Mexican Week: Alexandra Germán

Mexican-English cloud-connoisseur Alexandra Germán has captivated audiences with her exploration of meteorological phenomena for over a decade. Her latest series Diáfano, however, evinces a remarkably sophisticated approach.

Delicately burning scientific data onto vivid photographic prints of the sky, the artist’s newest intervened landscapes elegantly infuse her work with layers of intricate information.

“Diáfano originates from the archive of light-hour measurements stored in the National Meteorological Service of Mexico City,” explains the artist. There, atmosphere data is collected and then “visualized on a small strip of paper … with a carbonized line – continuous, intermittent, or varying, depending on atmospheric transparency.”

Tastefully merging the aesthetic with the scientific, the charred lines on the surface of each print reveal gold, silver, and copper plates placed under her celestial photographs.

In this interview, Alexandra Germán urges viewers to reflect on the intricate bond between human perception and the unifying mantle enveloping us, reminding us that everyday phenomena is indeed something extraordinary.

—Vicente Isaías

Latin American Editor

Alexandra Germán (Mexico/England, 1986) is a photographer and visual artist, living and working in Mexico City. She holds a Master’s degree in Arts from the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos (2012). Since 1993, she has attended various workshops in institutions such as the Cultural Center of Spain, Morelense Center for the Arts, National Institute of Fine Arts, Autonomous University of the State of Morelos, and Complutense University of Madrid. Some of her exhibitions include “Notes on Meteorology” at the National Meteorological Service (Mexico City, 2020), “Three Variations on the Same Theme” at Salón ACME No. 6 with Patricia Conde Gallery (Mexico City, 2018), “Reflections on the Sky” at the Art Museum of Ciudad Juárez (Ciudad Juárez, 2017) and at No-Automático (Monterrey, 2017) as part of a short-stay program supported by the PAC (Patronage of Contemporary Art). Germán has received various supports for her artistic production such as the FONCA Artistic Residency Program scholarship to attend a residency at Banff Centre (2019), the FONCA Young Creators Program (2012-2013), the Stimulus Program for Artistic Development PECDA of the state of Morelos (2009-2010), the second photo essay training program Foto Ensayo (Pachuca, Hidalgo, 2009-2010), as well as the scholarship for master’s studies and studies abroad CONACyT (2010-2012). Germán’s work has been selected to participate in several festivals and competitions in Mexico such as the “Third Contemporary Photography Contest of Mexico” (Nuevo León, Monterrey, 2017), the “II Oaxaca Photography Biennial” (Oaxaca, 2016), “XXXVI National Young Art Encounter” (Aguascalientes, 2016), “1st Morelos Photography Catalog” (Cuernavaca, 2015), “Fifth International University Visual Art Biennial” (Toluca, 2012), “First Digital Technologies Festival MOD” (Guadalajara, 2008), “FotoFest Morelos” (Cuernavaca, 2011), and “Local Code” (Cuernavaca, 2007). Germán has collaborated on various projects and artistic collectives such as with the Real Estate Art Collective (Mexico), Art by Mail (Mexico), Exchange Stories for Cigarettes (Spain), and the animation collective Animatitlán (Mexico). Her work has been published in Vougue magazine, Capitel, Mexicanismo, and MirArte. Germán is represented in Mexico City by Patricia Conde Gallery, with whom she has participated in various art fairs such as Zona Maco and Zona Maco Foto, Lima Photo, Miami Context, Paris Photo LA, Paris Photo, VIP Art.

Vicente Cayuela: The transformation of landscapes at different time intervals has been a recurrent theme in your work, as evident in projects like 30 Minutos de Mount Norquay (30 Minutes of Mount Norquay, 2019) and Diez Minutos de Vida (Ten Minutes of Life, 2018). Where does this fascination with the passing of time and meteorological phenomena originate?

