South Africa Week: Jabulani Dhlamini

The events of the Sharpeville Massacre marked a turning point in the history of South Africa and galvanized opposition against the apartheid system. On March 21st, 1960 thousands of black residents presented themselves at the local police station in the Sharpeville township and offered themselves up for arrest for not carrying their passbooks — an identification document issued by the apartheid government. The police quickly issued an armed response against the protesters, leaving sixty-nine people dead and 180 injured. Outrage at police actions prompted protest marches around the country and transformed the political response towards the apartheid government by opposition groups from passive to armed resistance.

The events of the Sharpeville Massacre are etched in the minds of many South Africans through documentary images of women and children running from police fire and armed vehicles. Iconic photographs, such as ones taken by Peter Magubane, Ian Berry, and G. R. Naidoo in the township, form the basis of the nation’s collective memory of the traumatic events. For many South Africans the black and white views of lines of coffins and wounded protesters being carried to safety went beyond a documentation of the events of Sharpeville and symbolized the pain of a systematically oppressed community across the country in the early days of the resistance.

Jabulani Dhlamini’s most recent series, Sharpeville, Recaptured, returns viewers to the rural township over fifty years after the seminal events occurred. Through a collection of landscape images, photographs of personal objects connected to the massacre, and buildings Dhlamini explores the lingering trauma of the fateful day. Dhlamini began photographing in Sharpeville in 2009 while a student at the Vaal University of Technology and developed his project in response to his interactions with residents who would tell him stories about how they or their relatives were affected by the massacre. In Dhlamini’ view these first-person narratives are notably absent from dialog and historical accounts of the shootings. “We keep on hearing this story about Sharpeville as a collective, but we have never given the chance to individuals to tell their stories, to share their experiences of the day,” he says.

