100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians Project

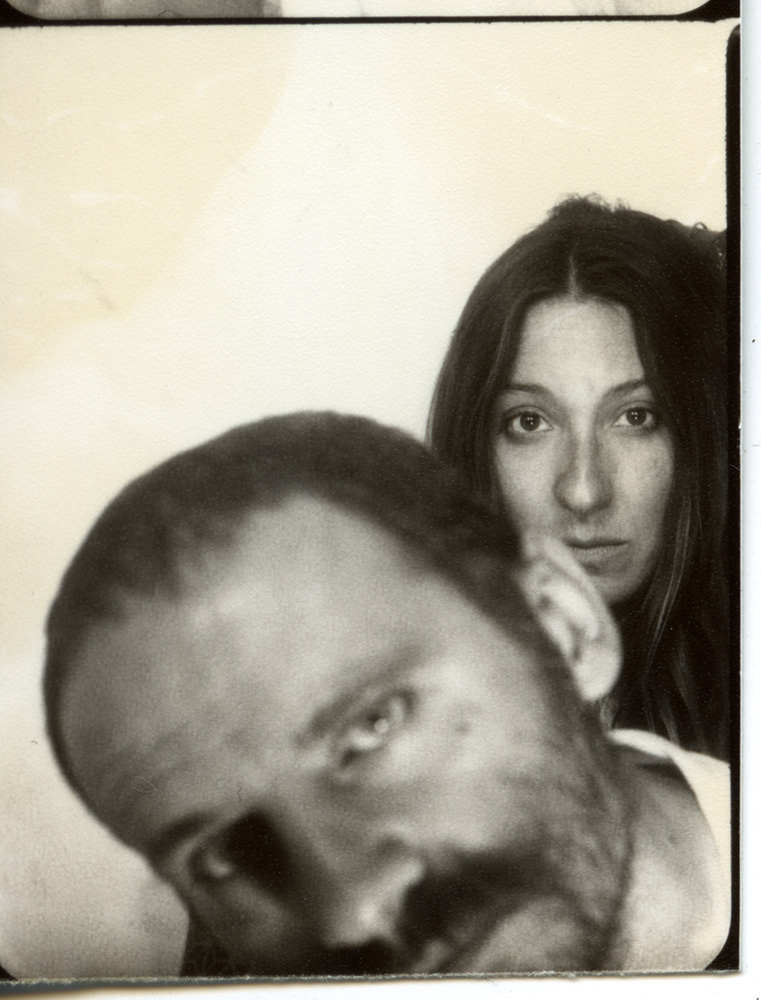

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project, © Photography by Angela Yu-Hsin Chen: @binbimchen

