Juan Cruz Olivieri: Gauchos

In this interview, Zárate-born artist Juan Cruz Olivieri shares his artistic exploration of the traditions and soul of gaucho life, a central element in the folklore of his childhood. Influenced by his father’s early passion for photography, the Argentine artist has carved a distinctive path documenting gaucho communities in localities near his hometown through exquisitely lit and dynamic portraits. His series, Gauchos, presents a project filled with great sincerity and emotion in photographing his subjects that goes beyond the documentary genre: “Photography for me is not only a form of artistic expression but also a way to preserve and perpetuate our cultural heritage,” the artist remarks. Today, Olivieri’s photogaphs invite us to witness the traditions, folklore, and perseverance deeply rooted in the Argentine countryside.

Juan Cruz Olivieri

He was born in Zárate, where he currently resides, in the province of Buenos Aires in the year 1980. A professional Electrical Engineer by trade, he first encountered photography in 2012 when he attended workshops by photographers Gustavo Di Mario, Ignacio Iasparra, and Alberto Goldstein.

Follow Juan on Instagram: @2015_juan_cruz_

Gauchos

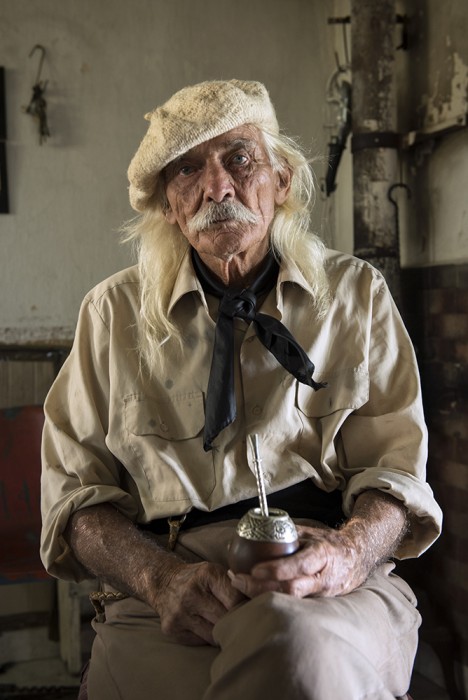

Gauchos in Argentina embody an emblematic and representative figure of the men who conquered the pampas. In my work, I strive to capture an intimate photography style, transcending from being an intrusive object to becoming a confidant in a story told amidst lights and shadows. I distance myself from the typical idealized images that viewers expect to see, allowing them to appreciate the mystical and robust identity of gaucho culture through a sense of closeness and spontaneous naturalness that I aim to express in each photo, free from ornamental pretensions. The compelling force of attraction lies in the determined way the gauchos position themselves in front of the camera, resolved to show more than just their faces: the vibrant soul of the life they embrace. — Juan Cruz Olivieri

Vicente Isaías: Juan, thank you very much for this interview. I am very happy to have come across your work. The gaucho is an emblematic figure in the history of Argentina. What motivated you to focus your photographic practice on gaucho culture?

Juan Cruz Olivieri: My first approach to gaucho culture came through folk music. In my childhood home, it was my father who listened to folk music. At that time, I didn’t appreciate that musical genre, but I am sure that it unconsciously resonated like an echo and gradually crept into my heart.

Over time, during my adolescence, I used to ride my bike to pick up a friend for school in the morning, and on the way from his house to school, most of the time, he sang songs by José Larralde. That’s when my interest in this artist awakened, and I also started listening to Larralde and, over time, more folk artists. I also began to read gaucho literature, deepening my connection with this fascinating culture. My contact with this world didn’t go beyond enjoying some folk music gatherings or festivals in the city where I live.

Then came my curiosity about photography. Although I didn’t share the passion for photography with my father, I am convinced that his influence was decisive in getting me closer to a camera. All the photos at home from our childhood were taken by him.

As an adult, I bought my first digital camera. At first, they were vacation and family photos, and then, wanting to combine the two things I love, photography with folklore, I began to approach the daily life of the “paisano,” portraying their customs and traditions. For me, photography is not only a form of artistic expression but also a way to preserve and perpetuate our cultural heritage.

