Photographers on Photographers: Matthew Ludak in Conversation with Richard Misrach

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Matthew Ludak and Richard Misrach are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

Richard Misrach is an American photographer known for his large-scale prints that capture both human-made and natural changes to the landscape of the American West. His work is instantly recognizable not only for its immersive size but also for its meticulous attention to detail, color, light, and composition. As one of the early advocates for color photography, Misrach played a significant role in redefining what fine art photography could be with the use of Medium and Large Format Color Film.

He is perhaps best known for his seminal and ongoing body of work titled Desert Cantos, which he began in 1979. This series explores the deserts of the American West through images that are at once visually stunning and emotionally unsettling. The photographs in Desert Cantos blend beauty with horror, simplicity with complexity, and aesthetics with politics. Misrach masterfully combines elements of reportage and poetry—whether depicting a brush fire streaking across the desert floor or the hauntingly tranquil images of towns submerged by the flooding of the Salton Sea. His work consistently operates on multiple levels, inviting viewers to contemplate both environmental and social issues through a deeply artistic lens.

Misrach’s other projects have focused on a range of social and environmental issues. Destroy This Memory (2005) documents the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina through raw, text-based photographs that capture the emotional toll of the disaster. In Petrochemical America (1998, 2010–2012), Misrach examines the devastating impact of the petrochemical industry in Louisiana’s so-called “Cancer Alley,” revealing the intersection of environmental degradation and public health. His series On the Beach (2002) and On the Beach 2.0 (2011) was created from his hotel room in Hawaii, where he positioned his camera to photograph people—sometimes solitary, sometimes in groups—set against the vastness of the ocean. These images explore themes of vulnerability, isolation, and humanity’s place within something far greater than itself.

I had the opportunity to sit down for an hour-long Zoom conversation with Richard Misrach, during which we discussed a range of topics spanning his decades-long career. We began with his early work photographing people living on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, California, in the early 1970s, and his conscious decision to move away from portraiture soon after. We also talked about his transition from film to digital photography—and why he has never questioned that decision or looked back. Our conversation touched on his creative process, how he begins a project, and how he knows when it’s time to bring one to a close. Below is a selection of questions and responses from that interview…

Q: So Richard, I’d love to get an understanding of your first exposure to photography. Was photography always a part of your life? Were you one of those kids running around with a camera?

A: When I was growing up, I used to be a serious skier and I was very passionate about it. Every year my whole family would go skiing together. My dad would always put a movie camera in my hand to take the family photos. So I felt comfortable with photography. But that said, in high school, I took a photography class and I think I got a B-minus. I wasn’t very good. Then I went to UC Berkeley for school. I started out as a math major, but ended up in psychology. I wasn’t particularly interested in the arts. In my freshman or sophomore year, I went to this place on the Berkeley campus called the ASUC Studio, (the Associated Students of the University California) at Berkeley. Basically, it was a non-accredited arts studio where they had facilities for lithography, etching, ceramics, and a photography lab. I went there to actually throw ceramic ash trays as presents for my parents for Christmas. But there I saw Roger Minick’s photographs, about 15 small photographs–black and white silver gelatin prints–on the back wall. I was blown out of the water. I had never seen anything like that. That sparked my interest in making photographs and from that moment on I was hooked on the medium.

So I started using this photo lab at the Studio where Roger was the director and had made all his prints. It wasn’t an accredited class—basically it was hobby shop for students and cost $1.50 an hour. But anybody that went and used the darkroom got the same treatment, and I just fell in love with it. I started getting better and better at making images and eventually I got a position on the staff. It was minimum wage, but it allowed me to use the darkroom at night. So Steve Fitch, my co-staff member, and I would start printing when it closed at 11 o’clock at night, and we’d just print all night, because it was free. We could use the the enlargers, trays and chemicals.

