Chris Miller: The States Project: Alaska

Alaskan Guest Editor Ben Huff shares the work of Chris Miller

Chris Miller is all business. Whether it’s hanging off the side of a boat in Bristol Bay, or on the mountain, breaking trail ahead of his party, his commitment to the image is paramount. He is best known for his commercial fishing photography off the West coast of Alaska, but I’ve asked him to focus on his A River Divided work, and the opposing resources at play there. Chris is a friend in Juneau, and I see firsthand his dedication to documenting Alaska’s fisheries and the men and women who fish them. His personal project, A River Divided, begins to show the nexus of two important Alaskan resources and the complex relationship that exists – all with the romantic backdrop of the Southeast.

Chris Miller is a Freelance Photographer based in Juneau, Alaska, who focuses primarily on commercial fishing, backcountry skiing, and photojournalism.

Chris’ work has appeared in the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, the New York Times, Anchorage Daily News, Alaska Magazine, Newsweek, First Alaskans, People, the Daily Show with Jon Stewart, CNN, and various international publications and books. His work is also represented by Alaska Stock, the Associated Press, and Zuma Press photo agencies. His clients include Ocean Beauty, Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute, University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau Convention and Visitors Bureau, Copper River Marketing Association, Wholefoods, Schiedermayer and Associates, Grundens, Alaskan Brewing, and Patagonia.

Chris continues to commercial fish in Alaska, most recently gillnetting in Bristol Bay during the summer of 2014. Currently, he is working on a long-term photo project on the commercial fishery in Bristol Bay.

You were born in Juneau, went away to school, and returned to be a photographer – was it always your plan to come back?

Despite the fact that I wish I was a “true” Alaskan, only those who are born here can claim the honor; I was born in Portland, Oregon, and we moved up when I was three and a half years old. Despite my lacking of “true” Alaskan bona fides, I like to think of myself as an Alaskan first and foremost, and after 32-years I’d like to believe it is safe to say I am a local.

When I went to college in Massachusetts, at Clark University, I originally planned on going into government, possibly the foreign services overseas after graduating. My first major was in Government and International Relations, and I added my second major in Studio Art with an emphasis in Photography. Adding the double major my junior year required me to scramble to add credits to complete the major, which led me to take on a summer internship as a photojournalist at the Worcester Telegram and Gazette. After a summer covering daily news, everything from high school graduations to NCAA Division 1-hockey games, I was hooked on the professional lifestyle of a photojournalist and all the day-to-day variety it provides.

For better or worse my graduation coincided with the downturn in the newspaper industry, in the early 2000’s, and with an industry rife with staff and budget cuts it did not look like a possibility to get a position as a staff photographer. I returned to Alaska with hopes that given the size of the media market, I might be able to work as a freelance stringer in Juneau that would hopefully lead to a full-time position. As it turned out the local stringer who had worked for the Associated Press had just had her third child and was not going to be available to shoot the upcoming legislative session, which opened the door to many of opportunities in my first few years working as a freelancer.

You’re best known for your commercial work in Alaska’s fisheries, and you’re a fisherman yourself. What draws you to this lifestyle photographically?

Like many commercial fishermen, I have a love and hate relationship with fishing, but at its base, commercial fishing is one of the most honest and noble professions because our end product feeds the world. The work itself pits men and women directly against nature to at times push themselves to their physical, mental, and emotional limits to finish the day or the season. As it turns out, it can also be pretty lucrative work, and like many photographers I needed other work to supplement my photography. Ultimately, I am drawn visually to the extremes of the work and the remote locales it takes place in, but I am always attempting to counterbalance that with the notion of sustainably harvesting the renewable resource that is wild seafood.

I am taken with the idea that Paul Greenberg presents in his book, Four Fish, that fish are one of the last wild sources of protein that we can go to the grocery store and purchase. Just about everything we consume is grown on a commercial farm, pumped with hormones or genetically modified, and unless you harvest your own meat or have your own garden a consumer really has no connection with their food. Increasingly Americans and other countries are consuming more and more farmed fish and sooner or later genetically modified fish. The diversification of work in societies precludes us from being connected to everything we purchase and consume, but I think it is increasingly important to be an educated consumer who understands commodity chains, and where the products they use and consume come from. Seafood is especially important given the history humans have with over-exploiting resources and destroying the environment.

Commercial fishermen have depleted many stocks of commercially caught fish around the globe, either through mismanagement, greed, overexploitation, unenforced regulations or environmental degradation. Alaska is one of the last places on the planet huge commercial fisheries still co-exist with a mostly pristine environment and my goal is to highlight the best practices and pride Alaskan fishermen take not only in harvesting, but protecting the resource they utilize. Fishermen and the future of fisheries in Alaska and the world are dependent on sustainably managed fisheries and an unspoiled environment. Fishermen are increasingly becoming more aware and active in preserving their livelihoods by protecting the species they harvest and the environments they live in. My goal is to help tell the story of the fishermen, the fisheries, and the fish; and hopefully educate the viewer on who is harvesting the food on their plate and what it took to get those endless crab legs to Red Lobster.

