Mexican Week: Margot Kalach — Part I

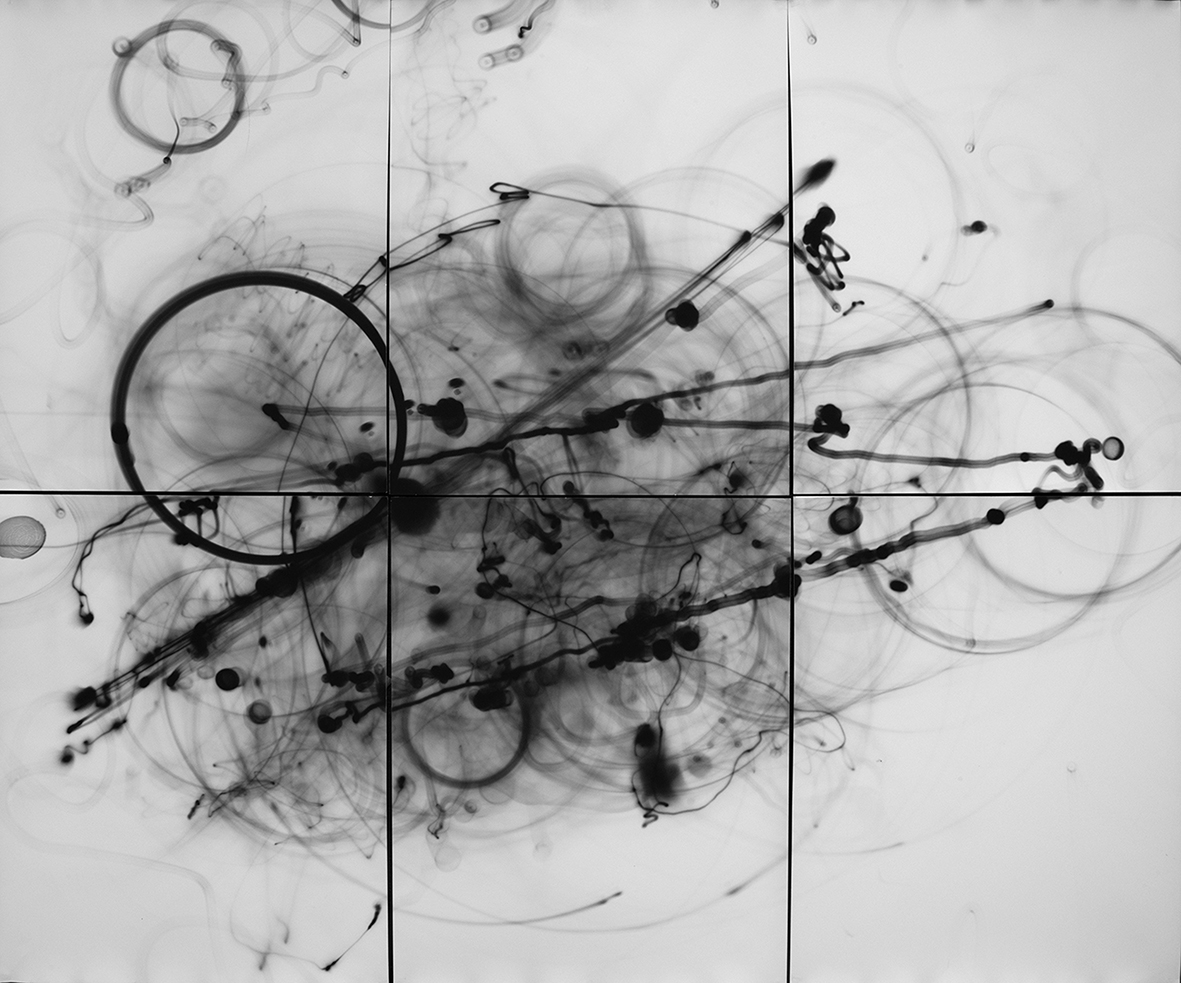

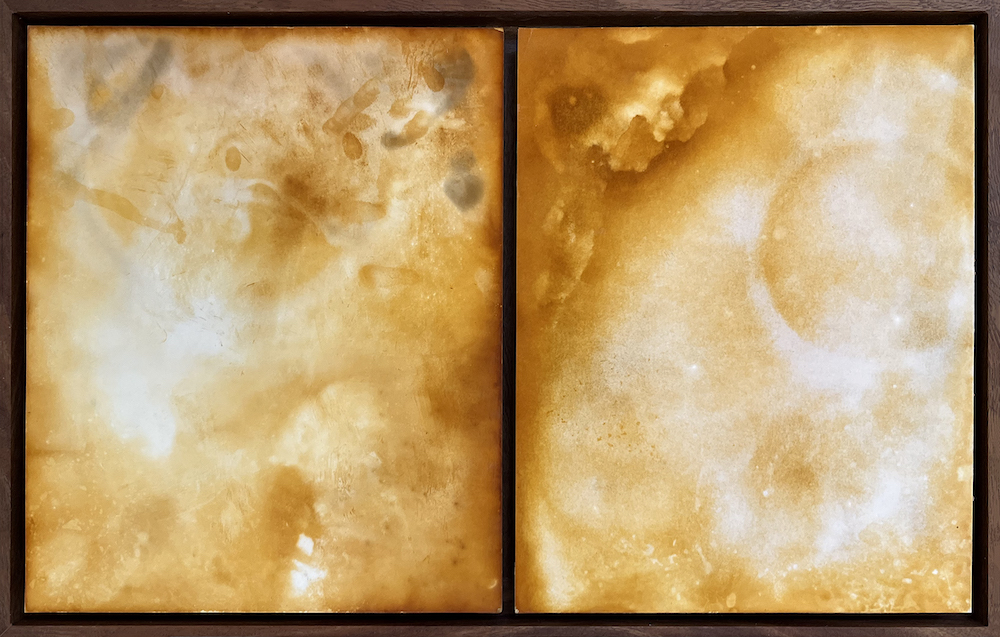

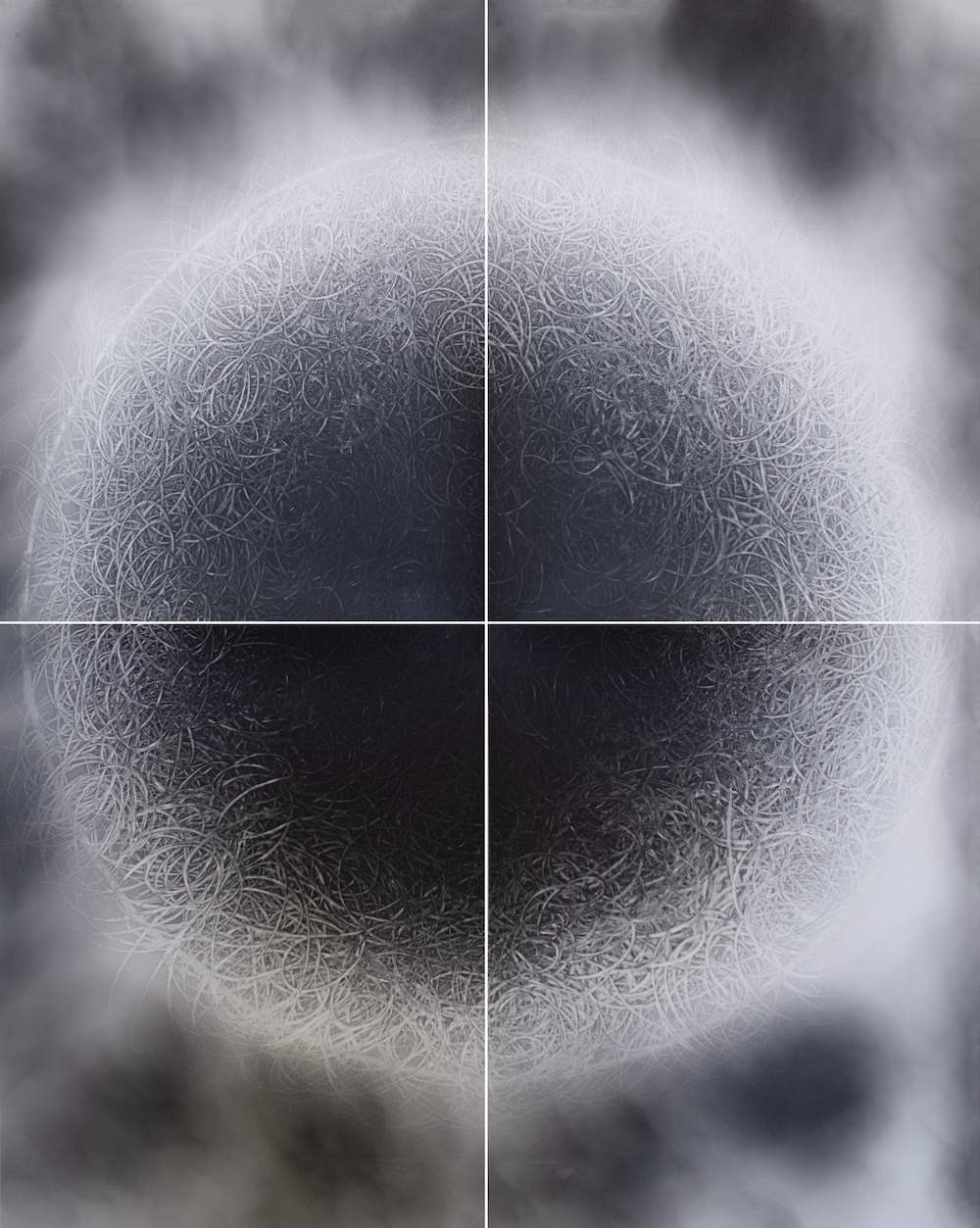

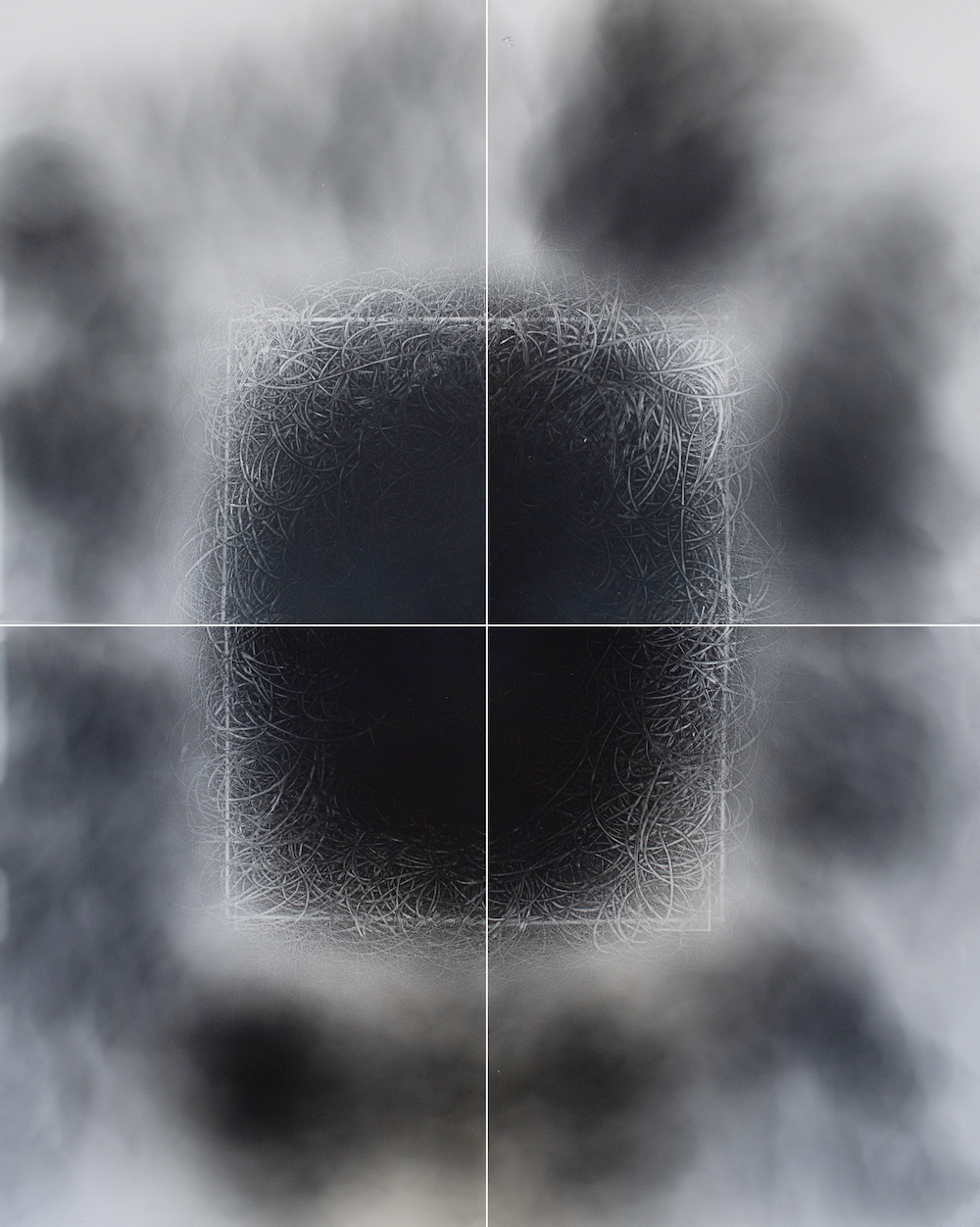

Opening today, Margot Kalach’s solo exhibition at Salon ACME showcases her latest dive into camera-less photography. Using custom-made optical tools, her ethereal and hypnotic black and white light-drawings act as dynamic canvases for art, play, and science. On display until February 11, the exhibition also features an assortment of richly textured artworks crafted from oxides and residual photographic chemicals. The works are incredibly beautiful, simultaneously