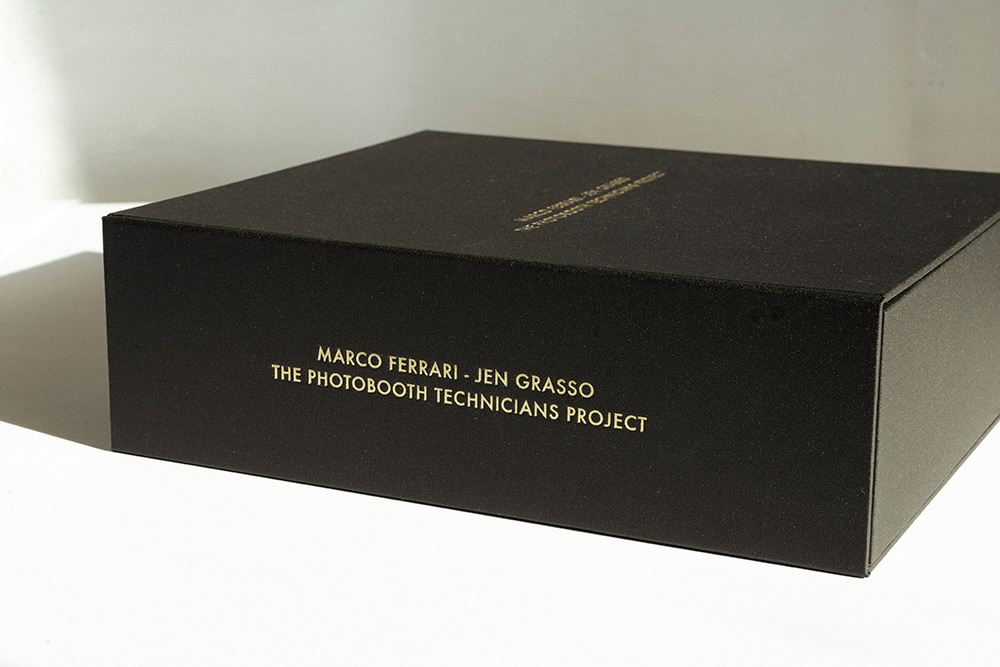

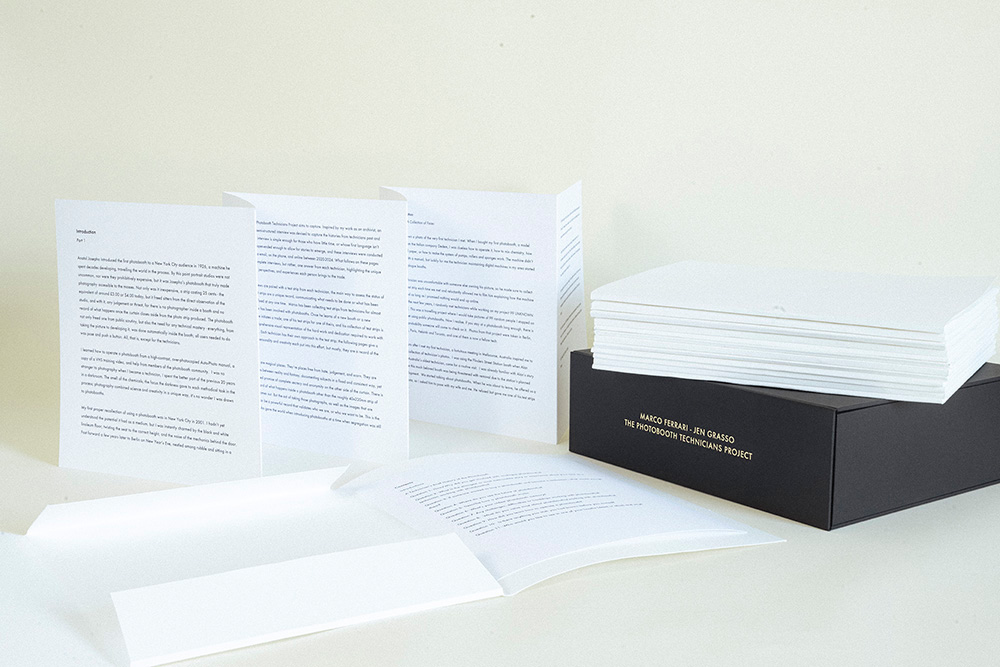

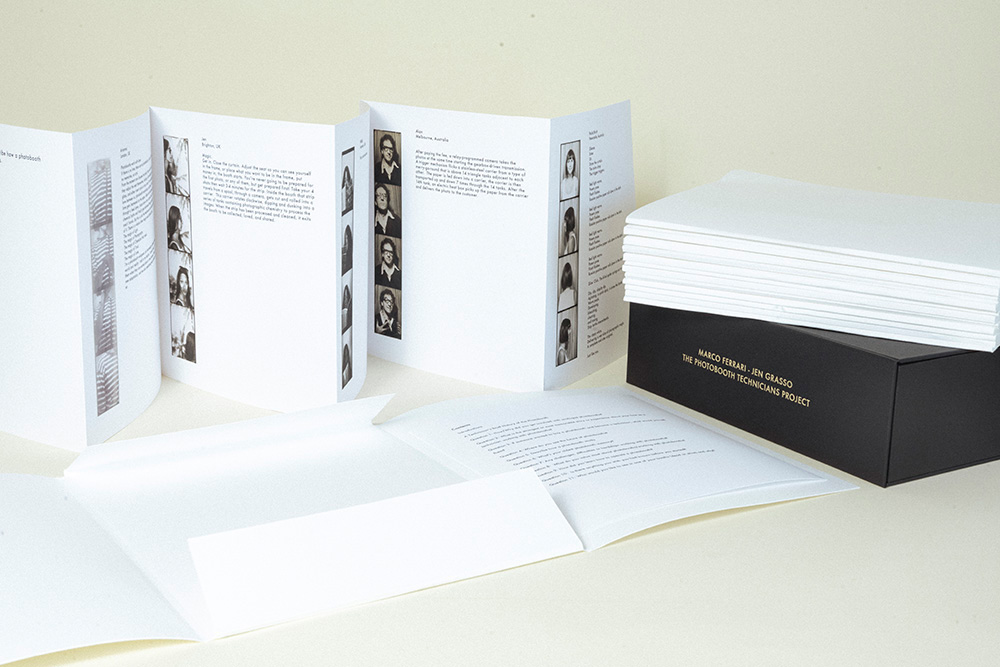

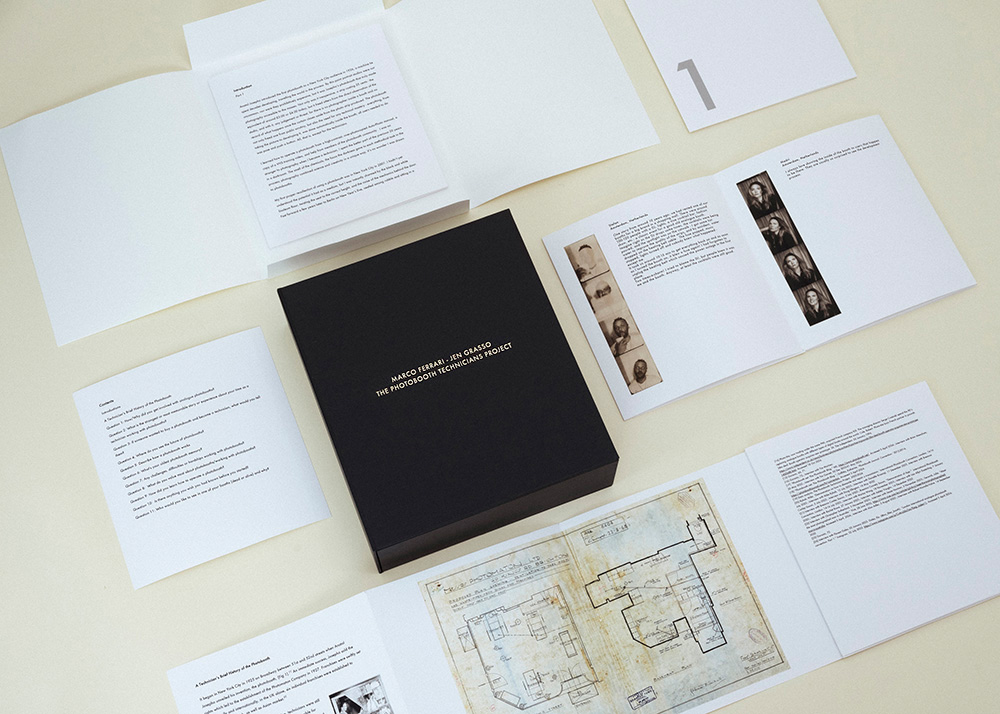

Many of us do not realize that behind the scenes of the vintage analog Photobooth rebirth are dedicated and knowledgeable photobooth technicians. The Photobooth technicians service, adjust, maintain, repair and troubleshoot the booths. They mix and refresh the chemicals for the miniature dip-and-dunk darkroom inside the booth, change the paper and perform other maintenance to ensure that the booth works magically for anyone stepping inside to take a photo. Technicians may also need to repair or change a part of these vintage machines. Often when something breaks, they might have to fabricate a part or reach out to a community of other photobooth technicians spanning the globe. I met Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari at Photo London 2024 and learned that they both are Photobooth operators and technicians. They were working on a book, The Photobooth Technicians Project which was released during the 100th anniversary celebrating the Photobooth in 2025. The presentation of this remarkable project representing five years of research and interviews with technicians is an exquisitely-crafted artist’s book. It is a community archive project as well as a wealth of analog Photobooth information and history.

I became fascinated with the community of Photobooth technicians that make it possible for these vintage machines to continue to function and exist, so that 100 years after Anatol Josepho’s invention, we are still able to pull aside the curtain, sit inside, take a photograph, and walk away in minutes holding a unique object and artifact. It’s magic.

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project, © Photography by Angela Yu-Hsin Chen: @binbimchen

Jen Grasso is a photobooth technician and archivist at the University of Brighton Design Archives in the UK. As an archivist her work focuses on the dissemination of Design Archives collections in addition to managing the archive’s digital preservation. Her research interests lie in the intersection between analogue and digital technologies, and the use of technology to democratise culture and heritage. She has also worked as both an analogue and digital photobooth technician since 2015, and has worked over two decades as a creative practitioner with analogue photography, in particular instant photography. Alongside Marco Ferrari, she is the co-creator of the analogue photobooth community archive and the Photobooth Technicians Project.

Jen Grasso: IG @brightonphotobooth

Marco Ferrari is a photographer, artist and technician whose work centres around photobooth portraits of different people and different communities, which he’s travelled around the world to capture in booths. Featured in both solo and group exhibitions as well as a regular series in The Developer Magazine in the UK, Ferrari’s work pushes the boundaries of traditional photobooth photography. Alongside Jennifer Grasso, he is the co-creator of the analogue photobooth community archive and the Photobooth Technicians Project.

