Handmade Artist Books Week: Philip Zimmermann

I came to know of Philip Zimmermann from my mentor Susan Kae Grant. I got a chance going through his books in the CODEX in 2024 and was deeply fascinated with the content, thought process and designs of the wide spectrums of his works. Contemporary social, cultural, and political issues are depicted masterfully in Philip’s works. Each of the work shines with brilliance in the technical mastery of the materials, processes, craftsmanship and artistry.

I am honored and humbled to have this interview with Philip Zimmermann, an artist, an educator, and Professor Emeritus in the field of design and book arts.

Tell us about your growing up. You are an artists’ bookmaker and publisher and an educator for over 40 years. What made you shift from architecture to fine arts photography and then, choose book form to express yourself?

I am the son of a Cuban mother and a Foreign Service Officer, a US Diplomat, so I grew up overseas as what is called a ‘Third Culture Kid’ with no home country and never feeling part of any one national identity. I was born in Bangkok, Thailand, and my father was stationed in London, Brussels, Madrid, Lisbon, Barcelona and Washington DC. My parents encouraged me to follow my artistic inclinations by promoting a life as an architect, as they saw that as a viable way of making a safe yet creative professional career. Although I love architecture, I interned at an architecture firm one summer and decided that it was not for me.

I finished half of a five-year undergrad degree program in architecture, then transferred into a BFA program within the same university. Ever since an aunt gave me a small Agfa camera as a middle-school kid, I had always loved photography. I became serious about it in high school, buying two Nikon Fs and several lenses. My undergrad program in college did not teach photography or have any photo faculty, so I used photography in my silkscreen and other print projects. Robert Rauschenberg was a big influence on me at that time. However, I did keep making black+white fine-art-type photographs on my own.

After graduating and living in the South of France for a year, I applied to graduate programs in photography with the portfolio of work that I had created during that year in Aix-en-Provence. I decided to go to The Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, NY, studying under Joan and Nathan Lyons and Keith Smith. Artists’ books were an important medium and part of the core curriculum at VSW, and I started focusing on that while I was there, though I had made a couple of photobooks before I arrived in Rochester in 1976.

What drew you to artist books? How important is it to make hand bound books as opposed to mass production? What was the motivation behind establishing the imprint Spaceheater Editions?

I have always loved books and especially books that used the book medium creatively. When I was in high school in the late sixties, I bought copies of Andy Warhol’s Index Book, Marshal McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage and Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit, among other titles, many considered iconic artists’ books today. This interest became much more central to my own art making in graduate school, studying at the Visual Studies Workshop. Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover came out in 1975, I was blown away when I first discovered it in 1977, while in graduate school. Here was a book that used photography but in an entirely new way, using and exploiting the book form conceptually and as a time-based medium.

Most of my books are photo-based, but I don’t restrict myself to photobooks alone. I have had a long teaching career at universities, but despite the fact that I have an MFA in Photography, I have never taught in a Photography Department: always in a Design Department. I have taught photo-silkscreen, offset printing for designers, artists’ books, publication design, illustration and animation/motion design.

I am not very interested in one-of-a-kind photobooks or artists’ books. I like the editioned multiple. It doesn’t matter much to me if it’s hand-made as a small edition, or a larger edition produced by a commercial printer. I have made both. Several of my books were made in editions of 1000 in China, Korea, and at a commercial printer of binder here in the States. But I also make books in much smaller hand-bound editions with from thirty to one hundred and fifty copies. Some of the difficulties in making artists’ books and photobooks is cost and distribution. Many of the books that I make are not of much interest to the general photography book-buying public, so I try to only make as many as I think will easily sell in the space of a few years. It is not the usual business plan of most book publishers!

Although I had made a few books while in grad school, I knew that I wanted to publish and not only my own books but those of other photographers and artists who I thought were doing interesting work. While spending a semester doing a graduate internship at Chicago Books and taking a book-binding class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago while there, I happened on a manufacturer’s sales catalog at the school that somebody was using as collage material. It was for a company that made space-heaters. For some reason, the image of a spaceheater clicked in my head as a name for my new press. It was a play on the name of a famous artists’ book archive in New York called Franklin Furnace, plus seemed like a nice metaphor for a publisher who was trying to put out hot new books.

Your work tends to come from your personal experience of social and political issues. In your process, when does your work take a specific form of the book? How do you balance the relationship between the narrative and the form of the book?

I have always been interested in both personal and cultural politics. I am an unashamed progressive and tend to explore content that looks at society through that lens. But I am also interested in the way that my particular medium, the photo-based artists’ book, uses and explores the book form using both its structure and its narrative power. I don’t always have much text, but when it is used, it has to work hand-in-hand with the imagery or photographs. My books can seem quite different from each other, and that is because I approach each new project from what I hope is a fresh standpoint, hoping to explore ways of using the content to make a new, exciting and novel book.

