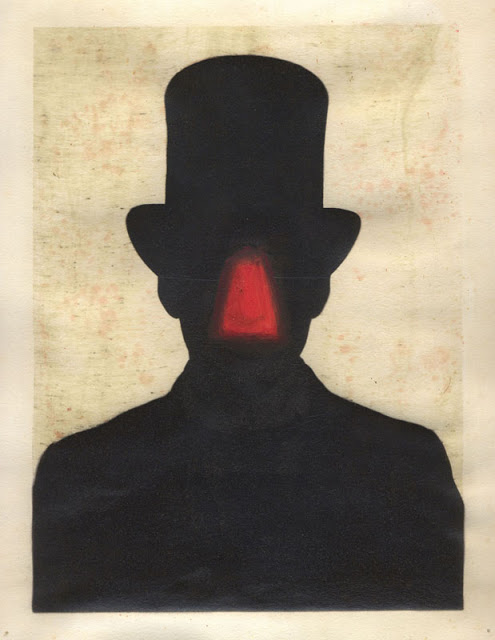

The Clown

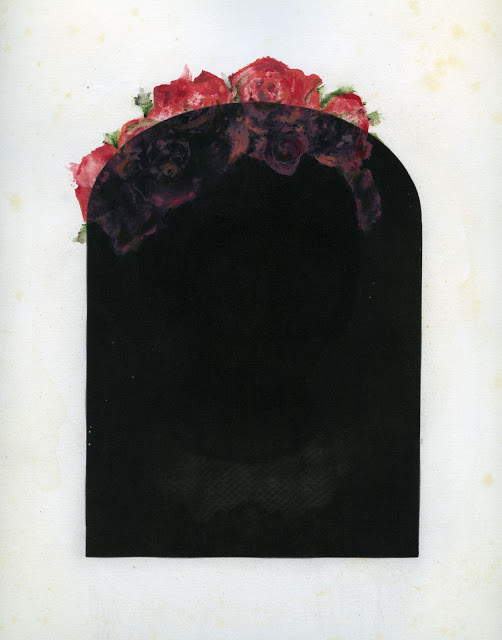

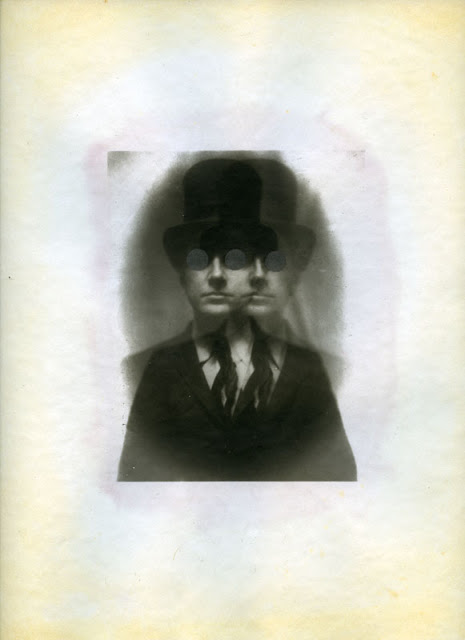

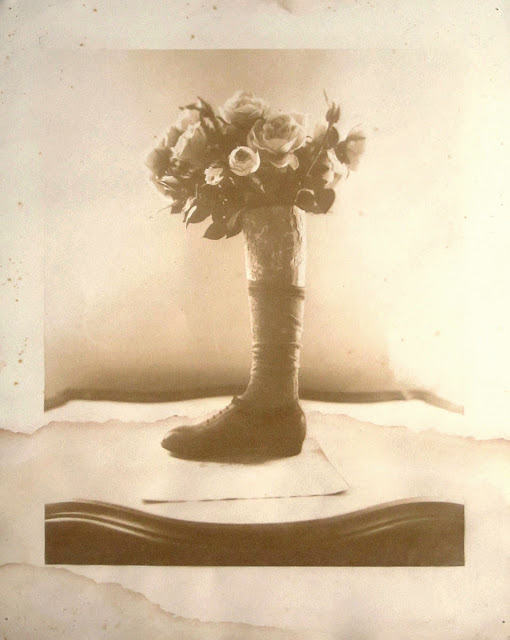

How best do we tell our stories? Our recollections may be based on events, milestones, or childhood photographs, but in reality, our personal histories are a series of visual remembrances–glimpses of what was and what might have been. Dan Estabrook has recently opened a terrific exhibition of personal storytelling at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in NYC, Our Song, in Twenty-Six Parts that is comprised of 13 new gum bichromate and carbon prints with applied paint intertwined