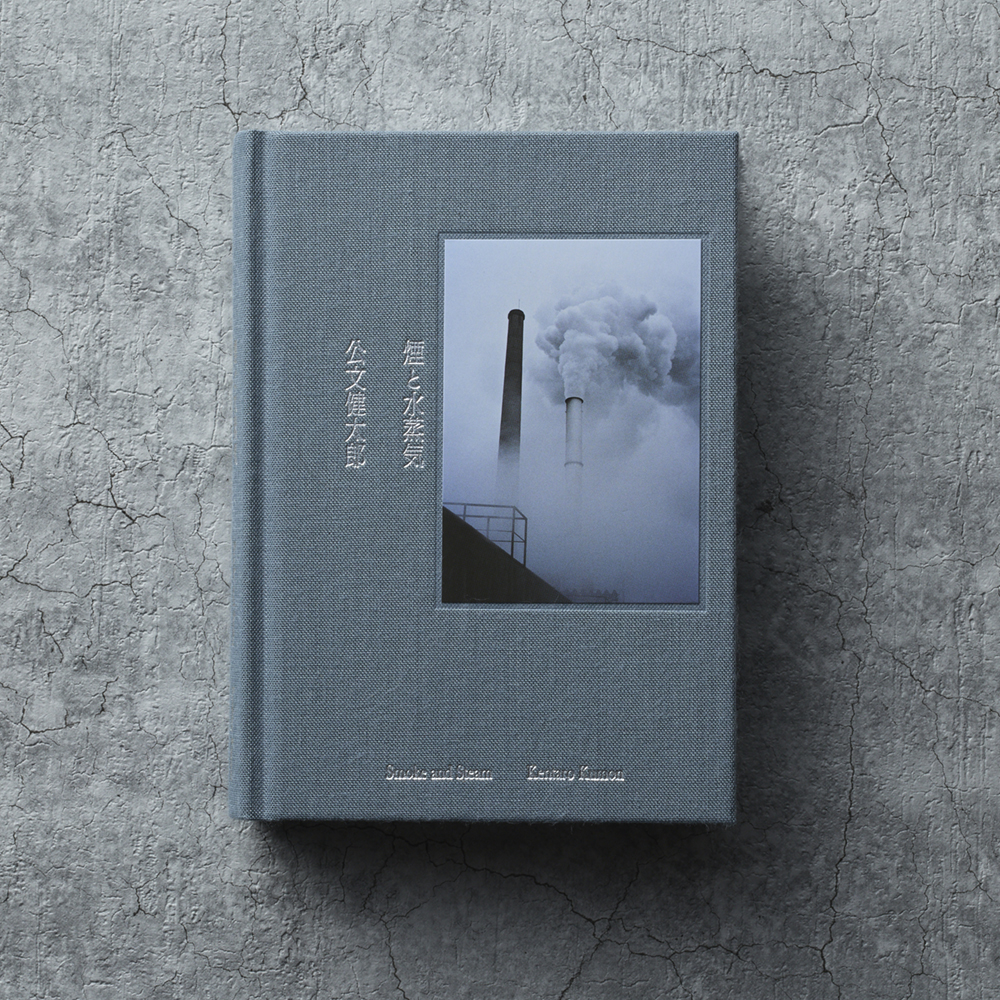

Kentaro KUMON: Smoke and Steam

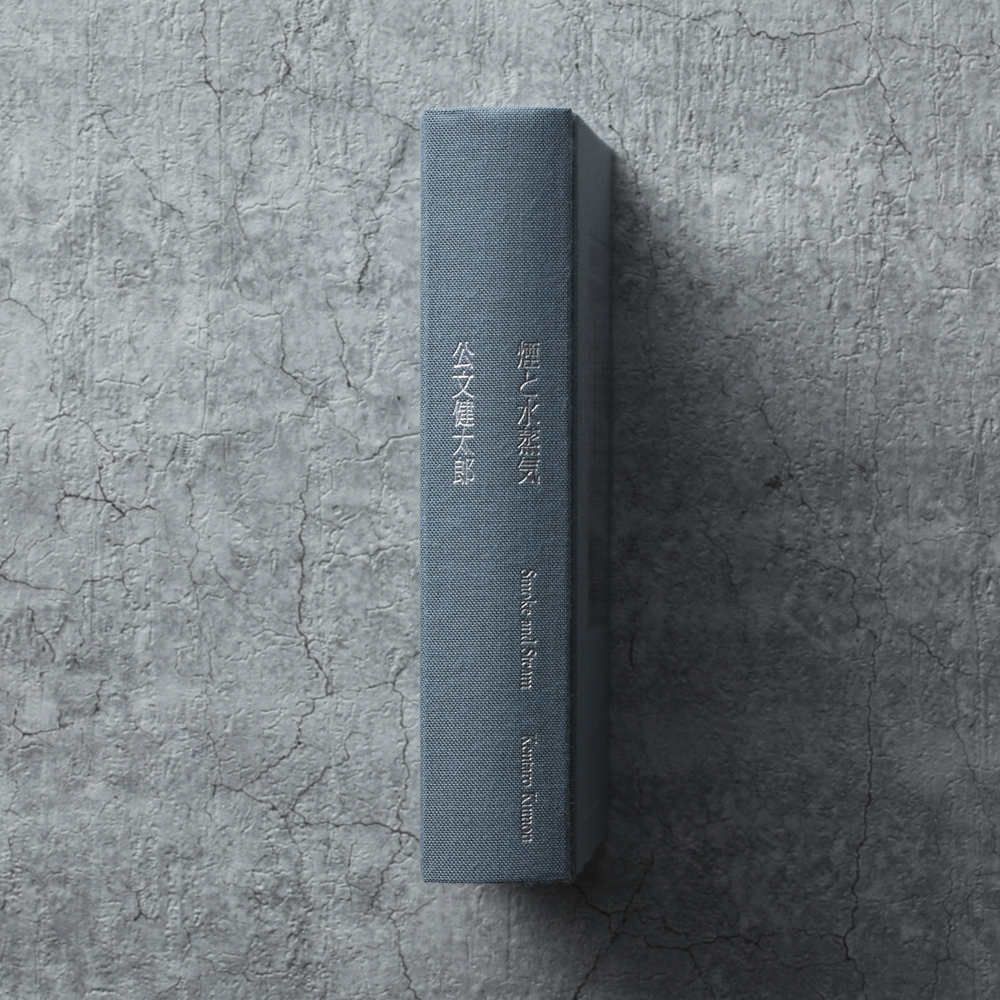

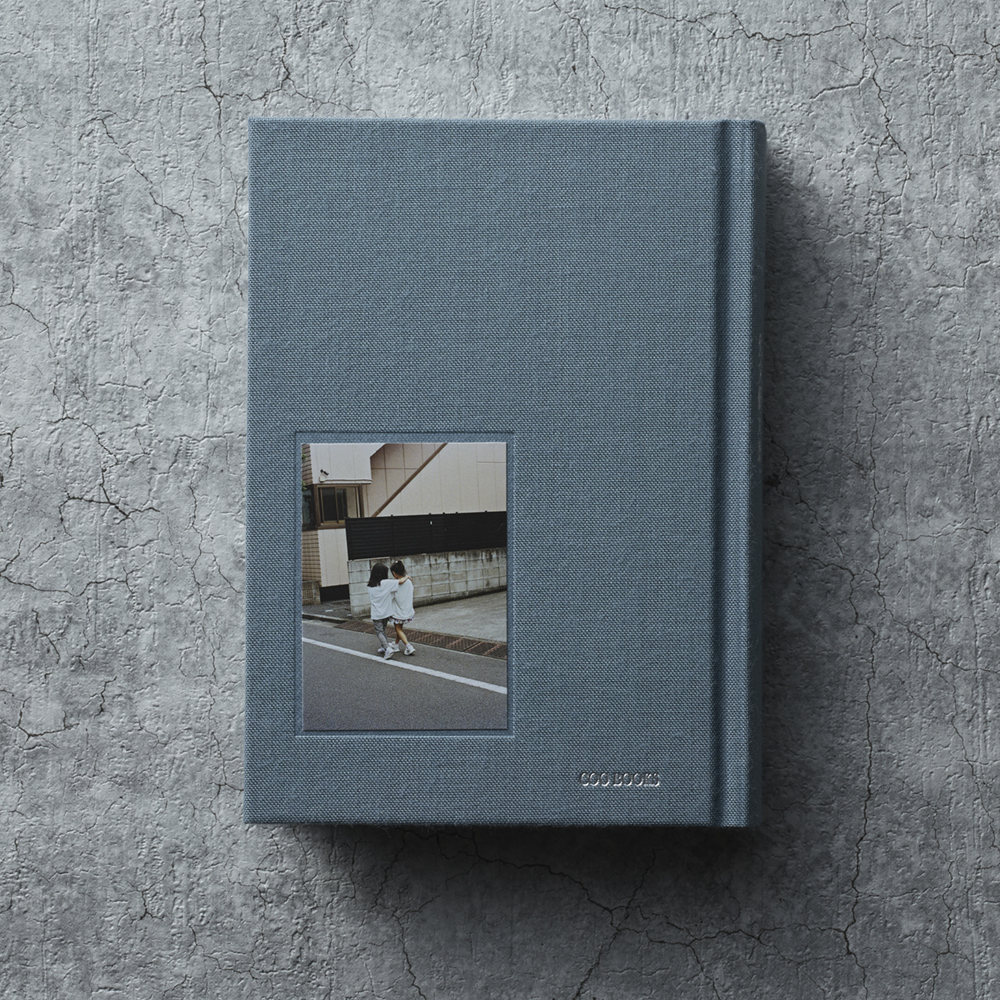