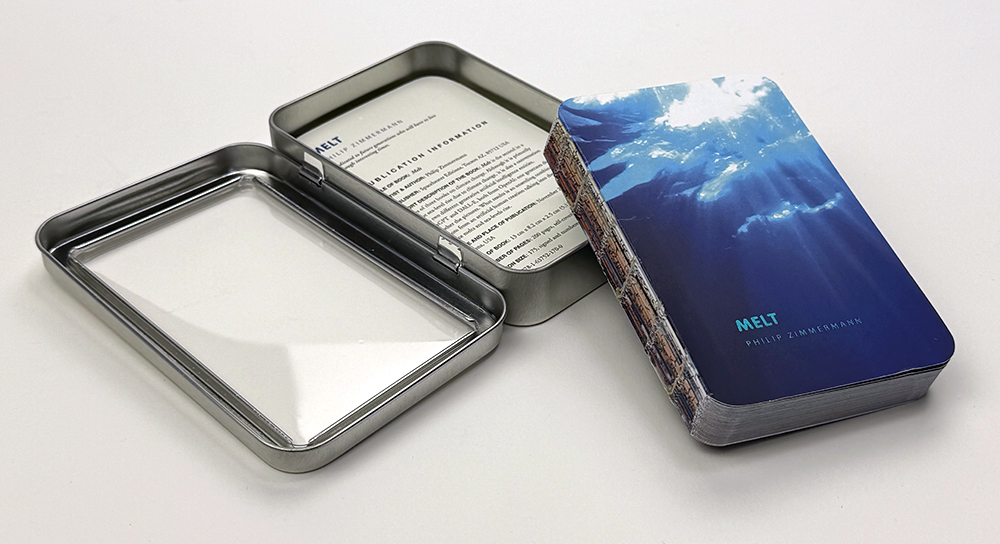

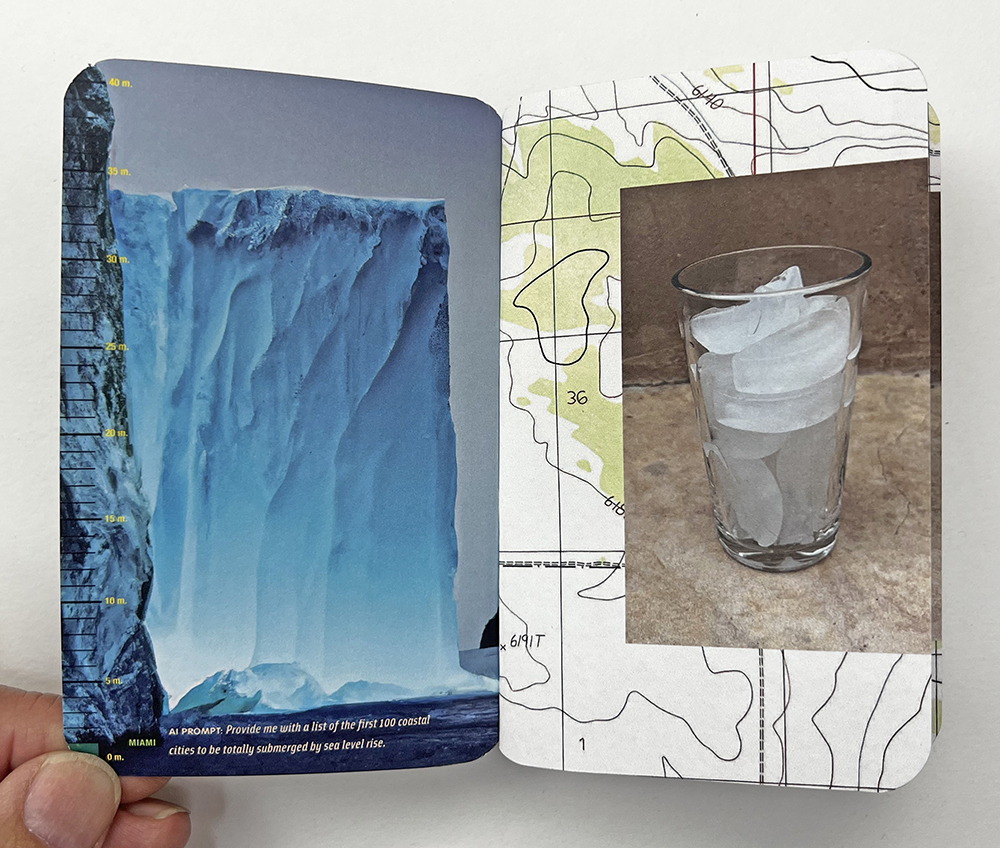

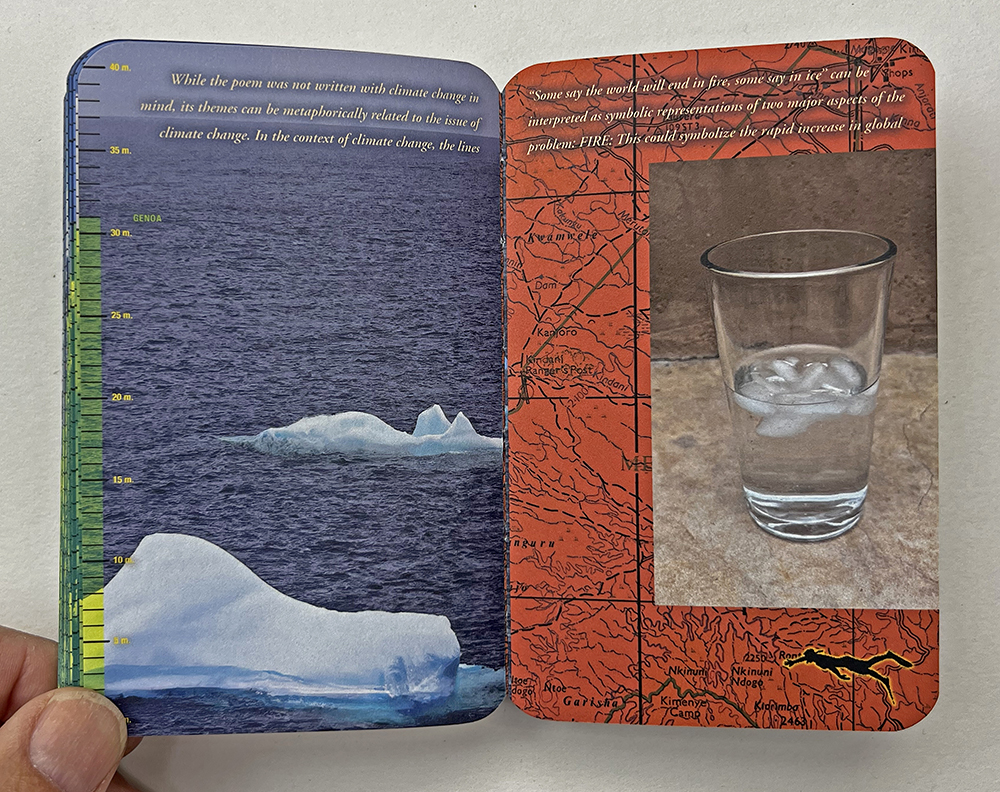

Can you tell us about ‘Melt’?

Melt was the second of four books on climate change, and specifically the subject matter in this one was sea-level rise. I had seen reports on the increasingly rapid rise of global sea-level from the melting of the polar caps, and it was happening far faster than was originally projected. It seemed that there were few attempts to arrest carbon increase to slow this melting. At the same time I was starting work on Melt, the first public versions of the AI programs ChatGPT and DALL-E, both from OpenAI, were released. Artificial Intelligence seemed as much of a threat as sea level rise, even though there a few people who think that the use of AI may become civilization’s salvation. Given the two potential threats to mankind, and one possible but unlikely remedy, I thought that an interesting way to create a book warning of sea-level rise was to use AI generated text and photos using various prompts. I included the prompts. The book has numerous devices to propel the narrative: flip-book images, a changing scale that shows sea-level rise in many global cities, lyrics to historical tune, and AI generated poems and so on. The book comes in a small metal box, which metaphorically protects the book from water. For a further, closer reading of Melt please refer to an article in Books on Books: https://tinyl.io/C4RW.

I am intrigued by the various print media and photo-mechanical processes you have been using for your books – manipulated CMYK, halftone with inkjet, screen printing, HP Indigo, offset.

When I was in graduate school at Visual Studies in Rochester, I became very involved with both photo-offset and photo-silkscreen. In those pre-digital days, the translation of a continuous-tone photographic image to one that can be printed, required the use of halftone dots using screens and lithographic film. I spent many hours in a photomechanical darkroom making the halftone film for both offset and screen printing. Part of my thesis project was a large portfolio of portraits of manipulated halftones called Portrait Constructions. While in grad school I had trained with a German color separator in Rochester, who taught me how to make optical color separations, a tricky process. Later, when I was working at an artist’s print shop in Rhinebeck NY called Open Studio, I did a lot more experimenting with various ways to use both regular and stochastic halftone dots. Looking closely for many years through a magnifying lupe at various angles and sizes of halftone dots in lithographic negatives on a darkroom light table gives you many ideas. I continue to be fascinated with halftone dots and patterns, but of course now I use digital means to arrive at them.

How do you decide which media to use for a particular book?

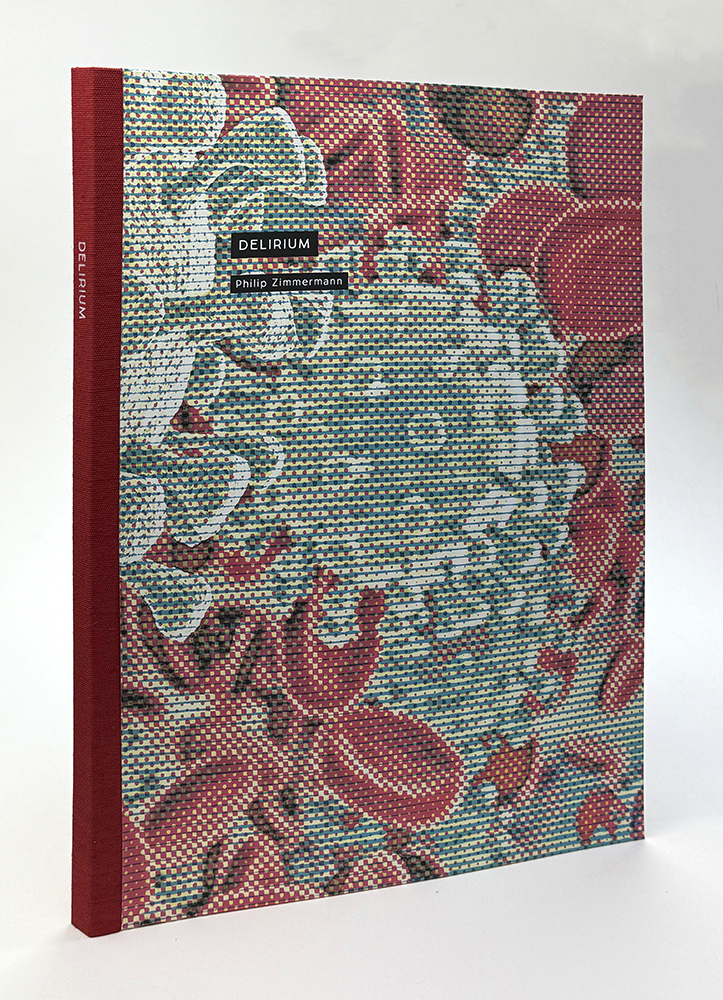

I tend to use whatever media that I have available to me when I am making my books. During my graduate school years and while I was teaching at Purchase College SUNY, I had access to offset presses, so that was the medium that I used. Offset lithography is great for larger runs, usually over 500, but doesn’t make as much sense if you are not printing yourself –and the edition is much smaller. I tend to use HP Indigo or other digital printing technologies now, since they are accessible and relatively cheap for smaller runs. I have even used archival pigment inkjet for small editions. My book Delirium was all inkjet printed, in an edition of 30. Inkjet ink is very expensive so although the quality is very high, one has to consider the consumable costs too. The same goes for binding methods. Small runs can be hand-sewn and hand-bound, larger runs are smyth-sewn in a commercial bindery. I have also used offset printers in China (Sanctus Sonorensis) as well as Korea (Long Story Short) as well as regular local commercial printers here in Tucson.