evoking visions of deserts, galaxies, bays, petri dishes, and the unreachable corners of the cosmos.

Salón ACME, launched in 2014, is an authentic art platform and event for emerging artists in Mexico and globally. With 10 editions, it’s a key player in the contemporary art scene, connecting artists, curators, and collectors.

In the first part of our two-part interview, the artist and I delve into the genesis of her custom tools and delve into the profound philosophical implications they hold for photography.

—Vicente Isaías, Latin American Editor

Margot Kalach (Mexico City, 1992) holds a degree in photography from Bard College (2016). She attended the SOMA Mexico Academic Program (2017-2019). She was a recipient of the FONCA Young Creators scholarship (2019) and a resident at Casa Wabi (2021). She has a wide participation in group exhibitions, as well as three solo exhibitions: 08J3C71V17Y (Bard NY, 2016), The Dream of the Stone (Ex Convento Tepoztlán, 2021) and Reverberations (Cordoba Lab, Oaxaca, 2022). She has participated in fairs such as La Feria del Millón 2019 (Bogotá, Colombia) and PhotoLondon 2023 (London, UK).

Experimentation, play, and accident are an important foundation of the artist’s material universe. On a large scale, the projects seek to return subjectivity to the center of scientific models, mechanical systems, and the knowledge structures that are at the center of our daily lives today. Margot emphasizes intimate technologies, the organic and complex evolution of time and matter, and the philosophy and speculation of science as tools for creation.

Follow Margot Kalach on Instagram: @margotkalach

Vicente Cayuela: Margot, I am very excited to share your work at Lenscratch. You’re currently participating at Salon Acme, which opens today. What can we anticipate?

Margot Kalach: Thank you very much for the invitation, I am very happy to be “here.” At Salon ACME I will present two branches of my work, they both deal with the photographic in different ways.

