Paradise and Promenades: Angela Copello In Conversation With Vicente Isaías

Buenos Aires, Argentina — Ángela Copello welcomes me in the midst of a busy day. The photographer leads me up to the second floor of OdA, the art gallery that represents her, where she’s helping an art handler wrap one of her diptychs from her EDÉN series that are soon headed to an exhibition. They’re larger than I imagined. As the diptych goes out the door, I notice Ángela has brought along a suitcase packed with books and portfolios. I can’t wait to get my hands and eyes on them.

Sharing with someone whose career is as extensive as Copello’s is always a learning opportunity. A landscapist and photographer, I admire the passion and joy with which Ángela clearly practices and speaks about her craft. Over the years, Ángela has dedicated herself to photographing the contradictory beauty of nature, brilliantly capturing stunning photographs where branches and trunks give life to a whole range of questions and visions.

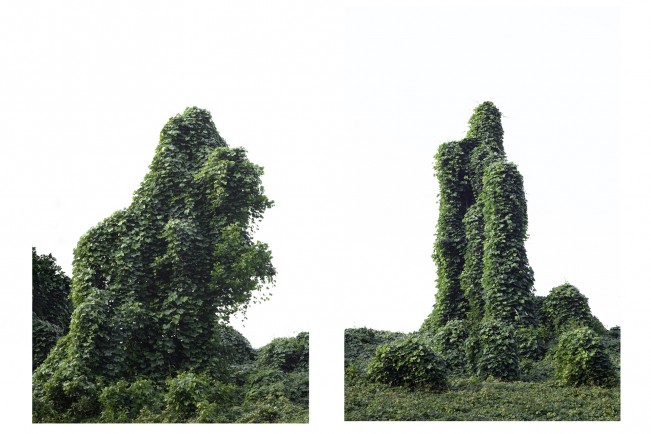

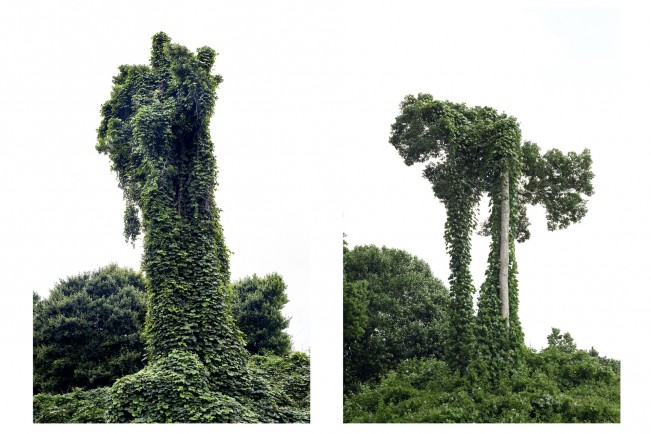

There is much to learn from her monumental photographs of nature, but just like in nature itself, one must pay attention to observe its details.What do I see when I look at her photographs? Some harmless ivy? A poisonous one? An apocalyptic or rather heavenly future where nature covers every human structure with its branches and petals? During our visit, Ángela explains to me that what I see are eerie and saltified tree graveyards, and that the greenery I enjoy so much are invasive species whose photographs serve as majestic, idyllic, even sinister portals. Observing the contradictory beauty of invasive species, portrayed so large and imposing before my eyes, fills me with a great anxiety for which I have no words.

In the last installement of Argentine Week, I sat down with Copello, a delightful artist and human being.

