Marti Corn: Lost

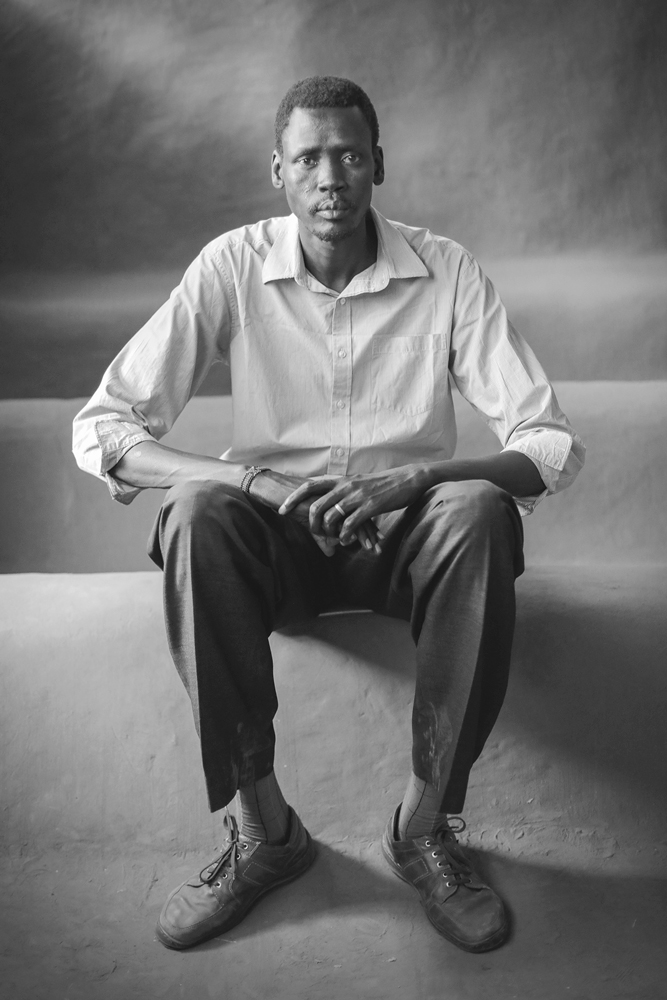

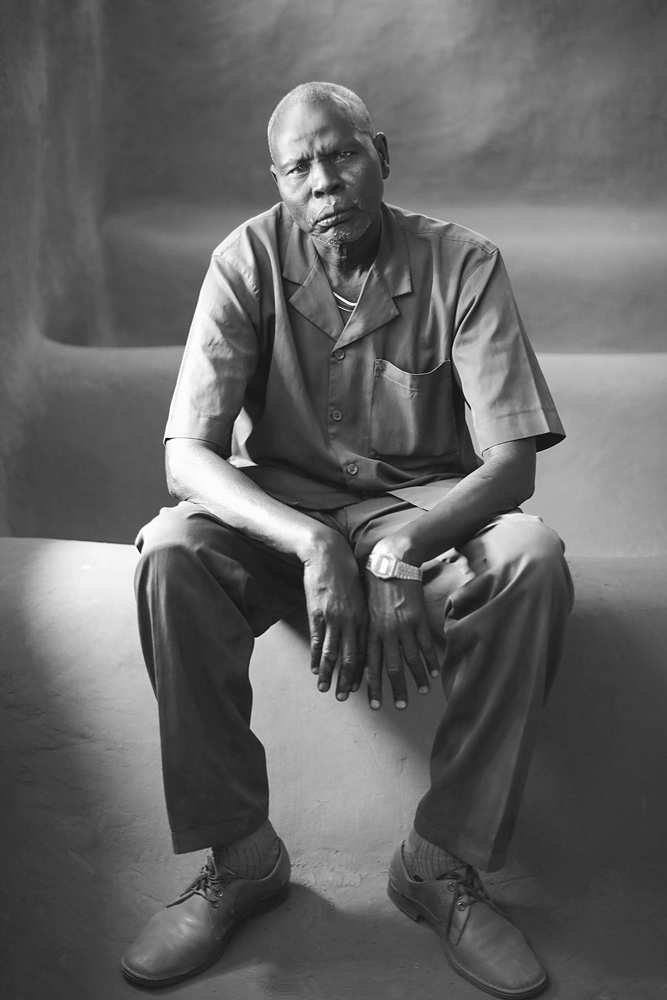

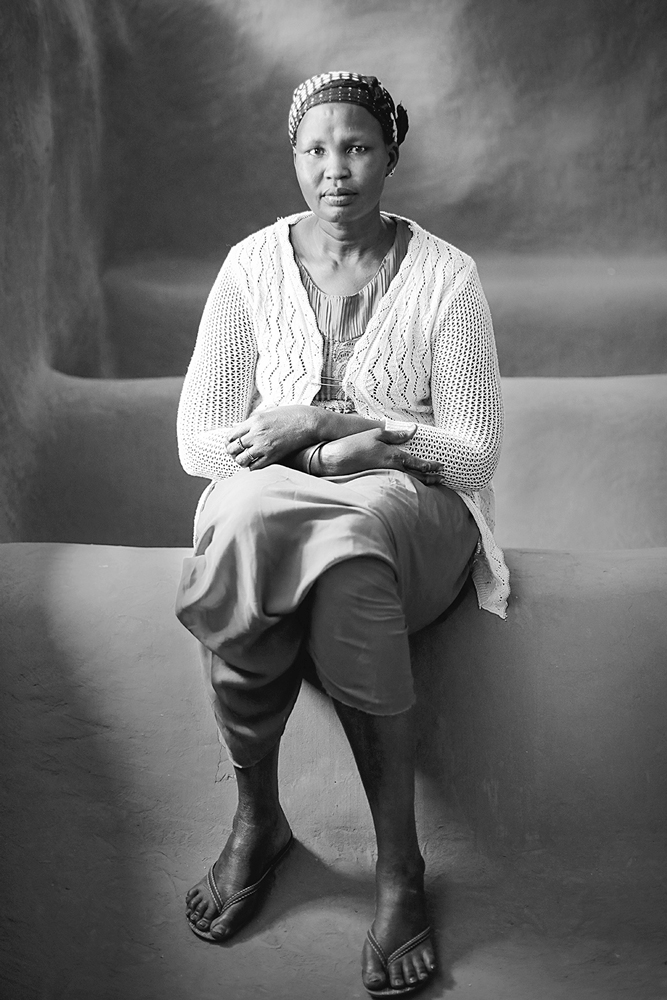

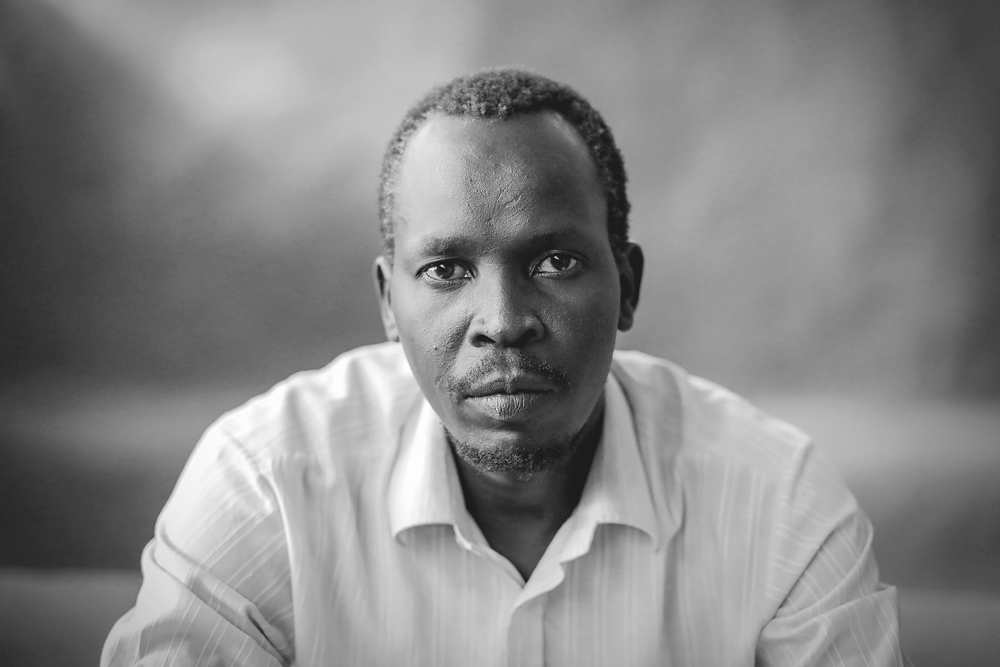

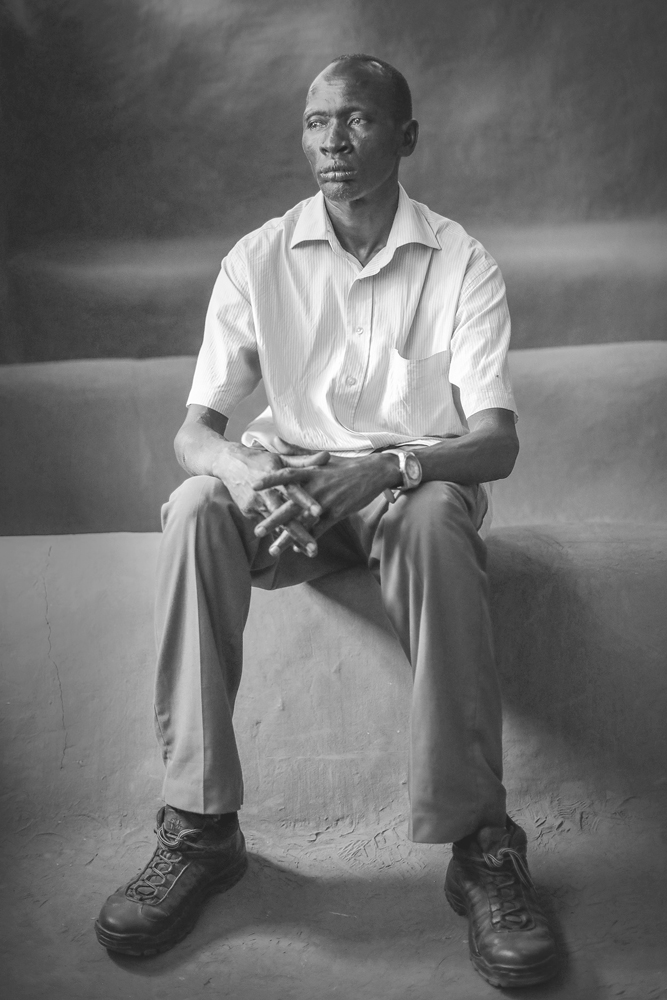

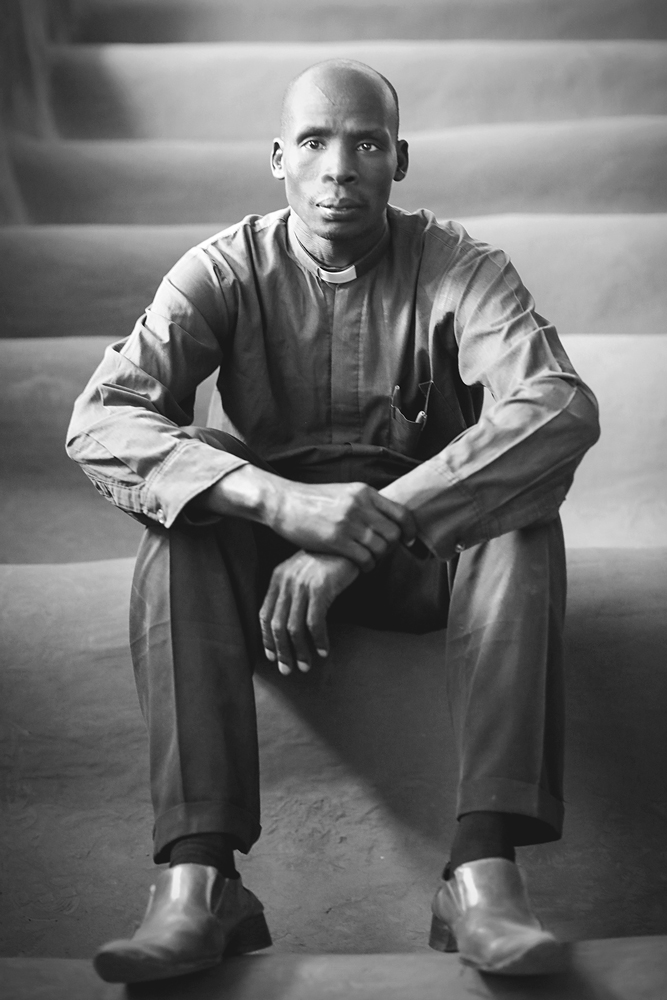

It was a pleasure to reconnect with Marti Corn at the Denver Portfolio Reviews and spend time with her compelling portraits of the Lost Boys of Sudan. Marti has a legacy of storytelling, in particular, focusing on peoples that are under served and overlooked. Her empathetic and connected approach to portraiture is revealed in her photographs. For her series, Lost, Marti has created a beautiful hand made book that allows for a celebration and honoring of her subjects. All profits from the book help the children of the Lost Boys with Education. The book is $3500 and can be purchased directly from Marti.