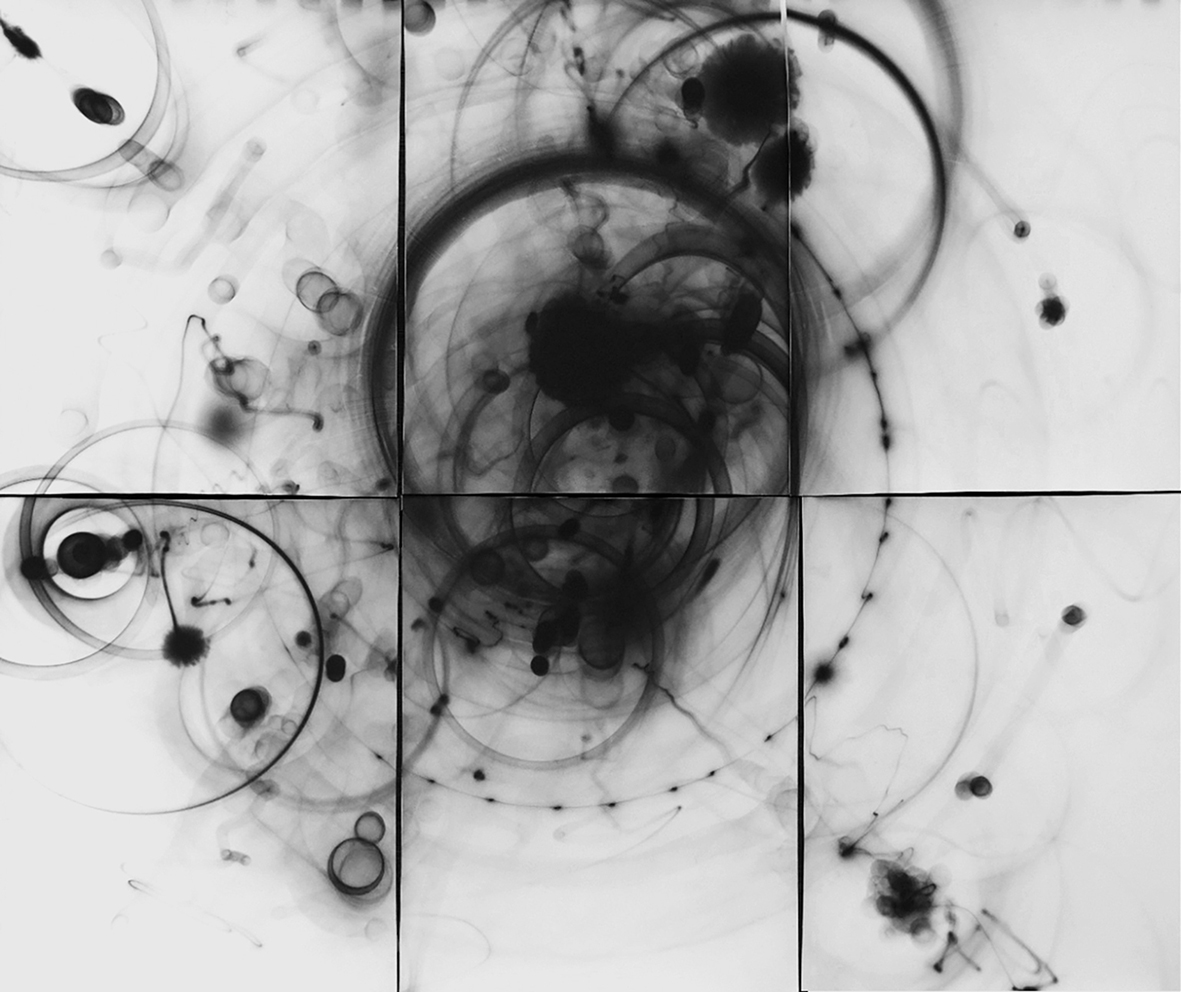

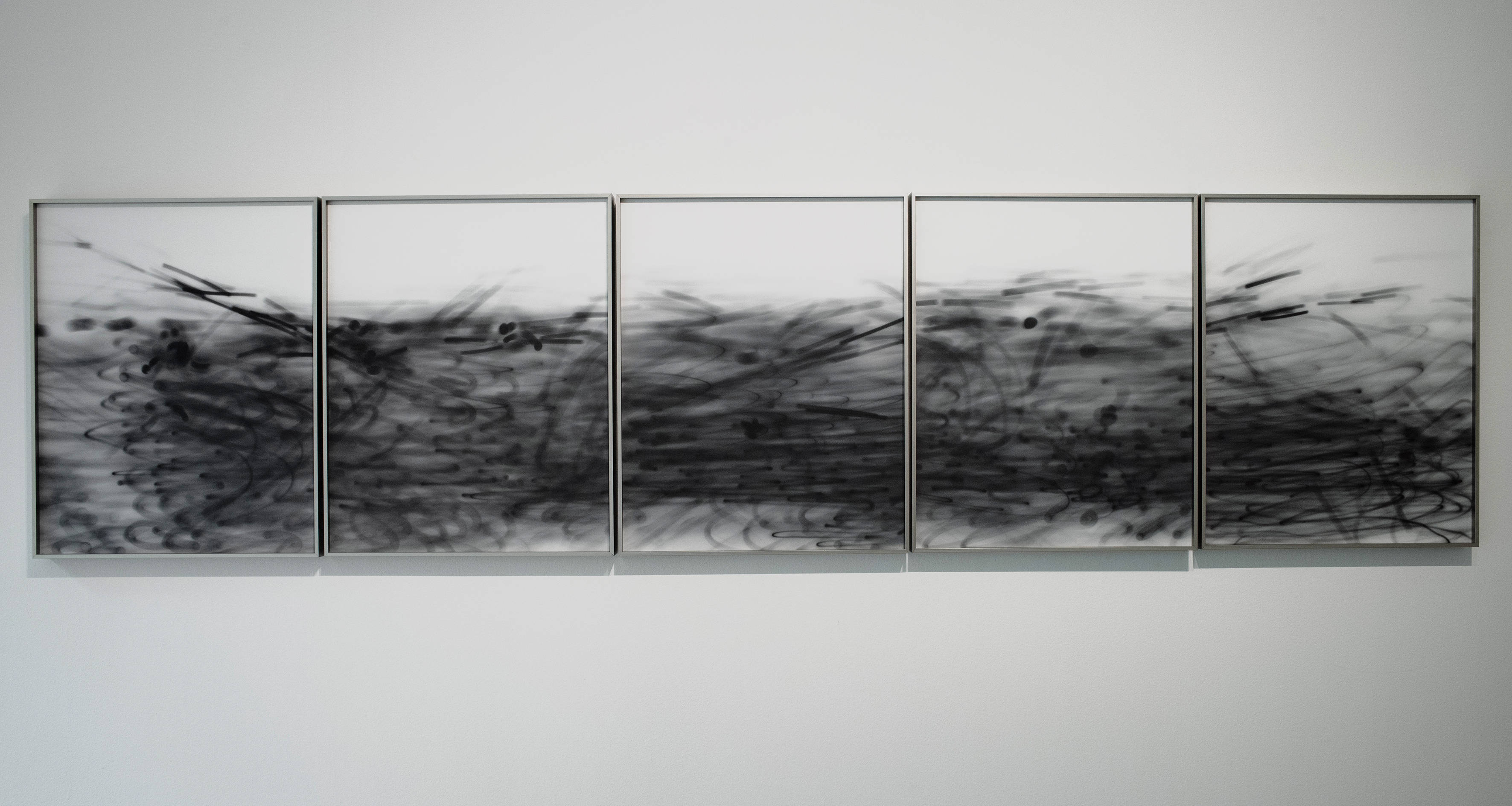

One, the silver gelatin, black and white work, under the practice of experiments in the dark room. These deal with light, movement, and something I think as “intimate technologies,” which are home-made tools that become an important active agent of the work.

I will be showing the most recent series of such experiments, which happened at the residency of ITHAQUE (Paris) this past November (2023), and are quite different from my past work. For these, I designed a “light pencil”: an old vacuum cleaner tube with a crystal ball attached to one end of it, inside the tube [there are] LED-lights that project onto the photosensitive paper, which is laid under a sheet of glass that I scratch while light-drawing.

VC: And the other?

