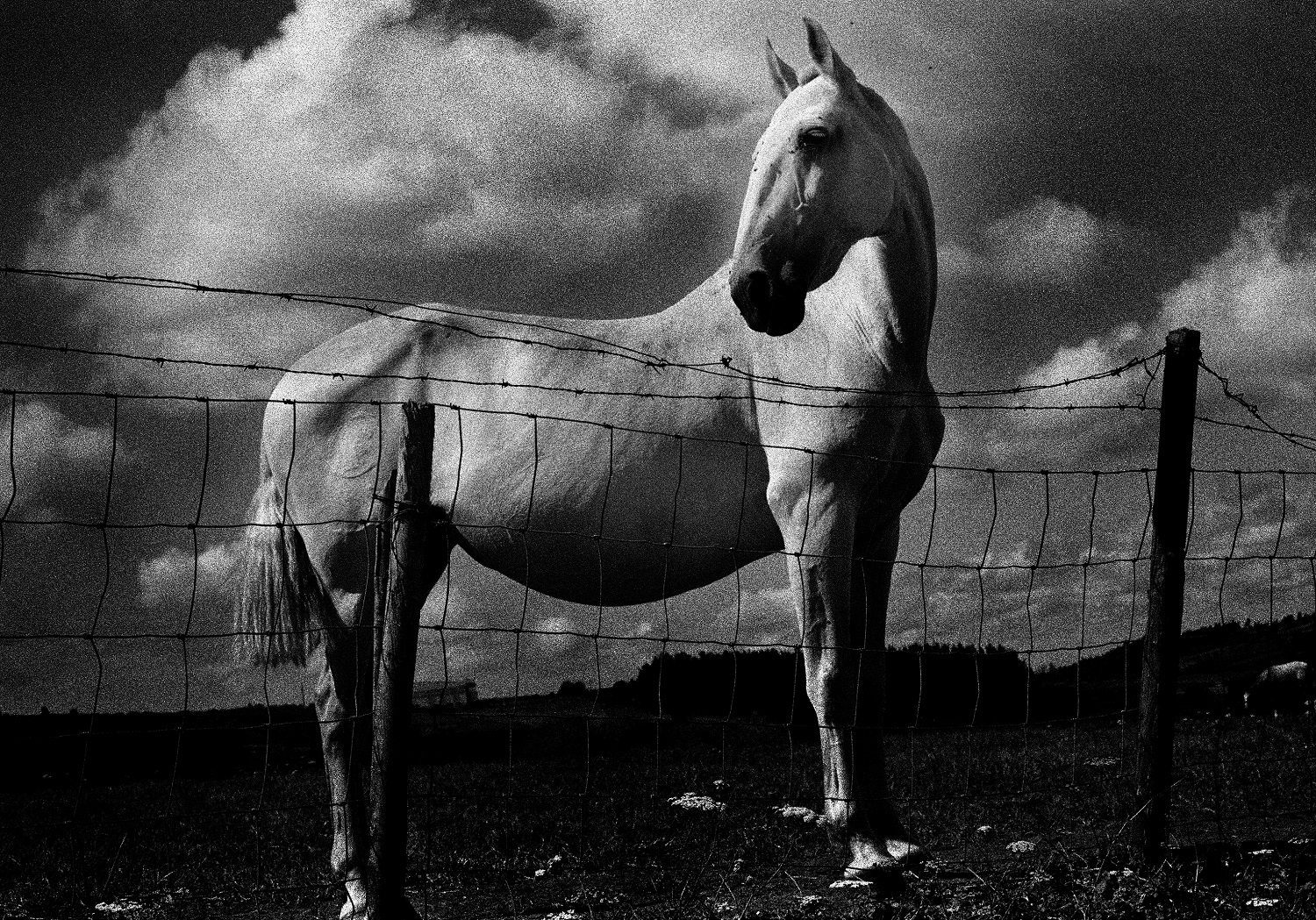

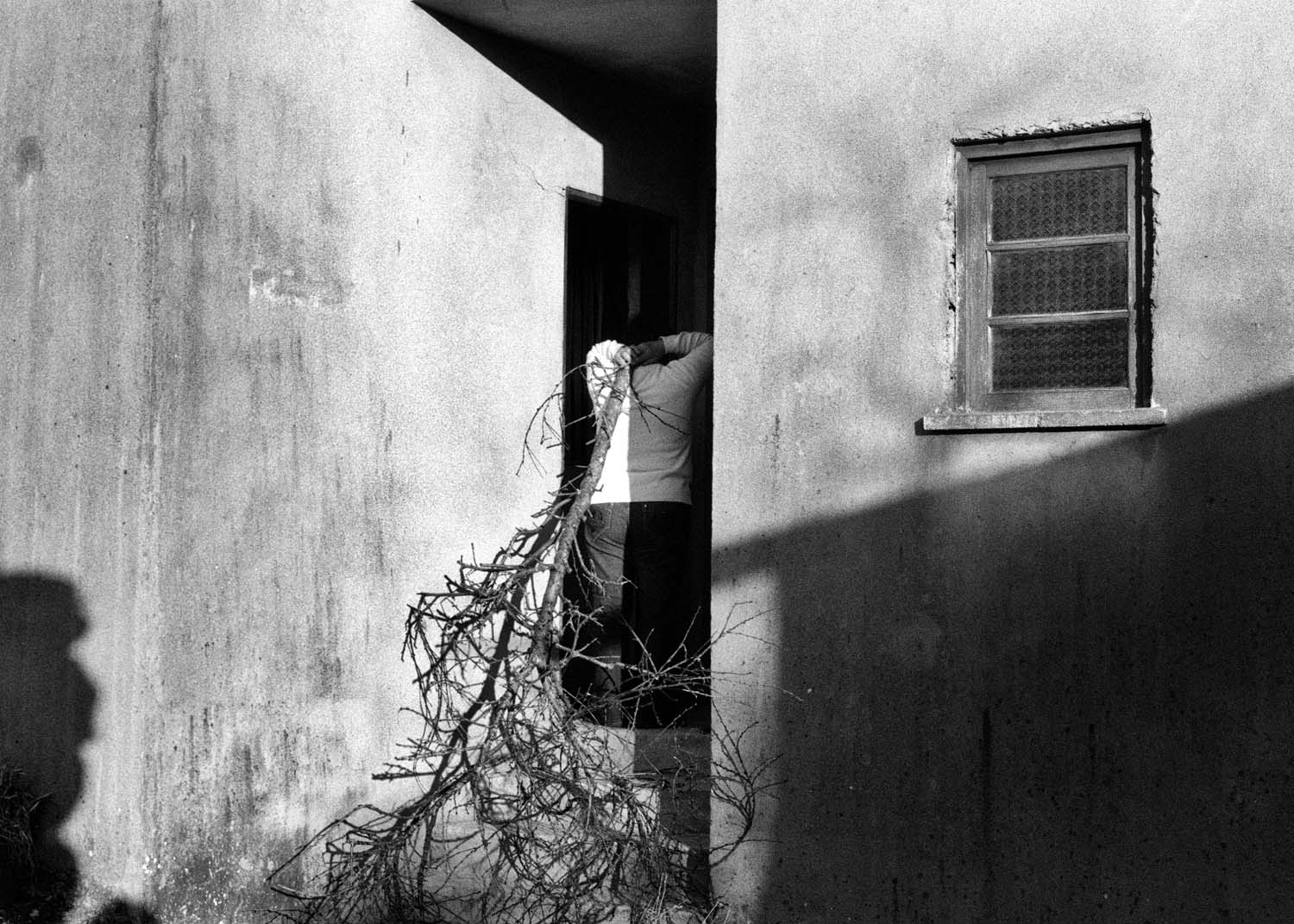

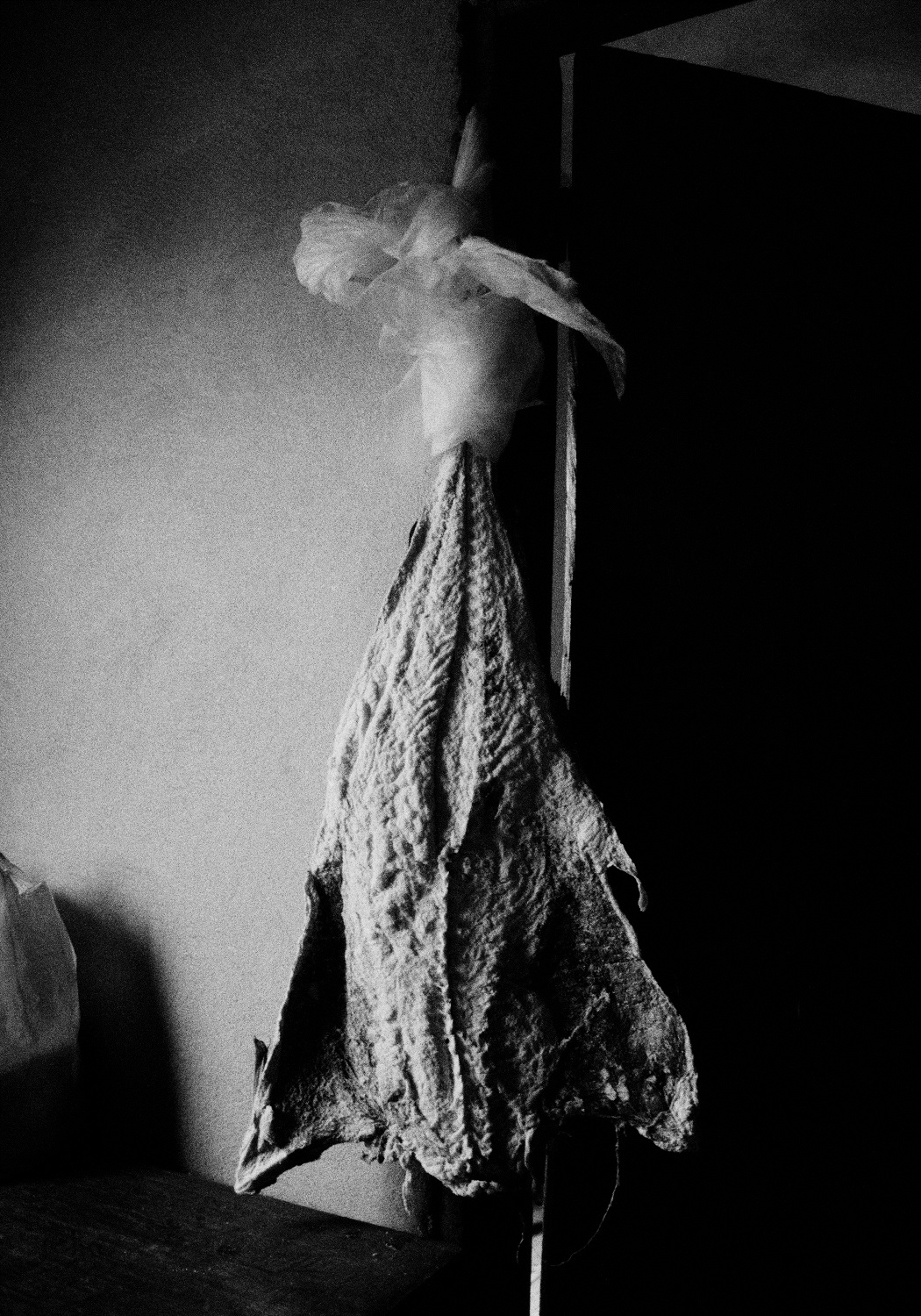

© Maria Oliveira, “Under the Surveillance of Ancient Animals”

The act of selecting or choosing a set of people or works for a specific purpose can be quite a demanding task. Even more so, in my perspective, when it comes to photography. Who are your favorite photographers? Why them? In what stage of their career are they? Fairness is often a criteria that most probably is not fully attained. However, when I was invited to organize a Portuguese Week on Lenscratch, I couldn’t help but to be proud and happy to show some of the best photography being produced these days by Portuguese photographers. And, of course, to use their thoughts and their works to speak about my country or the countries they live