Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La Man

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

In Sha La La, Man, photographer Kevin Klipfel turns the camera inward, using family photographs, vernacular snapshots, and newly made images to grapple with time, memory, and the quiet terror of impermanence. Sparked by a return home to New York after more than a decade away, the book unfolds as a visual reckoning with inherited identity, loss, and the people and places that shape us. Moving fluidly between past and present, professional practice and amateur gesture, the work resists polish in favor of intimacy, embracing imperfection as a way of staying human in an increasingly artificial world. In our recent interview, the artist reflects on the emotional and philosophical origins of this deeply personal project and how it became a meditation on what it means to love, remember, and be present.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

Kellye Eisworth: How did this project begin?

Kevin Klipfel: When I described the feelings that motivated the project to a friend she used the phrase “time sickness.” I felt dislocated in time and like I was running out of time and it made me sick. These feelings began after I spent Fall 2024 back home in New York, in both Buffalo and Manhattan, where I hadn’t spent an extended period of time since moving to Los Angeles over a decade ago.

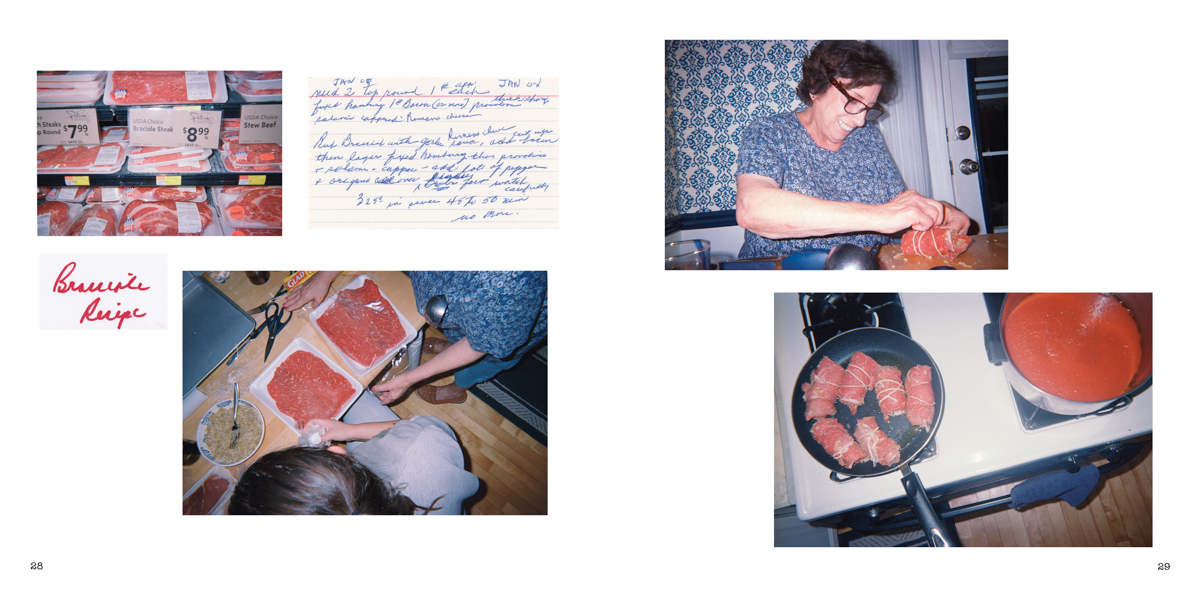

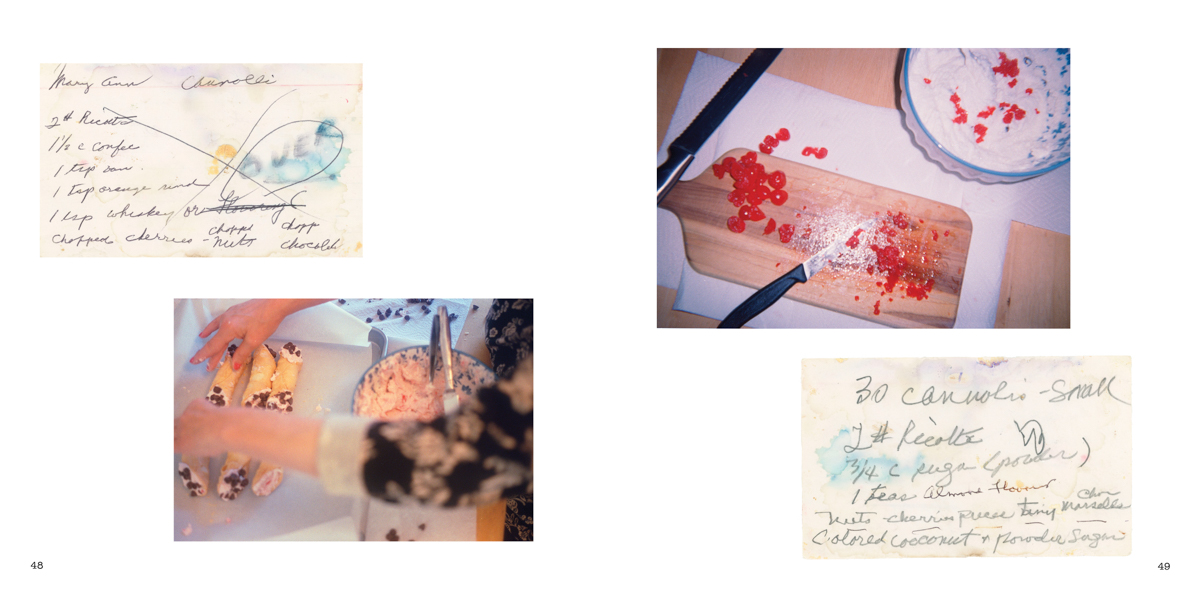

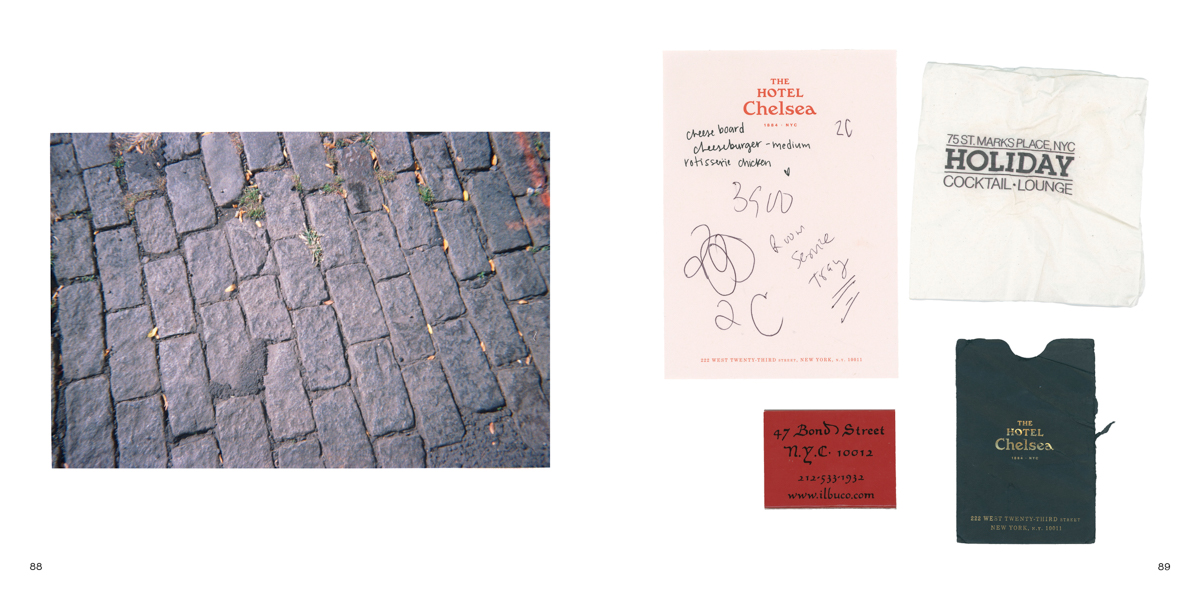

My mom was beginning the process of moving into a retirement community and part of the reason my wife and I were there was to help her sort through the things in her house. I was raised by a single Mom and spent a lot of time with my maternal grandparents, who were Italian-American. On this trip I wanted to take pictures while we cooked some of my Nana’s recipes she made when I was growing up – braciole, cannoli, Italian-style cutlets – so we’d have mementos of these traditions. I also took pictures of places in Buffalo where my family had gone for decades, like Scime’s, a family-owned Italian pork store where my Nana would buy cutlets. I did the same for local places that meant a lot to me in Manhattan in the East Village, the Lower East Side, and at the Chelsea Hotel, where we were staying. It was like a personal photo diary.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