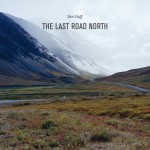

Your body of work A River Divided, which we’re showing here, seems a bit different than some of your other work. Can you speak to your approach on the Taku, and why you feel the work is important to be doing on your own?

My work on A River Divided really started when I was 18 when I first started commercial fishing on the Taku Inlet. This project allowed me to reconnect with my commercial fishing roots, tell the story of fishermen on both sides of the border, and educate people on the potential ills of an under-regulated mining industry and a regional government that has emphasized resource extraction and development, over preserving the environment to protect commercial fisheries and the people dependent on the resource for subsistence and cultural needs. It also allowed me to return to my journalistic roots of a straight documentary project. A lot of the commercial fisheries I document are for clients that are marketing either a specific fishery or the product the fishery produces. As a result that imagery has a tendency to be a little cleaner and less gritty than a strictly documentary project like A River Divided.

The Canadian fishermen who are fishing right up to the United States border before they pull their nets are straddling the line between two countries and on a river that has a history of mines like the Tulsequah Chief and Polaris and the age-old tale of destroying the habitat necessary for successful and healthy fisheries. I undertook the project by myself so that I wouldn’t be associated with a specific group and or influenced by the story they wanted to tell. Also it was helpful to not be directly associated with an environmental or non-governmental organization as some of the fishermen on the Canadian side of the river are conflicted about the development of the Tulsequah Chief mine with some either having worked for the mine or that have family members that did. In remote corners of the globe sources of income are largely derived from resource extraction, of which fishing is just one of many types, and I think the Canadian fishermen are very cognizant of this fact.

We hear a lot of talk these days about transboundary mining, especially with the Mount Polley spill last year. Does this threat to Alaskan waters feed, to some degree, A River Divided?

Absolutely, A River Divided is focused around the transboundary mining issue and the threat posed by remote Canadian mines that threaten some of the largest pristine salmon streams left in North America that flow across the border into Alaska. My work on the Taku River started in 2010, and the issue has only gained in awareness peaking with tragic Mount Polley spill. The state of the Tulsequah Chief and Mount Polley spill are very prescient of what will happen, and continue to happen, if the British Columbia government does not hold the mining industry to the highest standards in developing the proposed mines and having the foresight to not permit mines that cannot be mined in an environmentally responsible fashion. What it boils down to is that these mines will extract minerals and ore for 30-50 years, and the tailings will sit as ticking environmental time bombs for a minimum of a couple hundred years and up to a thousand or more.

The photographs that I captured of the acid mine drainage at the Tulsequah Chief mine site flowing into the Tulsequah River was only possible because the company attempting to develop the mine, Red Fern, went bankrupt and the mine went into forfeiture. I figured this would be my only option to get access to the mine site and document at the ground level the pollution flowing into the adjacent salmon spawning and rearing habitat. Despite the visual impact of the polluted water flowing from the mine, I felt the images rang a little hollow without telling the story of those directly affected on both sides of the border, hence the photographs of the fishermen on both sides of the border.

Will you be heading back to the Taku for pictures this year?

Unfortunately, I will not be heading back up the Taku this year as my summer is booked with commercial fishing in Bristol Bay and photography projects around Southeast, Alaska. At this point, I foresee the next trip up the Taku as a river float from the headwaters to further document the river, the environment, and wildlife that exists along the river. After that’s complete I would like to focus on one of the other transboundary river systems that have mines under development to help raise awareness on the issue and document the people and fisheries on both sides of the border.

Which came first, fishing or photography?

I bought my first camera at a State of Alaska surplus auction when I was 16 and have been shooting ever since. When I started fishing, I always had a camera aboard the boat, but I didn’t get serious about photographing commercial fishing until I started fishing in Bristol Bay in 2007. At that point, I had embraced the idea of trying to make it as a professional photographer and saw an opportunity to document the largest sockeye salmon fishery in the world. After a couple seasons photographing in Bristol Bay, it became increasingly apparent that I was creating a niche for myself photographing commercial fisheries. What started as personal projects, slowly morphed into editorial work and eventually commercial shoots for clients.

I’m often envious of you, as you have built photography, it would appear, so seamlessly into your life here – fishing in the summer and skiing in the winter. Can you see yourself living somewhere other than Juneau or Alaska? Would you still be drawn to photography someplace else?