Marco Ferrari: IG @pplinphotobooth

For more information on the book, please email photoboothtechniciansproject@gmail.com

The Project: IG @photoboothtechnicians Additional views of the book and a video can be seen on IG

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project, © Photography by Angela Yu-Hsin Chen: @binbimchen

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project, © Photography by Angela Yu-Hsin Chen: @binbimchen

J.K. Lavin: What is your photographic background preceding the photo booth? (Jen and Marco) How did you two meet and is it related to photobooths?

Jen Grasso: My photographic journey started when I was first introduced to photography and darkroom printing as a teenager, and from then on I spent as much time in the darkroom as possible. I went on to study photography at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. After graduating I exhibited in international group shows, travelled, and eventually moved to Berlin where I lived for almost a decade. As many know, Berlin has the largest concentration of booths in the world and I lived within a couple of blocks from a photobooth throughout my time there. Given my love of instant photography, they were used a lot. In Berlin I also did a practice-based postgraduate degree but not too long after completing that I moved to Brighton, England and traded in my camera for a photobooth.

Marco and I first met when he asked for my test strip for his collection. We chatted on and off and slowly built up a friendship. He was my first interviewee for the Tech Project and this was during lockdown before we joined forces and rolled it out to the wider community.

Marco Ferrari: The search for analogue photobooths at a time when almost all of them were already gone in Italy actually sparked my photographic journey. I started using Polaroid Miniportrait cameras with original Polaroid film as a way to take portraits of people on the go. These cameras made for ID photography opened a world to me, I started shooting with any Polaroid camera I could find. From the classic SX-70 and 600 to peel apart film like the Polaroid 195 and the CU macro camera made for dental photos. I then moved to 35mm, medium and large format to cameraless techniques. What is striking to me is that the photography part is actually the easiest to learn when dealing with photobooths. Someone starting with these machines is actually way better off if they know about mechanics or electricity.

I used Jen’s booth a couple of times before even meeting her. At one point Brighton had two analogue photobooths but I always sent people to hers because it always had better quality and I thought she was much much cooler. After getting to know her I can confirm she is.

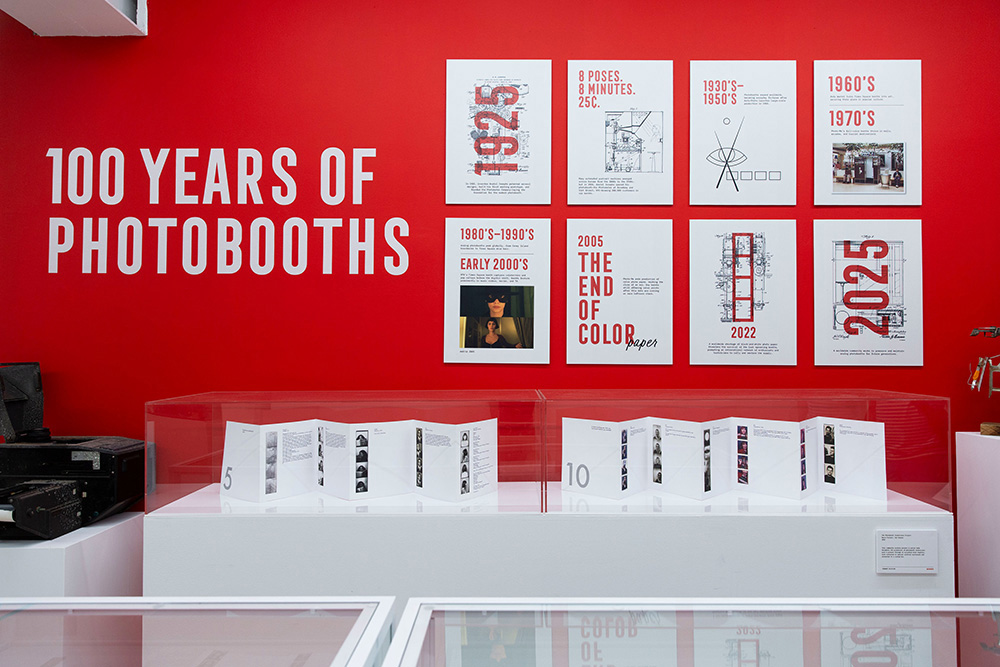

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari,The Photobooth Technicians Project on display at the Photobooth Museum, NYC. Photography © Ali Clark @heyaliclark

For those not familiar with what’s involved in being a photo booth technician, what happens on a typical day?

