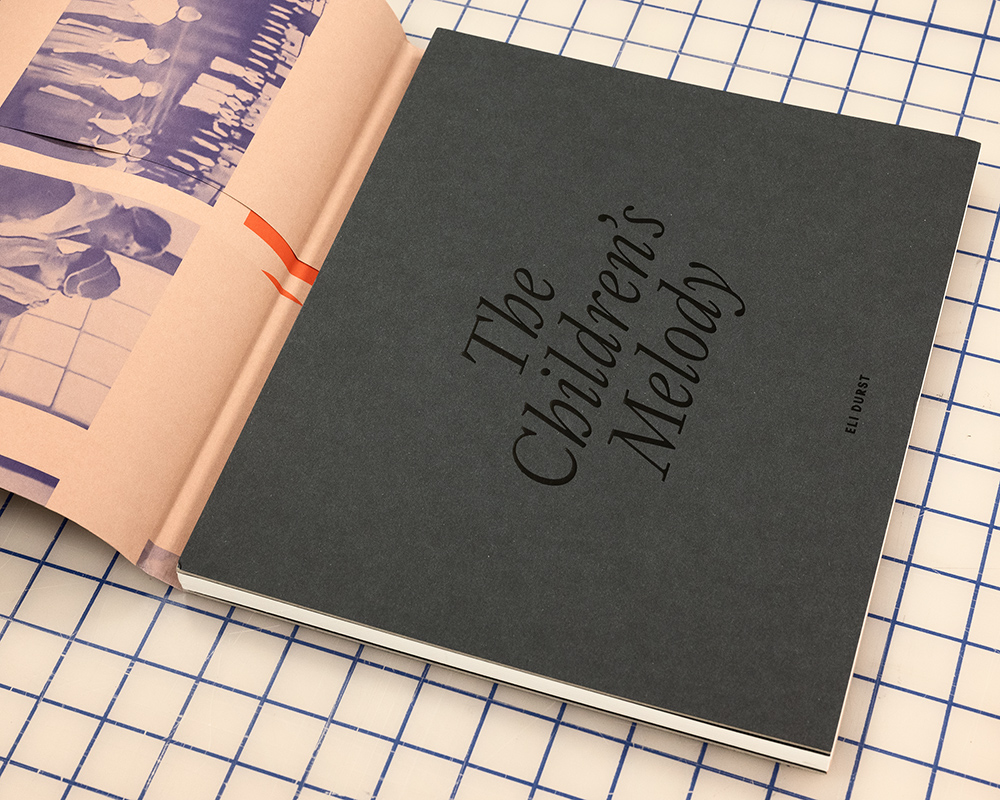

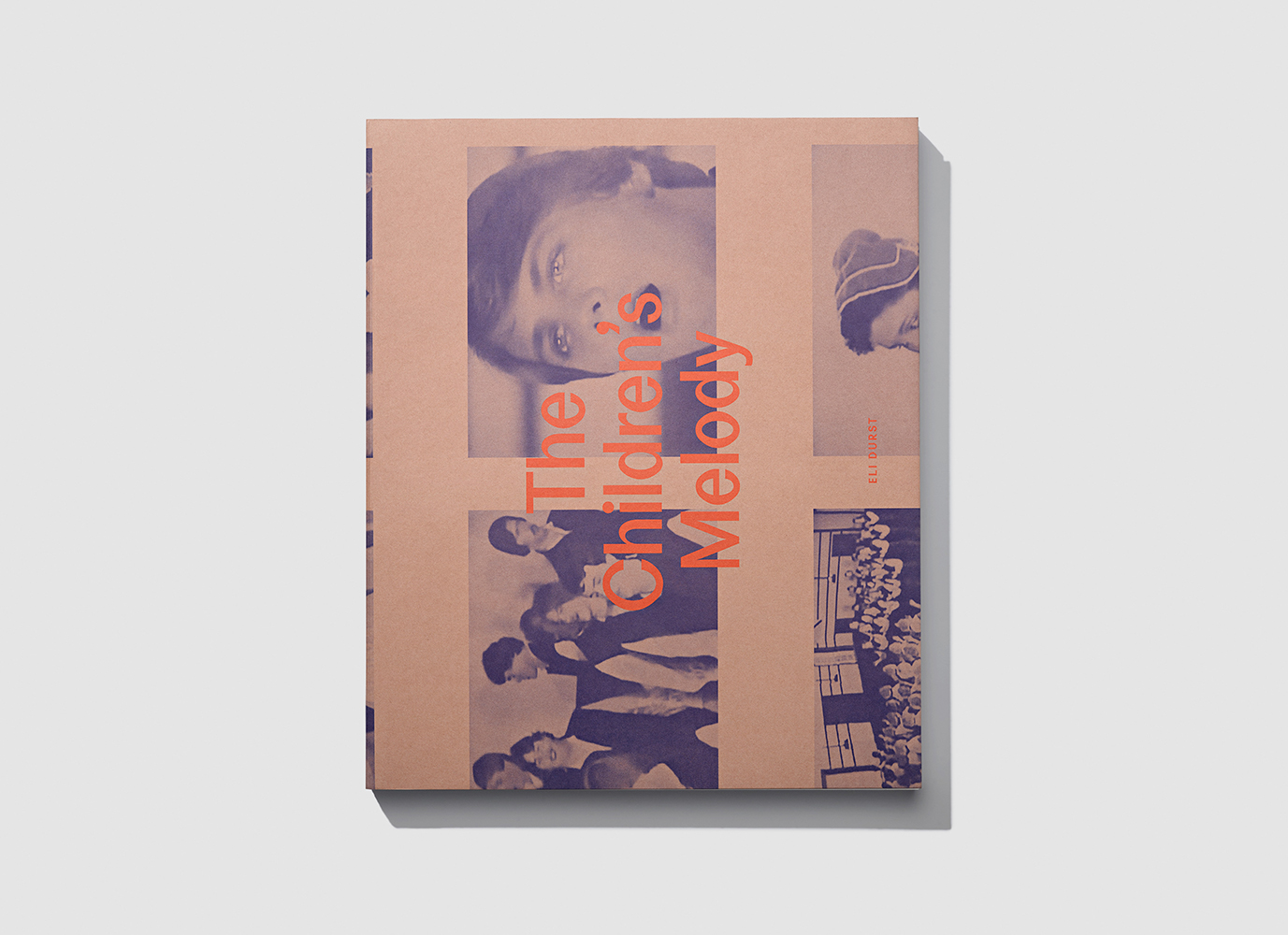

Eli Durst: The Children’s Melody

I first met Eli Durst a few years ago when we spoke about his work centered on adults negotiating faith, purpose, and community. His new book, The Children’s Melody (Gnomic, 2025), continues that inquiry but turns its gaze earlier, to the fragile stage when identity is still taking shape. As someone who has long been drawn to the complexities of coming of age, both in my own photographic work and in watching my son (also named Eli) navigate adolescence, I’m fascinated by how Durst frames these early rituals of belonging. Set in cotillion halls, ROTC drills, and dance rehearsals, his photographs reveal the discipline, pressure, and quiet absurdity that accompany our efforts to both realize our individuality and to move in harmony with one another, all the while asking what is lost or gained in the process.

The following is a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Eli Durst.

TLC: First off, congrats on new baby Lucia! How does Roman feel about having a sister?

ED: Thank you, and sorry, in advance, if I sound totally incoherent. Or more incoherent than usual. Lucia is doing great and Roman is so excited to be a big brother, or “huge brother” as he says. He’s maybe a little overzealous at times. But in general, it’s really sweet to see.

TLC: Your previous books focused on adults figuring out faith, identity, and community. The Children’s Melody feels like it continues that investigation but steps earlier in the cycle, toward the moments when those notions and needs first start to form. What pulled you to that earlier stage? Do you think being a dad has anything to do with it?