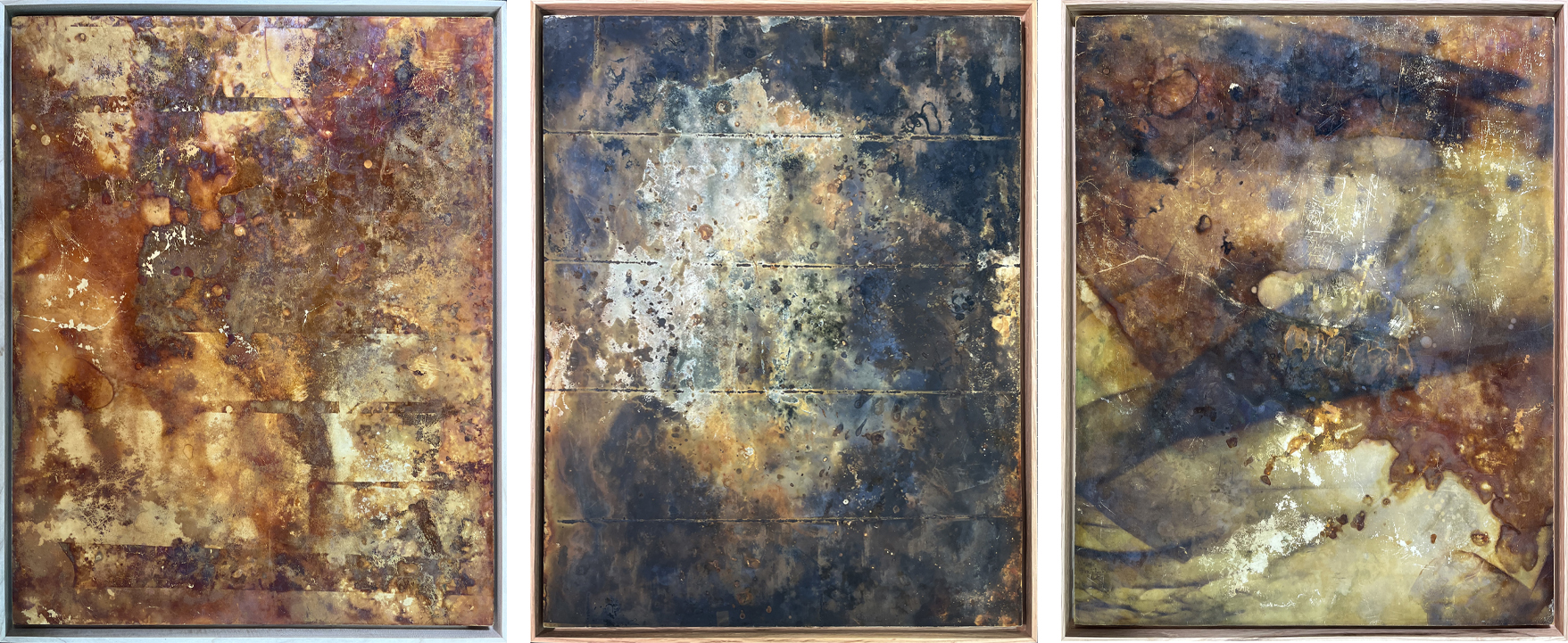

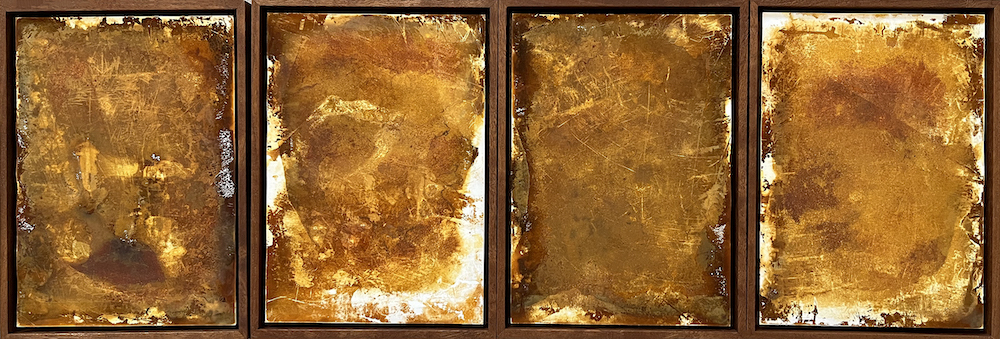

MK: The second series deals with a different practice that happened in a fortunate encounter. After a long period of not cleaning my studio, my leftover chemicals began to rust a metal tray. I am a fool for any traces of the passing of time, and oxide proved to be a great one. Since then, I have been using iron oxide as the material to intervene photographic (and other) types of paper. In some large iron tubs, I vert the residue chemicals from the darkroom to keep feeding the oxidation process.

The results are incredibly beautiful crystallizations of organic activity that have proven to be an unstoppable fountain of rich creation. Next to the darkroom is the oxidation room, made up of many of the darkroom “leftovers.” Being present in these spaces makes me feel like I am dealing with very essential materials in a very raw state: light, water, oxygen, metal… and their constant transformation as a remainder of a universe where matter is never destroyed, but constantly moving.

VC: How did you start integrating experiment, play, and accident into your artistic work?

MK: Every moment of surprise, of the unexpected that seeps into the work, is a great encounter.

To embrace the fact that we are not total agents in any event, that something always remains unknown, has led me to appreciate and inflate experiment, play, and accident, as important pillars of the work. It is also a reminder about the nature of human “progress”, which as a tide that moves forwards also moves backwards, and sideways, and all ways.

Play is at the center of investigation. Accident reveals the unexpected. Experiment allows a space where knowledge, play, and accident bring us in contact with things we could never even imagine. Imagination is both a potent accelerator and a self-imposed limit. Accident, play, and experiment break the boundaries of our own preconceptions.

VC: There is so much beauty in the highly manual and explorative character of your work, especially in this idea of “closeness” and “intimacy” with the tools of an artist. Can you expand on your intimate technologies and how they help you achieve your creations?

MK: We live in a world where we have lost connection with our tools and the objects around us. I find it important to have a more personal connection with the tools that end up having such a big impact in the creative process. I want the work to be a reminder of how we are naturally scientific, technologic, and artistic beings, no matter the task at hand.