Marti Corn is a photographer and oral historian. Her projects revolve around social justice issues.Her first long-term project took place in Tamina, Texas, one of the few remaining emancipation communities in the United States. After gathering oral histories and making portraits of 12 families for four years, Rice University hosted her solo exhibit in 2014. A residency at Hilmsen near Salzwedel, Germany, gave her the time to edit this collection, which was published by Texas A&M Press in June 2016. One of these images was accepted into the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition and is on display in six museums, including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Museum of Fine Arts Houston and New Orleans’ Ogden Museum of Southern Art have acquired prints from this project for their permanent collections.

A Houston Arts Alliance Grant awarded in 2016 gave Marti the resources to document refugees who have become residents of Houston. Currently, her focus is on documenting the lives of those living in Kakuma, a refugee camp in Kenya.

Marti empowers those who have been oppressed, dismissed, or marginalized, by providing a safe space for them tell their story. In addition to her documentary work, she teaches workshops, sharing tools which allow them to take some control over how they interact with their world. Also, she has helped a group of young journalists in Kakuma establish their own studio, enabling them to become self-sufficient while also providing community outreach programs, including teaching photography in area schools.

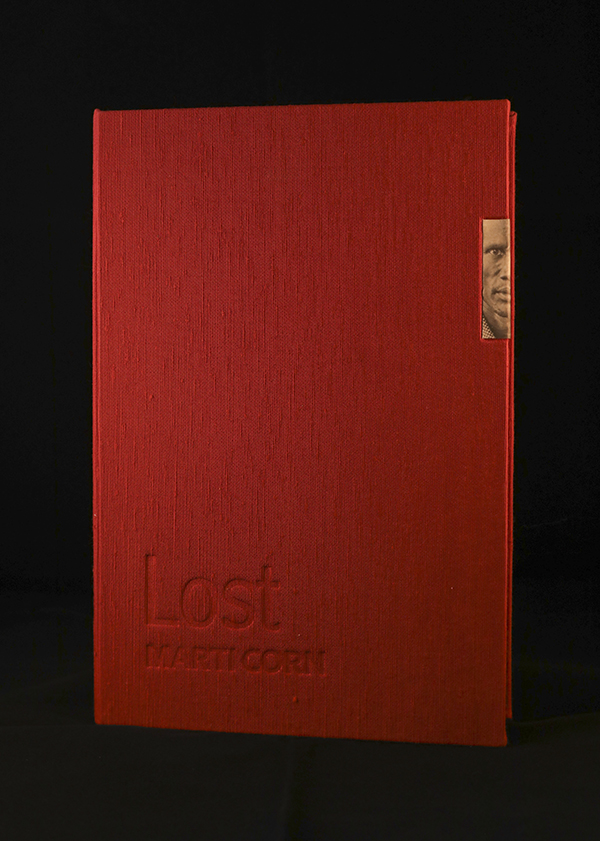

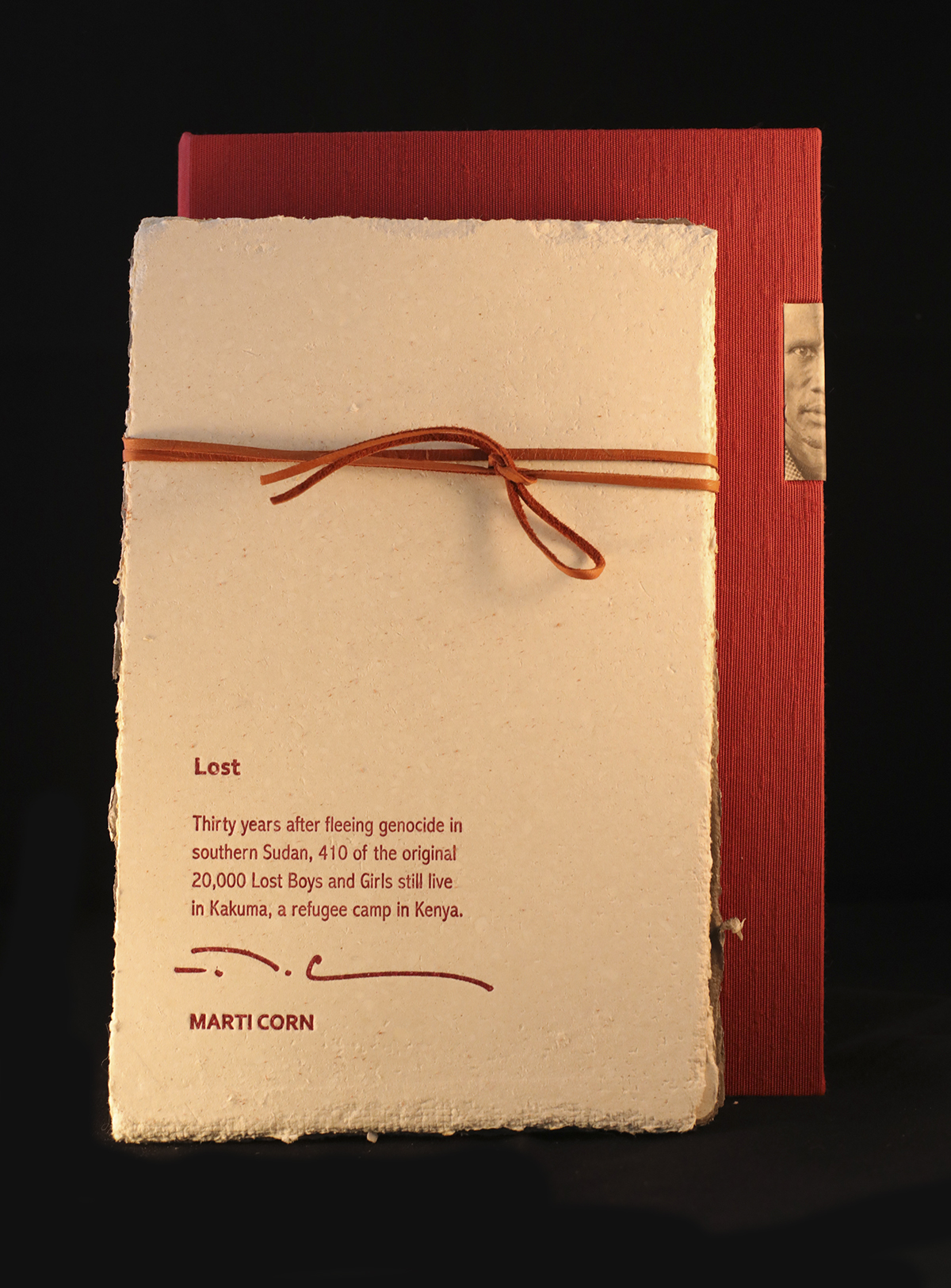

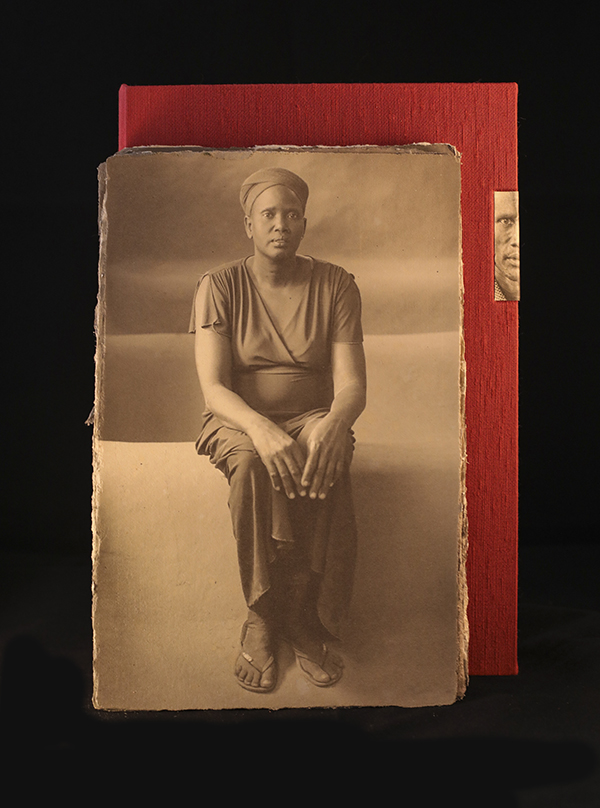

Lost – A Limited Edition Collection Held Inside a Custom-made Clamshell Box