ED: I don’t think I was thinking explicitly about being a dad when I started to make this work but looking back, it must have played a part, especially considering that the work dovetails exactly with the birth of my first child. I started thinking a lot about how something as raw and chaotic as an infant slowly becomes a member of a group, a tribe, a society. And also tripping out about how the decisions that I make, the things I say, the behaviors that I model, might shape this little human.

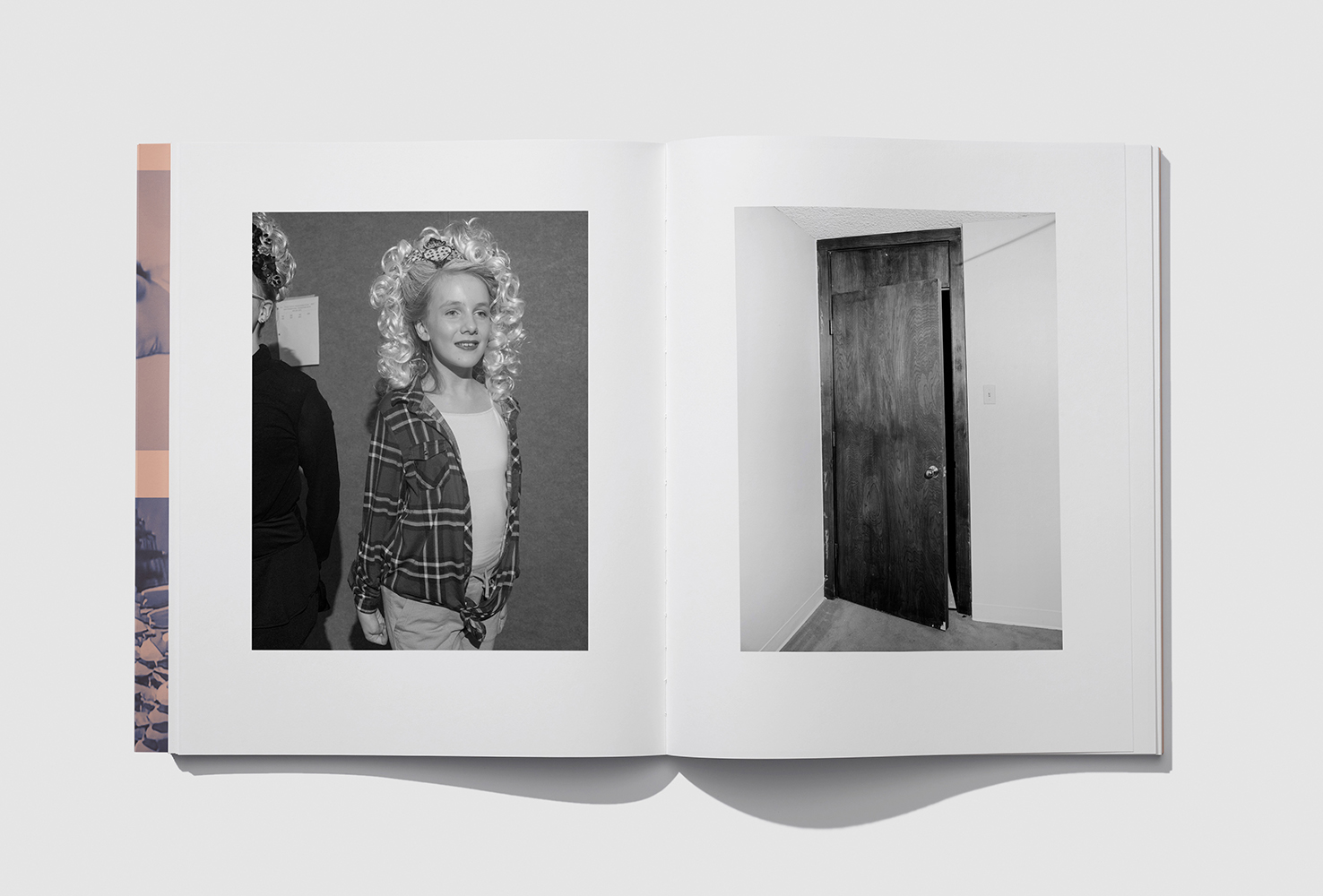

I also think looking at younger people—loosely defined in the series as kindergarten through college—was a natural step because their identities seem less calcified than adults. Many of the young people that I met and photographed seemed so genuinely and earnestly invested in figuring who they want to become, how they should be and how they should move through the world.

TLC: Yes, that process of becoming! After my son (also Eli) was born, I started being very curious about how we as humans build personal identity. I read Erikson’s work on stages of development and there was this interesting theory about adolescence, that during this phase we build an understanding of ourselves via how we are viewed by others. This is the time of our lives where people often ask “What do you want to be when you grow up?” We start to see ourselves as having to serve a role within society to be valid and seen. It’s so fascinating to me and also kind of sad.

And so of course, like you, I wanted to explore this photographically. When I started making pictures of teens, I noticed how rapidly they were changing, their bodies, their minds. They were so mercurial, the photograph I took one day felt irrelevant the next. How does your experience photographing young people relate or not? Are you trying to get to the essence of their individuality or are you seeing them more as archetypes, the role they are playing?

ED: I think your question cuts to the heart of what interests me most about photography: photographs are, simultaneously, indexical documents and total fictions. A paradox: the more specific and more accurately they describe the world, the more they can mean something else entirely, the more effectively they become metaphors or symbols. It’s why photographic clichés, like stock images, make the least compelling pictures.

This is all to say that I think the pictures work best when they depict both individual people and archetypes, or vessels onto which the viewer can project their own ideas. I photograph out in the world because I love how the world resists my simplistic ideas, challenging reductive theories or concepts.