in. The artists featured this week show the most visible part of a territory known as Portugal, in all of its contradictions, differences, and similarities, but also a specific mindset. After all, ways of seeing and interpreting the world are without a doubt embedded in a wider system or, as sociologist and visual culture expert Chris Jenks writes, “the way we think about the way that we think in Western culture is guided by a visual paradigm.” In that sense, what are its characteristics? What are the variations of this visual paradigm? To what extent is Portuguese photography or photographers different from any other? The ones gathered for this week portray a specific country, but also other realities with a paradigm based in the adoption, or rejection, of what “Portuguese culture” is. I sincerely hope you enjoy the next week, and feel free to ask questions or share your thoughts on the works. Thank you for being there with us!

The first work I bring is from artist Maria Oliveira. I got to know it while I was living in Rio de Janeiro, back in 2014. During FotoRio, I saw an exhibition titled Under the Surveillance of Ancient Animals, and it caught my eye for several reasons. Most of all, it was the first time I’d seen an exhibition that reminded me so much of rural Portugal. Not Lisbon, nor Porto, Coimbra, or Algarve, but the interior north of the country, the region of mountains, rocks, animals, cold, myths, forests, and, most of all, different conceptions of time. It’s the place where Maria grew up, and where comfort and memory play a tremendously important role. To better understand Maria’s work, I did an interview with her. These are her words.