I see a wide spectrum in your work – from ‘Alphaville’ to ‘Ojala’, ‘Melt’, ‘Delirium’ ‘Anthropocene’ and to ‘Swamp Monsters’. Each was stirring different feelings in me. Can you elaborate your emotions behind these works?

I react to personal feelings about what is going in my own life, what is happening socially and politically in our national scene, and globally. The conceptual content of my books seems to spring up as ideas quite organically. Sometimes they come from the general zeitgeist, sometimes from something I have read, sometimes just from how I am feeling at that point in my life. I tend to assume that whatever feelings I have about any subject matter tends to be more universal than just about me, and are felt by many other people. I’m sure some books work better that way than others.

Who are your inspirations in artist books?

I have quite a few. Many of Keith Smith’s books, especially the early ones from the 1960s; books by Dieter Roth, Peter Beard, Michael Snow, Ed Ruscha, Karel Martens, Sophie Calle, Paul Graham, Peter Malutzki and his partner Ines von Ketelhodt, Clifton Meador, many others. Some are photographers primarily, others are artists using the book form but are not necessarily photographers, others are amazing book designers working with photographers, like Irma Boom and Hans Gremmen.

Artist books by Philip Zimmermann

A few favorite works chronologically, with short descriptions. Please check the website for more.

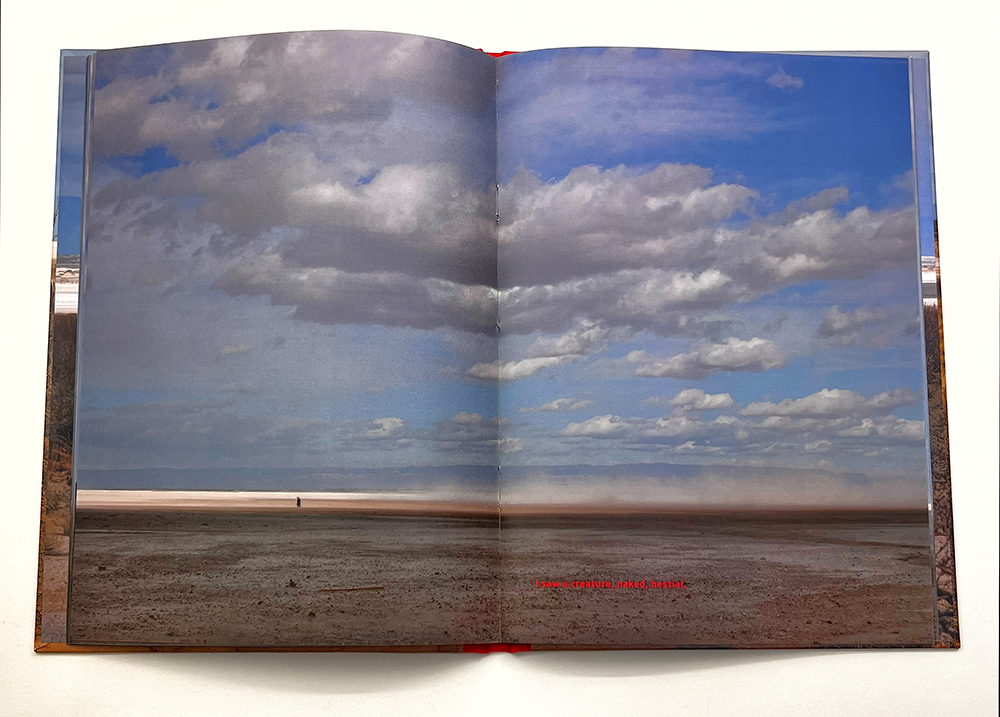

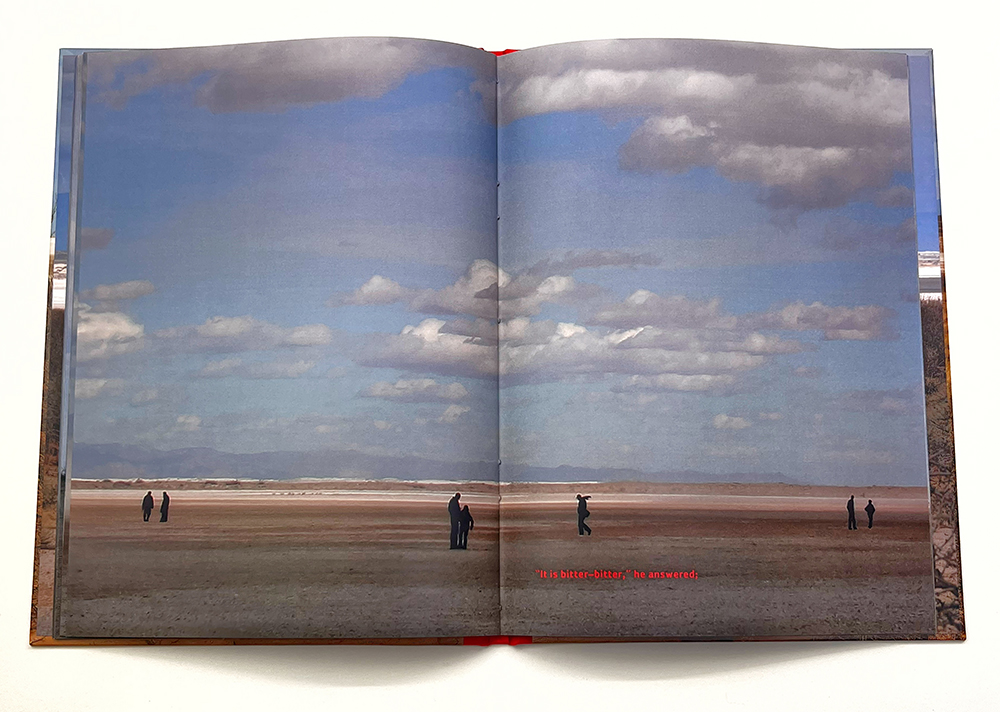

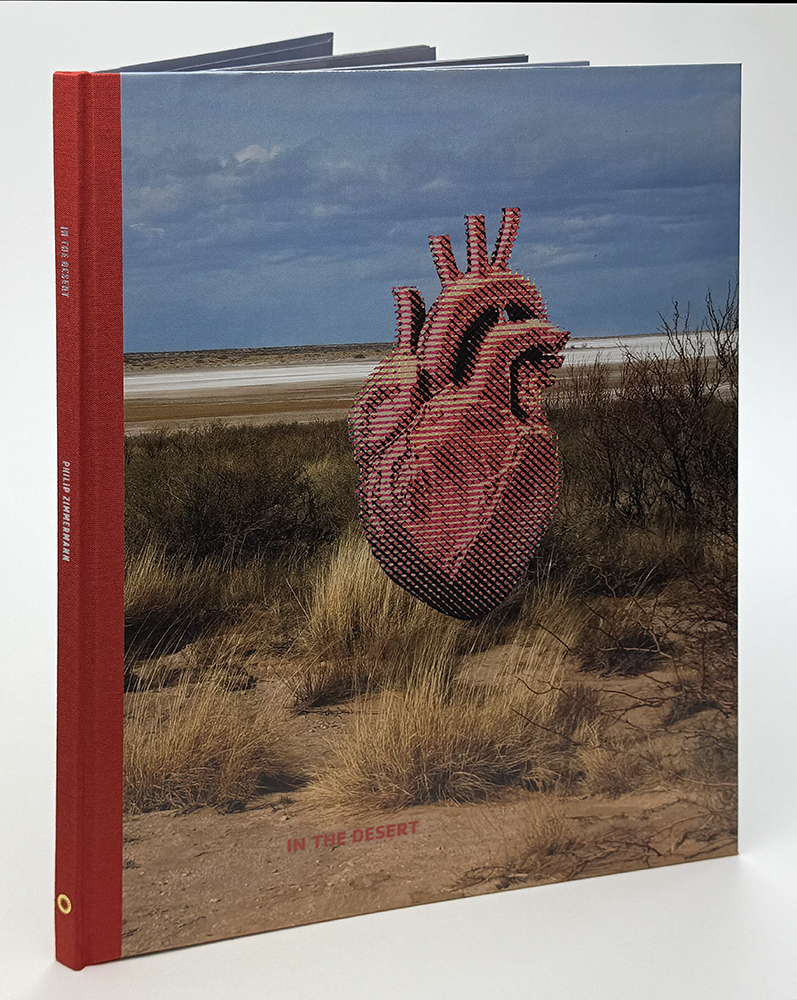

In the Desert (2024)

The last of four books on climate change. This one uses a short and dark poem by Stephen Crane to suggest the predicament of mankind: that we as a species know that our behaviors are destructive to the planet, but we cannot help ourselves and pull ourselves out of our self-destructive and self-absorbed actions. Is human nature inherently selfish, sinful, and corrupt? https://spaceheat.com/books/desert .