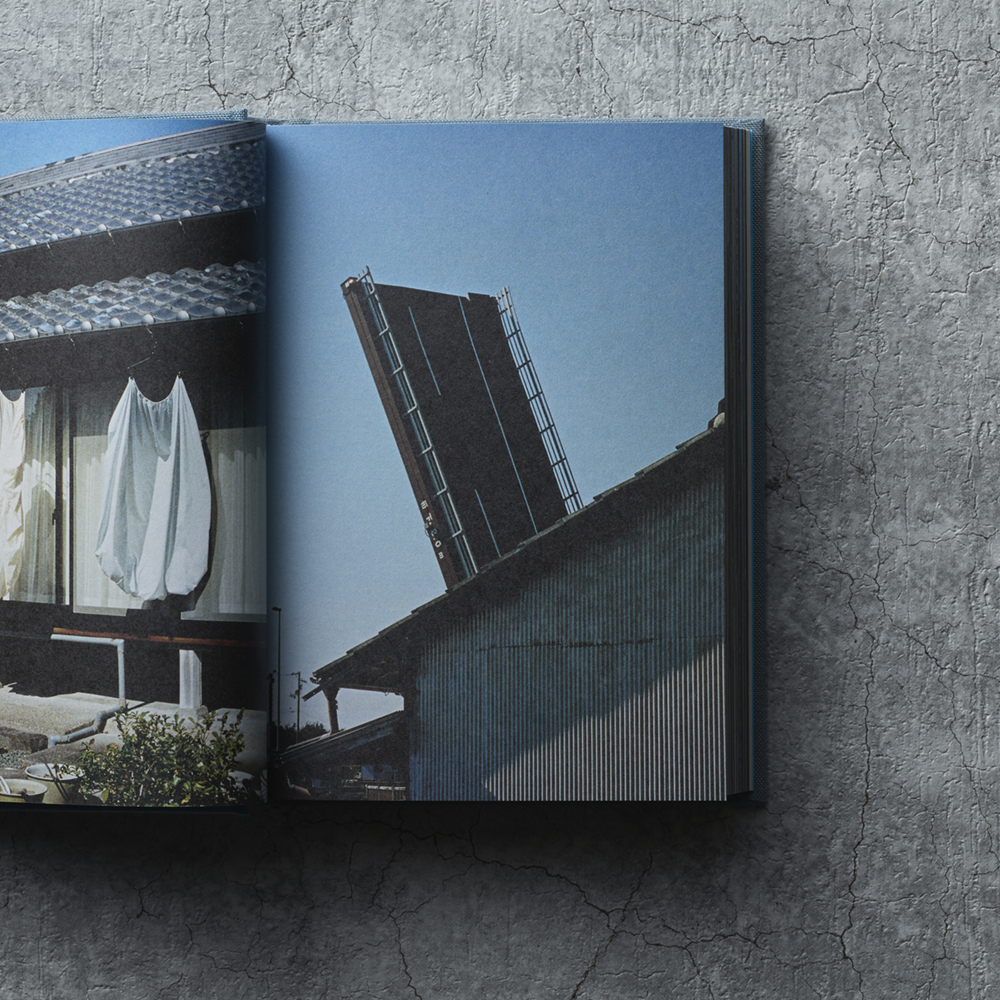

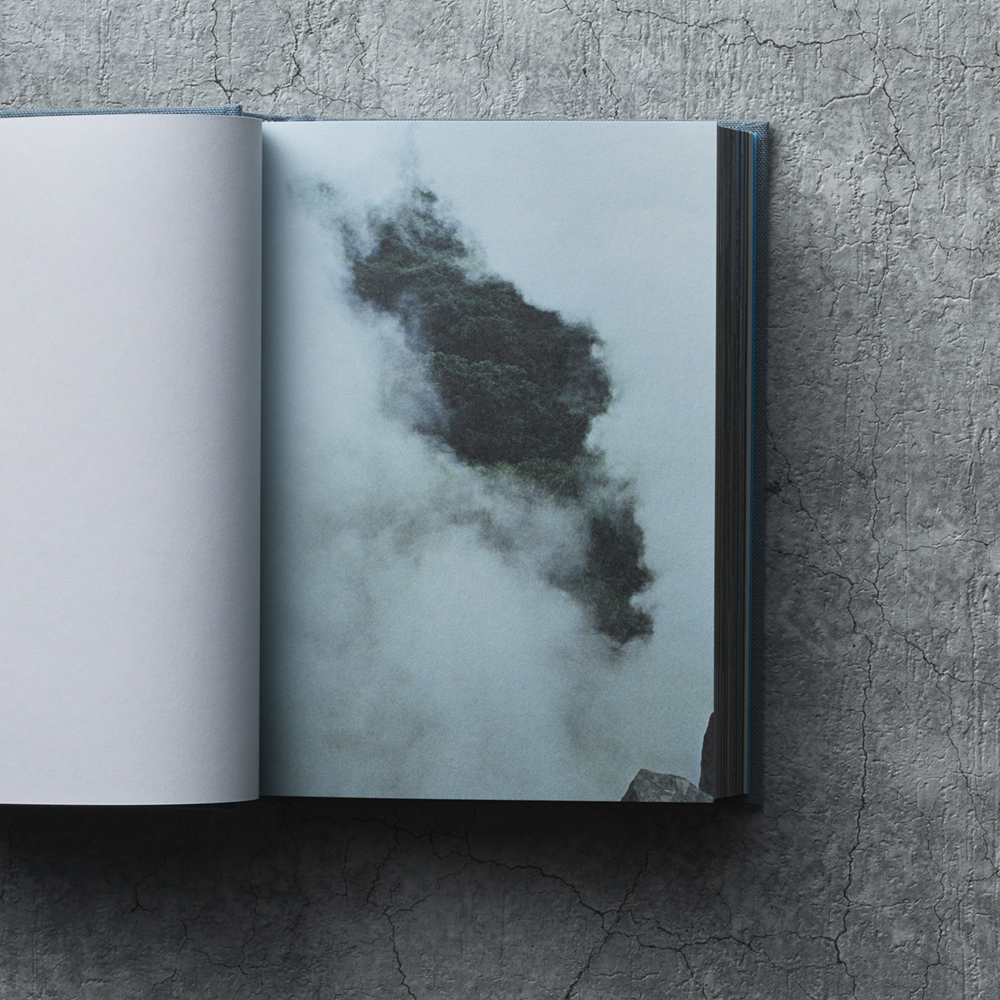

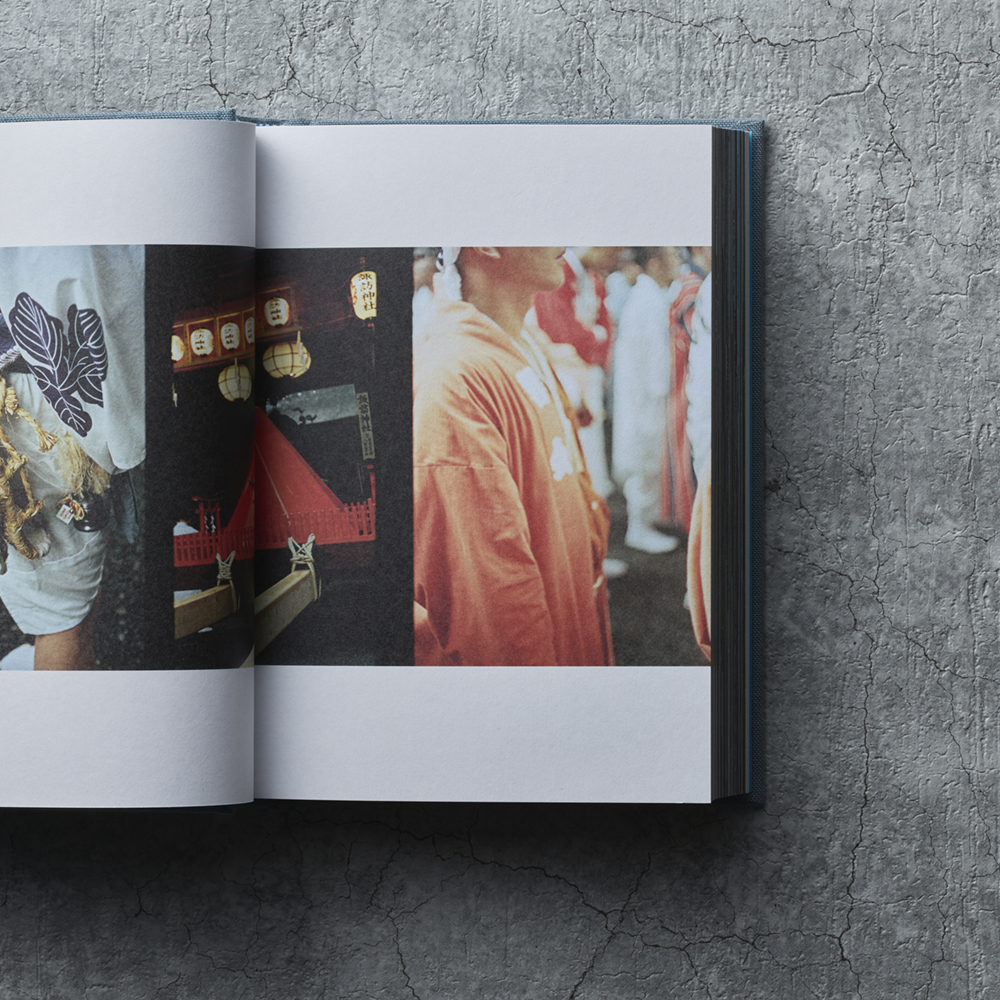

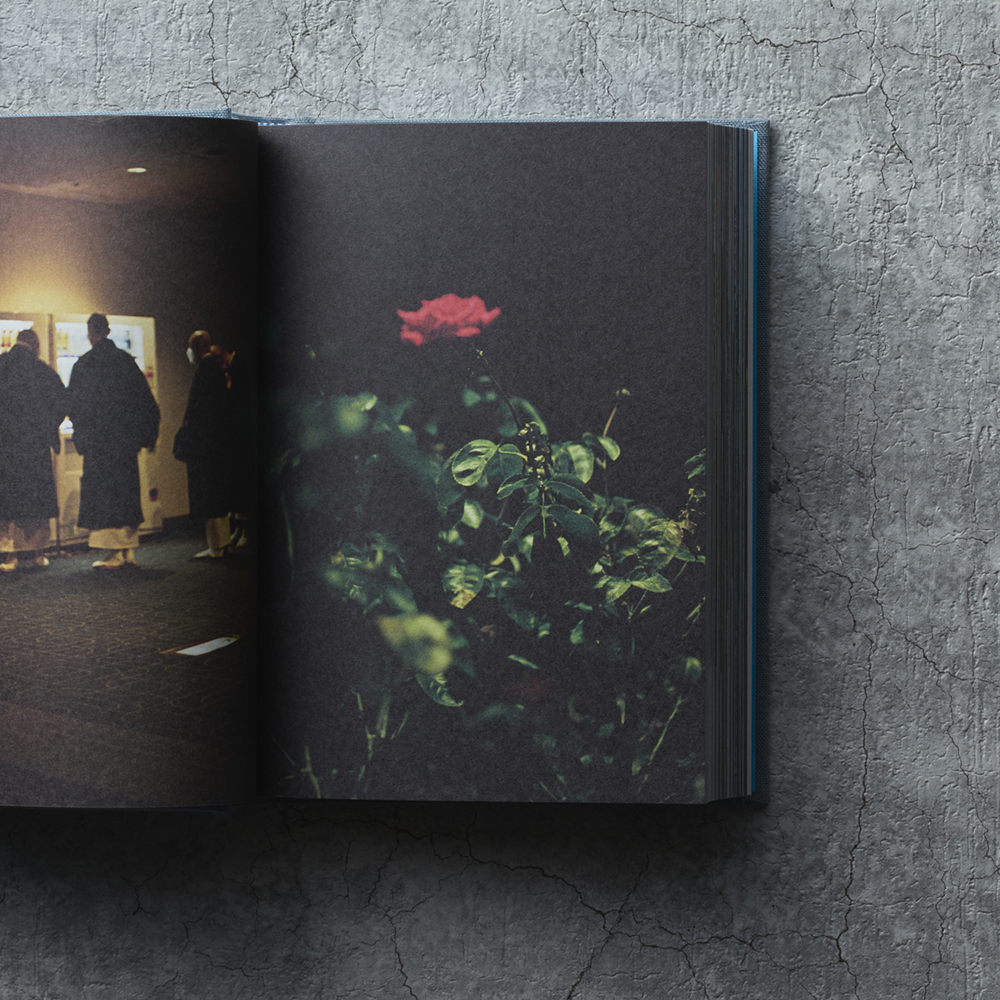