VI: Considering the conceptualization of the gaucho within Argentine cultural production, I feel that it’s important for you to represent gaucho culture beyond just a literary character or a symbol of national identity. What motivates you to use photography to capture the essence and authenticity of these individuals, “without seeking formal perfection or the ornamental pretensions of their existence today” as you’ve mentioned in the past?

JCO: I use photography as a means to capture essence and authenticity because I firmly believe in the beauty of the real and the genuine. For me, photography isn’t about creating perfect or idealized images but about documenting life as it is, with all its imperfections and peculiarities.

It’s important for me that the gaucho, upon seeing my photos, feels represented. I want to capture not only the visual reality but also the emotions and experiences that define gaucho life. I aim to convey the true essence of their lifestyle so that, when viewing my images, the gaucho recognizes themselves in them and feels that their story is being authentically told.

Seeking formal perfection or ornamental pretensions in an image can distort reality and take it away from its true essence.

I believe that true beauty lies in the authenticity and honesty of an image, in its ability to convey truth and evoke sincere emotions in those who view it. By showing reality as it is, without filters or adornments, I also aim to create a deeper connection between the artwork and the viewer, allowing the image to speak for itself and tell its own story.

VI: You mentioned that it took you some time to embrace the term “photographer”. How did you get into photography? Could you tell us more about the challenges you faced and what eventually led you to identify yourself as a photographer after a long time?

JCO: My journey in photography started self-taught. Without the guidance of a formal educational program, my mentors were online tutorials, books, and hands-on experimentation. Initially, I found it challenging to adopt the title of photographer. How could I call myself that when I lacked the diplomas or certifications to back up my experience? This lack of academic validation made me doubt my position within the photography community.

However, as my passion for photography grew and my technical and creative skills developed, I began to receive recognition for my work. My photos were selected for exhibitions, I won some contests, and I received praise from colleagues and critics. These achievements, though small, gave me a sense of validation and confirmed that my self-taught approach was valid.

The turning point came when I realized that photography is not just about having a title or certification, but about passion, dedication, and the ability to capture significant moments and convey emotions through images. I began to recognize that, although my education was self-taught, my accomplishments and commitment to photography were as valid as those of any other formally trained photographer.

Ultimately, after a long period of self-reflection and growth, I realized that being a photographer is not just about how others perceive me, but about how I perceive myself. By accepting and embracing my own identity as a photographer, regardless of the educational paths I had taken, I was able to find greater confidence in my work and my ability to tell stories through my images.

VI: You were born in the city of Zárate. How did this place influence your journey as an artist?

JCO: Growing up in a smaller city like Zárate also meant facing unique challenges along the path as an artist. The scarcity of resources and opportunities compared to larger urban areas compelled me to be even more creative and to seek innovative alternatives to nurture my passion for photography.

In a city where options for emerging artists are limited, I knew I had to make the most of every opportunity. The lack of established art galleries, cultural events, or a consolidated artistic community might discourage many, but for me, it represented a challenge that I embraced enthusiastically. Instead of waiting for opportunities to come to me, I set out to create them myself.

I’m constantly sending my CV along with photos to galleries, cultural spaces, and events, actively seeking opportunities to showcase my work. While it can be challenging to receive responses or find platforms willing to exhibit the work of emerging artists, I persist in my search, trusting that each submission could mean a future opportunity.

This proactive attitude has not only allowed me to increase the visibility of my work but has also been a source of motivation and constant learning. Through each submission, I’m building connections, receiving feedback, and honing my craft, preparing myself for the opportunities that lie ahead.

In summary, my experience in a small city has taught me the importance of perseverance and creativity in seeking opportunities to showcase my work. Though the path may be challenging, I’m determined to forge ahead, trusting that each step brings me closer to my goals as an artist.

VC: How has it been for you to immerse yourself in these communities, and what was your first approach to rural life in Argentina? How do you approach portraying your subjects?