The morning we flew back to LA I felt sick. Thinking about the people and places I love not existing and the time I’d missed living in California literally made me nauseous, the way you’d feel sick to your stomach, but inside my brain. I felt like time had passed me by and suddenly I couldn’t abide a world where I couldn’t knock on my Nana’s door and make cutlets and cannoli. It overwhelmed me that pretty soon all these unique, family owned places would soon be gone, replaced by generic corporate culture. It would be like they never existed. I felt crushed by feelings about life’s impermanence. It felt urgent to record these people, places and traditions.

This time sickness altered my perception. After this trip I was never the same. It’s similar to how people here in LA will go out to the desert to take mushrooms or ayahuasca to manufacture a psychedelic experience that expands their mind or permanently alters their consciousness. It made me question reality in a similar way. What was real? Which relationships in my life were mostly transactional? What’s important once you realize we’ve turned almost everything into a commodity? After you realize the emptiness of seeking self-worth through external validation? What’s left to hold on to? The nausea of this time sickness broke something in me and forced me to confront these questions in a way that wasn’t abstract. The project grew out of not wanting to forget these experiences. Those are some of the questions it raised for me that the book might also ask of the viewer.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

KE: So in the book you incorporate images and artifacts from your family archive as well as the new photographs you made during this visit home. What do you think each of those two things bring to the work, and how do you see them in conversation with each other?

