Adam Ottavi: The States Project: Alaska

Alaskan Editor Ben Huff shares the work of Adam Ottavi

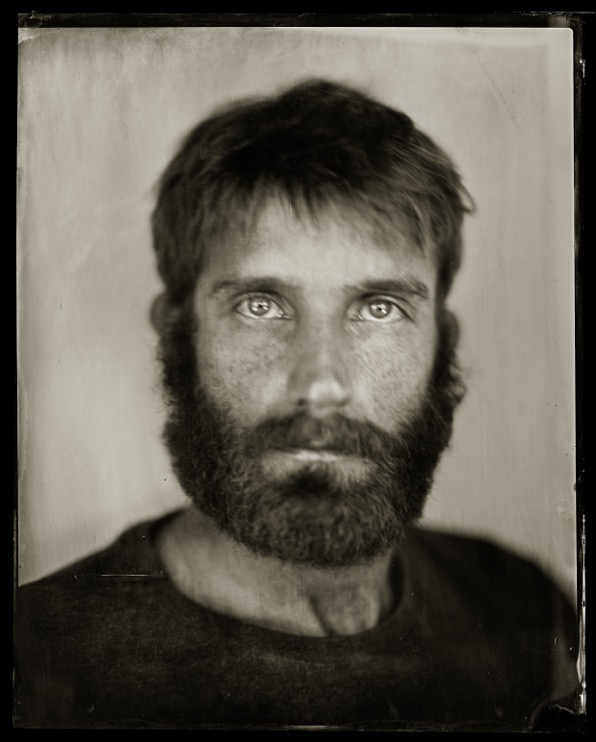

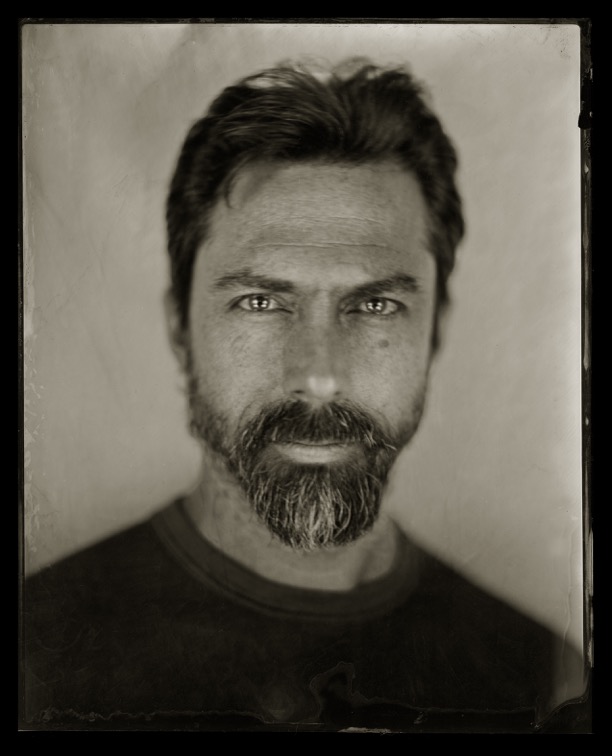

Adam Otttavi was the first photographer I met in Fairbanks in 2005. We were fast friends, and it turns out we both grew up in Iowa, less than a hundred miles apart. And, although we shared similar likes and shared a studio for a while, we couldn’t be more different artistically. And, I loved it. I was drawn to his commitment to portraiture, and his restless flirting with different processes. He was never afraid to take a risk. His recent work, Let That Fire Catch Me Now, is another evolution back to landscape. His call and response effort with the poet, and ex-firefighter, Kevin Goodan explores burned forests that influence the stunted forests of Interior Alaska and the smoke jumpers who fight those fires.

Adam Ottavi was born in Iowa in 1980. He currently resides in Fairbanks, Alaska. In 2012, Adam received a Rasmuson Foundation Individual Artist Project Award. His work has been exhibited nationally and is in the permanent collections of the State Museum in Juneau, The Museum of the North in Fairbanks, the Pratt Museum in Homer, and has been exhibited at the Valdez Museum and the Anchorage Museum of Art. His work was recently featured in Terrain magazine and is part of the 2015 viewing collection of Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon.