Melt (2023)

The second of a quartet of books on climate change. Although it is primarily about sea-level rise due to climate change, it is also a conversation with two different generative AI entities, ChatGPT 3.5 and DALL-E, both from OpenAI: one generates the text, the other the pictures. What results is an unsettling combination of wisdom from an artificial human creation talking into the void as the ice melts and sea levels rise. https://spaceheat.com/books/melt .

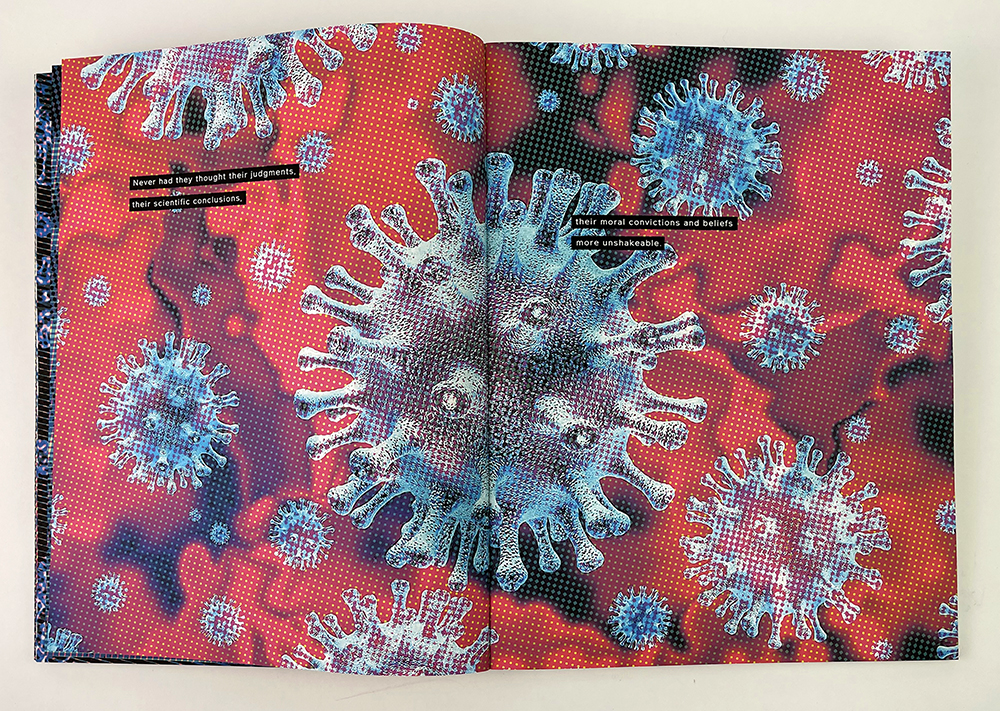

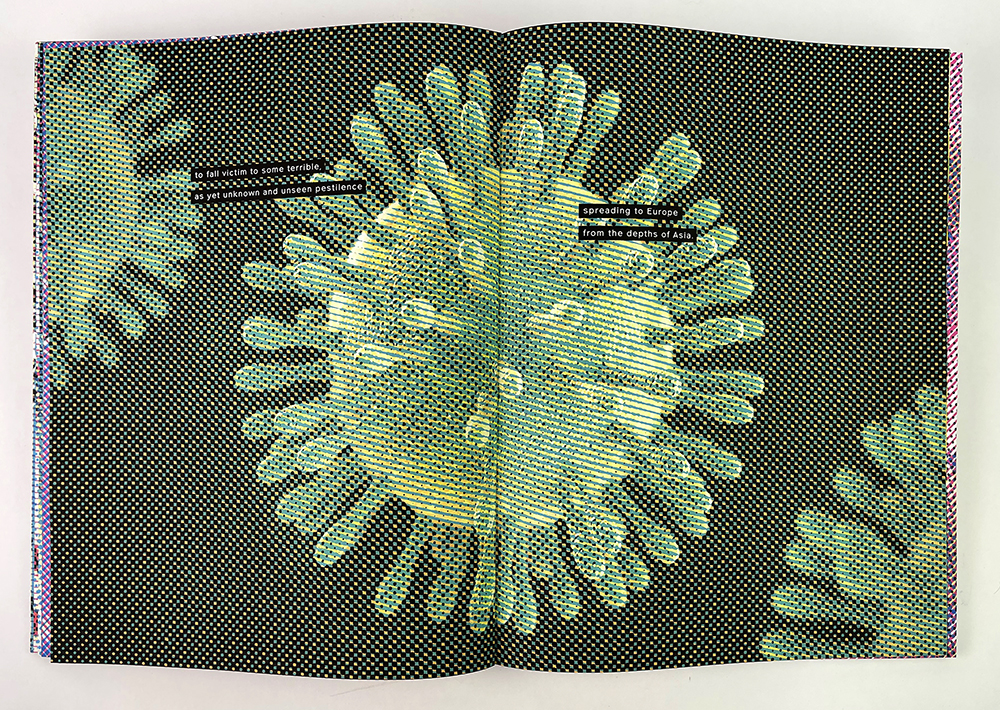

Delirium (2020)

This is a book born of the great Covid-19 pandemic. The images are enlarged images of the virus, the prophetic text comes from Raskolnikov’s fever dream at the end of ‘Crime and Punishment’, written in 1866 by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The atomistic halftone treatment of the large viral illustrations attempts to mirror the scientific deconstruction and disassembly of the coronavirus in order to develop a critically important vaccine. https://spaceheat.com/books/delirium