with a selection of historical photographs and found objects. The exhibition runs through June 15th, 2013.

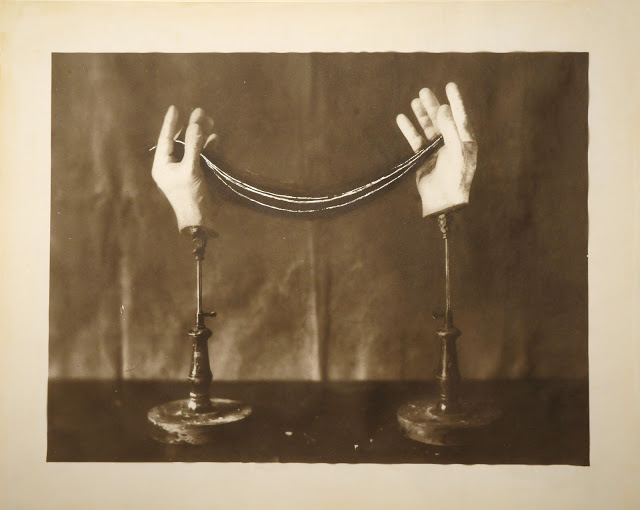

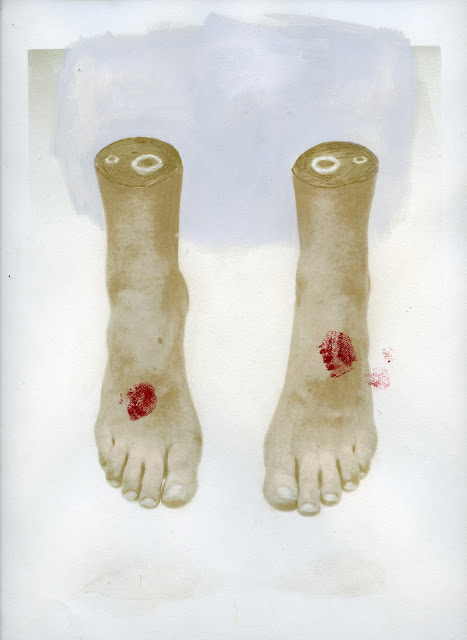

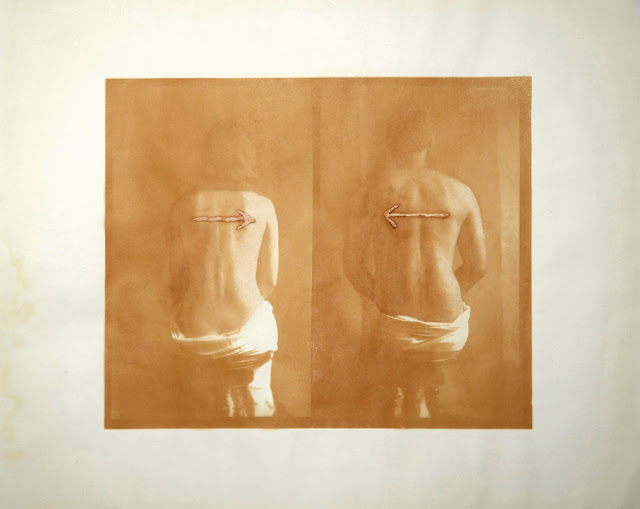

At the center of the exhibition sits Our Song made of a music box and paper with watercolor and pencil. The music box plays a repeated melody found in the stains of an old scrap of paper. On the walls are images made from antiquated photographic processes with applied paint and pencil markings. Along side Dan’s images are historical photographs such as an 1860’s tintype, which documents a medical procedure known as “blood letting”.