(Jen) That depends on a number of factors, but a typical ‘top up’ visit would entail visiting the booth, checking the counter and writing down the number of times the booth was used and this information is checked against income to confirm the number of strips taken which can also help identify issues if the numbers don’t match up. I would then look for any lost strips, top the tanks up with water, as the inside of the booth contains tanks of photographic chemistry and water which evaporates over time, low levels mean pictures won’t get developed. I’d clean up any spills, deal with any issues, replace any parts or put a new roll of paper in if needed, clean the inside and outside of the booth before checking with the staff at the store where it was located to make sure everything was ok. I would do this twice a week, and full chemistry changes would happen every 6-10 weeks. That involves much more work.

(Marco) What also makes a great difference is where the machine is located. Quite a few photobooths in Europe are on the street or in open locations with little surveillance so sometimes you end up spending most of your time cleaning them, from anything from graffiti to human waste.

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project on display at the Photobooth Museum, NYC. Photography © Ali Clark @heyaliclark

What are the greatest challenges operating an analog vintage photobooth?

(Jen) Not having help. Following that, not having access to parts that are no longer made, as well as other supply-line issues. Analogue booths today might run on the same technology that was invented in the late 1940s, but each booth is different, each one has its own quirks and some issues aren’t in manuals. It helps to have someone to bounce ideas off of, to get another perspective to help figure out what you’re missing. I was a sole owner so I didn’t have anyone to ask. And because I operated alone, it was hard for me to get replacement parts or chemistry because I wasn’t buying in large amounts, especially post-covid when the landscape changed drastically.

(Marco) You are always chasing a problem and as soon as you solve it another one comes up. I believe now the number of issues a machine has is somehow connected to how cheap it is. The more expensive a photobooth is, the less is used while still keeping revenue. The cheaper it is and more people can enjoy it but heavy use will lead to more frequent issues.

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari,The Photobooth Technicians Project on display at the Photobooth Museum, NYC. Photography © Ali Clark @heyaliclark

What is the most unusual use of the photobooth that you’ve seen or heard about?

(Jen) I’ve seen people use booths as changing rooms, toilets, hotel beds/rooms, in scavenger hunts, and overall location identifiers (meet me by the booth), but this is expected for outdoor booths, though I’ve seen most of that with indoor booths too. Creatively? I haven’t found a strange strip yet. I love seeing the ways people push the limits of the medium. I, alongside some other artists and techs have experimented with making zoetropes, which I plan on continuing, and many experiment with mirrors, backgrounds and other props to create dazzling effects.

(Marco) While I was servicing a booth in a busy food court in central London I went to get some water while leaving my tools inside the machine. I came back and to my surprise a mum was having her toddler using a portable potty in the booth with the curtain drawn. All of this in a place with accessible toilets.

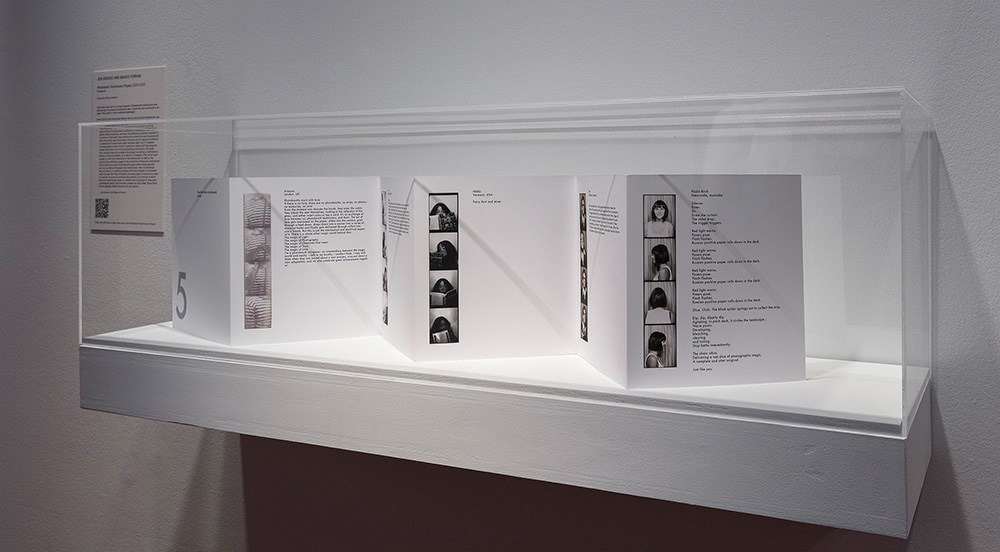

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project on display at RMIT Galleries / CCP Melbourne’s ‘Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits’, photography © Christian Capurro

Tell us about the project and its final presentation. What was the objective or premise? How many technicians from how many countries did you interview and how did you find them? How long did the project take and is it ongoing?