Your personal story illustrates the pull of this place ‐ do I have this right ‐ you studied at Columbia in Chicago, moved to Fairbanks several years ago, then left to work at a blue chip gallery in NYC, and then left the city to move back to Fairbanks. Explain what brought you back?

That’s correct. I originally came to Alaska to work on an art project in 2002. A visual diary piece on rural gay culture. I was fresh out of college. I worked on the project for two years then moved to NYC. In NYC, I worked for Gladstone Gallery. After a few years at the Gallery, working as an artist liaison, I realized that making artwork was a viable option for myself and my career. At Gladstone, I worked with a number of talented and successful artists and recognized the similarities in how we work. I am not comparing myself to the artists I worked with; they are incredibly talented, and I am merely hopeful for my work at this point. Witnessing their work ethic, methodology, and process gave me the confidence to venture out on my own. In short, at Gladstone I recognized I had a contribution to make to the art discussion and the creative means to do so. I was eager to return to Alaska mostly for the lifestyle and freedom. In retrospect, it seemed I had more work to do here, and also missed the simplicity and uniqueness of Alaska.

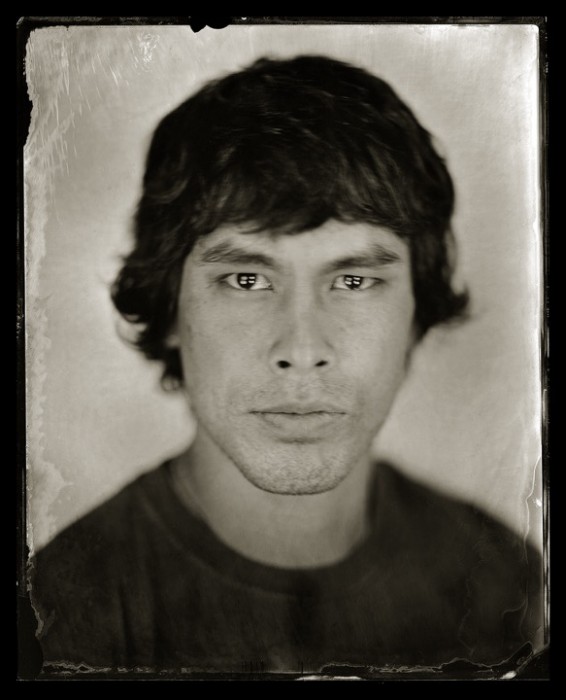

For the past several years, you have been making ambrotype landscapes and portraits. What led to the decision to go this direction?