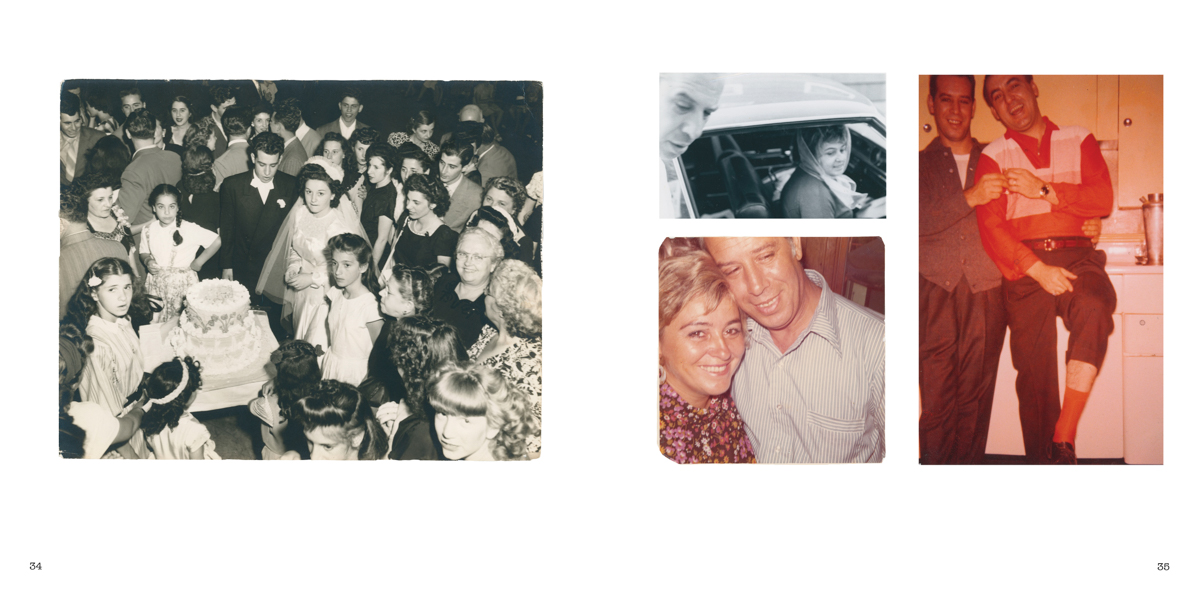

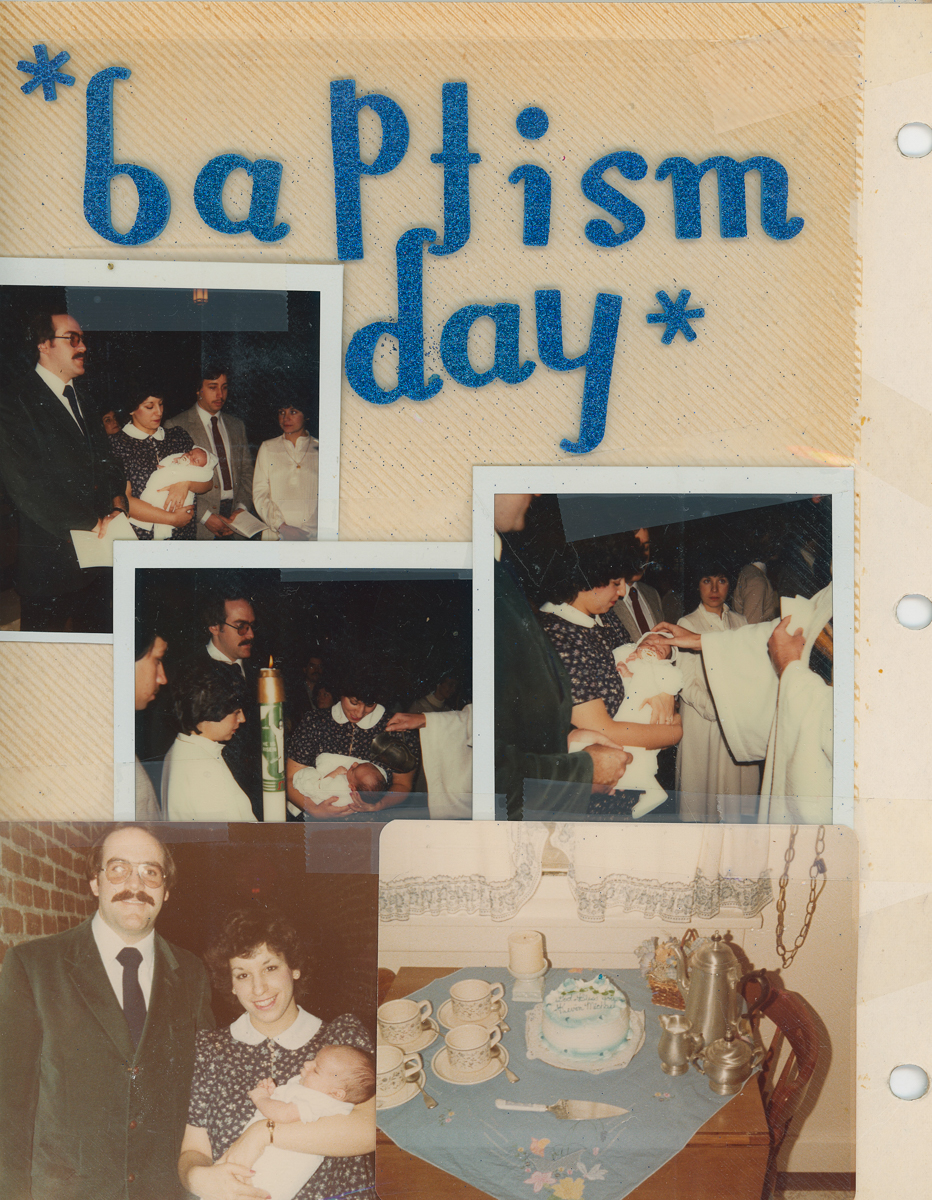

KK: Part of the process of being back home was sorting through my mom’s things and figuring out what to throw away, what to keep, and what I’d take, because she had to downsize. So it was like, “Hey, do you want Uncle Vinnie’s whiskey decanter and highball glasses? What about Nana’s dinner plates? You don’t want your St. Paul’s Tiger’s baseball trophy from 1993?!” That whole process. The main thing I wanted was our family photographs. When I got back to LA my mom sent me “my” photo album with photographs of my life taken by my family. She had taken a lot of time and care to edit it and organize it chronologically from the time I was born in 1981. That photo album my mom made inspired the whole project and eventually I had her send me even more family artifacts.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

The idea to put the family archives in conversation with the new photos I took on the trip emerged from a specific set of images in that photo album. A huge part of the identity of being a Buffalonian is being a fan of the Buffalo Bills football team. It’s central to the culture. In the family album there was picture after picture of me in Bills gear over the years — me opening a Bills football helmet that I got for Christmas, a picture of me in our backyard riding a skateboard in that helmet, page after page of football shaped birthday cakes and different Buffalo Bills themed birthday cakes. I was struck by the cumulative effect of these images and it raised so many questions about how family and place constructs our identity before we even have a say in the matter or are able to choose for ourselves who we are. Before I could even talk it was decided for me that I was a Bills fan. This was more emotionally complex than it might seem. When I was a little boy I loved the Bills so much but as an adult it was something I rejected because I associated it with loss and heartbreak. During some of the most formative years of my life, from ages 8-12, the Bills lost four Super Bowls in a row. At the same time my parents divorced and it broke up my family forever. We grew up watching Bills games together and it meant so much to me and after the divorce it was something we never did together again. And to this day, all these years later, all these miles away, if you tell someone you’re from Buffalo, they want to talk to you about the Bills, even if you say you aren’t a Bills fan. Which is what I always told everyone and it was always a lie. Deep in my heart I always was. It was just too painful to keep being one. It represented so much heartbreak.