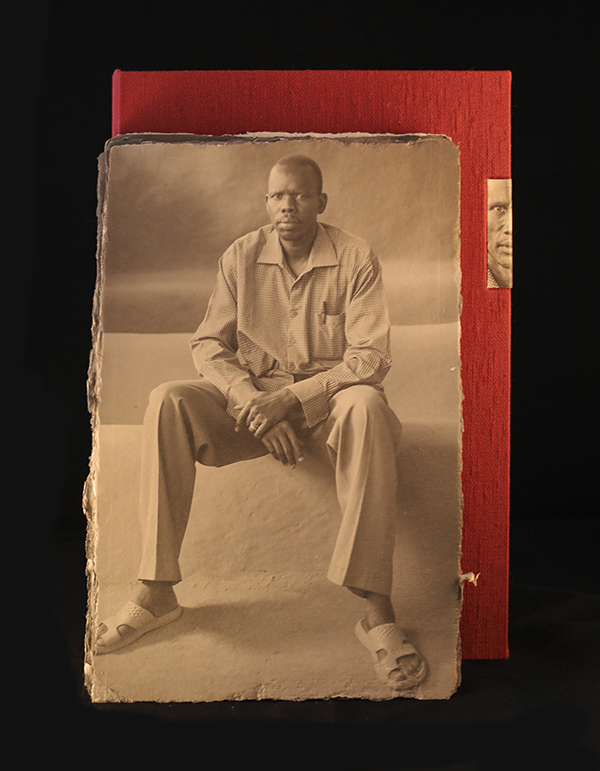

Tethered in a strip of leather, 12 portraits printed on unique handmade paper, along with an introduction and essay written by the artist printed on a letterpress, are cradled in a custom-made clamshell box make this limited collection.

Copies of the Lost Boys and Girls’ most guarded possession—their manifest, which is their documentation containing their family members’ names and photos, identification numbers, and ration card numbers—were used to make the handmade paper for this collection. The paper was toned with coffee harvested in Ethiopia and roasted in Kakuma as well as Kenyan dirt from the South Sudanese church where the portraits were made.

All profits help provide the children of these Lost Boys and Girls with education. The sale of each edition will provide school fees, uniforms, paper, and pencils for 20 of the children of Kakuma.