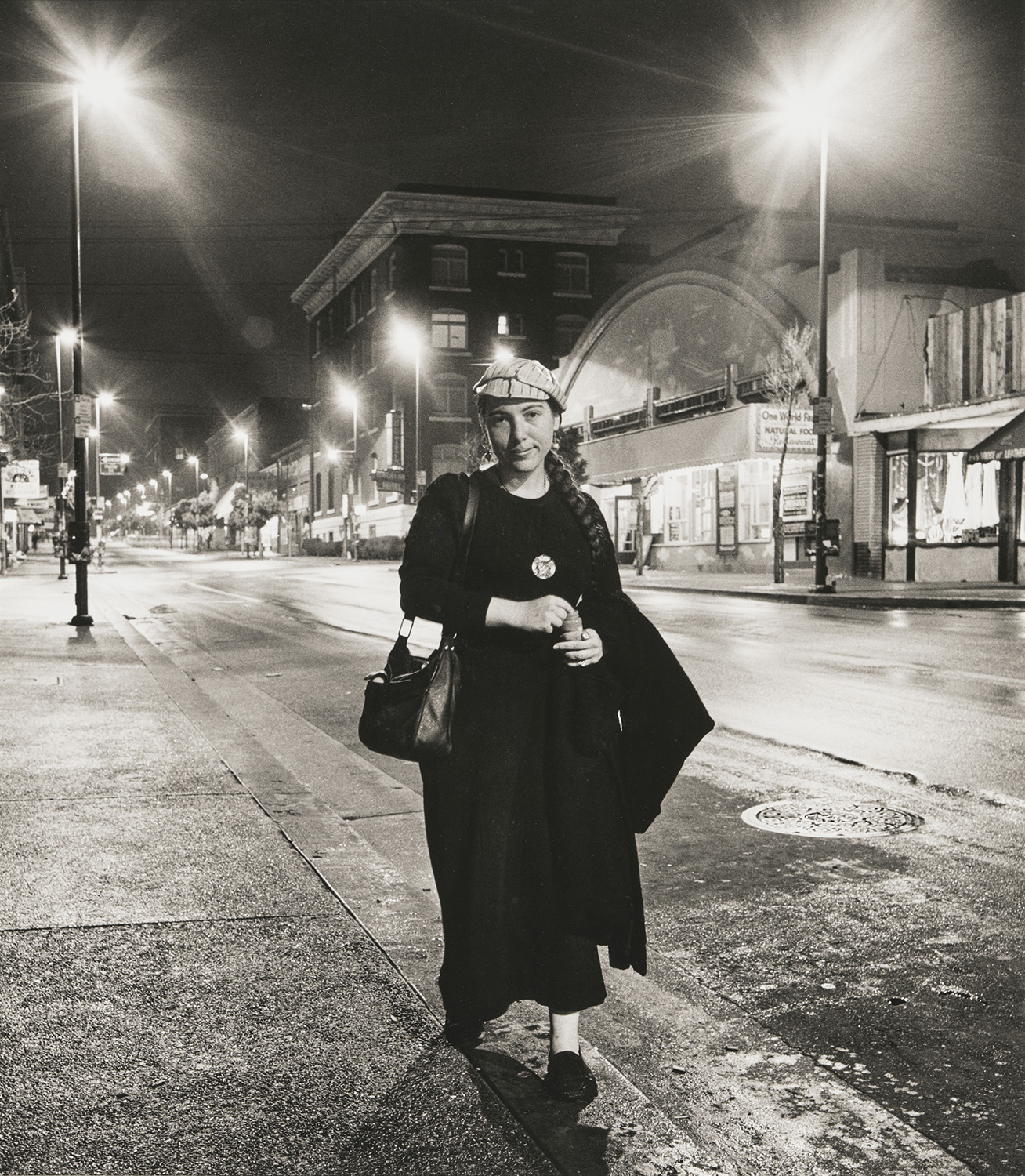

So it was a way to make prints and make work cheaply. People on staff would take turns going on shooting trips. I would get my books and my VW camper and drive to photograph the landscape, then come back after two weeks, run the lab and then the other guys could go off and do it. It was kind of my photography apprenticeship. While I was there, Roger guided me along. He helped me in developing my first book, Telegraph at 3 a.m (1972-74). In 1971, I got my degree in psychology. I was supposed to go to graduate school in psychology, but that never happened.

You couldn’t make a living as a photographer back then. I remember Ansel Adams invited Roger Minick to his house and studio and Roger brought me along. We got to go see him, and he was making coffee can labels with his images in order to make a living. Just to give some perspective at that time nobody made a living with photography. But I just made a decision that I was going to pursue photography for a year…… and that was that, I never looked back.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about your early work with portraiture? I find your Telegraph at 3 A.M. series really interesting because it is just so unlike much of your other later work. How was your experience with that sort of a more “traditional” documentary or photojournalist approach and also just your experience photographing people?

A: That’s a good question. It’s pretty complicated, but the short version is, I did the portraits, the street portraits, and these portraits at least at the beginning were very challenging for me to do. I actually had nightmares of people looming over me, and in my “vision”, that’s how I got over my fear, by going out and making these portraits. So when I first went to photograph on Telegraph Avenue, I was afraid. But when I started photographing the people living out on the street, I decided to bring prints back to give them so they could see what I was doing. The people I was photographing loved them, and they just welcomed me. Soon they were inviting me to photograph them shooting up heroin and all kinds of really crazy stuff. So I went from being an outsider and feeling really uncomfortable to being part of the scene and feeling very comfortable. I spent a couple of years doing that. But after it was done, and I thought I was doing something good by showing what people were going through, living on the street and all, and raising money with the work for the Free Clinic. But I received really bad reviews and was accused of basically exploiting these people, my peers. I think it was like a wake up call. Again, I was in my early 20s. I was young. So I think in that moment which felt really brutal, I kind of said, “I don’t want to photograph people. I think I want to get away from that”. So I really shifted gears. And before you knew it, I was reading Carlos Castaneda, and other spiritual literature and I was was off into the desert photographing Cacti at night with a strobe. I completely and radically changed my approach to what I was interested in photographing. I would say I felt uncomfortable, photographing people after some of the reactions I received from not necessarily the people I was photographing but the outside art world. I had shows at the ICP of this work, when I was 25 years old. My career taking off, gaining lots of attention for that, some good, some bad. Yet I was making these pictures but it wasn’t helping these people. I realized I was exploiting people without intending to. So that was the first reaction. Now, 50 years later, I’m very proud of that work. Looking back, I feel that it’s a really important historical document. It shows what photography can do, shows what things were like at that moment. At that point, I turned away from photographing people and started photographing landscapes as people, which opened up another language for me.