The photo album made me think about how my identity was constructed and shaped by these outside forces. As an adult I’ve always had an existentialist sense of self creation, I believed that I could just decide who I wanted to be, that I could move away from home and forget about the past. The Bills photos made me realize how unnuanced a position that was and that philosophical sense of identity seemed a lot more like self-rejection, running away from myself and refusing to deal with certain painful elements of my childhood, rather than some liberated sense of philosophical freedom. The past was still living inside me and it was a huge factor of the time sickness and the hopelessness that wouldn’t go away once I was back in LA.

At the same time I was going through the photo album I was scanning the pictures I’d taken on the trip and I started to realize that lots of the photos I took reflected the same identity markers in the photo album. The similarities were everywhere, whether in the “Bills Mafia” sign on the lawn of my Mom’s neighbor’s house, or in the Italian food that we cooked. I started playing around with juxtapositions of the older family photos with photos I’d taken. They seemed to naturally go together. That’s how I got the idea of putting the images in conversation with each other in a book similar to my mom’s family album. There’s something strange about looking at a photo album someone else put together of your life. Some of it I identified with. Some of it seemed forgettable. A lot of important things were left out.

I became interested in what the photo album of my life would look like if I made it myself. What would that self-portrait look like if it reflected my own point of view on my life experience? Each set of images — the photos from my past taken by others, and the photos I’d taken in the present — added a completeness to that self-portrait that was not possible without putting them in conversation. I didn’t think anyone outside of my family would ever see it. I was just working through these issues.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

KE: Tell me about your decision to carry over the snapshot aesthetic into the new images you took for the book. I know you set strict technical parameters for yourself both in the way you made the photographs and the way you presented them in the book, and I’m curious why you felt it was so important to approach the work that way.