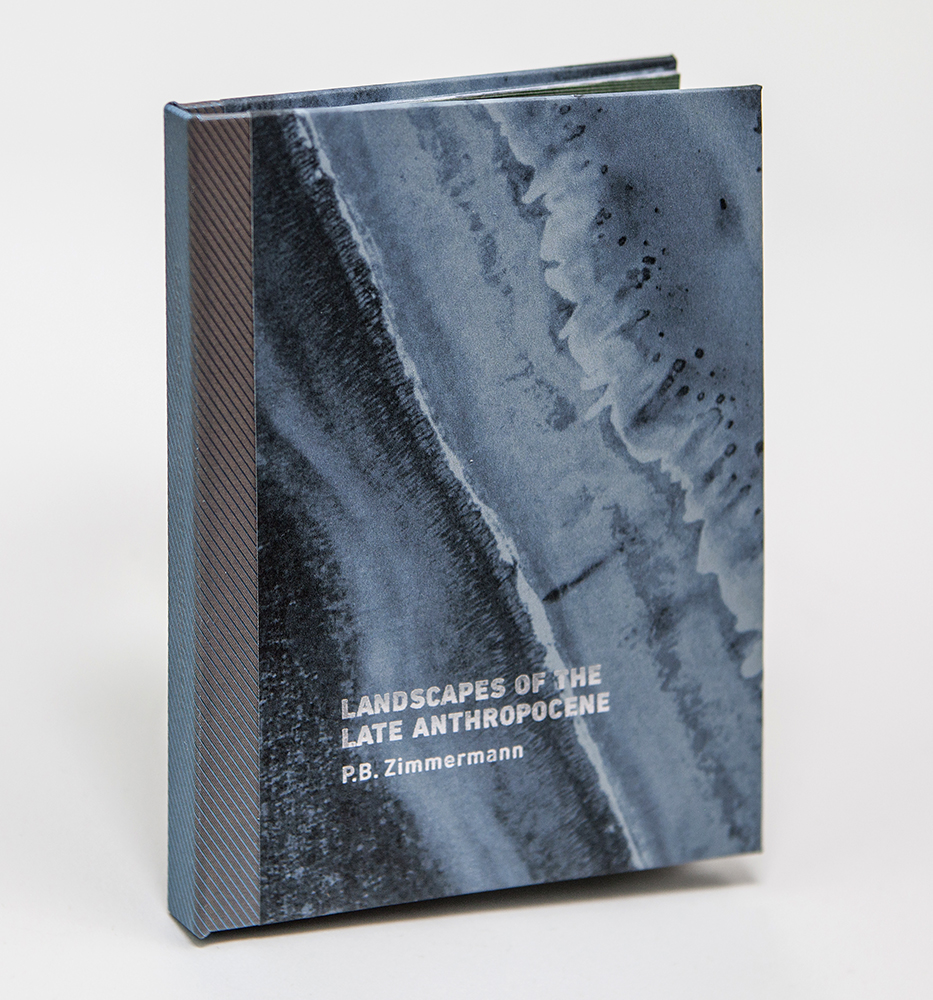

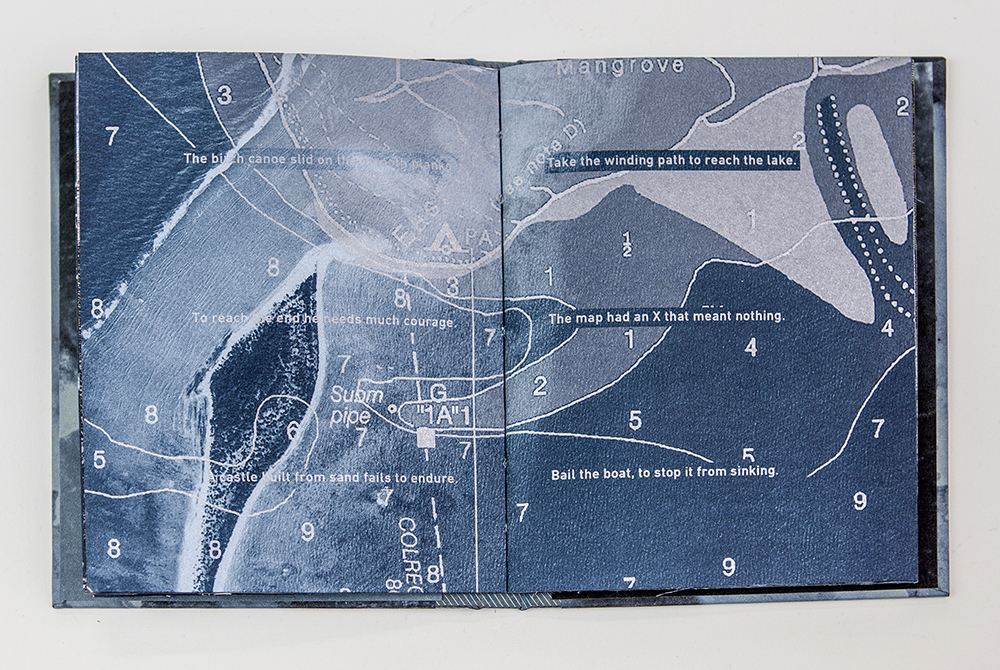

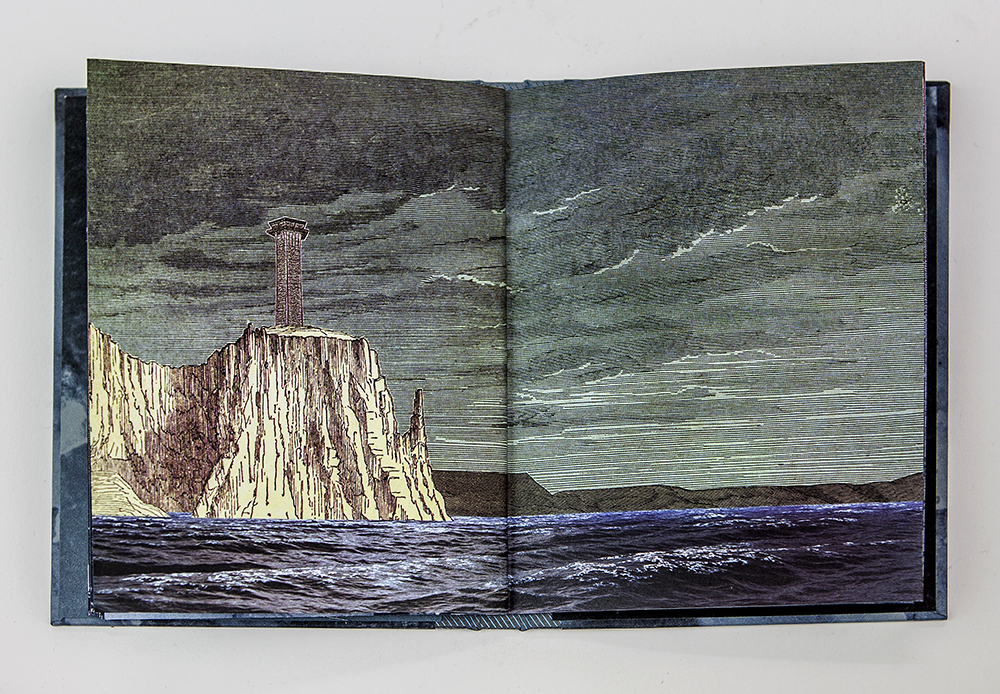

Landscapes of the Late Anthropocene (2017)

The first of four very different books on climate change. A dystopian set of images that hint at a future watery world, one where the remnants of civilizations live in armed and guarded towers, growing their food in vertical farms inside these towers. The rest of the world’s population have mostly died off. Marauding remnants exist in small groups that would try to gain entrance into these armed tower structures. The images are collages of my water photographs with 19th century steel engravings. https://spaceheat.com/books/anthropocene

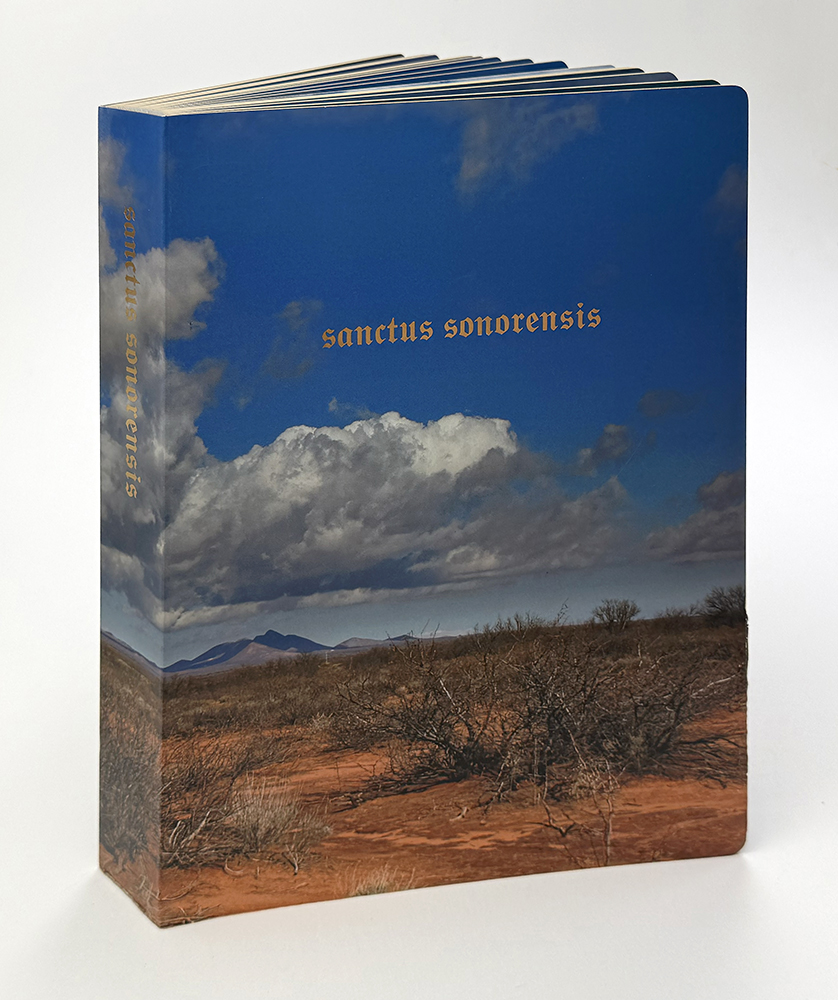

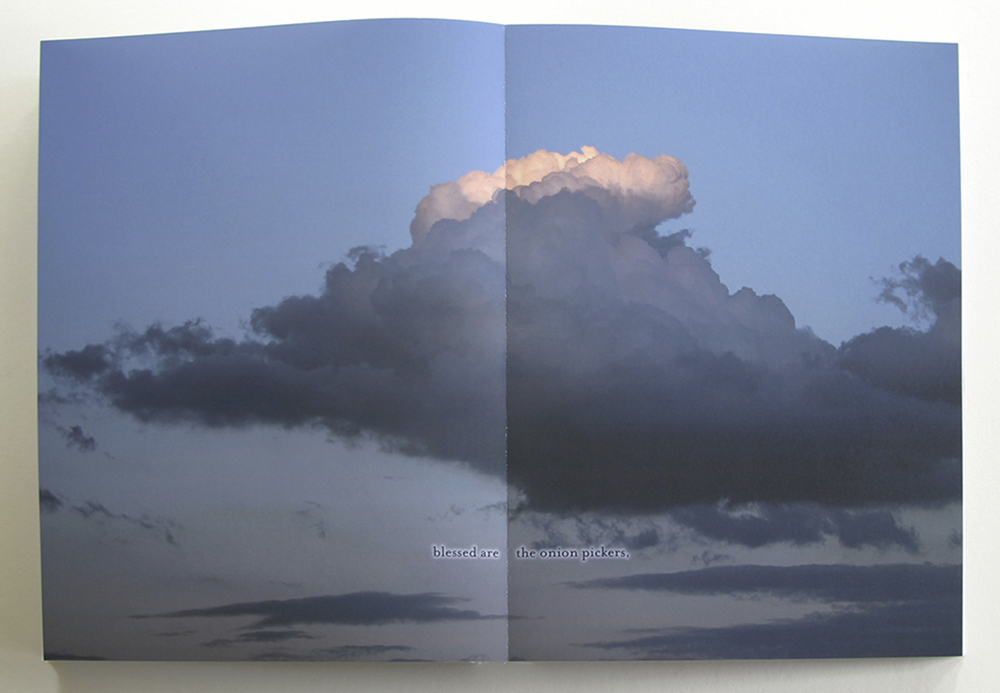

Sanctus Sonorensis (2009)