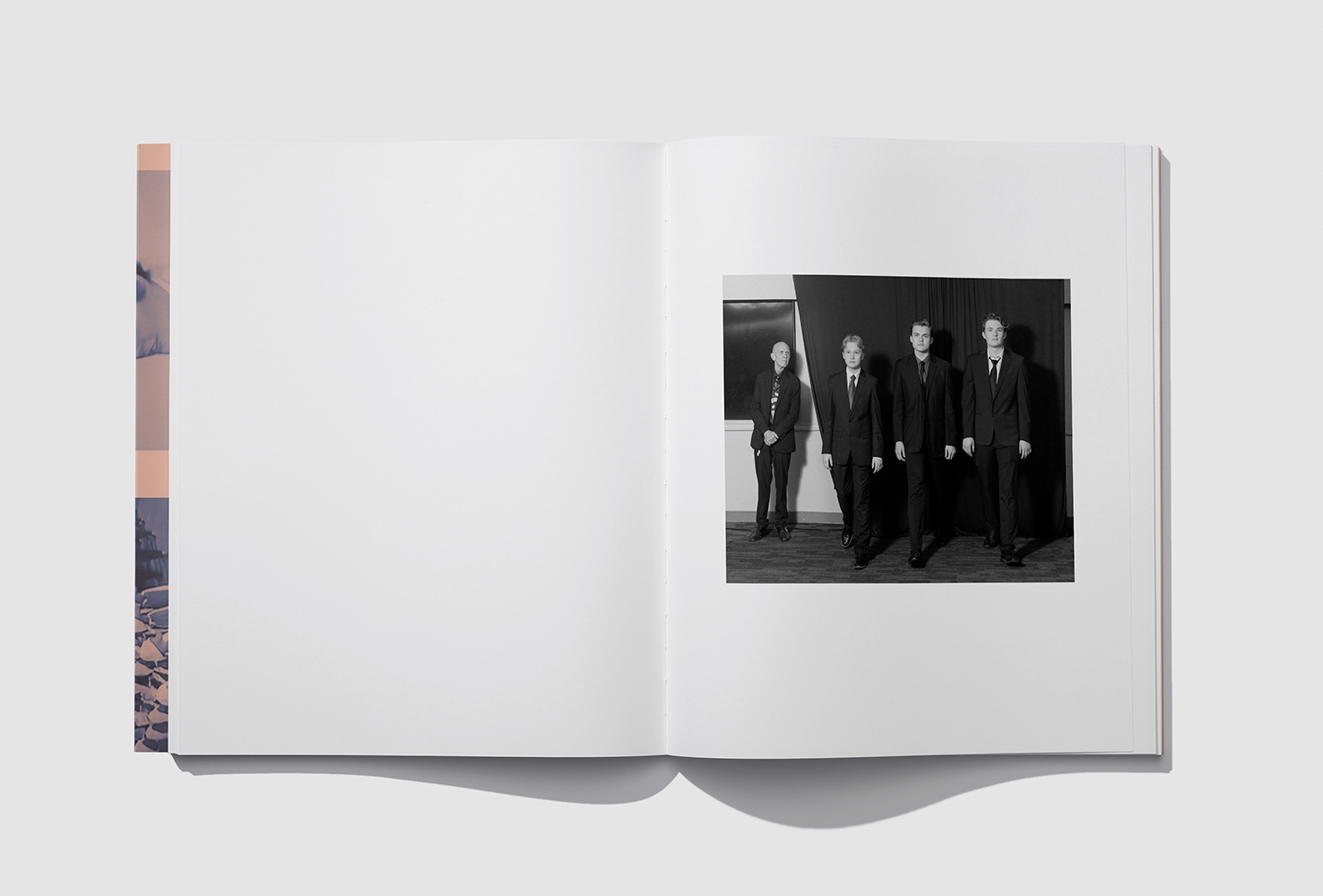

For example, as part of this project, I spent about six months photographing several cotillion groups in Austin. It turned out to be a pretty divisive subject. I had my own ideas and biases about cotillion as a means of reinforcing regressive ideas about gender and class—ideas that still hold true in some ways. But I also met a lot of wonderful young people who wanted to learn social skills or how to dance or how to talk in front of a crowd or boys who wanted to be able to talk to girls. The world is much more complex than my own ideas about it and photography can capture, or at least point to that complexity.

TLC: I can see what you mean about complexity,.. there’s a strange mix of sincerity and absurdity in these pictures that, for me, brings a sense of unease. Maybe this unease comes from knowing the stakes are actually quite high. These kids are our future.

Can I ask a technical question?… How are you lighting these scenarios? I am interested in how you see the flash-style playing a role in this complexity. It seems to freeze the action at (dare I say) a decisive moment with stark detail. The photograph takes me away from how I would naturally experience the moment and makes it a whole other thing. Can you talk about this choice? What is it like in the room when you are photographing these kids?

ED: When I shoot, I have a radio signal mounted on my camera that triggers off-camera flashes. I usually shoot with one to three flashes—they vary in size depending on the size of the space where I’m shooting. Having them off camera allows me to move them around the room and experiment with really strange and unusual lighting conditions. I had a student once who told me he had learned in a lighting class that lighting set ups should feel naturalistic. I guess I’m trying my best to do the opposite.

I hope the light creates an uncanny feeling. I hope it defamiliarizes these quotidian spaces so that you have a sense that you’re seeing something in a new way or for the first time. I hope it allows the viewer to appreciate just how strange the world we’ve built for ourselves is.

Shot with strobes and being black-and-white, the photographs look almost nothing like the world did when I fired the shutter. When I show images to the people in the pictures, they are almost always shocked by how different the photo is from their memory of the event. It’s a reminder of how photography is an act of transformation.