Ángela Copello. Photographer and landscapist. With experience in the realm of nature, her work primarily unfolds in that habitat. She lives and works in Buenos Aires. Since 1990, she has worked as an independent photographer. Her work has been exhibited in various collective and solo shows, nationally and internationally, including CCRecoleta, La Usina Boulevard Saenz Peña, Fundación Cassará, CCBorges, Palais de Glace, Nikon Gallery, Foto Fest in Santiago de Chile, and Foto Fest Mumbat at the Museum of Fine Arts in Tandil and the Stock Exchange. In 1999, she published her first book “Argentina, Parks and Gardens” with Ediciones Lariviere, followed by “Children of the Sun” and “Argentinian Landscapists.” A finalist in Felifa with her work “Impermanencias – Costanera Norte,” in 2017, it was published with the support of Patronage from the city of Buenos Aires. Selected twice for the National Salon, she was part of the first Imaginary Project Workshop. She participated in BAphoto 2017/2022 and Photo London 2020. In 2022, “Faces” as part of the “Ageless Beauty” project, received recognition of Cultural Interest from the Legislature of the City of Buenos Aires. In 2022, she was selected for the AAMEC Award – Caraffa Museum, Córdoba. In 2022, “Sacred Nature” – OdA Art Offices. In 2023, she exhibited alongside 50 artists at the Museum of the Rómulo Raggio Foundation. In 2023, “Mindescape” – Praxis Gallery. In 2023, “Unveiled Landscapes” – OdA Art Offices. In 2024, “The Power of Limits” – ZONA MACO – OdA Gallery. Art Residencies at Arte en Origen, Cantabria led by Andrea Juan, and Wabi Sabi Delta, Tigre. Represented by OdA Art Offices Galleries, Buenos Aires, Praxis, Buenos Aires, and Foto Arte Space, Uruguay.

Follow Ángela on Instagram: @angelacopello

Argentine Week featured artists from top left to bottom right: Santiago Porter, Juan Cruz Olivieri, Javier Bertín, Valeria Sestua, Angela Copello, Karen Navarro, Julieta Christofilakis.

Vicente Isaías: Great! We’re ready to start.

Angela Copello: Here is a book for you. This one is a bit old, but I brought you this other one as a gift.

VI: Oh! Thank you so much. I love your work. I was looking at it before coming here.

AC: This is one of my earlier works. It was one I cherished a lot.

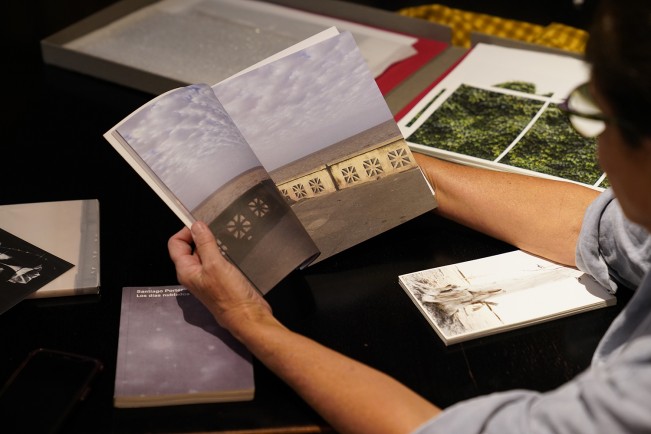

Ángela Copello looking at her photo book, Impermanencias, at Galerías OdA, Buenos Aires. © Photo by Vicente Isaías.

Ángela Copello looking at her photo book, Impermanencias, at Galerías OdA, Buenos Aires. © Photo by Vicente Isaías.

VI: I’m fascinated. Capturing the same place at different times. What is special about this particular place?

AC: This is our riverside along the river in front of Aeroparque. It doesn’t look the same anymore because I detest our leaders who decide that everything modern is better. They have renovated almost everything, including this railing that was over 100 years old and very useful for fishermen. Now they have changed its structure, turning it into something useless. But well, this corner. At that time, I lived downtown and it was my route to and from work. I worked as a landscaper for many years and most of my projects were in the northern area. So, I would pass by here at different times of the day. I dedicated myself to photographing the riverside for more than two years.

VI: This entire series was taken over two years, in the same place. The consistency and precision in this, placing the tripod with millimetric accuracy.

AC: I had the place marked, with the same focal distance and height. Although there are some differences, of course. And I have a large number of photos from that period. Then we made a selection and these were the chosen ones.

VI: When I saw the work online, I thought all the photos had been taken in a single day, due to the way they are organized in the book. It’s interesting how you play with the perception of time.

AC: Let me show you something that no one notices. Behind each page, there is a hidden page that details the date the photo was taken, along with a sky color of that day. It’s a detail that the graphic designer, who in this case was my daughter, and I incorporated as a game, although I know it goes unnoticed by most.

Detail from Impermanencias. The date and time of each photograph is hidden between the pages of each photograph.

VI: Those are the little things you discover over time, after years of having the book. Sometimes, you don’t notice them right away, but they enrich the experience. How was the process of recording the date and time of each photo?