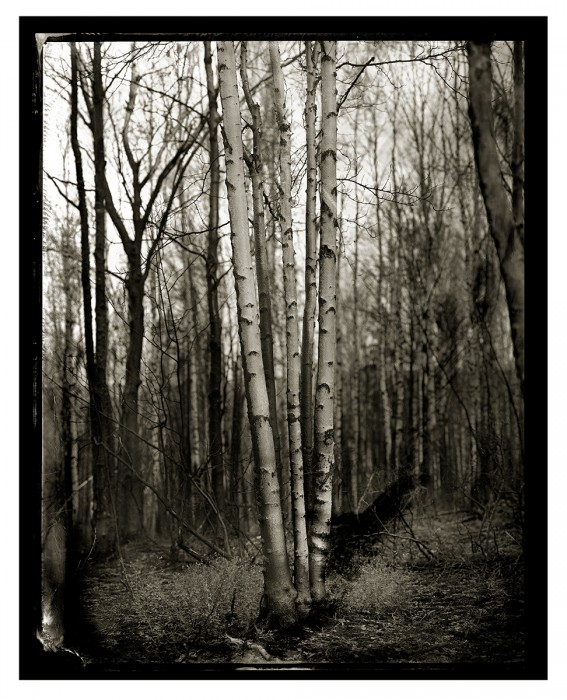

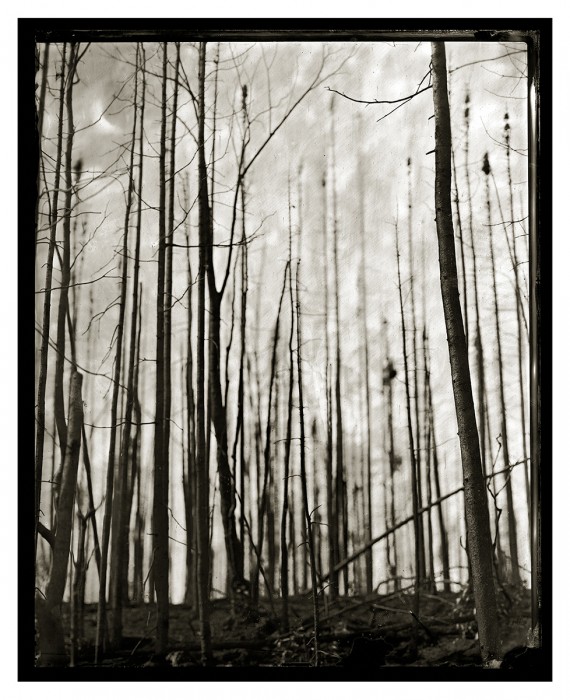

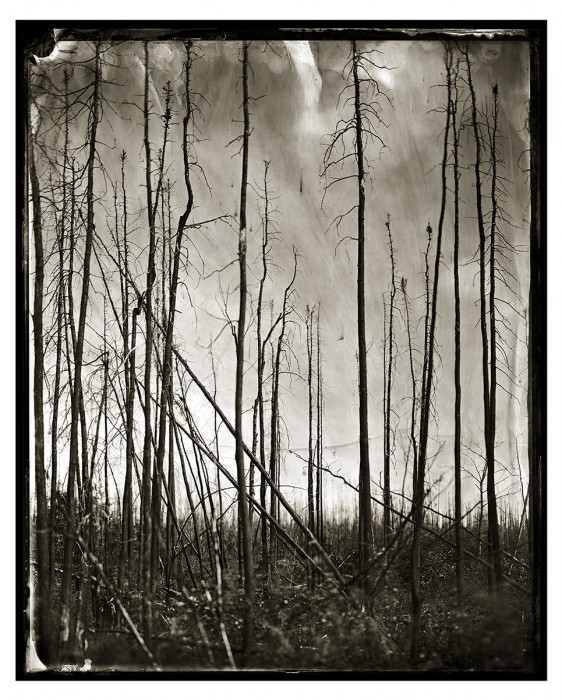

I began working with the wet-plate collodion process in 2009. At the time, I was frustrated with making images digitally and on film. Both were too easy and didn’t satisfy my physical desire to actually MAKE artwork. I need to sweat and toil more. Also, like other photo academics, I was curious to learn more about antique techniques. I began to understand the conceptual potential of the wet-plate technique in 2012 while making plates of burned forests around the Interior.

These landscapes – of wildfire ruins – seemed to record correctly with wet-plate. The subject matter and process make sense, work well, and fuse to create something new that transcends the novelty of the technique and the starkness of the charred landscape.

There is something so romantic about this way of working. Is there something about the landscape here that especially resonates on the glass plates for you?

The Interior landscape, as you know so well, is beautiful because it’s desolate and harsh. The valleys are cold and boggy. Depressing and mean. The trees grow with strained effort. Wildfire rips through and turns these trees into unforgiving spikes and needles. It’s dramatic.

This landscape makes for arresting and unfamiliar images and creates strange and close-knit communities. I suppose this happens almost naturally when your surrounding environment feels determined to overpower you. I think contemporary glass plates immediately question history and a sense of time, and the Interior landscape seems appropriately unsettled and rough in these pictures.

What has been the reception to this work in Alaska?