KK: I love the amateur quality of my family photos — their imperfections of exposure, the off-kilter compositions, the accumulation of dust, the papers they were printed on — and much preferred the look of them to digital photography or digitally enhanced analog photos. I think a lot of modern professional films are so saturated they almost seem digital. They look “too good” to me. I have always wanted the images I take to have the same look and colors as these drugstore family photos taken using non-professional film cameras on consumer grade film. When I was making the project I had a distinctive sense that I was creating an analog object. Film photographs aren’t intended to be viewed on screens. I wanted to remove the digital artifice and present the photos as straight from the negatives as possible.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

I took that concept to the extreme. I dropped off the film to be developed like you would at a drug store when I was growing up and then I scanned the photos myself with a cheap 35mm film scanner so they wouldn’t be altered. I scanned it all at zero saturation, zero contrast, zero exposure, and never made any adjustments in Lightroom or Photoshop at any point. It felt important to me not to edit them like you might alter professional photos by increasing the saturation or adding filters to them like you might see on photos posted to social media. I got dust and fingerprints on some of the negatives no matter what I did. There was nothing I could do about it. Eventually I considered it a happy accident. It was all so personal anyway, why not have my literal finger prints on the pictures? In the end it just seemed right. Or perfectly wrong. The look of the photos in the book captures the exact image I’ve had in my head of what I wanted my work to look like that I’d never previously been able to achieve. Part of it was just a matter of courage. The time sickness eradicated the compulsion to make them stand out to other people on the internet. I just wanted to make something I liked.

KE: Do you think it changed the way you took the photographs?

KK: Absolutely. Another happy accident was that the Leica M3 I brought with me turned out to be broken. I was able to fix it eventually but something was wrong with the winding mechanism and it ruined the first couple rolls of film I took with it. I went to a store in Buffalo and bought a pile of those little green Fuji Quicksnap disposable film cameras with the plastic lenses. These are the exact same cameras I started taking pictures with as a teenager in the 1990’s that got me into photography in the first place. Most of the photos in the book were taken with these cameras.

They changed the way I took the photos because there’s a playfulness to those disposable cameras that brings me back to taking photos just because it’s fun and because you want to capture something personal. It makes taking photographs a little more intuitive because you’re less likely to sit there laboring over a composition. It only takes a second to take it out of your pocket, look through the viewfinder, frame it how you want, and put it back in your pocket. You capture how you actually see things instead of how you think you “should” see things because “I’m taking a picture now; I’d better make sure it’s artistic.” It gets you out of your head. That spontaneity shows up in the images and in the compositions.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

It also opened up more possibilities for the kinds of pictures I was able to take. I could take all those photos while making braciole, because I could leave the disposable camera on the counter while cooking because I wasn’t worried about getting sauce all over it. These cameras are also unobtrusive so an advantage is that people don’t take them as seriously as if you have a more professional looking camera. I could take pictures in businesses and public spaces where they might otherwise not let you take photos. They don’t think you’re going to “do anything” with the pictures. Also, people don’t pose as much for a disposable camera even if they know you’re taking their picture. The pictures of my mom and my wife wouldn’t have been possible with a different camera. They didn’t feel observed.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

KE: This approach has an interesting effect of flattening the sense of time in the work. Sometimes cultural signifiers reveal the time period in which an image in the book was taken, but it’s often hard to tell which photographs were taken by you and which were pulled from an old family album. Is the ambiguity intentional? How does it relate to the nature of time and memory as you see it?

KK: That’s exactly what I was trying to do. I was drawn to the idea of putting the photos in conversation with each other so that you might not be able to tell when they were taken or whether they were taken by me or someone in my family.