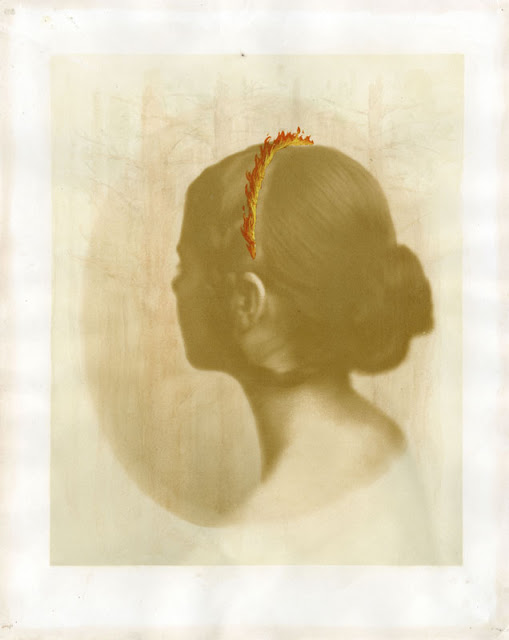

Small Fires

For over twenty years Dan has been making contemporary art using a variety of 19th-century photographic techniques. For some time he has focused on early paper processes – from calotype negatives and salted paper prints to gum bichromate and carbon prints – as sources for hand manipulation with paint and pencil. He balances his interests in photography with forays into sculpture, painting, drawing and other works on paper.

Dan has exhibited widely and has received several awards, including an Artist’s Fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts in 1994. He is also the subject of a recent documentary by Anthropy Arts. He is represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York and Jackson Fine Art in Atlanta. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

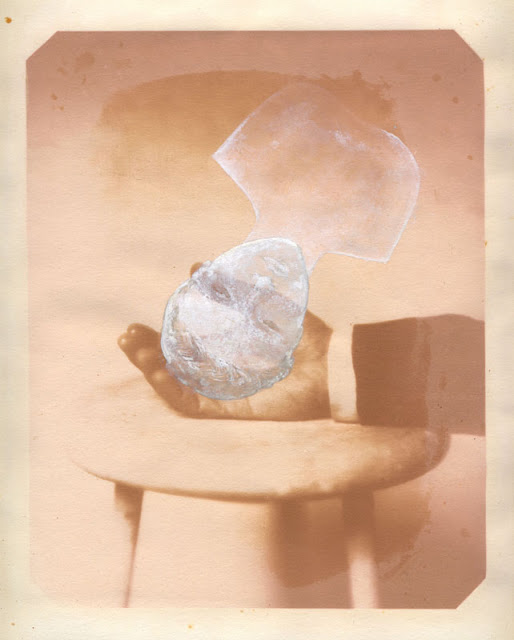

To Reach You, Too

Our Song, in Twenty-Six Parts

Every history is built of bits and pieces, an incomplete puzzle forming a picture just clear enough to see. With a few well-defined corners, a recognizable building, a credible chunk of sky, we figure we can fill in the rest. Any gaps and spaces still missing, well, certainly they only prove what we already know, don’t they?