(Jen) I am an archivist and was working on cataloguing an oral history collection that ranged in topic from childbirth during the second world war to the success of taking industrial action, racism and immigration, to social housing. These interviews were powerful, and inspired me to think about my fellow photobooth technicians, owners and operators. We are a grassroots group who got into the industry through different routes, each learning the trade differently, each bringing something different to the profession. I wanted to learn more about this grassroots community that I was part of, I wanted to connect with everyone because we are distributed around the world.

I developed an interview and Marco was my first interviewee, but it wasn’t until some time later when I realised that Marco’s collection of test strips was the perfect complement to, and visual representation of, the community and the people I wanted to interview, so that’s when we rolled it out as a joint project.

The objective from the start was to document the profession of analogue photobooth technician. There are records about the companies, for example articles of incorporation, investments, and so on, but there are no records, or if there are, they are obscured behind corporate lines, about the people who have dedicated their lives to keeping analogue photobooths running day in and day out, past and present. How did they get involved in the profession, who taught them, what can they tell us about photobooths and their experience of working with photobooths? This is what we want to document, the stories and recollections from the people who have worked and continue to work with these machines.

As of writing, we have 50 technicians from 11 countries, and are hoping to get a few more interviews under our belts soon! I started the Project in 2020 but together Marco and I rolled it out in 2022 to the community, and yes, it is still ongoing!