AC: Keeping that record was straightforward, as it was a digital image. I don’t keep a diary in the traditional sense, but I have many notebooks where I jot things down.

VI: You started with film photography, now you work in digital. What was it like experiencing that transition?

AC: I am 63 years old and digital started in 2000. I had the lab at home, my daughters when they were a bit older, I had all the time in the world, I didn’t have to work or was married and was supported.

VI: Do you still photograph on film?

AC: No, not anymore. I still have all the lab equipment tucked inside a wardrobe, but I think I will not go back to using it. Sometimes I work on projects with silver gelatin and cyanotype, but most of my work now is digital. I like cyanotype because of its relation to botany, Anna Atkins, and all that.

VI: Indeed, speaking of which, where did your interest in botany originate?

AC: Actually, my mother loved it, but we lived here in the center, and on a balcony, she managed her little pots. My grandmother had a house in Córdoba, in the mountains, and there was a lady who worked all her life as a gardener at my grandmother’s house, from when I was born until the house had to be sold due to financial issues. She was a true plant lover. My grandmother was very strict and wouldn’t allow her to have hydrangeas, for instance, because of the belief that women who had hydrangeas wouldn’t get married. So, this lady, whom I admire a lot, would hide them in a spot where my grandmother couldn’t see them. (laughs)

VI: (laughs) A rebel! So, she inspired you as well.

AC: Yes, that was a bond I had with her. My grandmother’s house had a vegetable garden, and we would eat all the salads that came from there. All of that was wonderful. I lived in the city center for many years and at the age of ten, I moved to the countryside. So, for me, having plums, lemons, and all that is a heritage from her.

VI: So botany remains in your life as a landscaper and also ends up in photography, but where does that interest in photography come from?

AC: My father. He was a great photographer and an engineer. He was dedicated to photography, worked for the oil company ESO, and for a while photographed for gas stations. He was very fond of car racing, so he would go to road racing events. In my childhood, the memories I have I think are more from the photos my father took than from my own memories. He also had his studio at home. We would develop slides that we watched a lot on Saturday or Sunday afternoons, especially in winter. We are a small family, six siblings, but I only have four cousins. We’re not an extended family. We would gather a lot at some aunts’ houses, and he would bring the projector and I still have his screen and blog and we would go through there, watch the same and back in the same photo.

VI: So your approach to photography was through your father.

AC: That’s right, when I finished school and told him I wanted to dedicate myself to photography, he told me to use it as a hobby so as not to tire of it. And there I started to study advertising. But well, financially we were not well off. So I had to work eight hours and go to college at night and almost everything I earned was to pay for college because my idea was not feasible at the state at that time, so in the second year I said this isn’t a life for me and I switched to studying agronomy.

Ángela Copello looking at her portfolio EDÉN, at Galerías OdA, Buenos Aires. © Photo by Vicente Isaías.

Ángela Copello getting ready to ship her works from the series EDÉN, at Galerías OdA, Buenos Aires. © Photo by Vicente Isaías.

VI: Let’s talk about your photos of nature now. How do you decide which landscapes to photograph? Is there anything particular that catches your attention about a place when you decide to take a picture of it?

AC: I photograph a lot, however, there are certain aspects that tend to capture my interest and lead me to choose the places to photograph. One of the factors that attract me are landscapes that remain practically untouched despite human presence. I am drawn to the sense of serenity and connection with nature experienced in these environments. I seek for them to have a certain timeless or evocative quality.

VI: I want to know what led you to work with diptychs and triptychs.

AC: Having more space for composition. I have the feeling of being, as if, immersed, enveloped within the scene. The format of diptychs and triptychs not only offers the possibility of presenting images on a large scale but can also enrich the viewer’s observation and allow for greater immersion in the artwork. It creates a sense of continuity that, by unifying the composition, generates a more integrated visual experience.

VI: And when did you start working with this method?