JCO: Initially, my goal was to return home with as many images as possible; a large number of photos equated to a successful outing in my mind. However, over time, my perspective and approach have evolved significantly. Now, my greatest enjoyment lies in discovering stories and engaging in deep conversations with the people I encounter along the way.

There have been occasions when I’ve spent an entire morning in a captivating conversation with someone I’ve met, without even taking out my camera. I recognize the importance of knowing when not to take a photo, whether it’s because the situation might unfavorably affect the subject or because the conversation is so intimate that it would be disrespectful to interrupt that moment. These experiences have taught me that the true richness of photography goes beyond simply capturing images; it’s about connecting with people, understanding their experiences, and learning from their stories.

By achieving these conversations and getting to know people more deeply, I’ve discovered that this not only enriches my personal experience but also enhances the quality of my photographs. When people feel comfortable and relaxed around me, I can capture more authentic and genuine moments. Smiles are more sincere, gazes are deeper, and emotions are more palpable.

This evolution has not only influenced my work as a photographer but also my personal growth. Through these deep interactions, I’ve gained a greater understanding and appreciation for the diversity of experiences and perspectives that exist in rural areas. It has taught me to be more empathetic, receptive, and open to new ways of seeing the world.

The process of transitioning from simply capturing images to seeking and sharing stories has been a fundamental part of my evolution both as a person and as a photographer. It has allowed me to not only grow in my art but also in my understanding of the world and myself.

VC: Is there any gaucho tradition that particularly catches your attention, one that you find problematic, or a moment you have experienced while capturing images that has deeply marked you?

JCO: The experience that moves and sensitizes me the most isn’t a gaucho tradition per se, but it’s closely linked to our culture: the “toreo de la vincha” in Casabindo, Jujuy, during the celebration of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. This celebration, dating back to colonial times, holds deep religious and pagan significance that has been passed down from generation to generation over the centuries.

The “toreo de la vincha” is much more than a simple bullfighting practice; it’s an expression of faith and gratitude towards the patron saint, as well as a plea for the protection and well-being of the community. Witnessing this ancestral ceremony, where religious and cultural elements merge, is a deeply moving experience that connects me with the deepest roots of our identity as a people.

For the inhabitants of Casabindo and the region, the “toreo de la vincha” is not just a tradition but an integral part of their cultural identity. It’s a way to honor their ancestors, keep ancestral traditions alive, and reaffirm their sense of belonging to the community.

Another cultural aspect that has deeply impacted me is the devotion to Gauchito Antonio Gil in Corrientes. This legendary figure, who emerged as a popular hero and protector of the humble, has transcended the barriers of time and space to become a symbol of hope and solidarity for many people throughout Argentina.

Witnessing the fervent devotion and manifestations of faith towards Gauchito Antonio Gil is a unique experience that reveals the deep spiritual and cultural connection in our society. Capturing images of this popular devotion has allowed me not only to document a tradition rooted in the history of our country but also to reflect on the transformative power of faith and solidarity in our lives.

In both cases, these movements of faith are deeply moving to me, even though I may not fully understand them. However, I am deeply moved and sensitized to see how people hold on to these beliefs, how these traditions are an integral part of their lives, and how they find comfort and hope in them.

VC: Could you tell me the story behind this image?

JCO: The scene is reminiscent of times past when the gaucho pilgrimage in Luján was an eagerly anticipated annual event, where people from far and wide would come to participate in the tradition. Although the pilgrimage is no longer carried out as it was some years ago, due to concerns about animal welfare and many reports of the poor condition of the horses, the physical exertion they were subjected to in making the journey from their homes to Luján, this image captures the essence of that historic moment and the unique relationship between the gauchos and their horses.

At that site, the countrymen who arrived the day before would gather to spend the night and then join the pilgrimage. Throughout the area, makeshift tents would be set up, mostly with tarps tied to carts or sulky, while the smoke from the fires announced the preparation of water for mate, interspersed with some sips of wine by a grillmaster who was eager to prepare lunch from very early on. All of this created an atmosphere of camaraderie and anticipation for the event, which was different from the typical rodeos or folk festivals; in that space, cumbia music predominated, resonating from large sound systems.