A board book of Southwestern border ‘beatitudes’. This work comments on the complicated attitudes of Americans on illegal immigration from Mexico. The cover shows an area of Southern Arizona which is the most active in terms of migration across the Sonoran desert, and where thousands have lost their lives in the deadly desert heat. The interior pages show the progression of a typical high-desert day from dawn to sunset, mimicking the sky above an immigrant during a day’s desert passage, and accompanied by a single line of text on each two-page spread. https://spaceheat.com/books/sanctus

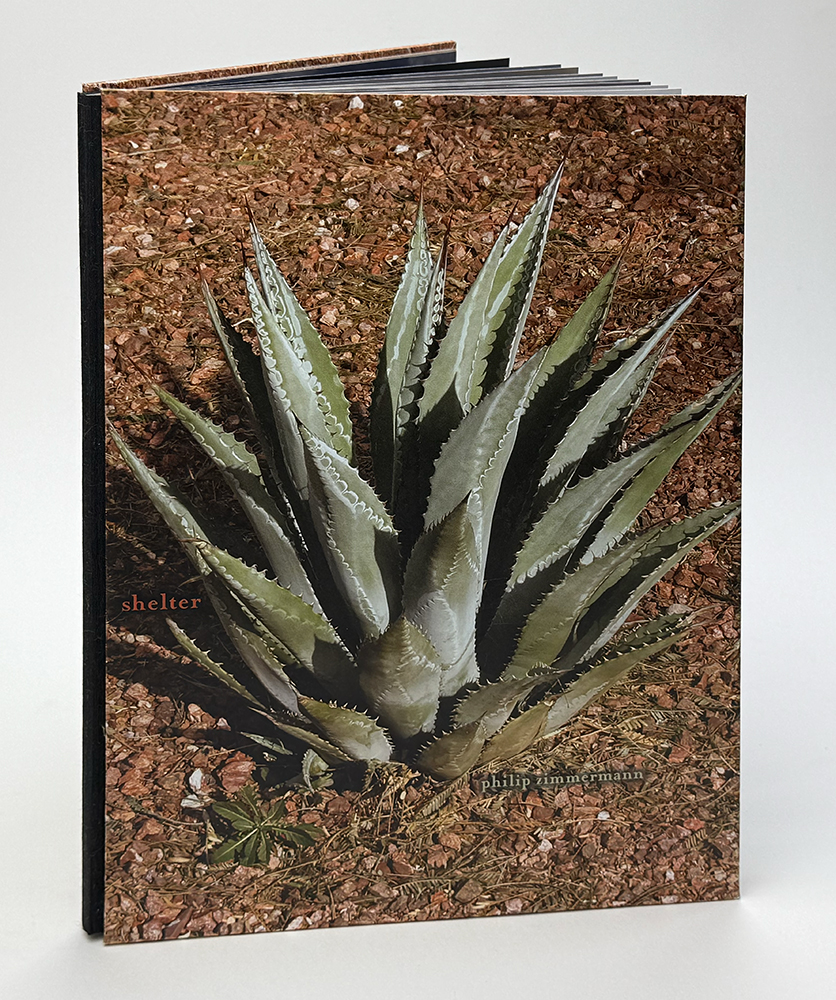

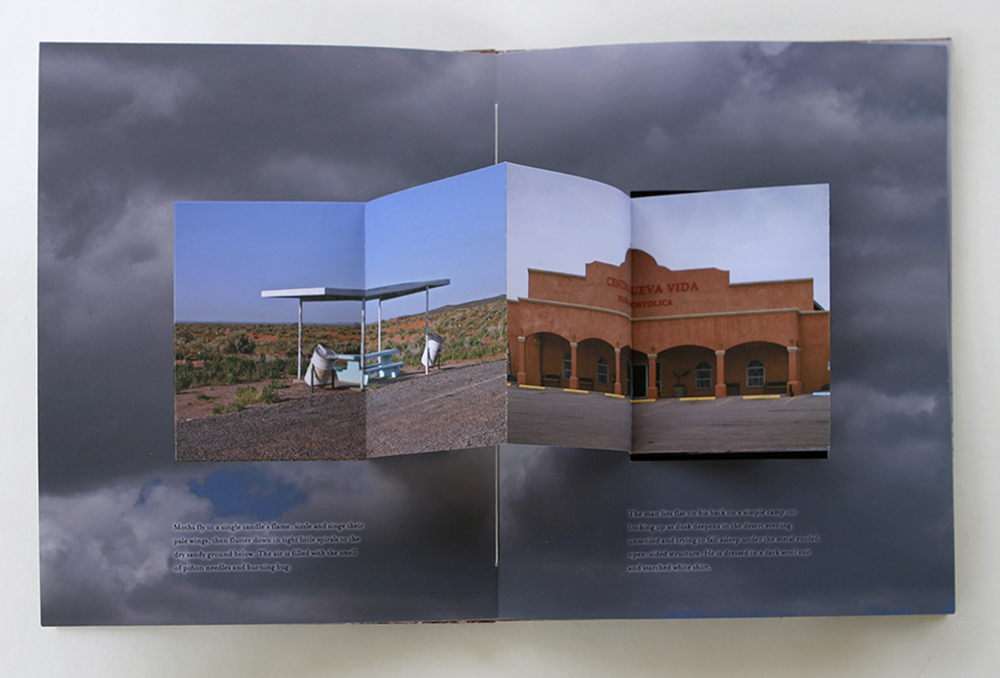

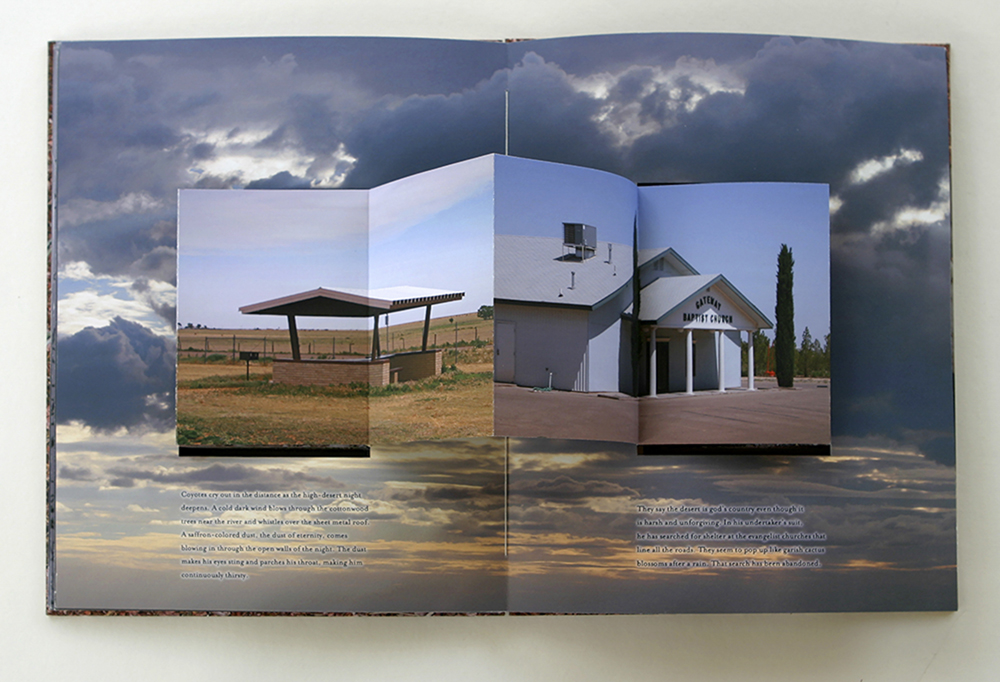

Shelter (2006)

A book within a book. The inner accordion-fold book turns independently as the outer codex pages are turned. The book is about loss of faith and occasionally a desperate rediscovering of it as one reaches the end of life. The structure allows multiple narratives to occur in parallel. There is also text underneath each or the pop-up peaks of the inner book. https://spaceheat.com/books/shelter .