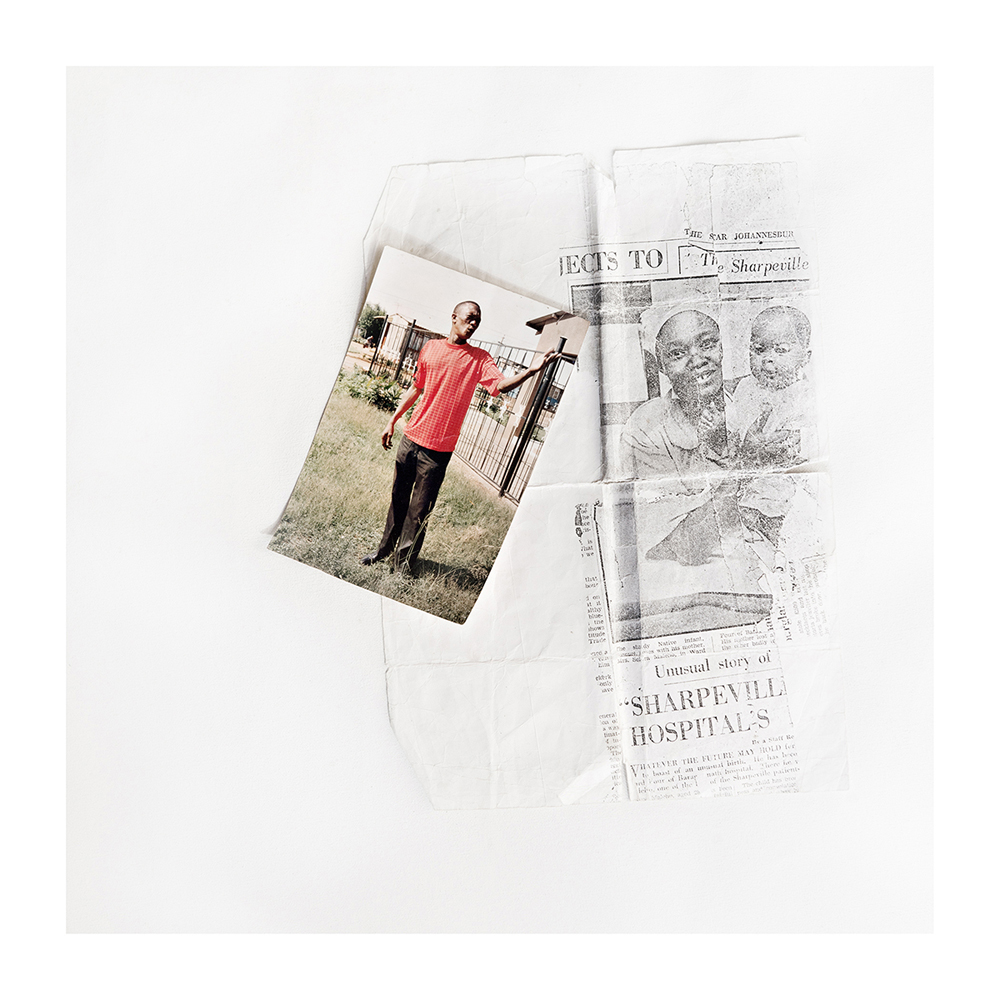

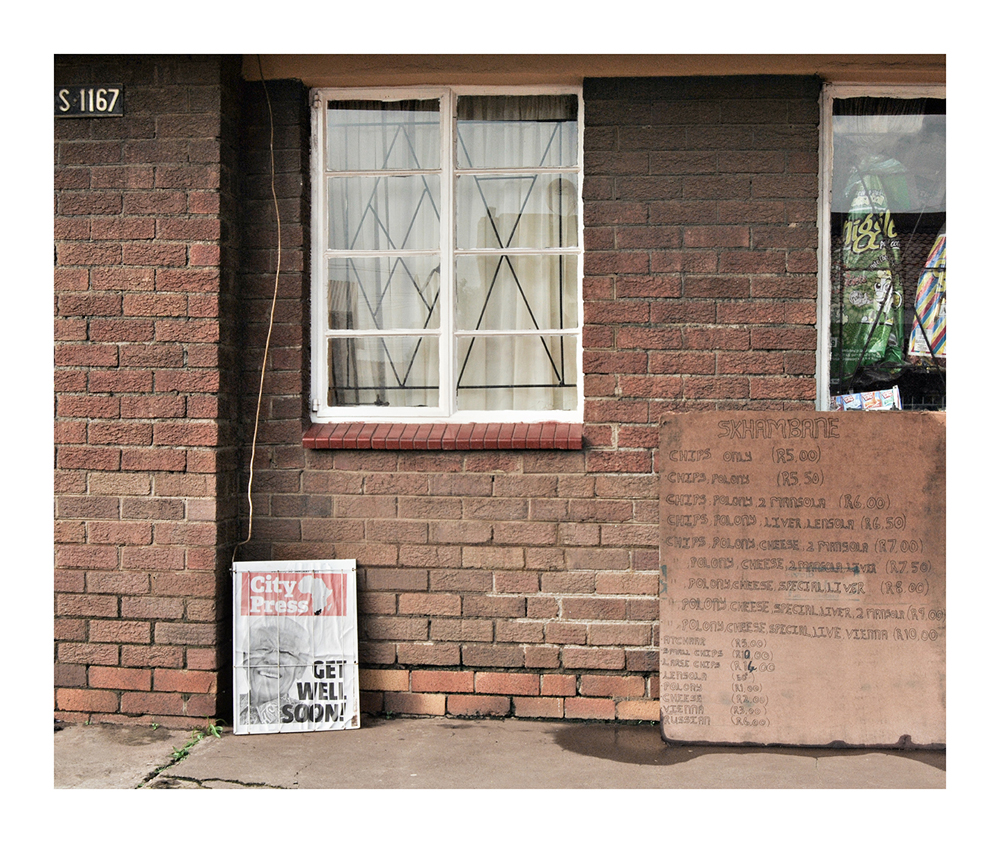

The Recaptured series recovers individual accounts and weaves them together into a web of survivor experiences. Images of nondescript buildings reveal places where individuals fled from police and sheltered from gunfire; landscape photographs of cemeteries and streets reflect on fallen kin, and exterior views of the old police station recall the first-person views of the initial conflict. Dhlamini’s landscapes are shown without people, an omission that challenges viewers to see the contemporary photographs as preserves of memory that remain in dialog with the past. These images are complemented by Dhlamini’s “self-portrait” photographs taken after completing an interview with a survivor. While processing an individual narrative Dhalmini would walk around the township and create images that could represent his personal feelings. A painted wall with faded graffiti and vibrant red forms recalls the immediacy and potency of the accounts that remains even as layers build on the visible surface. The self-portraits gave Dhlamini a means to reflect on the inherited trauma of events like Sharpville and the forms in which such trauma is passed down to new generations. Photographs of individual objects further build the series as an archive of inherited trauma. During his time in the township individuals would bring Dhlamini artefacts associated with the massacre: clothing worn by survivors, photographs of lost family members, and objects held or touched when gunfire started. Dhlamini pairs these images with excerpts from his interviews that both explain the item’s importance and insert individual voices into the series.