TLC: Photography is totally an act of transformation! I also see this transformation working through where you decide to place the camera. Like, for instance, the dancer photograph, she’s in her zone having this internal experience of embodied practice, while simultaneously there are iterations of her in the mirrors that can only be seen from the camera’s position. We see her multiple selves, she doesn’t. Even the pictures up high on the wall… more repetition! A photograph seemingly allows for an objective stance because it’s viewing an experience from the outside. But we both know there is no objectivity. That’s a choice. The photographer’s choice. The camera allows us to add all this complexity into a real-life moment. And the viewer can then attribute whatever meaning they want to project, the transformation builds.

That multiplicity happens again in the photograph with the uniformed individuals (ROTC?) all lined up.. and then with their hands raised it adds another layer of volunteering for this military experience. At least that’s how I read it. I am interested in your reading of these images… Do similar meanings come up for you? Do you think of these meanings while you’re shooting or more so when editing? How does sequencing play a role in building this complexity and meaning?

ED: The image of the young girl levitating was taken at an Irish Dance class—she was practicing for an upcoming competition. I think that image is a great example of how sometimes that photographic transformation we are talking about can be a result of how differently the camera perceives time than we do. A moment is frozen in time that only existed for a fraction of a second. The camera allows us to scrutinize this young woman floating much like the mirror allows us to see her from multiple vantage points. (The row of framed headshots reminded me, in a comedic way, of venerated elders looking down at the dancers, judging them, demanding perfection.)

Many of the images in the book, including these two, depict rehearsals for some kind of final performance. (The Air Force ROTC students are practicing drill, which is where they march in formation.) The final performances, whether it’s an Irish Dance line or military marching, are both meant to convey a sense of effortless control and perfection. That’s why I’m much more interested in the practices and rehearsals because they undermine the illusion of perfect uniformity, exposing the labor that goes into creating these performances.

For example, in this image of a cheer team, the young women at the top of the pyramid are meant to project an air of athletic grace and confidence. As your eye travels down the frame, you see the women at the base of the pyramid and you see the strength, effort, and struggle that are required to maintain this illusion. And, hopefully, you also sense its precarity, that it could all come crashing down at any second with the slightest misstep.

TLC: Even with the camera and all of its tricks and transformations, the real-life pressure of these scenarios is palpable. I am curious, were you on a team or in a club as a kid? (Did you experience any of this pressure or do you imagine kids have it different these days?)

ED: I was completely obsessed with basketball as a kid and also played tennis pretty seriously through high school. It was abundantly clear that I didn’t have any kind of future in sports, but I do think being part of a team was formative. What’s funny is that I wasn’t part of most of the groups that I photographed, cotillion, boy scouts, ROTC. I think at the heart of photography, at least the type of photography that I’m interested in, is just a curiosity about the world. It’s a reason to be somewhere you wouldn’t have any other reason to be.

You have a teenager. Are these questions that you thought about when raising Eli? How to foster a sense of individuality but also a connection to a group or community? Or is that something that comes from the kid.

TLC: My Eli is fiercely independent, his only program is his program. I have always appreciated that about him but I have also wished for him to feel a sense of camaraderie and collaboration that comes from working together as a team. When he was younger, I tried to get him into team sports to no avail. But then I remembered my own coming of age as a skateboarder, even these kinds of “ individual sports” come with their own sets of social cues and rules, it’s just less formal. I think as humans we crave both the belonging in conformity and the singular self of individuality. It’s funny, Eli is in high school now and he goes to a school with uniforms. Every other day I get email notifications that he has detention for wearing a hat or the wrong color pants. We BOTH roll our eyes, but he has to suffer through the real tangible consequences for not fitting in.

Speaking of fitting in, how do you feel the photographs fit together? As you are sequencing, are you finding themes that stretch across the different scenarios? How did the edit and sequence come together? When and how were Gnomic involved?

ED: With this project, because I’m photographing all these disparate groups, I think the edit and sequencing became extremely important. The edit hopefully allows the viewer to see the commonalities between all these different organizations and activities; to see the shared desire to belong, to be part of something.