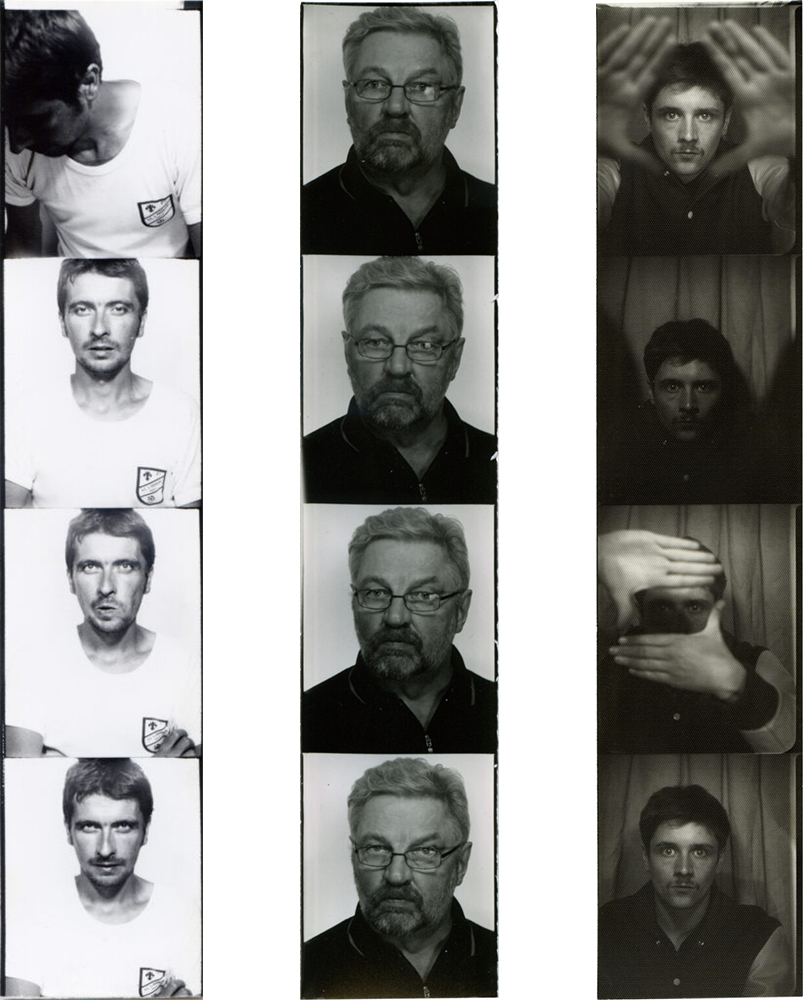

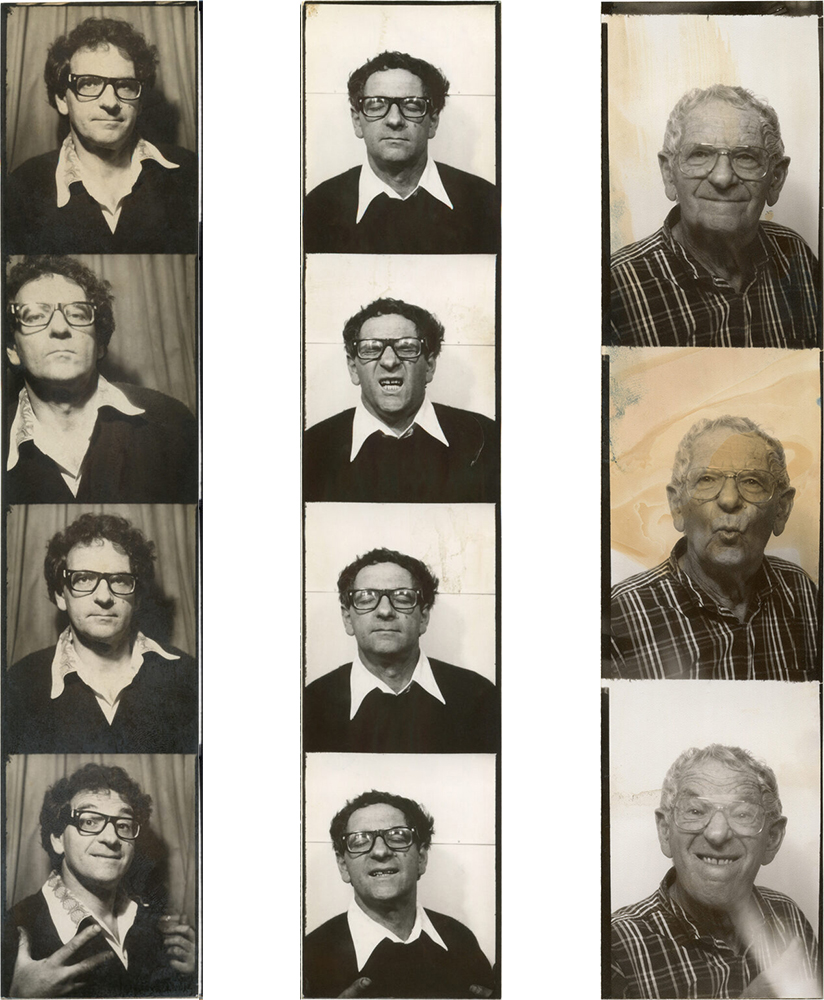

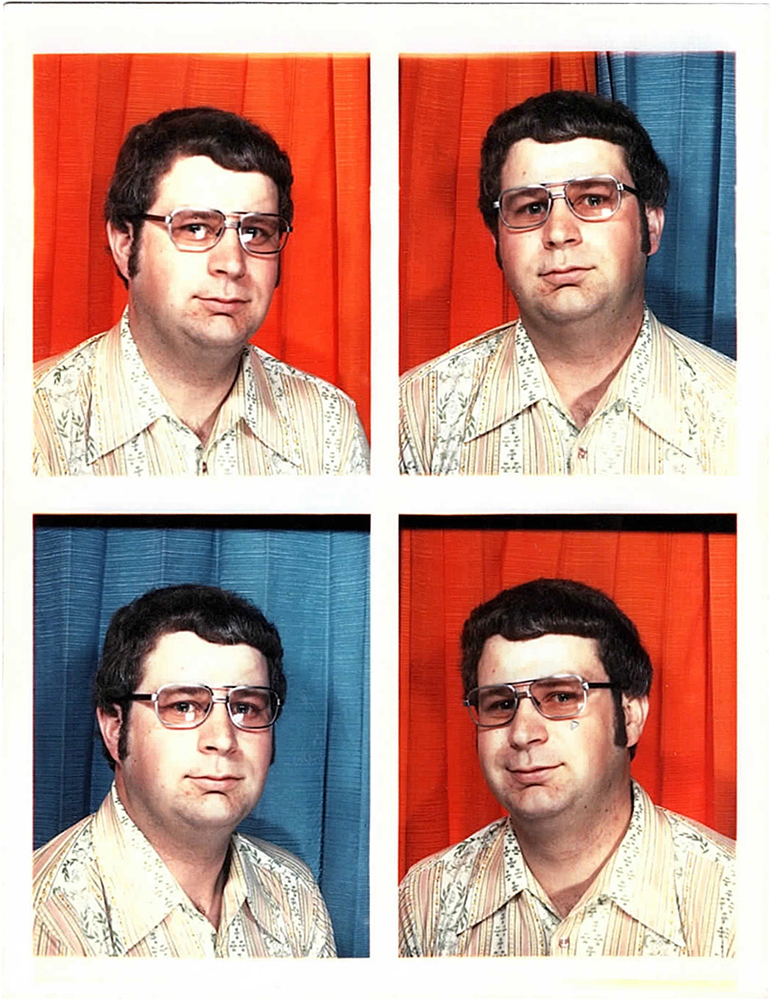

(Marco) My input to the project was initially the collection of test strips I got from Technicians all over the world. From 2009-2012 my project, “99 Unknown People” took me to Berlin, Paris, Helsinki, Cesena and Toronto. I was spending so much time next to the booths so that I could get 99 people to pose for a strip that always ended up with a photo from a tech visiting the booths. It was, however, in 2019 that I had the idea of a photo swap. We were in Melbourne using the famous Flinders Street Station photobooth and after a while Alan Adler, the oldest and probably most famous Technicians in the world, came to work on the machine. After a lengthy chat I asked him to pose for a strip with my wife and I. He kindly refused but he reached into a bucket and pulled out one of his test strips. That strip sparked the idea for my collection.

Jen Grasso and Marco Ferrari, The Photobooth Technicians Project on display at RMIT Galleries / CCP Melbourne’s ‘Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits’, photography © Christian Capurro

One of the questions from the project, number 11: Who would you like to see in one of your booths (dead or alive) and why? What were your answers to this question? (Jen and Marco)

(Jen) Patti Smith. I’m a huge fan but I also know she has an appreciation for analogue photography and if anyone would appreciate the magic of the booth it would be her. I’d also like to see Talbot, Daguerre and Julia Margaret Cameron in the booth (not necessarily together). As the inventors of photography, and Margaret Cameron can be argued having taken one of the first selfies, it would be interesting to see what they think of this type of photographic invention.

(Marco) I already had the luck to have my favourite director, Ken Loach, to pose for a strip for me after an event in London in a cinema where there was a photobooth.

My answer to question 11 of our project was Paul McCartney. I’m obviously a huge Beatles fan but I am also curious to see how someone who has been in the spotlight for his entire life would act in the photobooth, an enclosed space, quite private with the curtain drawn, without a photographer in front of them.

Please share some of the most unexpected things you found or learned compiling this project.

(Jen) The most interesting would be the recollections from the technicians who worked for Photo-Me and Auto-Photo when they were still active with analogue booths in the UK and US, respectively. Hearing how these companies operated – the line management, how organised it was, how easy it was to get a spare part, supplies, training, but also how taxing it was because it is hard work, and the company was in charge of the route or region one covered so they controlled the number of machines one serviced, not the tech. Some experiences are very similar to working with photobooths today, some are very different, it’s interesting to have this variety of perspectives.