The Recaptured project seeks to broaden collective understanding of a traumatic but pivotal moment in the struggle against apartheid, but the series also represents the artist’s personal journey to learn about the resistance. Born in 1983 Dhlamini recalls aspects of events that took place in the waning days of apartheid rule: “I was five years six years in the dying times of apartheid and most of the things that were happening didn’t make sense to me…I remember people were singing, people not going to work.” Through his interviews with Sharpeville survivors and time photographing in the community Dhlamini seeks to build his own memories of the traumas of the past. “With this project I was trying to back-up my memory,” he says, and “even though I haven’t yet got where I want to go, I‘m still going somewhere where I can gain a proper understanding.”

Jabulani Dhlamini was born in Warden, Free State in 1983 and currently lives and works in Johannesburg. In 2009 he completed a diploma in Photography at the Vaal University of Technology, majoring in visual communication and theory of photography. Dhlamini also studied at the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg where he was awarded a 2011/12 Edward Ruiz Mentorship. This award supported the production of his first major body of work, uMama, which explores the experience of single mothers living in South African townships. Dhlamini has won numerous awards in photography, including two Profoto Awards in 2008 and 2009, a Fujifilm Southern African Photographic Award in 2009, and honorable mentions in the 2010 Photo Imaging Education Association Awards and in the 2011 Ernest Cole Awards. He has participated in exhibitions, including the Month of Photography in 2008 and Bonani Africa in 2010. Dhlamini also currently works as a mentor and organizer of the “Of Soul and Joy” project, a visual platform and a skills development programme based in Thokoza that offers photography workshops and mentorship opportunities for local students. Dhlamini is currently represented by the Goodman Gallery.

Sharpeville, Recaptured

“Recpatured” explores the results of my engagement, since 2008, with the residents of Sharpeville, reflecting on the massacre that took place there on March 21, 1960 as a turning point in South African history. On that day, without warning, South African police shot into a crowd of about 5,000 unarmed anti-pass protesters at Sharpeville, an African township of Vereeniging, south of Johannesburg. The massacre took the lives of at least 69 people – many of them shot in the back – and wounding more than 200 people. My series is created with an aim to reflect the individuality of eyewitnesses, and the survivors of the Sharpeville massacre, as they engage with the memories evoked by space and objects. It also affords them an opportunity to narrate their own story and experience.

My project revisits this dark day in a way that to date has been somewhat overlooked – through the intimacy of personal encounter and the objects that are emblematic of this. Although there is a memorial site, there is yet to be a museum dedicated to the memory of those who were shot dead, or survived, traumatised by the experience of being violently attacked for demanding basic human rights. The documentaries that have focused on the subject of the Sharpeville massacre often sideline personal engagement, in favour of cold historical record. In an attempt to process the massacre for myself, I have not only photographed places and objects of trauma – for example the back of the shop where people hid during the attacks or a pillow case concealing incriminating documents that formed part of the struggle against the apartheid state – but I have also set up a makeshift studio in Sharpeville, where I invited people to bring objects they associate with the day of the massacre. I photograph these objects, as long as the people who they belong to can contextualize them with the story about their connection to the massacre. – Jabulani Dhlamini

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 1st Place Student Prize Winner: Mosfiqur Rahman JohanJuly 22nd, 2024

-

Ellen Mahaffy: A Life UndoneJuly 4th, 2024

-

Julianne Clark: After MaxineJuly 3rd, 2024

-

Kaitlyn Jo Smith: Super8 (1967-87, 2017), 2017June 30th, 2024

-

Katie Prock: Yesterday We Were GirlsJune 27th, 2024