I would love to say that it was a natural evolution to go from photographing fisheries in the spring, summer, and fall and winters shooting skiing and snowboarding. I honestly didn’t start snowboarding until I was 26, and I feel pretty fortunate that my group of friends is filled with some extremely talented skiers and riders, aka models. Chasing them around the mountain made me a better rider and allowed me to reconnect with shooting sports; something that I definitely missed from working at a newspaper.

As to living somewhere other than Juneau… I guess it just doesn’t seem fathomable at this point in my life. So much of who I am is intertwined with the place, the people and the environment; and after 32 years here, living somewhere else would mean constantly feeling homesick. I need mountains, water, and snow, and in all my travels I have yet to find a place that compares to Juneau. I feel very fortunate that either through hired work or personal projects I am able to photographically explore the world, whether it is shooting skiing in South America and Japan or photographing commercial fishermen in France. As exciting as it is to explore new places photographically, I am always filled with an overwhelming sense of comfort when I look out the window of the plane as it descends below the ever-present layer of clouds over the archipelago of Southeast, Alaska into Juneau.

How has living here shaped you?

Growing up in Alaska, and I think especially in Juneau, is in large part what fuels my desire to explore and photographically document the world around me. I recall at a very early age spending entire days in the rainforest behind my house. Each day brought a new adventure and opportunity to journey further into the woods, building forts, hunting deer, porcupines, and rabbits, and tracking signs, either real or imagined, of bears and wolves. I think in large part the exploration of my environment as a child helped to foster my imagination and ultimately fuel the creative vision that inspires my photography. I’d like to think that if I grew up in Washington or Oregon I would still appreciate the surrounding wilderness. The remote nature and ideals that surround the Alaskan experience are distinctly different than that of the Pacific Northwest and despite some commonalities Alaska remains unto itself.

Alaska and the opportunities it provides for work and play, often the two are intertwined, heavily shape the people who live here. Alaska is so vast geographically that it encompasses environments from the frigid Arctic, wet rainforests of the southeast, the seamlessly endless tundra of the southwest, to expansive boreal forests. Juneau is isolated from the rest of the world with no roads in or out, and this notion of isolation makes us appreciate our surroundings and take advantage of all they have to offer, because leaving requires a plane or ferry. It also fuels the desire to explore the periphery and further, but for me I find myself reinvigorated by the place and the people. I hope that my photography is creating at the very least a document of the place that helps to better define the Alaskan experience from within and not from that of reality television.

Do you feel that being part of a larger photographic community is important? What is your impression of the community in Alaska?

My photography is largely a solo endeavor documenting the exploits of those around me; as a result I at times identify more with my subjects than I do with other photographers, e.g. a fisherman who photographs or a snowboarder who takes pictures. My interactions with other photographers are limited to you, and the handful of professionals who live and work in Juneau. I very much miss the photographic culture and community that I had in college fostered by Stephen DiRado and Frank Armstrong. I still have a strong connection to the photographic community in Worcester and relish every opportunity I have to visit and sit around the table at one of Stephen’s salons.

The Alaska photographic community, from my perspective, is pretty diverse and extends to all photographic disciplines and genres. There is a large and very active group of amateur photographers in Juneau, and I am regularly impressed with how they reinterpret the heavily photographed areas, and wildlife found along the small Juneau road system. I have to admit it also fuels me to go further afield on the nights the northern lights are out, as there is rarely a turnout along the road that doesn’t have a tripod and LCD lit face. I am also extremely impressed with the photos in the Alaska Positive statewide-juried photographic exhibition, ranging from professional to amateur photographers that highlight the talent and depth of photographers in the state.

I am currently sipping on a beer in the Anchorage airport, waiting to catch a flight to Togiak, Alaska to document the sac roe herring fishery. Togiak is the furthest west fishing district in Bristol Bay and is the last major river system I have yet to document in the region as a part of my ongoing project photographing in the area. My fingers are crossed for nets full of fish, walrus, beluga whales, scale-covered fishermen, and further exploration of a familiar and yet foreign landscape.

I will spend my 9th summer commercial fishing and documenting the salmon fishery in Bristol Bay this year, and my second season posting images during the season to social media to share the experience of being a commercial fisherman in Bristol Bay. It requires a satellite modem, missing out on much-needed sleep, and some willing crewmembers to pull up the slack for me while I snap photos instead of picking fish.

I am also hoping to return to the Brittany region of France to continue documenting the fishermen there and hopefully see an exhibition of my commercial fishing work on display this summer in the Escales Photo Exhibition. After that, I will be dreaming of snow and just see where the winter takes me, possibly back to Japan…?

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Naohiro Maeda: Where the Wild Things AreDecember 26th, 2023

-

Adam Ottavi: The States Project: AlaskaMay 2nd, 2015

-

Ryota Kajita: The States Project: AlaskaMay 1st, 2015

-

Chris Miller: The States Project: AlaskaApril 30th, 2015

-

Brian Adams: The States Project: AlaskaApril 29th, 2015