Lost

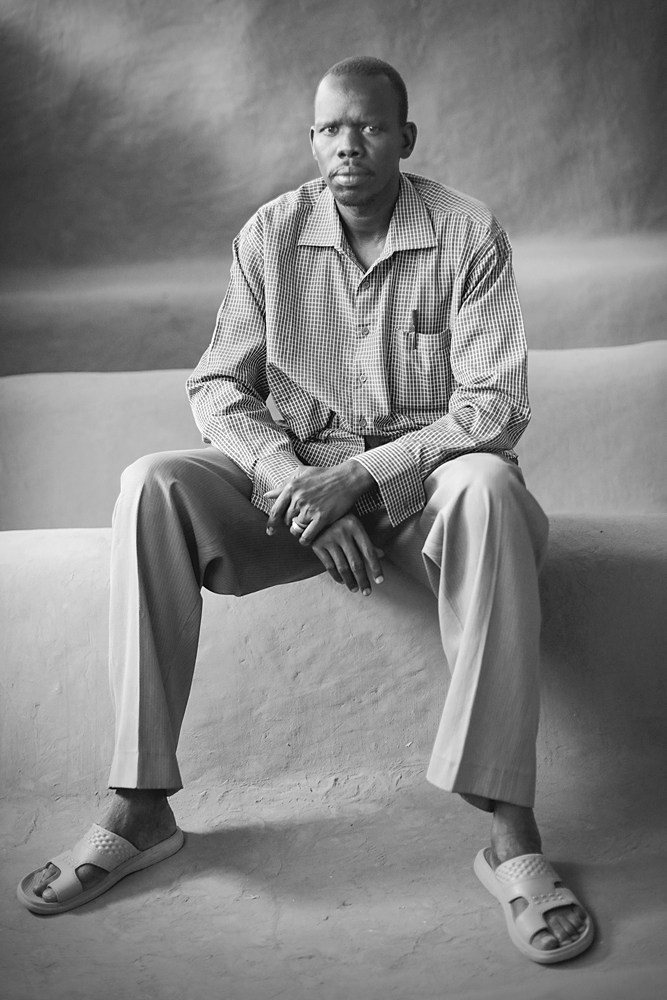

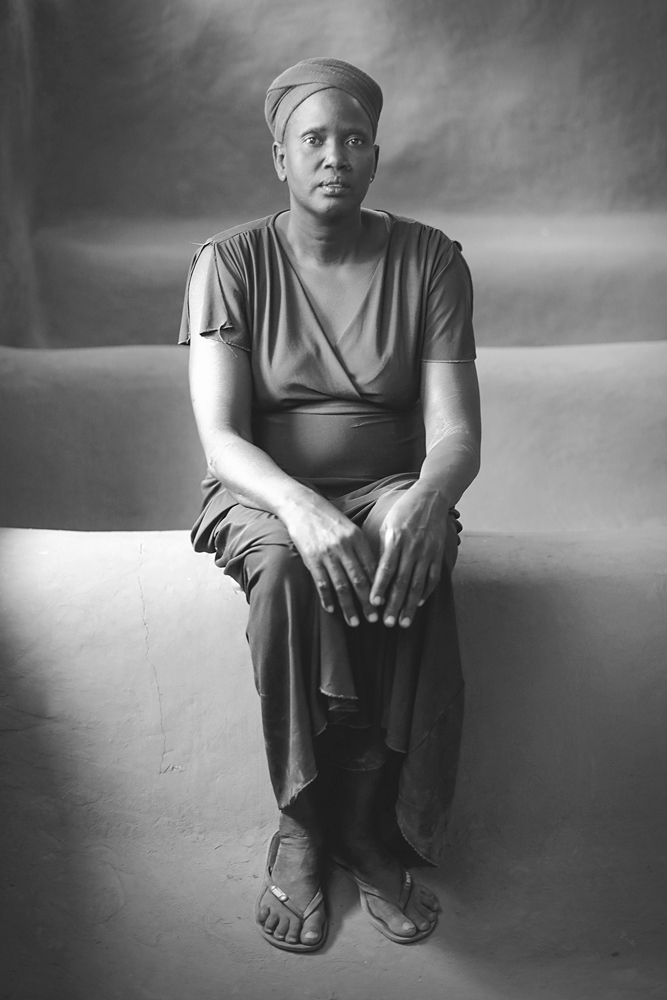

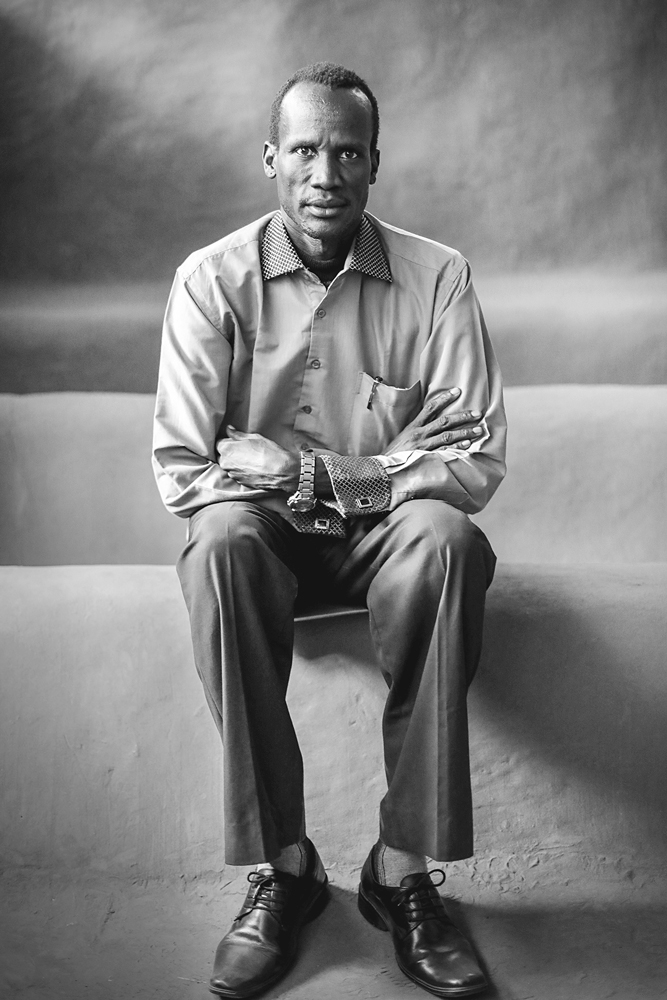

The Lost Boys of Sudan is a familiar story. Escaping genocide in 1987, 20,000 displaced and orphaned children fled to Ethiopia and then, four years later, to Kakuma, a refugee camp in Kenya. Half died due to starvation, exposure, drowning, attacks by wild animals, and ambushes by fighting forces. Because of media exposure, many were resettled in the U.S. in 2001. Others returned home to join the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). I’m documenting those who were left behind.

According to the elders within this South Sudanese community, 410 remain in Kakuma, thirty years since their perilous journey.

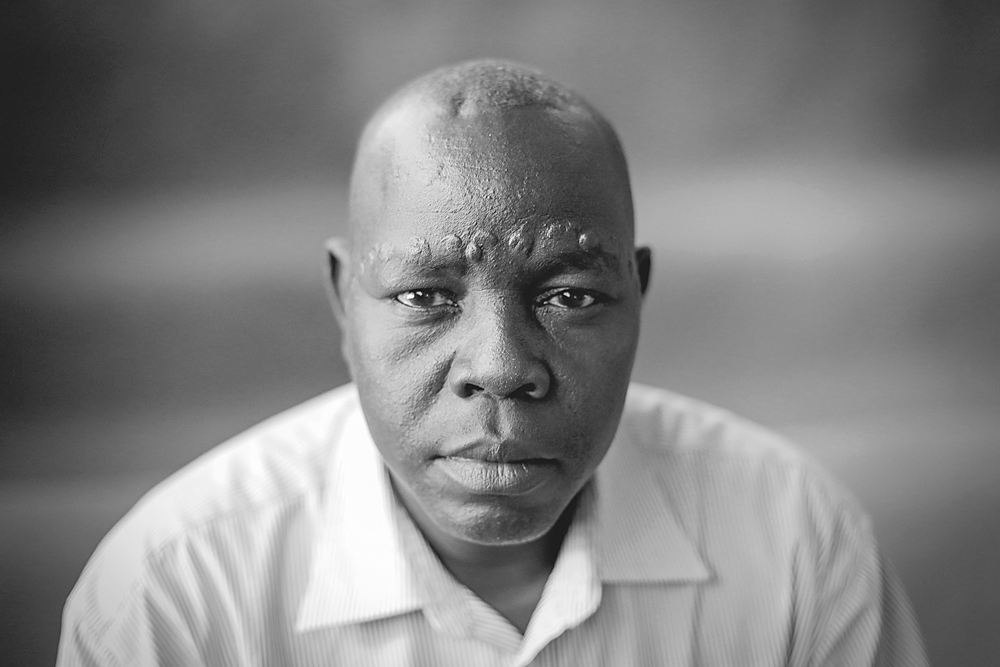

I travel to Kakuma twice yearly, making portraits and listening to the stories of the remaining Lost Boys and the rarely mentioned Lost Girls, as well as their caretakers. I sit inside their makeshift church as they share their memories of that thousand-mile journey. They describe the misery of living in a place they’re not allowed to call home, become citizens, or the dignity of self-sufficiency. Surprisingly, they also express their continued hope that one day they and their children will have a chance for a better life. Then, in silence, they patiently sit on the dirt pews with light streaming in from the carved-out windows as I make their portraits.

This project provides an intimate look at a community of refugees who have lived much of their childhood and their entire adult lives within a refugee camp. While the story of the Lost Boys of Sudan is widely known, there’s no documentation of those who remain. Their suffering, as well as their enduring hope, can help us gain insight into an ever-growing world-wide crisis. Perhaps we can learn how to better understand the ill-effects of this current system and even provide a window of understanding how mankind can remain hopeful, even when they’ve been betrayed by humanity.

The Sudanese

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026