I am kind of a control freak when it comes to my photographic process, but figuring out the edit and sequence is something that I’m always grateful for help with. In my opinion, I think it helps to have someone outside of your own head think deeply about how the pieces fit together, much like movie editors. The final edit and sequence is very much a result of working with the team at Gnomic, especially Shane Rocheleau and Jason Koxvold. We collaborated over a long period of time, sending edits back-and-forth. What we ended up with is pretty far from where we started. Much like the design of the book (by Jason Koxvold), I was surprised by the final product, in a great way.

How did you deal with edit and sequence for A Poor Sort of Memory?

TLC: Similarly, where I started was far from where it ended and with help along the way. I feel the value in seeing the work through someone else’s eyes. Not when I am making the pictures but afterward. I love when someone else has a completely different read than what I intended and I love the sparks of insights that come from the dialogue.

Like the individuals in your pictures, I feel like when we are making photobooks we are seeking both individual distinction as well as belonging. We want to express something but singular be part of this rad community.

One last question about your book,… can you talk about the cover. There are so many surprises!

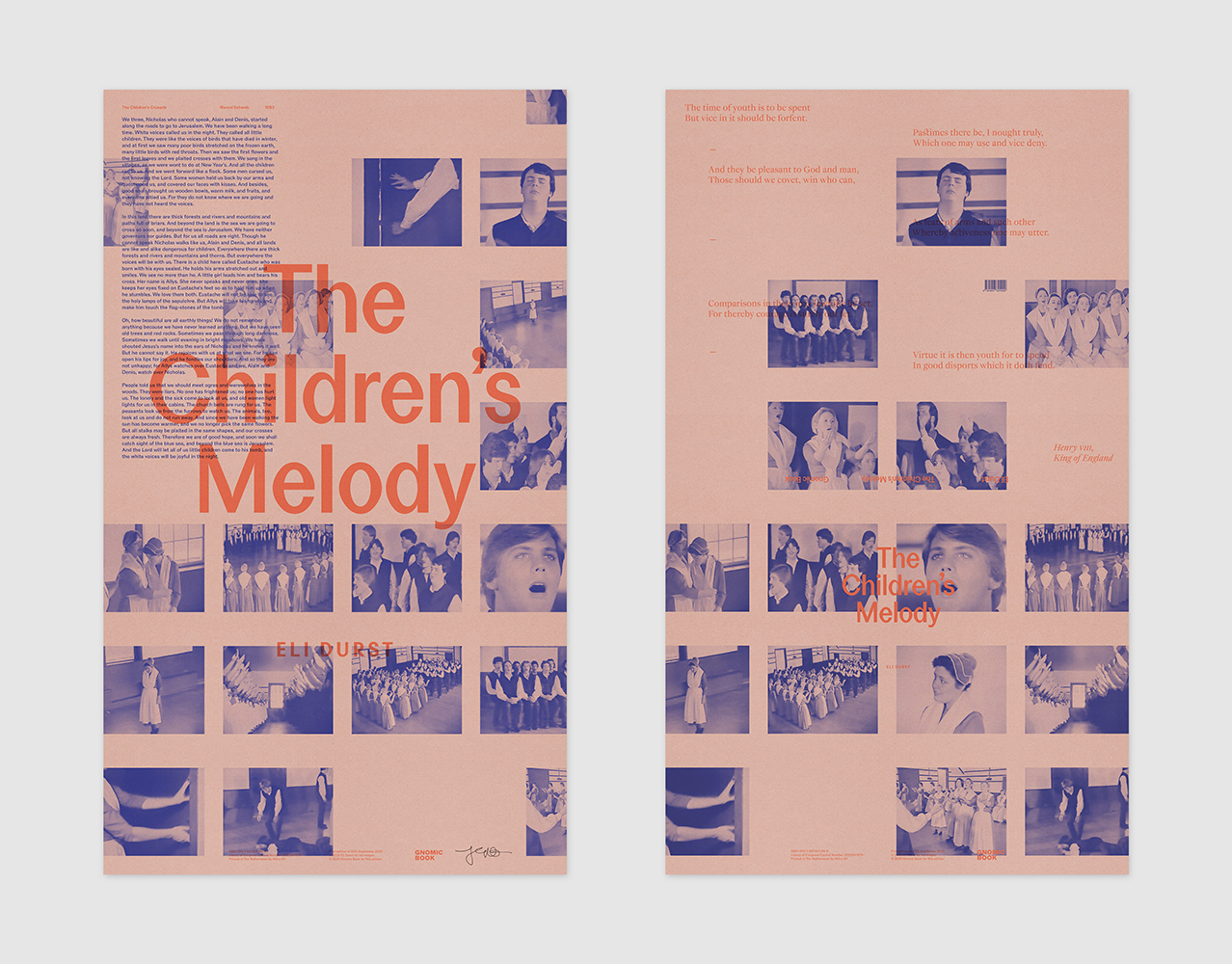

ED: Credit for the cover goes to Jason Koxvold at Gnomic—he’s a brilliant designer. We wanted something unique and impactful and I think he nailed it. The cover unfolds into a double-sided 560x950mm poster. There are two texts on the cover but you can only read them if you take the cover off and unfold it. One is a sonnet about the importance of virtue in youth written by King Henry VIII—which feels extremely relevant to current events—and the other is an excerpt from Marcel Schwob’s bizarre tract The Children’s Crusade. (Side note: Marcel Schwob’s niece, Lucy Schwob, better known by her art moniker Claude Cahun, would become hugely influential to photographers like Cindy Sherman and Gillian Wearing.)

I like the idea that in order to read the text, you have to physically remove the cover. Under the maximalist cover, the book itself is much more minimal. We left the spine uncovered to give you the sense that you’ve sort of pierced the façade and now you’re looking at the book’s guts.