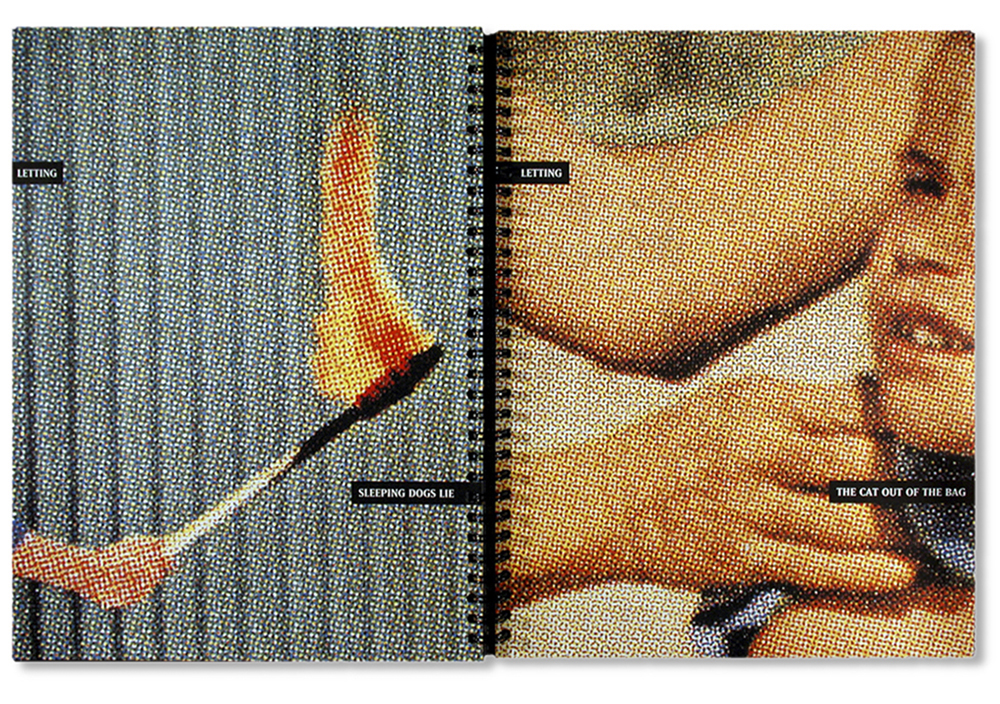

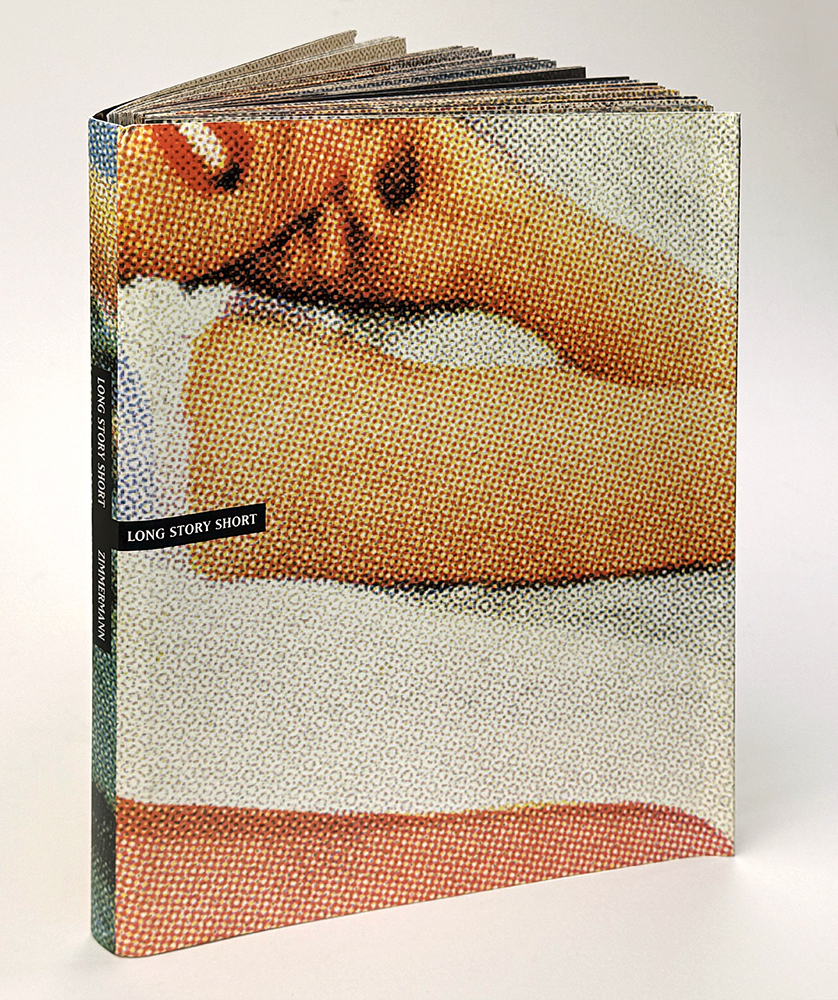

Long Story Short (1999)

A semi-autobiographical book conceived at mid-life. Two devices help tell the story, the first are human hands, perhaps the most evocative part of the human anatomy. The second uses vernacular sayings or truisms to form the narrative. Parts of the text of each aphorism can appear on a next page, sometimes joining or re-forming on later pages. https://spaceheat.com/books/long-story-short .