CB: Your relationship with nature is very intense. An immensity that in a way is also surrounded by memory, by mountains, by time. But also the smell of smoke from the house in winter, an attention towards animals. It does not seem to me to be a “use” of nature- understood as an exploitation- but more as, on the one hand, its need, and on the other, its slow, careful, and respectful observation and company. Furthermore, there is a certain melancholy, a nostalgia for the present time that we already miss. It seems that sometimes we are already in the future, as when we think about our memories and do not see ourselves in the first person, but as if we were observing ourselves from a distance. Can you comment on these two factors?

MO: I think I was deeply affected by growing up in this place, an empty place, crushed by the presence of the surrounding hills, and it was only when I left and there was a rupture that I realized that. It was necessary to leave. Now I understand where things are coming from. This relationship with nature. Time is indeed an important issue. The relationship with time is totally different, the passage of the day is perceived by the difference in sunlight. Things that the city does not allow, or does not give room for them. And, of course, life is much more oriented by the rhythms of nature, the schedules, which is done on a certain day, at a certain time of the year.

MO: In this case, I think that there is no real exploitation of nature, although the relationship is very utilitarian, with animals as well. But I think that there is also a care and respect, yes. Perhaps that comes from this close coexistence, from intimacy. The fields, for example, they are more than land. As they pass from generation to generation they have an associated memory. Somehow, they are part of the family.

On the question of nostalgia / melancholy, I think it is naturally inherent in these silenced, quiet and unoccupied places. When you remove the distractions, the stimuli and remain in this unprotected contact with the most primordial world, a certain state of introspection or at least more accessible is latent. Daily life itself is very meditative, because work is physical, requires time, repetition and is often lonely. So it seems to me that it is easier to be in real time, because there are not a thousand things happening simultaneously, pulling us into the past or the future. I do not say that it is better or worse than any other place, it is a way of being in the world.

CB: Going through your website, I also came across your written essays that, personally, I found charming. A kind of fables, fiction and reality, or a more inclusive reality, in that sense. What is the role of writing in your photography?

MO: I started by writing before shooting. It was the first way to relate to the world, perhaps. Nothing serious or strict, but it stayed. I think of it as a kind of support for photography. In fact, for me, it is much the same, but writing is to keep me company.

CB: Where do your work starts? Autobiographical, certainly, but are you looking for its extension?

MO: I tend to work on subjects with which I am intimate, but I do not intend that the work is limited to this personal relationship. I think that despite these autobiographical references, there is also a certain universality that interests me. Photos are from one place, but that place is not important, as it can be copied to multiple locations and still make sense.

CB: Is there anything like “Portuguese photography”?

MO: I don’t know how to answer that, but I don’t think so.

CB: Lastly, what does your future look like as a photographer, and also for Portuguese photography, or photography in Portugal?

MO: Well, I don’t know much about the future. I do know that I want to keep working and have opportunities to do it. To continue the Bone Foam project and also to develop new projects. I don’t have a very specific idea about Portuguese photography. I can say that I like what I see in Porto, which is the reality that I know best. There are several spaces and events dedicated to photography in Porto these days, such as the Bienal de Fotografia, the Month of Image, The Cave Photography, or Salud au Monde, among others. It seems to me that there is a desire for photography to have a presence in the city and reach people, and that is positive.

Maria Oliveira was born in Ponte de Lima (1982) and currently lives in Porto, Portugal. Based on her experiences, she has been interested in developing works that cover these umbilical, physical and mental places. Because of their mutation, because of the relationships between people and nature, in close coexistence. She is not interested in her documentation, but in a poetic perspective, between the visible and the hidden. Between reality, memory and imagination. She has exhibited regularly, since 2011, in Portugal and abroad. In 2020, she obtained the “Sustentar” Breeding Scholarship, Figueira da Foz Municipality, and in 2019 she participated in the first Port Photography Biennial. Between 2016 and 2017, she was a resident artist of Ci.clo – Photography Platform, where she developed the project Saving Fire for Darker Days, which integrates a patent exhibition in different places, such as Centro Português de Fotografia, in Porto, Portugal; Fotofestiwal, in Lodz, Poland; and the School of Visual Arts, in New York, USA. In 2014, she exhibited at the FotoRio Festival, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and in 2011 at the Casa de Portugal in Macau. In 2019, she was the winner of the FNAC New Talents Award and the Scopio Magazine International Photobook Contest.

Follow her on Instagram: @maria.o.rodrigues

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026