The images on the cover are 35mm photographs that I made of a video of a 1970s recreation of a Shaker ceremony by the University of Kentucky Choir. These images are very much connected to the photographs in the book but despite various attempts, they never felt quite right alongside the interior images. Including the images on the cover/poster was a solution to this problem. It allowed the images to complement each other without forcing them into the same envelope. I like to think the cover can live on its own, as a sort of zine.

TLC: The book’s design seems to echo its themes, how ideals are performed, concealed, and then peeled back. And the title, The Children’s Melody, suggests a collective harmony, a kind of moral or cultural tune we all grow up learning. But it also feels a little ominous. Is there something specific you are referencing?

ED: The title of the book is a riff on a concept from communist China called zhuxuanlu or a “central melody” of life. While some level of independence or deviation is acceptable, everyone should exist within certain morally and politically acceptable parameters, in a kind of productive harmony. I liked the idea of transposing this idea onto a society that thinks of itself as the polar opposite of communist China.

TLC: A sharp inversion for sure. And the melody is haunting… Like a song you can’t get out of your head.

The Children’s Melody by Eli Durst is available from Gnomic Books. The hardcover book is bound inside a poster (also available separately, unfolded and signed) with historic texts by Marcel Schwob and the King Henry VIII.

Eli Durst is an American artist whose work explores the social forces and group dynamics that shape the suburban American experience. Durst’s photographs have been exhibited internationally and have been featured in Aperture, The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Vogue, and The Atlantic among others. He has published three monographs: The Community (Mörel, 2020), The Four Pillars (Loose Joints, 2022), and The Children’s Melody (Gnomic, 2025).

Durst lives and works in Austin, Texas, where he teaches at the University of Texas College of Fine Arts. Durst has received numerous prizes, including the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize, a 2017 Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship Grant, and a 2025 Guggenheim Fellowship.

Follow Eli Durst on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA. Her monograph A POOR SORT OF MEMORY is now available from Deadbeat Club.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026