Alexandra Germán: I believe it arose from the desire we’ve all experienced at some point not to want things to change, for everything to remain in perfect harmony. However, the reality is that everything changes—our surroundings, ourselves. Even if days seem unremarkable, the sky is never the same, Earth is in constant rotation and translation, and both animate and inanimate objects, through their presence or absence, alter the way light propagates. Our existence as humanity causes ecosystems to shift inevitably. In my reflections on landscapes, I discovered that nothing depicts change as unmistakably as a cloud. They serve as a perfect example of what cannot be contained or prevented from transforming or disappearing. Clouds exhibit ephemeral characteristics, subject to external factors beyond their control, almost like an analogy for our own existence.

VC: How did you begin working on the Diez Minutos de Vida series, and can you delve into the specifics of the duration time of a cloud?

AG: Diez Minutos de Vida originated from my readings on popular science about meteorology. In one publication, it was claimed that, on average, a cloud lasts for ten minutes before either disappearing or transforming into a completely different form. This assertion sparked my doubt, prompting me to verify its accuracy. I climbed to the rooftop of a friend’s building on one of those hazy days in Mexico City, where pollution tints the sky with earthy tones. There was minimal humidity, and only a tiny cloud lingered low on the horizon. I decided to photograph it at one-minute intervals (each film cartridge contained ten sheets of instant film), and, to my surprise, it remained in the same spot for ten minutes with minimal change in shape.

This experiment fascinated me, leading me to replicate it in various locations, always noting the shooting location, time, date, and atmospheric conditions. I realized that a cloud’s duration depends on numerous factors, not just the passage of time. I conducted this experiment in different parts of the city and later in other states, revealing that topography is also a crucial factor in these formations’ evolution. The piece 30 Minutes of Mount Norquay, as you mentioned at the beginning of the interview, is part of this exploration. This mountain is located in the Rocky Mountains that span Alberta, Canada. Documenting its surroundings helped me discover new types of clouds that rely on these mountains to exist.

VC: What challenges or interesting discoveries have you encountered during the creation of these cloud-centric projects? And how has your role evolved from being primarily a photographer to becoming more of an observer in the context of studying clouds and meteorological phenomena?

AG: I believe my photographic practice has become enriched by gaining more awareness of my surroundings and the nature we interact with daily. Beyond capturing images solely for aesthetic appreciation, I can now better understand, according to my interests, why something appears beautiful to me. As I develop more projects, I continue discovering new concepts I’d like to explore. Engaging with scientists has deepened my fascination with numerous aspects of our atmosphere that were previously unknown to me. The opportunity to measure these phenomena seems incredible, and among the various types of measurements, in addition to the heliograph and hygrograph, one that I find particularly beautiful due to its collective nature is radiosonde observations. This type of measurement occurs simultaneously worldwide, providing a global perspective on the conditions of our atmosphere.

VC: In addition to these time experiments with film photography, one of your earlier project, Studies of Precipitations (2016), contributes to showcasing the displacement of clouds through GIFs.

AG: A while ago, while researching types of observations for weather prediction, I came across records of supercells in motion captured by various satellites. These images aimed to monitor the development of a storm and determine whether it was necessary to alert the population about its danger. From there, the idea emerged to create my own records from an airplane window of formations that might or might not become threatening. The intention was simply to observe their movement while I, like the clouds, traveled from one point to another.

VC: You also have built sets to construct some of your photographs, as you did in your project Metamorposis de una nube (Metamorphosis of a Cloud, 2013–2014).

AG: In my earlier work, I used to create dioramas, composing entire landscapes to later photograph and generate specific atmospheres through post-production. Each image could take me months to complete. To depict the sky, I had to observe it for extended periods, studying how light pierced through the clouds and how they altered their shapes and colors. After a while, I realized I needed to know more about this part of the landscape we interact with daily, even if unconsciously. So, I began by learning the names and peculiarities of each cloud, enabling me to replicate them in Metamorposis de una nube. This project serves not only as an illustrated catalog for myself but also references the ephemeral, ever-changing, and uncontrollable nature of clouds.