(Marco) I guess the biggest difference from Photo-me/Auto-Photo technicians and newer independent ones is how they got to the job. Nowadays, if you can find a photobooth to buy, you come to it because you love the medium when before it was, for most of them, a job like any other. That’s why in Europe everyone was happy to switch to digital ID photobooths because it became a cleaner, easier and faster job.

Do all technicians collect test strips and left behinds?

(Jen) No, not all. I used to leave them in the frame on the front of the booth for their creators to reclaim them, which others do too.

(Marco) No, some technicians keep all their tests, some keep just the best and some don’t keep any. I started collecting left-behinds before I started working as a photobooth technician. I actually keep any photo found on the street. Over the years I collected analogue and digital photos but also magnets, collages etc.

Where has the “Photobooth Technicians Project” book been exhibited? Is there an edition and is it available?

(Jen) Yes, it is a limited edition custom-made concertina art book, and it is available to exhibit and purchase. The first version is currently on display and part of the permanent collection at Autophoto’s Photobooth Museum in New York City. Chapter 5, which featured Australia’s oldest technician, Alan Adler, was exhibited at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in conjunction with the Centre for Contemporary Photography’s exhibition, ‘Auto-Photo: A Life in Portraits’, that was about Adler. I’ve also been fortunate enough to have shared the project at several conferences and symposia. We would like to continue to exhibit the book, as well as find other ways to share the output from the project, whether as an exhibition, publication, or something else entirely.

What are your plans for the original source material of the archive?

(Jen) To deposit it somewhere so it’s accessible to all. At the moment, it’s just one part of a community archive but I’d also like to expand this archive and feature more voices in the community. Who knows if that will take off and where that will lead, but I will catalogue all the material and make it available for anyone who is interested, and hopefully deposit it in a permanent location one day.

What’s next for you with the project?

We’re still interviewing technicians, we’re still exploring publication routes, there is so much more to say and share than has been, this is just the start.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025