Q: I’m curious about how you typically begin a new body of work. Are you a meticulous planner who needs a clear roadmap? Or do you start with a general idea or interest in a particular place and allow the work to evolve more organically? You mentioned the advice Roger Minick gave you—not to go out and shoot blindly, but to have some kind of plan or purpose—and I’d love to hear how that has shaped your approach.

A: I learned a long time ago if I head into the desert with a particular idea in mind, it never amounts to much. So I came up with this notion that has worked beautifully ever since: being “aggressively receptive.” Basically I head out onto the road with no specific plans and just remain on hyper alert, and inevitably I discover something truly remarkable beyond anything I could have imagined.

Q: Can we talk a little bit about collaboration? Because you have mentioned before that you enjoy the process of spending time on your own, sometimes for weeks at a time often in very remote or isolating settings and locations working on a project. I just wonder how then you arrived at collaborating with other artist and I’m primarily thinking of your two books Petrochemical America and Border Cantos.

A: Over the years I’ve had three major collaborations that I’ve done, and I have found them extremely valuable. The first collaboration, actually, was with my wife, Myriam. When we first met she was a writer for Mother Jones Magazine, and she wanted to do a piece about the series I was doing on the Bravo 20 bombing range in Nevada. Also, I worked with Rico Salinas, who’s an artist in this co-op building where I am right now. He’s a painter and he did the illustrations. I found an architectural firm in Los Angeles that did these architectural models of the Bravo 20 bombing range for the book. So that was the first collaboration. Secondly, I found Kate Orff to collaborate with me on Petrochemical America and then Guillermo Galindo on the Border Cantos. Every time one collaborates like that, you end up creating something much bigger and different than you would just by yourself. I found that so rich and so powerful. I wouldn’t want to do that all the time. I love doing most of my work solo. But by collaborating once in a while, it expands your language, if you will, in great ways. So I actually think it’s a really interesting model to incorporate. And it’s got to feel natural, so I’ve been very lucky.

Q: You’ve mentioned briefly your transition from film to digital. I’d love to hear a little more about this. Was this a difficult transition for you to make? What it a gradual change in your professional practice or did it happen almost all at once?

A: When I started shooting digital, I shot 8 x10” color film. Then I began transitioning over to digital in 2005, its funny, somebody accused me of going to the dark side. I swear to God. It then became kind of a joke, but I was so relieved to work that way. I realized how obsolete and outdated this whole process of loading film in the back of my van, taking an hour to load it, unload it, going back to the Motel 6, so I could sit on the bathroom floor at night and have a place where I could change film. And then, the development of color film and the costs, every time I took a picture it would be 20 bucks. But when I began to start shooting large format digital the first year (2005) the quality wasn’t quite there. So I said, “No, not there, not for me.” The second year though, when I was able to use a medium format digital Hasselblad, the quality was so much better. I saved a fortune. I used the same little digital card for thousands of pictures. It’s crazy just how much money it saved, not to mention all the time it saved. But for me, it was liberating to just be able to shoot so much more. I could photograph things that I could not shoot with an 8×10. Like photographing people swimming or surfing in the ocean from my hotel room in Hawaii. That whole project (starting around 2006—On The Beach 2.0) wouldn’t have been possible with my 8×10. By the time I’d even get the thing focused and get the film holder in there, the people would swim off. But with my digital camera, my Hasselblad and a Phase One digital back, oh my God, I could just capture things when I saw them. I photographed baptisms. I photographed amazing things. There’s no way I could have caught that with the 8×10. No regrets there.

Matthew Ludak is a documentary photographer whose work delves into contemporary social issues, including classism, de-industrialization, environmentalism, and structural racism in the United States.

Ludak’s approach employs natural light and classical composition to highlight the dichotomy in how artists are able to depict difficult and troubling topics. His work has been exhibited and published both domestically and internationally, showcasing his talent at venues such as The Elliot Gallery in Amsterdam, Prix Maison Blanche 2024, Photo Marseille, the Head On Photo Festival in Sydney, Australia, and the Photography and Visual Arts Festival in Braga, Portugal.

His long-term project, “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” has garnered funding from the Puffin Foundation and was selected for the 2024 Critical Mass Top 50 by Photo Lucida.

Instagram: @ludakieiwcz

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

![328-02 [Half-Beach, Half Water], 2002](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/328-02-Half-Beach-Half-Water-2002.jpg)