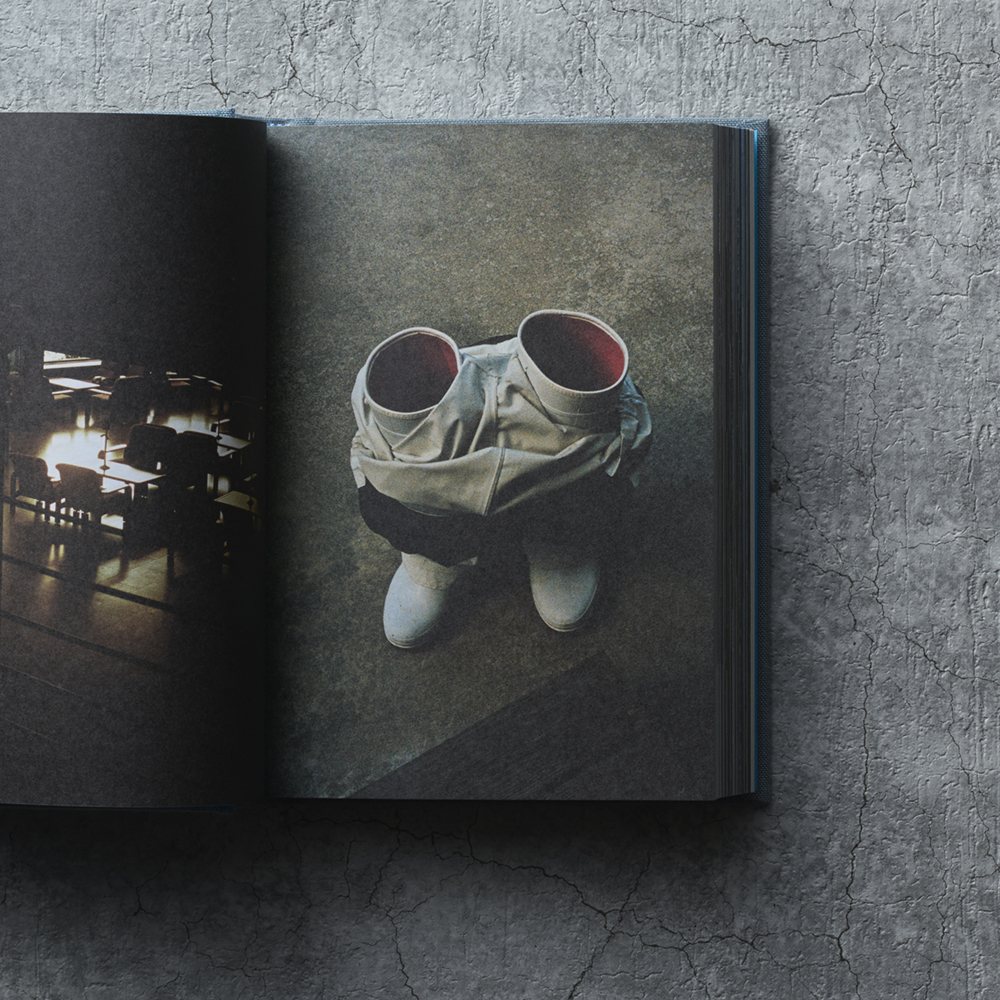

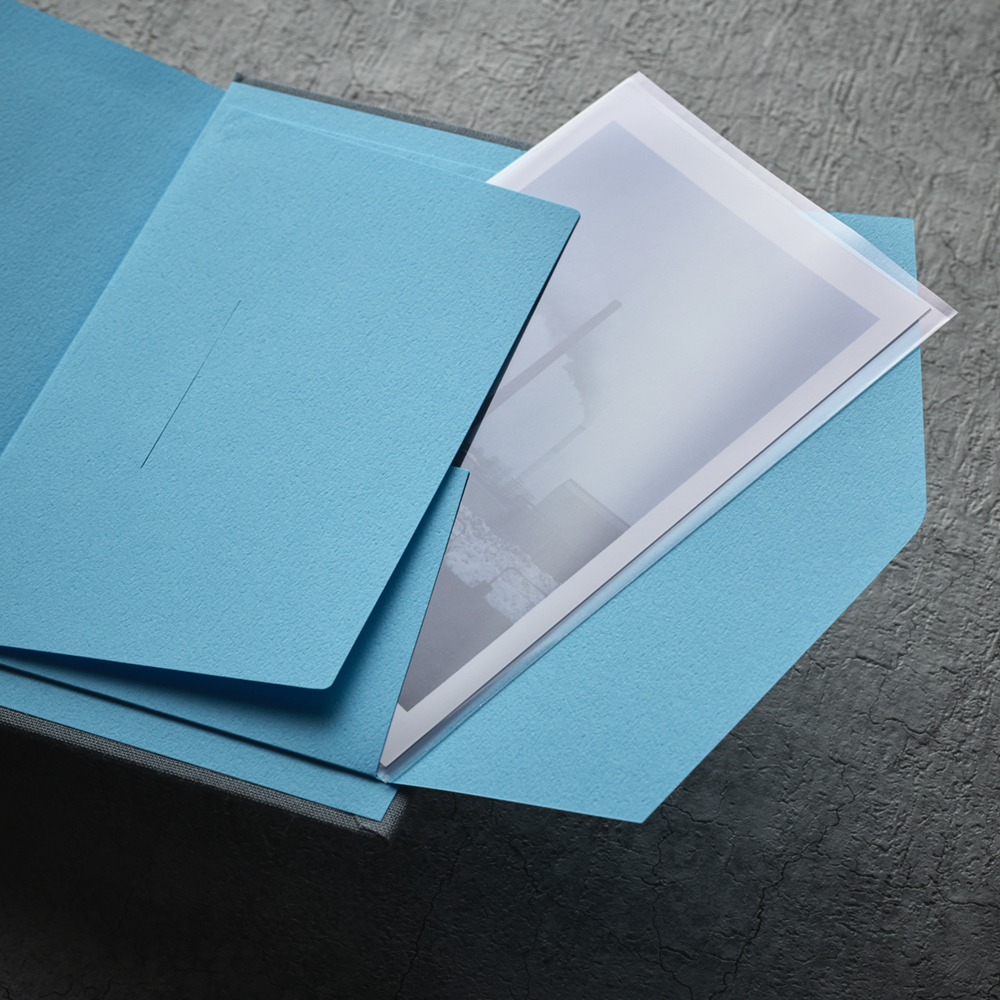

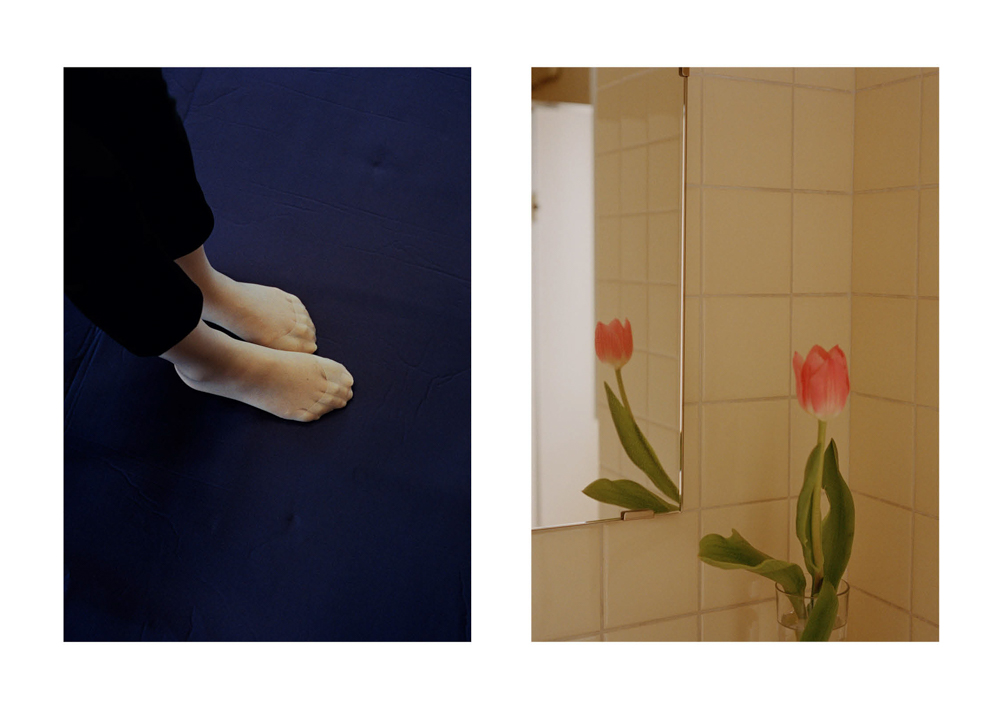

How do we memorialize a life? How do we chronicle our memories and our connections to our past? Japanese photographer, Kentaro Kumon, has recently relased a new book, Smoke and Steam, small in stature, but exquisitely poetic. The book is the size of a hand and is an homage to his father. I like to imagine the book as a bible of remembering, of beauty, of connection. It’s cover is wrapped in grey-blue linen with silver text, a humble skin that reveals page after page of diptychs that become a scrapbook of time and place. The book ends with turquoise end papers and a turquoise envelope holding one small image, to hold and consider.