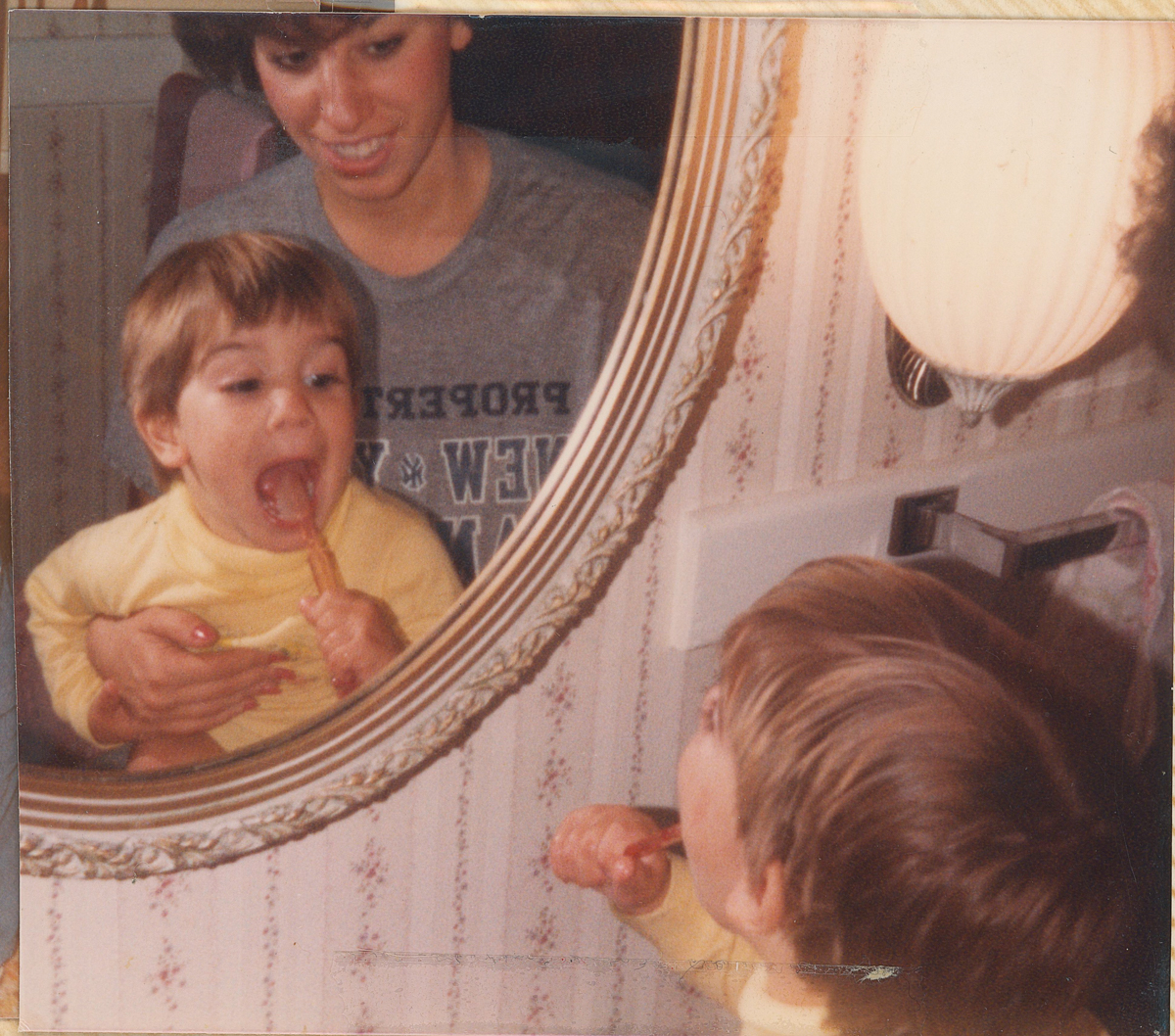

Part of it was trying to visually recreate the sensation I had of being dislocated in time. There was something physical about being back home that made time bend and made me feel like I was experiencing everything all at the same time. The past felt so alive. I didn’t have separation from my young mother in the Yankees t-shirt who appears in one of the photos holding me to brush my teeth in the mirror from the woman I was helping move out of her home into a retirement community. I saw that younger self in her still, down to the blue 80’s eyeshadow. There was no difference between the cannoli I was eating at my mother’s house for the last time and the cannoli my wife and I made with my Nana. Everything triggered a visual memory from the past. Going to Scime’s and making cutlets made me picture my grandparents; a Bills sign brought up the exact kinds of memories depicted in the family photos; and it was all visual, beyond language.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

Not being able to tell the difference between who took the pictures was also a way to raise certain philosophical questions about shared authorship, identity, and aesthetics. What questions might it raise if you couldn’t tell the difference between vernacular photography and fine art photography? To me, those family photographs are art. The photos I selected all share some of the same formal or technical qualities that might constitute a “fine art” photograph and the same was true to me of the “snapshot” photos I had taken. When curated in the right way, maybe the only difference was the impulse someone had to put what they were doing out there in the world and call it “art.” That was the feeling I had and something I wanted the viewer to experience by creating that ambiguity.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

These questions were also inspired by the dedication and care my mother had taken putting together my photo album. It moved me to picture my mother sitting there making “artistic” decisions about what photos to include and how to arrange them in the photo album. It made her so happy that I liked the book but what I liked about the book wasn’t just that it included photos of my life. I liked that she spent so much time crafting this personal work of art. It made me feel connected to her. She had all the same impulses I have as a lover of photography and “fine art” photo books. The main difference is that she isn’t as pretentious.

That made me think about the invisible labor and artistry of the women in my life. When I was a boy my mom spent so much time and care doing things to make my birthday special just because she loved me. She didn’t get any “credit” for it other than the joy she took in making me happy. You can see that joy in the photos included in the book. My mother-in-law spends hours sitting alone in a room making intricate quilts that require so much artistry and attention. These quilts are passed on to the members of our extended family but it’s not taken seriously as “art” by almost anyone and maybe even dismissed as missish. Both of these women create in a pure way just for the sake of doing it and without any expectations of getting something from it or even the pretension to call themselves “artists”. I find them inspirational and think we might have a lot to learn from them in ways that go beyond just the making of art.

That’s another reason why I wanted to present the photos in such a way that maybe the viewer couldn’t tell the difference between them. I didn’t really think there was much of a difference even though the authors of the family photos didn’t think they were making “art” when they took those pictures. To me they were and they were doing so in a way that might raise some really important questions about the nature of art. That’s what made a “fine art” photo book like Sha La La, Man a true family album to me. Who took these photos? We did.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

KE: In the introduction to the book James Martin talks a lot about the value of imperfection and human error, and I was wondering if you could speak to those ideas in the context of AI-generated images?