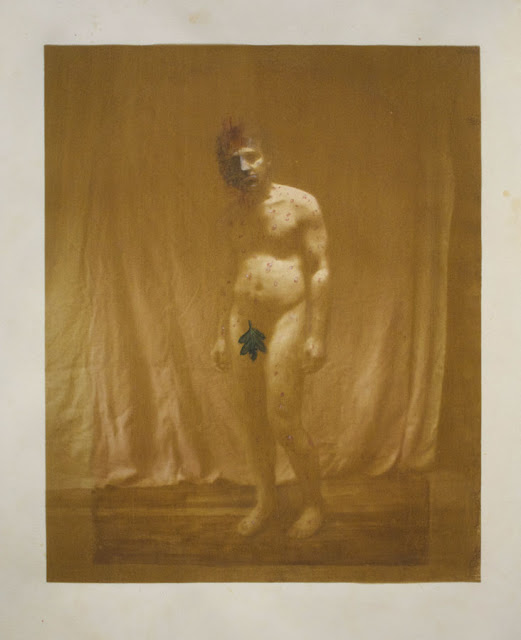

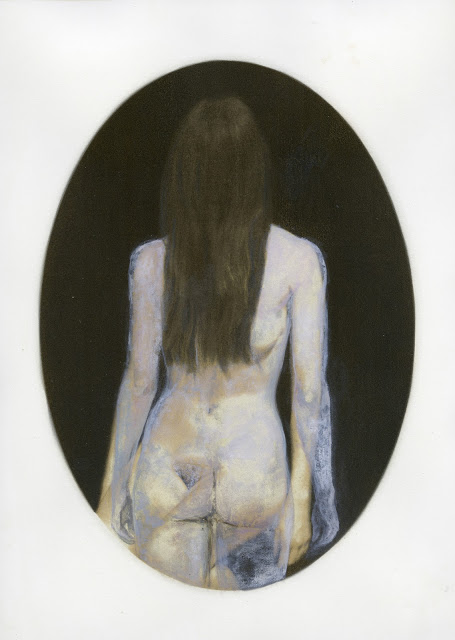

Our Song in Twenty-Six Parts is a personal history told in scraps and fragments, some found, some made. It is a love story of sorts, told over and over, embodied in relics and images from a parallel history of photography, one complicated by painting, drawing and other interventions on the image. Inspired in part by old medical photographs, it is not intended to revive some older and weirder time, but to use my own present point of view to tease out from the past the obsessions and desires – imagined or not – that match and justify mine.

A Head of Venus

There is a strange gut reaction to viewing old photographs, especially medical photographs – something truly visceral that I just don’t think happens with drawings or paintings. When looking at pictures of bodies, even parts of bodies, it is difficult not to identify, project, empathize, stare. I think, This body is my body (except when it’s yours…) To look at old photographs like these, or sometimes even ones that just look old, I wonder how these little objects could inspire such fear, such lust. After all, isn’t it just chemistry?

Alphebet

Dan would like to thank Dr. Stanley B. Burns, Peter Cohen, Emma Cline, Zac Lopez-Ibanez at the Penland School of Crafts, and the Frances Niederer Artist-in-Residence Program at Hollins University, where much of this work was made.

Harlequin

Notes on the processes:

A Gum Bichromate print is a nineteenth-century photographic process that contains watercolor or other pigments within the emulsion itself, yielding an image in any color. A mixture of pigment, gum arabic and light-sensitive dichromates is coated onto watercolor paper and exposed in contact with a negative. Any areas exposed to light harden and adhere to the surface; the unhardened pigment washes out. This can be done repeatedly on the same print, layer on top of layer. Since there is no silver or other fugitive metal within the emulsion, the Gum print was heralded for its permanence. Since the emulsion is quite soft and malleable as it washes out, this process was often used for its painterly effects, as by the artists of the Photo-Secessionist movement.

Back to Front

The Carbon print is in many ways an improvement on the Gum process. It, too, is made with a dichromated colloid, but usually of pigmented gelatin instead of gum arabic. By exposing one layer of colored gelatin on an intermediate “tissue”, and then transferring that image to the final surface for development, one creates a print with a much finer range of tones. Like Gum Bichromate, the Carbon process is quite permanent.

Before and After

Memoria

Brain Surgery

Stigmata

The Blind

Dermagraphs

The Boy