Being intimately involved with my “machines” is also a reflection upon the idea of technology not only as what we acknowledge as cutting-edge, but as a long history of humans interacting with matter in both a personal and methodical way. A large part of my work is (re)situating our scientific/technical self in the human gut, through art.

[These] optical and mechanical tools I have built to take part in the creation of my images, [generally] must offer: the possibility of movement, the projection of light, the registering of the encounters between myself and my tools through that light, and the flexibility to a high level of improvisation.

The intimacy lies first in their imagining, then in their truly DIY nature, made with mostly found objects I have collected through the years, usually laying around the studio waiting to be used.

Another level of intimacy is their specific design to help me respond or dive into my philosophical preoccupations. It is in the process of assembling and learning to use my own tools that really internalize questions and topics that are deeply personal to me.

From the imagining to the using of the tools, the focus has become highly oriented to the paradox of emphasizing on science and technology in order to connect with the human, the irrational, and the anti-mechanical.

I seek to push repetitive action to a state of disorientation aided by an exaggerated and zero-accuracy tool. To rely on wave mechanics, frequency, amplitude, duration, patterns, orders, and systems to reach the breakdown of predictability (chaos).

Finally, to reflect on the importance of thinking through doing – it is the process that reveals something essential about the world; designing and using these intimate technologies has been an expansion of a deeply emotional and intellectual space.

VC: Were you always interested in camera-less photography and image-capturing devices?

MK: I always found the camera a fascinating invention. I started to wonder if photography could be used to make a portrait of itself, photography about photography, or photography about light. There have been other artists with a similar preoccupation, and of course this exploration can happen in using any conventional camera.

I actually began my search with a digital camera, engaging in long exposures and some minimal darkroom experiments. Yet, it was in really wanting to think the photographic moment as something monumental, as an instant of existential significance, that the camera stopped feeling useful. I wanted to able to amplify and focus on the contact of the subject with a light-based mechanical device in the search of some truth.

The first move was to bring photography to its bear minimum, to strip it of things like subject matter, composition, and reproducibility (making each act a novel one). The characteristics that finally remained were light, movement, and photosensitive material. I began small, with a pair of magnifying glasses, a light source, and some photo paper; slowly I realized how essential movement was in order to record what I was looking at, and I began to build rails and use turning wheels to aid with the motion. It was like setting up light-traps in order to begin to know light, and understand it better.

VC: Outside of your relation to these mechanisms, how do you perceive intimate technologies influencing the understanding or relationship between the viewer and your art?

MK: For the viewer to be aware of this whole universe of tools and objects surrounding the work helps to contextualize the images in a space full of a sense of curiosity and a deep peruse of meaning.

In the recognition of this universe, the visible movement and unrest present in the final images expands. It continues outside the frames of the paper to become part of a more complex process, where the images are just one part of a larger ongoing gear.

I am [also] interested the role that imagination plays in the act of knowing and constructing, [so another] important aspect is [that] the viewer needs to … [imagine] how the work was made, since it is never fully uncovered.

VC: Is there any specific experience or event that has influenced your creative approach?

MK: During my last year in university, I decided to work only at night. Night-time is a different time, it immediately puts things in a different light´. My dorm room was right next to the science building. I would sneak into it the middle of the night and try my luck with unlocked doors into the labs.

It became a very magical and personal space to work in, constructing scenes and sculptures for the camera out of any objects I would find. I would imagine the possible uses of these unknown instruments, and create a personal and fictional world from these public and institutionalized spaces.

The images that came from these explorations form a series called 08J3C71V17Y (objectivity), and I see it as the beginning of the work I do now. In one way or another this has kept me “playing in the lab” since 2016.

VC: Are there specific philosophical concepts or thinkers that have particularly inspired you?

MK: Peter Galion’s books Objectivity and Einstein´s Clocks. Clarice Lispector´s Agua Viva. Claude Bernard´s Aesthetics of the Laboratory. James Joyce´s Finnegans Wake. Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Virginia Wolf, A Room of One’s Own. Lewis Mumphord, Techniques and Civilization. Susan Sontag´s On Photography. Henri Bergson‘s Creative Evolution. Janna Levin´s Black Hole Blues. Edwin Abbott´s Flatland. Carlo Rovelli´s The Order of Time. Ziya Tong´s The Reality Bubble. Paul Davie´s The Demon in the Machine. Edward Tufte´s Visual Display of Information. Chiara Marletto´s The Science of Can and Can´t.

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025