Next to the site, the Luján River meandered. Although it was not a river with a large flow, it was wide enough for the horses to drink and refresh themselves before the parade. This aquatic environment also provided the opportunity for the gauchos to demonstrate their courage and skill in various recreational activities, under the watchful eyes of the other participants.

VC: In your opinion, how does the gaucho exist in the country’s collective imagination as an icon of cultural resistance? In your experience as a photographer, have you encountered social or political issues that particularly affect these communities?

JCO: Despite the social and economic changes that have transformed the Argentine landscape, the figure of the gaucho remains a symbol of national identity and a reminder of the country’s cultural richness and diversity. Furthermore, the image of the gaucho has been idealized in literature, cinema, and visual arts, contributing to its mythification as a cultural hero. Through these representations, the gaucho becomes a symbol of cultural resistance that transcends geographical and temporal boundaries, inspiring future generations to defend and preserve their cultural heritage.

In the circles where I move to photograph, I mainly encounter people who are employees, farmhands, and other members of rural communities. In my work, I focus on giving voice and visibility to these communities, as they are often the ones who face social and political issues most directly. It’s important to note that my interest is not in showcasing landowners or estate owners, but in portraying the life and experiences of those who work the land and play a vital role in the rural economy and culture. They deserve to be recognized and valued for their contribution to society. By focusing on employees and farmhands, I seek to capture their stories, struggles, and aspirations, and to show the humanity and dignity in their everyday lives.

Furthermore, it’s important to note that the photography I do never attempts to be a denunciation or a display of struggle, but simply a way of life that I value and try to dignify. My goal is to capture the beauty and authenticity of these rural communities, highlighting their humanity and their connections to the land and each other. Instead of focusing on the negative aspects, I seek to highlight the resilience and strength of these individuals and their communities. The gaucho is a humble and respectful individual, with a big heart that offers everything they have at their disposal. Their nature is hospitable and welcoming, able to consider you as a brother when they perceive that you are taking their history, culture, and way of life seriously. It’s at that moment that they open the doors of their home and heart to you, willing to share their traditions, experiences, and wisdom with you, in a gesture of generosity that reflects the deep roots they feel for their land and their heritage.

VC: Let’s talk about your inspirations. Is there any photographic reference whose work you admire and also focuses on capturing the essence of gaucho culture?

JCO: There is a work by the photographer René Burri that I appreciate; the book is very interesting as it combines images with texts by Jorge Luis Borges. What I particularly highlight about the work is its ability to capture the essence of gaucho culture, despite Burri not being an Argentine photographer and perhaps not knowing all the nuances of this culture perfectly. His ability to immerse himself in an unfamiliar environment and convey the authenticity and beauty of rural Argentine life is truly impressive. His images go beyond the surface to explore the connection between the gaucho and his environment, as well as the traditions and values that define his way of life.

VC: Considering the vast cultural production around the gaucho icon, is there any book, song, or other work that you would like to share or that has significantly marked you?

JCO: It’s difficult to choose a single work or cultural expression that stands out above the rest. In each stage of my life, I have discovered and valued different aspects of culture, finding pleasure in a variety of books, musicians, and experiences. Each journey, each encounter, and each new story I discover enrich my appreciation for cultural diversity and inspire me to continue exploring and learning with every step I take.

VC: Let’s wrap up by talking about the future. Do you have any projects in mind for this year?

JCO: I would like to be able to complete the project “Habitantes Silenciosos.” It’s a project that I have been working on in parallel with the one about the gauchos. I have already finished the editing, but I need that last push to be able to print it. After that, of course, I will continue to expand the work on the gauchos and keep looking for opportunities to showcase Argentine culture. My goal is to continue expanding my work on the gauchos and continue exploring and documenting the cultural richness of Argentina. I am deeply passionate about gaucho culture, and I believe there are still many stories to discover and share. I want to continue exploring different aspects of gaucho life and traditions, and seek opportunities to showcase this cultural heritage authentically and meaningfully.

Vicente Isaías is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026