KK: The art I cherish the most — whether in music, film, painting, or photography — almost all seems to have in common what I think of as a punk ethos of amateurism, where it’s not slickness or technical perfection that matters, but self-expression, style, and attitude. I like things that are a little sloppy, or not perfectly in tune, and I don’t think you need fancy gear or equipment to make great work. Imperfection makes art real and raw and alive to me. It enhances rather than diminishes its artistic value. I’m in love with the idea of artists who can pick up a camera, or guitar, or whatever, and make something cool and distinctive and personal.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

Part of what draws me to the pictures in my family archive is precisely that quality of imperfection and human error. They weren’t taken by professional photographers. The people who took them probably couldn’t even name a fine art photographer. In fact, these pictures probably couldn’t even have been taken by professionals. They have compositions that no “professional” would decide on. They’d almost have to unlearn everything they’d ever been taught to see the world as it’s depicted in these images. But there’s something compelling to me about each of them that you can’t achieve by using an Instagram filter or Lightroom or Photoshop or AI. A photo in the book might be completely washed out but there was a baby blue on a birthday cake or a deep red on my uncle’s socks or a fantastically cut off composition of my mother holding me or a piece of scotch tape that tore the photo in the exact right place that I was completely blown away by. It’s the amateurism that makes them interesting and their uniqueness as irreplaceable objects that makes them something you can’t artificially replicate. In an increasingly artificial world that I felt extremely alienated from, and even sickened by, it seemed especially important to present images that highlighted this humanity.

These images reflected my sensibility but, as you picked up, the significance goes beyond aesthetics. I felt that their amateurishness raised interesting questions about what it means to be authentically human in the present. One of my favorite things about the introduction to the book is how it makes the case that staying connected to the imperfection and human error in these images keeps alive something important that can serve as a source of optimism and hope for the future.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

KE: What was the process of making the book like?

KK: I was obsessed with the editing and spent months and months experimenting with different layouts, sequencing, and selection of images. It was personal but I approached it like a curator. For example, many archival images weren’t included because they didn’t contribute to the artistry of the project and I would have included them if it really was “just” a family album. I approached it like it was a fine art photo book because that’s what I like to make and how I like to organize my work. I often make photo books just for myself and maybe send them to a friend or something but I approach it just as intentionally.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

The structure that emerged was somewhat linear. The book starts with arriving in Buffalo at my mother’s house and ends leaving the Chelsea Hotel in New York which is how the trip went. The book is divided into two parts: photos from Buffalo and photos from Manhattan. That basic structure mimics some of the elements around identity and choice we discussed earlier. There was the person I was given the circumstances I was born into in Buffalo whose identity I didn’t necessarily choose and there was the person that grew up dreaming of being an artist that felt a creative connection to the New York artists associated with the Chelsea Hotel. I needed to integrate the multifaceted aspects of myself in order to be connected to life in the present. There was too much disconnect.

Within that structure I wanted to create page layouts that were similar to a family album that progressed in a way that was diaristic and dreamlike and that visually reflected the dislocation in time I was experiencing. When I was starting to organize the project I re-watched Fellini’s 8 1/2. That film gave me some inspiration for how I might structure the book and some guidance for how I might select the images. The movie is “about” a director struggling with a creative block and his present mental health struggles trigger memories from his childhood. You see who is through his memories and all the while he’s processing the past by creating a film about his confusion. This is how I began to sequence the book organized around memory and time.

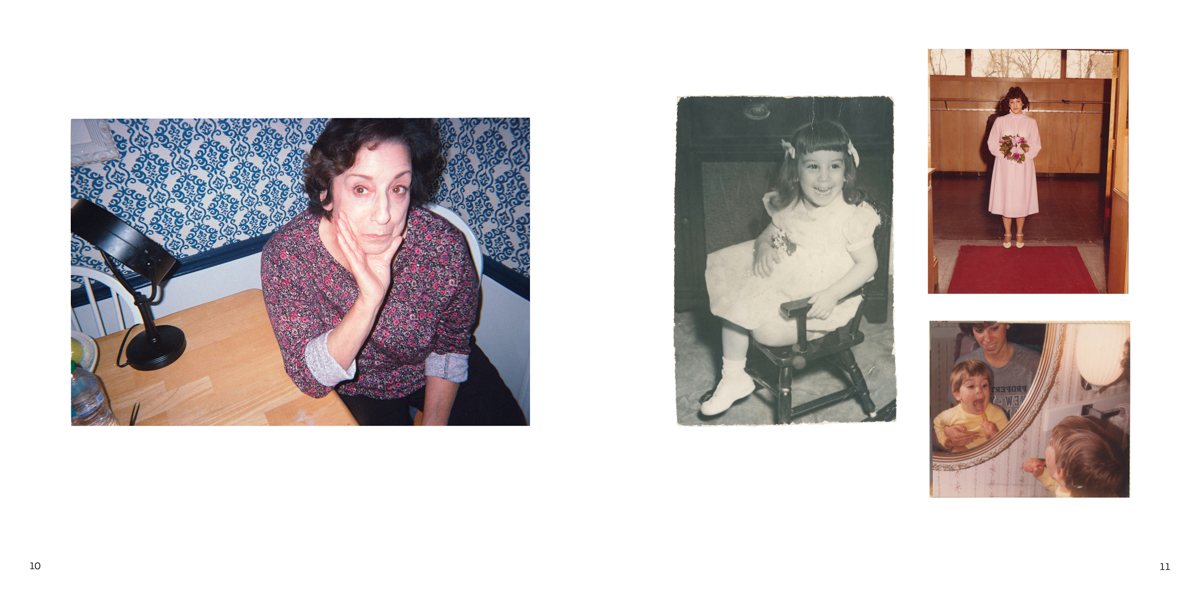

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

It begins outside my mother’s house, then introduces you to a page spread of photos of her. On the left is a photo I took of her inside her kitchen in the present. On the right is a family album-style collage of photos of her at different ages over time. This visually represents how I was experiencing time all at once. Often she was making the same faces. She might be a little girl or 70 years old but when she wasn’t posing — when she was being naturally herself — she had the exact same expression. I noticed the same about my wife and also about myself when I went through our childhood photos. These are some of the considerations that went into curating the images.