In this series, a single cloud becomes my main character. In all seven photographs that make up the series, it’s the same cloud confined to a single space, hence the threads in the image to prevent it from “escaping,” even though it’s in a room without a roof. I believe this series not only speaks for itself about transformation but also represents a transitional stage in my production. I shifted from focusing on constructing dioramas within my studio to looking outside for more answers to what began to interest me. In this series, I reflect on the transient, ephemeral, ever-changing, and elusive nature—a representation of the beauty in simplicity and the pursuit of understanding our atmosphere in an interdisciplinary manner. This meta-narrative is what I believe persists in the rest of my work.

VC: Before we talk about your newest work, could you tell us about the artworks and writings you used in your project Variantes (Variants, 2017–2018), and how they add to the way you think about the sky in your art?

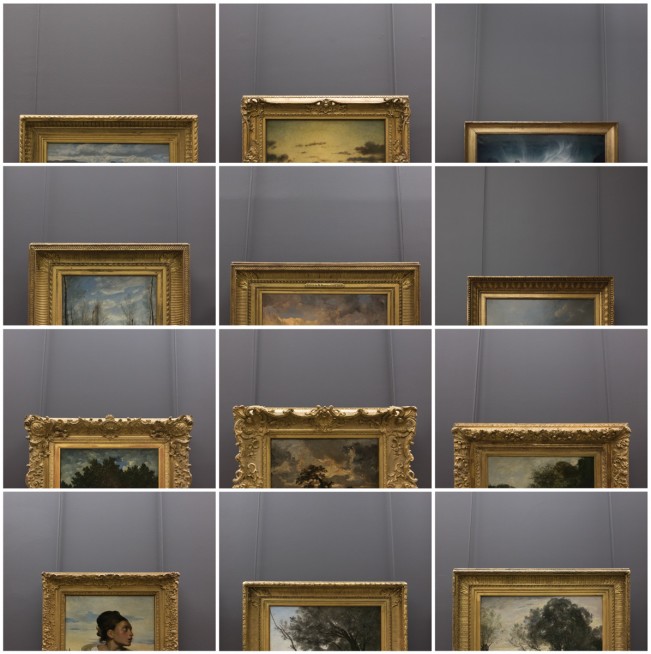

AG: Variantes arises from my observation of how the sky has been represented in literature and painting, starting with the Romantic painters. In this series, the idea was to fragment paintings into two parts, from the horizon upwards, extracting that essential part that shapes the landscape’s peculiarities within each artist’s work. The intention was to transform them into free skies that, rather than referencing the author or artistic movement, remind us of the sky seen through a window.

In literature, I followed a similar approach, gathering excerpts from stories and novels that included descriptions of the environment where the narrative unfolds and the atmospheric conditions perceived by the character. These conditions influenced the character’s emotional state and established the story’s atmosphere.

My approach to studying clouds has been diverse, starting intuitively from the realm of art, particularly through disciplines I hold a deep love for, such as painting and literature. In both fields, I explore interpretations of various authors towards meteorological phenomena, whether accurate depictions or purely imaginative, as often seen in science fiction. The collection of pictorial and literary cloud records in Variantes aids me in envisioning new skies and seeking their existence in the truth that science can provide.

VC: When it comes to your new project Diáfano (Diaphanous, 2023), how has your approach to this creative process evolved over time in comparison to your older works?

AG: As I have continued my research on meteorology and cloud physics, I have felt the need to engage with more people for a better understanding of this science. Diáfano is my first project arising from this interaction. Although it’s not a collaborative effort, its conception came from interacting with scientists and an institution dedicated to my areas of interest, unlike previous projects that emerged from a solitary process.

VC: Can you elaborate on the manual interventions you performed on your sky images in Diáfano?