We just deinstalled the first exhibition of this work in Homer. Kevin and I were both present for the opening, and Kevin gave a public reading of his poems the day after. His reading was transformative.

It’s wonderfully different and inspiring to hear a poet read his work out loud. To hear each quick breath taken between stanzas. I liken it to experiencing an exhibition versus seeing an artist’s work online. It’s analog and fleshly. The community in Homer is vibrant and supportive of the arts. They received the exhibition with enthusiasm, and we were honored and grateful. Terrain magazine published a feature on the work at the same time and the editors replied with appreciation and praise. I think people enjoy seeing the photographs and poems together. I am eager for the book to be published for this reason. The work will seem more narrative in book format; humans seem to respond well to linear presentation.

You’ve said recently that you are considering moving back toward color and more narrative work. Can you speak to the need for this change?

Sometimes working with wet-plate feels like I’m speaking Victorian English to Nicki Minaj. It’s just plain silly and, unfortunately, obsolete.

Now, after working with collodion for the last six years, I just want to be contemporary and use the present tense, in part, by employing a photographic language that is current. I also think it’s time to challenge myself with digital and film photography again, and to summon myself with the process of just making pictures and working on a body of straight photographs. A book. A story. I’m trying now to create something that is absolutely true. Even though, this is near impossible with photographs.

Do you feel that community is important? What is your impression of the community in Alaska?

Yes, community is important. My community in Fairbanks has changed a lot over the past few years, however. And I’ve changed. I turn 35 this month and feel more inclined to work on photographs than to be social or play outside with friends. And although I’m not a snowbird, I spend a lot of time in California. I am part of a community there, too. I struggle with the art community in Alaska. On one hand, I’ve been incredibly supported and encouraged and enjoy how connected we are here. But there are conceptual limitations to what audiences in Alaska want, and consequently, my focus has evolved and my intent is now to exhibit outside. Alaska Native art is by far the most celebrated art form in our state. Alaska Native artists receive unmatched support from organizations, collectors, and the public. I’m envious of the community. Contemporary Alaska Native art is actually quite fascinating. Many prominent Alaska Native artists were not raised in villages or even within Native cultures, but they are Native by blood. Moreover, their artwork isn’t a product of tradition or cultivated craft. Instead, their work attempts to access their ethnic heritage by appropriation and promotion. And it’s accomplished through a combination of mediums via the culture of contemporary art. The interweaving is strange and intriguing.

How has this place changed or influenced your work?

I’ve worked in Alaska for ten years and have made five different art projects. I think living here gives me mental, physical, and emotional space and the time to be creative, internal, and productive. Being from Alaska also has opened doors for me, especially when traveling. People are intrigued by my work because of where I live. Even folks in Homer find Fairbanks to be exotic. And it is.

You travel outside often ‐ do you ever dream of living and making work someplace else?

Traveling keeps me sane and connected to what’s happening in other parts of the world. Big picture. And yes, I am considering moving in 2016. Ten years in Alaska might be enough. Although, if my work keeps taking me to other parts of the world, I’m happy to stay in Fairbanks for a long while. I have a great little life here. I still can’t think of another place I would like to live and make artwork, though.

Alaska is just so strange and beautiful. Sometimes I can’t believe that my life is here. And has been for so long. I’m an Alaskan now. It has been a surprising turn of events.

Is there a landscape in Alaska that has been calling you, that you haven’t yet seen?

I’m curious to see what will happen when natural resource production stops or slows way down. What will happen to communities here? I imagine it will be apocalyptic and fodder for some beautiful and poignant photographs. A good friend of mine, who has been here since before statehood, feels that this is already happening. I’m not interested in landscape images so much as communities, portraiture, interpersonal stories, and privacy. Photographs of these (more human) things are by far the most intriguing to me.

What’s next? Anything new you can share with us?

I’m working on a color project, currently. Truthful work about my life in Alaska and California. Lots of sex, money, and travel. End of the Roman Empire kind of stuff that’s perfectly enticing. Poisonous. Human nature. All the elements of tragedy and glory. I am calling the series Golden.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015