Kentaro Kumon

Photographer. Born in 1981.

He photographs the front lines of primary industries and other places with the theme of “the point of contact between people and nature”.

His main works include “Tagayasuhito”, which photographs agricultural landscapes across Japan, “Koyomigawa”, which follows the connection between rivers and people, “Topography of Light”, which travels around peninsulas and photographs the climate and lifestyle of Japan, and “NEMURUSHIMA”, which takes as its theme the depopulation of islands. His latest work is “Smoke and Steam”, which is a collection of snapshots of his relationship with his father.

Instagram: @kkumon

Smoke and Steam

My father is sitting by the window, basked in sunlight and facing the sky outside. Maybe he is dozing or looking off into the distance or simply sitting there chasing a thought. The window in front of him takes up the entire wall of the living room. It’s the most striking feature of this house, which was built by my grandfather, an architect, and financed by my father, who took out a loan for it. In the distance, there’s a bridge stretching out into the sea.

Thereʼs a balcony, too, unusually large for a building of its time, where my mother keeps her plants. My father would often sit, without moving an inch, and watch her through the window as she waters her plants with a hose.

When it was no longer necessary to worry about Corona, I visited my parents’ house for the first time in years. It was odd seeing my father again. He had suddenly grown small and weak. I couldn’t help but feel not only sad, but also guilty, as if it was partly my fault, having told him to stay inside to avoid an infection.

He had always been a solemn, quiet man. Always deep in thought, difficult to approach. As a child I hesitated whenever I wanted to speak to him, unsure if now was a good time. Now the pensive, imposing father of my memories had turned frail.

As I watched him sitting by the window I thought back to the family vacations we went on in my childhood. My father in the driverʼs seat of the beige van, my mother next to him, and the three rows of seats behind them taken up by me and my two sisters as we drove on forever. Stretched out on my row of seats, I loved watching the outside world scroll by through the window.

There are two memories that will always stay with me about the things I watched through the car window.

Once I saw bright red flowers growing along the highway and asked my mother what they were called. “Oleander,” my dad said. “Theyʼre poisonous, you know. Every now and then a cow will eat too much of them and die.” I was so surprised and upset at that moment. Partly because flowers had always been my motherʼs expertise, but also because my fatherʼs remark terrified me. When I see oleander today, especially when they glow bright red in the sun, thereʼs still a sudden sense of dread coming over me.

The other memory is of seeing a lot of chimneys and smoke as we passed through an industrial area. Excited, I yelled for everyone to look. My dad said, “Thatʼs not smoke, Kentaro, thatʼs steam! Do you know how to tell the difference?” He explained, “Look where it leaves the chimney. Smoke is visible as soon as it comes out. Not so with steam. Steam is transparent at first, then turns white as the air cools it down. Look again, closely―itʼs steam!” My father rarely spoke to us children, and when he did, it was to tell us to hold our chopsticks correctly or to sit up straight or to hurry up. I loved hearing him explain something new to us and doing it with a kind of paternal pride. As a child, I was always impressed by how much he knew.

In 2023 I took out the old camera again for the first time in ages and spent every day of the year taking photos with it. I just kept clicking away, with nothing in mind in particular. Compared to the newer models Iʼm using today, my fatherʼs camera often didnʼt do as I wanted. The images would be out of focus or too grainy, or the film would tear altogether. But the photos it gave me made me wander back and forth through my memories, perhaps because I often thought of my father and our old house during that year.

photo & text: Kentaro Kumon

translator: Robert Zetzsche

edit: Yosuke Fujiki (Yosuke Fujiki Van Gogh Co., Ltd.)

design: Koji Miyazoe

publisher: Kentaro Kumon

published by: COO BOOKS

printed and bound by: LIVE ART BOOKS

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Eli Durst: The Children’s MelodyDecember 15th, 2025

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Kinga Owczennikow: Framing the WorldDecember 7th, 2025

-

Richard Renaldi: Billions ServedDecember 6th, 2025