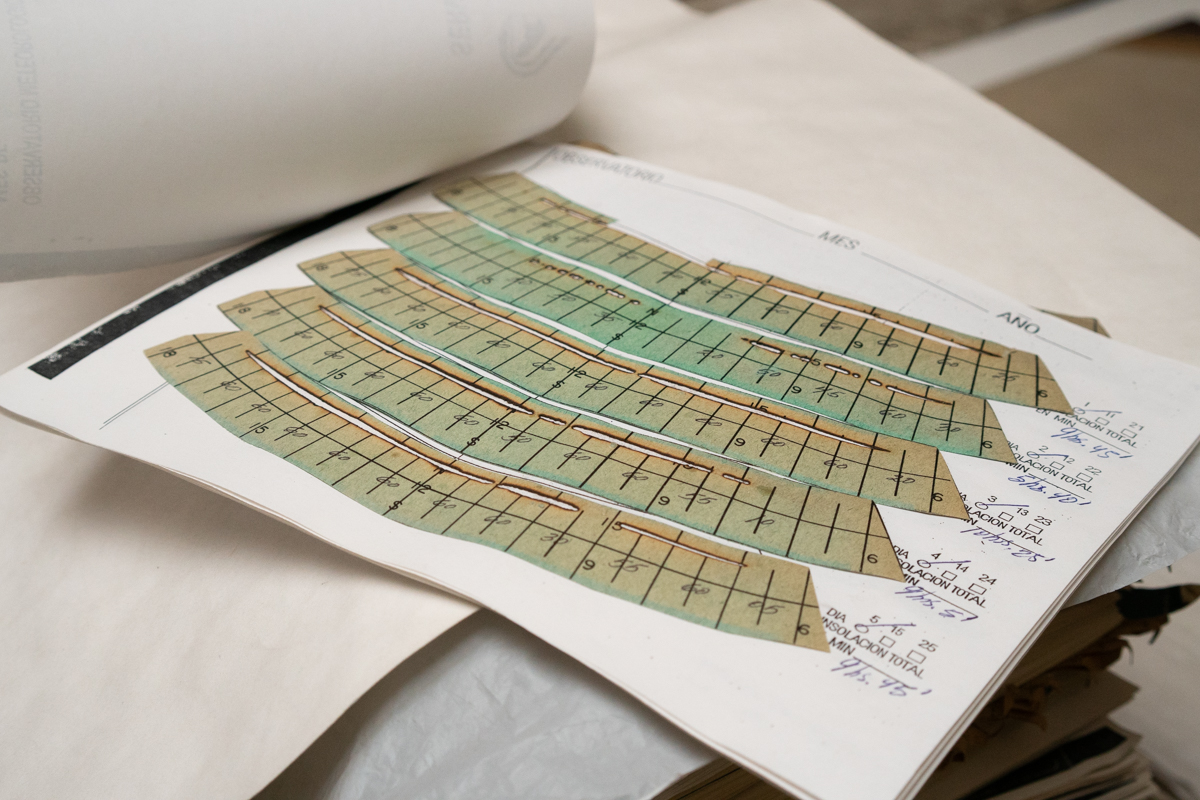

AG: Diáfano originates from the archive of light-hour measurements stored in the National Meteorological Service of Mexico City. Each day, comprehensive information about various aspects of the atmosphere is collected, including the daily sunlight hours and intensity. This data is visualized on a small strip of paper, approximately twenty centimeters long, which ends the day with a carbonized line – continuous, intermittent, or varying, depending on atmospheric transparency.

Meanwhile, I regularly captured sky photographs from my studio window as a reference for other projects and as an observation of what began to captivate me. I decided to connect this body of work with the archived light-hour data. Initially, I selected images I deemed relevant and then searched for the corresponding carbonized strips from the same dates as my sky photos. After photographing these strips, I digitally overlaid them onto my images to guide the physical intervention.

The next steps involve printing on acid-free, 100% cotton paper and patiently burning it with a soldering iron. Once this part is complete, I place the metal sheet (whether gold, copper, or silver) on an adhesive surface, serving as the base for mounting the intervened photograph.

VC: In the landscape of contemporary photography, how do you approach your relationship to “the photograph” both as object and surface?