© Kevin Klipfel, from Sha La La, Man

KE: Tell me about the title of the book. It comes from a song, right? Why did you choose that particular line?

KK: Yes, it’s from the Lou Reed song “Street Hassle.” The song has girl-group inspired “Sha La La” choruses and that specific line is a response to how the things you love in life eventually “slip away.” I wrote that phrase down on a piece of Hotel Chelsea stationary one morning as I was listening to that record and thinking about the people in my life. I included the stationary in the book. For me it’s an expression of the bittersweet feeling that life is heartbreakingly beautiful. It’s a feeling that has something to do with the fragility of life, specifically around the impermanence of the things that we love. There is grief that comes from losing something that really matters to you, or knowing that you’ll lose something or someone eventually. That sadness comes from loving deeply, and living vulnerably, with an open heart. I’d give anything in the world to cook with my Nana again, but she’s gone and there’s nothing I can do about it. But it’s not hopeless. I can make her food and keep those traditions alive in my life, even capture images of making her cannoli or braciole recipes. You can’t live life being afraid to have your heart broken the way I’d tried to protect myself before this experience. You still have to root for the Bills. Love can make you cry. It is what it is. Sha la la, man.

KE: Wow, yeah, I can absolutely relate. What made you decide to put these personal images out in the world for others to see? What do you hope viewers will get out of the project?

KK: The funny thing is that this book couldn’t have existed if I had originally intended to put it out in the world for others to see. It would have been more of a performance. People would have posed. I would have been more self-conscious about whether the photos would be interesting to other people instead of documenting my experience without a filter. I wouldn’t have included family artifacts. I’d have thought that was stupid and nobody would care. I wouldn’t even have used the same cameras. Because of its personal nature, the book is a DIY family affair. My mother tracked down and sent me all the archival elements I needed to make the project. My wife helped with the layouts and graphic design. One of my oldest friends (who happens to be a philosophy professor who sometimes teaches philosophy of art) wrote the introduction. This made it special to me. It was my favorite thing. I still would have made a small printing for me and my family and the book would have looked exactly the same.

The biggest decision at the end of the process was whether to “publish” it by making more copies and having a publisher’s logo on it. I guess that makes it “real.” That external validation makes it, in some way, official. I suppose there was something important to me about that emotionally. To make it “official” was proof of existence. “I was here.” “Being here mattered.” I struggle with that impulse but there’s something so beautiful and human about it too. My Mom was here. My Nana was here. They were normal people. They didn’t seek out praise or recognition. But they were special. Their time on this earth meant something. I wanted to spray paint our names on the wall. For the so-called avant-garde. If there was a chance the book might reverberate with others who might “get it” I wanted it to connect with them. But the person I couldn’t wait to send it to was my mom.

What I hope viewers might get out of the project relates back to the title of the book. What’s life all about? What in this world is worth holding onto? If the book inspired viewers to reflect on, and stay connected to, what’s truly real to them in the present moment, they would have the same experience I had making the book. These are questions every person has to answer for themselves. But for me, when the chips were down, what kept me here were the people that loved me no matter what and the places and art and music and traditions I found most beautiful and true. Those were the only things that were real. Those were the things that made life worth living. I hung on to them for dear life and I’ve stayed connected to them ever since. I think faith in the future requires something that is beyond performance and the book invites the viewer to think about what that might look like.

© Kevin Klipfel, spread from Sha La La, Man

The intimacy of the photos might also inspire curiosity about the inner worlds of other people. I connect most to personal work that could only have been created by the person who made it. That unique glimpse into another person’s very specific way of seeing things is precisely what makes it universal. Only by being truly vulnerable and sharing ourselves with others can we begin to understand what another person is experiencing. Only then is authentic connection possible. That time sickness I told you about gave me a new perspective on the invisibility of suffering and the privacy of individual experience. During the time I worked on this project I often walked around the world with a nauseous feeling in my brain. It was maybe the worst thing I had ever experienced and I had to pretend that I was doing okay. It was the ultimate performance.

This pain gave me a deeper awareness of the depths of other people’s experience and the multitudes contained within each person no matter how average or ordinary we might think they are on the surface. It was a more profound perspective on empathy than I’d ever had before. During this period it was almost impossible for me to talk about what was happening to me on the inside. This project was the way I was able to process it and the work of other artists who had experienced similar things helped me see that I wasn’t as alone as I felt on the inside. To express oneself honestly is a very hard thing to do and art may be one of the only means we have at our disposal for doing so.

KE: Thank you for sharing such a personal story. I think this is a really thoughtful project and I’m so glad to share it with our readers.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025