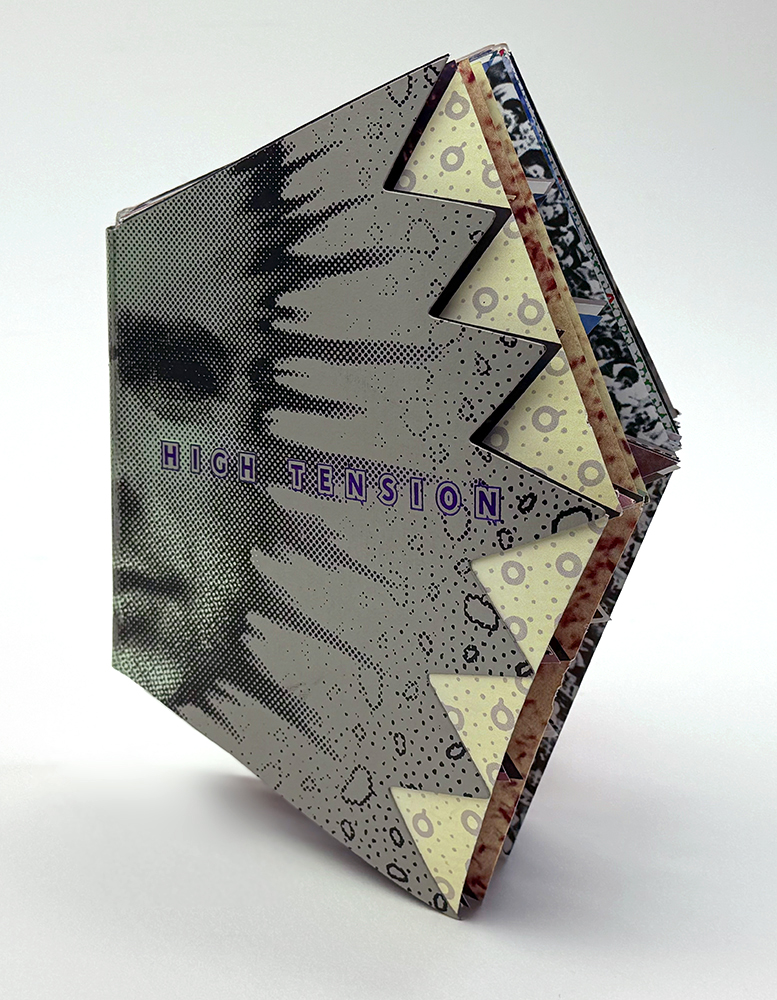

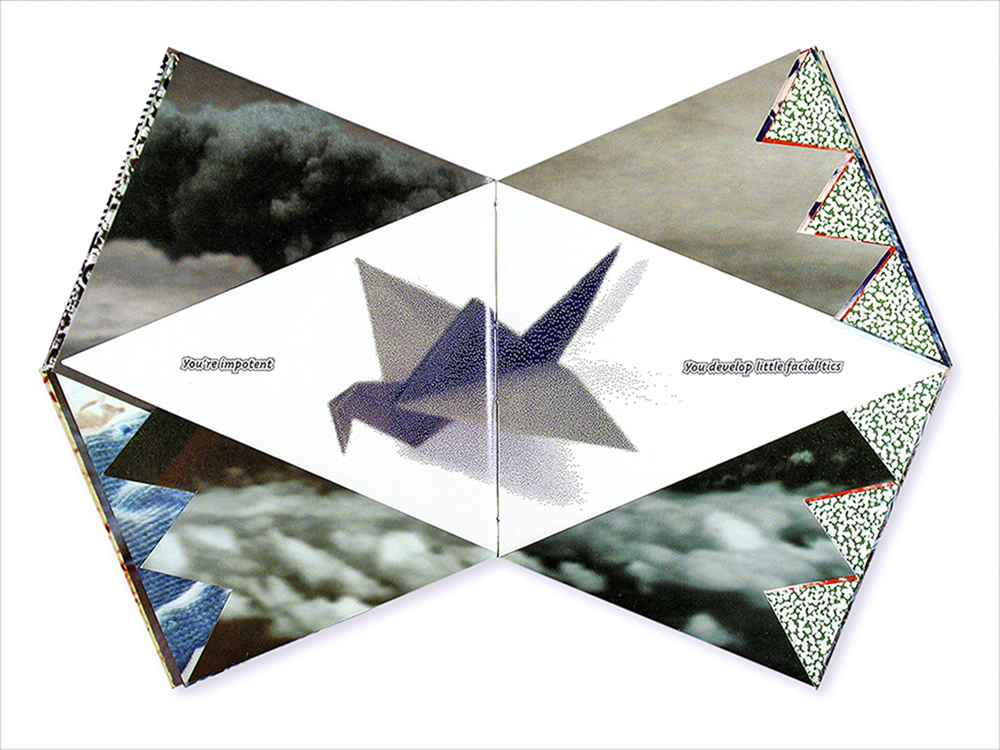

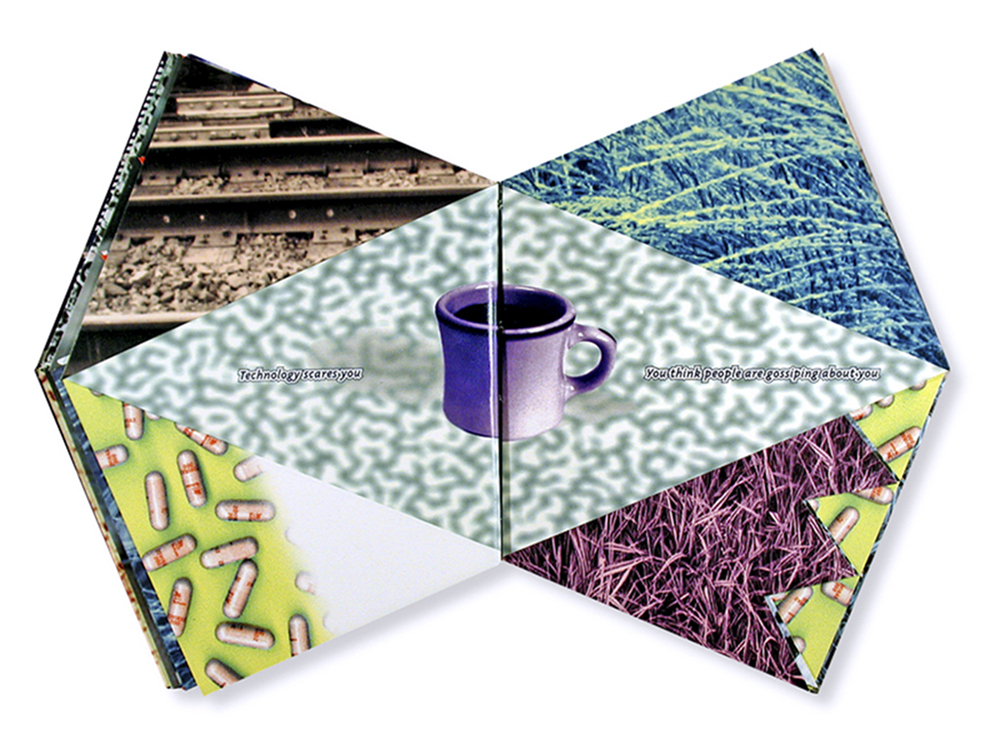

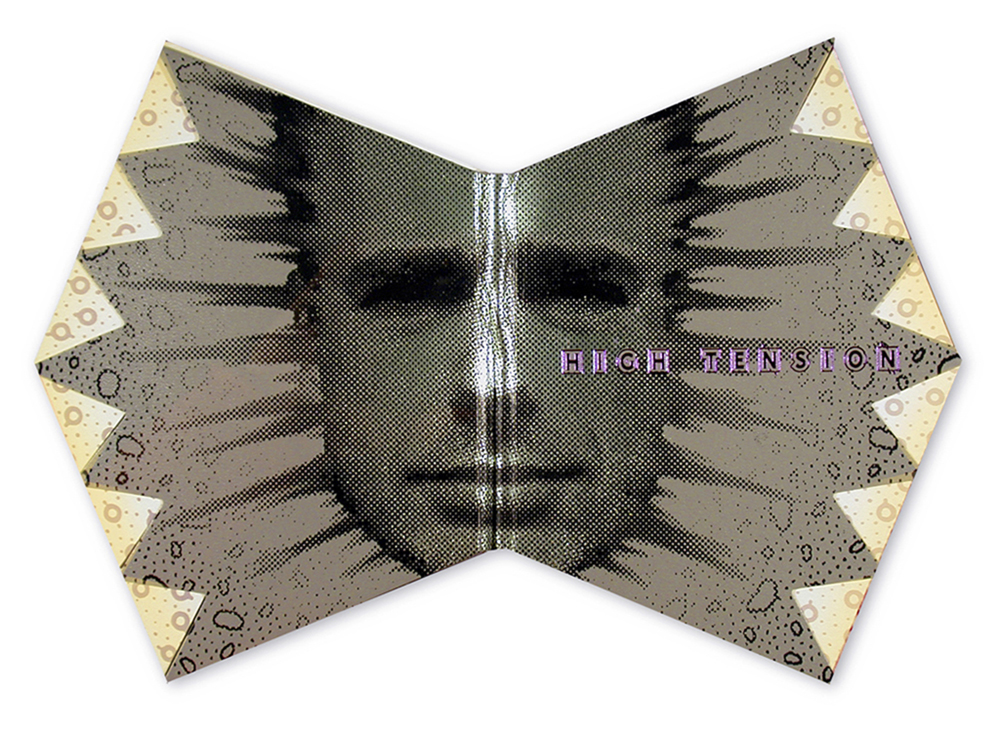

High Tension (1993)

An eccentrically-shaped book that in the first part goes through a clinical reciting of dozens of symptoms of stress in humans. The second part describes slightly tongue-in-cheek solutions to getting rid of stress in one’s life. The book is designed so that on almost every page-spread one can see not just the two standard pages in a spread, but down through three and four page layers below. https://spaceheat.com/books/high-tension

Philip Zimmermann is an artist who works primarily in the form of photo-based artists’ books. His work usually uses a combination of text and photographic images and are generally narrative in nature. They are often about the angst, personal and political, of being alive in today’s culture.

Zimmermann received a BFA from Cornell University in 1973 and an MFA in Photographic Studies from SUNY Buffalo/Visual Studies Workshop in 1980. He taught design and book arts at Purchase College, State University of New York, for 24 years. In 2008 he moved to Tucson and taught at University of Arizona, retiring as Professor Emeritus in 2019. He continues to reside and make work in his studio in Tucson.

Over the last forty-five years, Zimmermann has published over 35 books and received many awards and grants, most under his press name, Spaceheater Editions. In 1994 he received an NEA Regional Fellowship through the Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation, and in 1995 a National Endowment for the Arts Individual Fellowship for Works on Paper/Artists’ Books. He has also received two New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowships, one in 1996 and another in 2005. His work is in many collections internationally, both private and public, including the Getty Research Center, Harvard and Yale University, The New York Public Library Special Collections, The Museum of Modern Art, The Walker Art Center, The Biblioteque National, and The Victoria and Albert Museum, and many others.

Follow Philip Zimmermann:

Website: https://spaceheat.com/

Instagram: @pzimmermann

Email: pzim@spaceheat.com

Books can be purchased directly from Philip (email) or from Vamp&Tramp Booksellers,

[ http://vampandtramp.com/finepress/s/spaceheater-editions.html ].

Many of the books are out of print, but they will be listed at the Vamp&Tramp website as such.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025