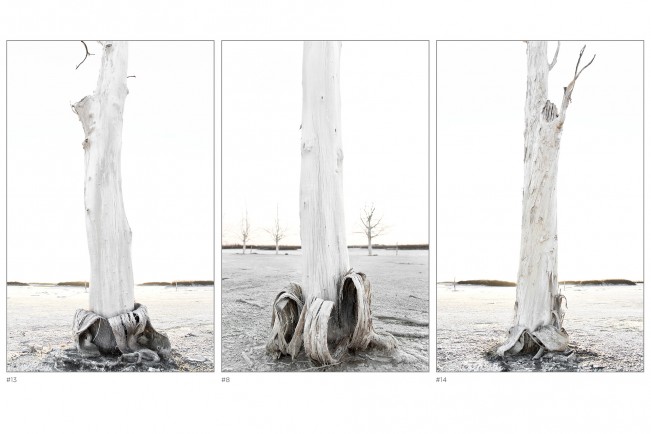

AC: Picture this: there’s this town, Epecuén Lake, nestled amidst a bunch of lagoons called the Encadenadas. But here’s the kicker – due to a mix of human slip-ups and Mother Nature doing her thing, the town ended up flooded. What happened was, they tried to fix a drought by diverting a river to fill up the lagoons. Seemed like a good plan, until unexpected rain came pouring down, causing a massive overflow. Now, imagine this spot was a hot spot, literally. Folks flocked here for the water, which was said to have healing powers, like the Dead Sea. But all this competition for tourists caused some real tension between the neighboring towns.

Flash forward 30 years, and you’ve got a town underwater, but traces of its past still linger. I met this lady who was just a kid when it all went down. The flood turned her life upside down, scattering her family and leaving a mark that lasted a lifetime. As time passed and the water retreated, what was left behind was this eerie scene – trees stripped bare, frozen in time by saltwater that turned everything it touched to stone. These days, those trees stand like ghostly guardians in the quiet emptiness. This whole experience left me haunted, in a good way. So much so that I’ve taken plenty of student groups out there to capture that eerie silence through their lenses. It’s a journey that stretches 700 kilometers across Buenos Aires, showcasing both tragedy and natural beauty. For any photographer looking to tell a story of transformation and resilience, it’s a goldmine.

VI: That’s a fascinating atory. I also love the details in these photographs. It’s almost like portraits of trees. Those details at the base, especially how the bark conglomerates and each one is very beautiful and different. I love the stark difference between the dry and the destructive.

AC: So, well, that was the idea. Well, when I finished this work, my fine art career kind of started. It was like a first letter of introduction to present myself. Not just as a photographer who could take pictures of anything, but as this is my work.

VI: Distilling the essence of Angela Copello through your work, of course, and it has evolved, as we saw with the photos. Talking about evolution, you’ve been working on researching and photographing a kind of invasive, semi-woody vine in the United States, originating from China, Japan, and the Indian subcontinent. What initially motivated you to investigate the Kudzu species and its impact in the southeastern part of the country?

AC: Once again, I saw the opportunity for a project where the focus was on the interaction between nature and humans, highlighting how the uncontrolled expansion of this invasive plant can irreversibly alter landscapes that were once considered natural paradises. Through my work in the series KUDZU: The Power of Limits, I sought to capture this duality and explore the complex relationships between nature, humans, and invasive species. Each image in the series reflects the struggle between beauty and destruction, invasion and resistance, inviting the viewer to reflect on the impact of our actions on the natural world.

VC: During your journey through Georgia, was there any specific moment or place that helped you understand more about the invasion of this species?

AC: Kudzu is a plant native to Asia, gifted by Japan to the United States almost 100 years ago, where it has become an invasive species. Its rapid growth and ability to cover large areas have led to the colonization of vast stretches of land. While exploring these landscapes invaded by kudzu, I encountered an intriguing duality: on one hand, the surreal beauty of the plant in its voracious expansion, creating intricate forms and covering everything in its path; on the other hand, the sense of loss and displacement of native vegetation, leaving behind a transformed landscape. And the problem of land invasion where agricultural activity takes place.

VC: What has been your research process regarding this plant? Are there any specific data you can share regarding its impact on the environment?

AC: In the research process, it helped to have an interactive map of the State of Georgia where reports of attacks by the species are recorded. I also reached out to other photographers in the area who advised me on dates and places to visit.

VC: Do you have plans to expand your research on Kudzu or similar species in other affected states or regions?

AC: I am still amazed by the images I captured; I would really love to return to that area and explore more towards the East Coast. My plans are to finish shaping it, everything is very recent.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026