I have always felt the need to engage with my work in a tactile way, whether by constructing objects to photograph later or by intervening in the image itself during its assembly. While I have always been very cautious not to “damage” the print, in Diáfano I thought there was no other way to do it than by “damaging” a perfect print, though it remains a very controlled process. I believe the need to manipulate materials is a way of approaching my work, allowing me the possibility to continue reflecting on what I am doing. I think that working with its materiality gives it a more personal character. Working on Diáfano requires a lot of time since it is a manual process that I cannot rush. This repetition and knowing it will take a while allows me to completely abstract myself from my surroundings and immerse myself in my own thoughts. Perhaps only sound comes to define the rhythm with which I progress, so I prefer listening to classical music or silence to respect this time.

VC: Your study of tools like the heliograph had a big impact on how you create this series. How does this connect metaphorically? And how do you blend the scientific side of these tools with the artistic side of your work?

AG: I find it fascinating when the intangible is revealed or when a concept that seems abstract materializes, as in the case of characteristics of our atmosphere and the Sun. The series title refers to the transparency and clarity of things, evoking Romanticism’s principles associating the sky with an abstract representation of our emotional state. Diáfano also alludes to the transparency of our atmosphere affected daily by various factors like pollutants, observable through constant measurements.

The Sun, demonstrating its energy through radiation and concentrated by the heliograph, is depicted using carbonized strips to reveal the presence of what exists in that distant space. Despite being millions of kilometers away, it manifests in our daily lives, vital for our existence. Despite the often unnoticed distance, it traverses our atmosphere, revealing its strength by carbonizing a strip of paper. To me, the sun’s opening in our sky allows what resides in that other space to be shown, enabling us to look beyond our own sky to the place where the Sun dwells.

My dad is a scientist, and I’ve always found the topics he researches to be quite abstract. I imagine his perception of what I do might be similar. Despite that, I believe we both find something fascinating in each other’s subjects, even if we don’t fully comprehend them. For me, incorporating scientific aspects into my processes is a way of reinterpreting something I don’t want to be disconnected from, allowing me to understand it in my own way. It’s a kind of translation into a language I can grasp.

VC: Were there particular challenges or surprises that arose during the creation of Diáfano?

AG: It seems that challenges can arise at any point, from conception to the realization of the artwork, especially when depending on others in the process. The situation became more complicated during the pandemic as visits to the Meteorological Service were suspended, and their personnel became limited, causing delays. Beyond these challenges, now the truly challenging aspect is considering the space and how I would like the project to be exhibited.

VC: How do you envision the viewer experiencing or interpreting the poetic elements in your work focused on the sky and clouds?

AG: That’s something I’ve always been interested in hearing. I seldom talk about my poetic approaches because I’m more interested in hearing what others may perceive. I truly focus on creating something I imagine I would like to see, and it seems to me that if it evokes any emotion or reflection in someone else, they are also enjoying it.

VC: What’s in store for you in 2024? Are there future projects or themes you plan to explore that build upon the fusion of science and art?

AG: In meteorology, I’ve discovered many aspects I still want to explore. It’s a topic that impassions me and has helped me become more aware of my surroundings through understanding this science. So, I will definitely continue working on other ideas that build upon the fusion of scientific concepts and artistic expression. I’m always preparing something on my head, its hard sometimes, because I think I need to have everything solved before even spoke about it, but for now there are a couple of group exhibition in March, we will see after.

Vicente Cayuela is a multimedia artist working at the intersection of staged photography, sculpture, and installation. His handcrafted photo-based artworks create colorful scenes of graphic overload and tongue-in-cheek cultural commentary inspired by juvenile aesthetics and material culture. His work has been exhibited in New England at the St. Botolph Club, the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, and PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally. In 2022, he was awarded the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation, in Boston, MA, and was one of the seven winners of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize. Cayuela holds a BA in Studio Arts from Brandeis University, where he received the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography and the Deborah Josepha Cohen ‘62 Memorial Award in Fine Arts.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026