Exhibition: From Ansel Adams to Infinity at the Chrysler Museum

Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, California, 1960, printed 1980. Photograph by Ansel Adams. Chrysler Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. T. Lane Stokes, 82.128. ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Now on view at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia, From Ansel Adams to Infinity presents photographs by Ansel Adams and contemporary photographers who were inspired by his work.

The exhibition commemorates the gift of a special “Museum Set” — a portfolio of 25 photographs printed by Adams himself. Toward the end of his seven-decade career, Adams began focusing on his artistic legacy, writing an autobiography and issuing portfolios of his most famous and technically accomplished works. The Chrysler Museum’s portfolio was acquired by the Stokes family of Hampton Roads who worked with Adams to select the works printed for the portfolio. The Chrysler’s exhibition includes 25 works that cover the range of Adams’ career and highlight several locations, including Yosemite, the Sierra Nevada, the San Francisco Bay and the Colorado Plateau.

The exhibition also highlights works by Abelardo Morell, Matthew Brandt, David Benjamin Sherry, Christa Blackwood, David Emitt Adams, Penelope Umbrico, Florian Maier-Aichen and Millee Tibbs.

I sat down with Seth Feman, Curator of Exhibitions and Curator of Photography at the Chrysler, to talk about Adams’ work, its relevancy today, and the future of landscape photography.

Eagle Peak and Middle Brother, Winter, Yosemite National Park, California, ca. 1968, printed 1980. Photograph by Ansel Adams. Chrysler Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. T. Lane Stokes, 83.633.3. ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Megan Ross: Can you give us an overview of the images included in the Museum Set?

Seth Feman: When it comes to Museum Sets, there are two sizes. There’s the 75-image set, typically printed by Adams’ assistants, and there’s the 25-image set that was printed by Adams. We have one of the 25 sets, all printed by Adams himself. There’s not much paperwork, but we do have a sense that the collectors — the Stokes family from this region of Virginia — went back and forth with the gallery about which images they wanted. The earliest negative is from 1921, and the latest is 1968. The big concentration is in the 1940s, from around World War II.

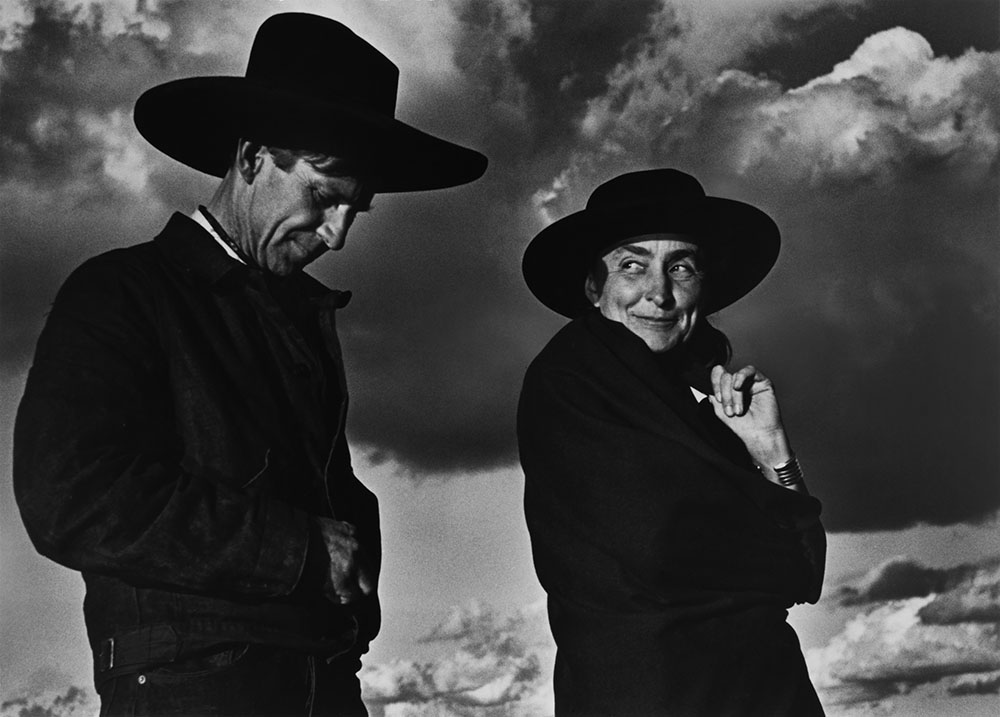

MR: As soon as I walked in, I was struck by the opening image – not one of Adams’ famous landscapes, but a charming photograph of Georgia O’Keefe smiling at Orville Cox. Why lead with this?

SF: I love this one. It stands out in the show for a number of reasons. It’s one of only two that has figures in it. And it’s also the only one [by Adams] that’s 35 millimeter in the show. You are reminded that Adams was making images in a lot of ways, sometimes a lot more casually than the formal work that we know.

But what’s striking to me is that it hits all of Adams’ photographic marks. He found a way to get a full range of tones. He’s heavily worked it — you can see the light halo around the people, and you can tell that he’s been working on the image to get them to “pop.” The darks are super dark, like in the hats and the clothes. And you get all these tones in between. It’s also a perfect introduction to the show because it suggests how mood can be conveyed through photography. It’s not just a document… it’s to say, “we were there and we did this together,” and there’s clearly a connection between them that they had when they were on this expedition together.

Georgia O’Keeffe and Orville Cox, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona, 1937, printed 1980. Photograph by Ansel Adams. Chrysler Museum of Art, gift of Selina and Tom Stokes, 2017.33. ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

MR: In 2014, Lenscratch covered a similar exhibition at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego. Next month, The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston will present “Ansel Adams in Our Time.” Why does Ansel Adams continue to be such a hot ticket for museums?

SF: What prompted this particular show was the completion of the gift of the Museum Set. The images started coming in the 1980s, but the last one arrived last year. The day it came in, I made a promise that as soon as we had time on the calendar, we would have an Adams show.

But besides that, there are a lot of good reasons to have an Adams show—in addition to the fact that he’s an extraordinary artist and we can learn a lot from him. People really love him. The response to this show has been extraordinary, in part because Adams is such a recognizable name. People know him and really appreciate the work. So there’s always a good interest in Adams, which is always good for us, because we want to invite people in and provide shows that engage our local audiences.

But I wonder — and this is totally hypothetical — if part of the interest in Adams is also contemporary. Many of us are thinking about the environment in very serious ways, and the politics of the environment. Here in this part of Virginia, we’re in a problem area that is facing rising sea levels and sinking land, and a lot of other environmental issues in this region alone. So at the Chrysler, we’re often looking for shows that can allow us to talk about the environment. Adam’s work is an easy invitation to think about a difficult issue. And I think probably other institutions are also curious about having that conversation because it’s on everyone’s mind.

I also think some of the contemporary artists in the show enable us to push the issue a little bit further. So it’s nice to have a balance between what’s welcoming and familiar, then there’s some really new and challenging ideas all in one show.

MR: And combining Adams’ work with the contemporary artists keeps it relevant.

Yes, it really sharpens the historical issues, and the historical issues really open up the contemporary work. They really do go hand in hand. It’s one thing to plan a show where you have historical work and contemporary work — it’s something curators do all the time — but here I feel like the conversation happening across the show’s installation is an active one. It allows each moment to grow and appear more vivid. I think it’s really fruitful in this example in particular.

Installation view, From Ansel Adams to Infinity at the Chrysler Museum. Photo by Megan Ross.

MR: Were there any surprises in the Museum set? Did you learn anything new?

SF: Mostly it was the stories that go with the photographs. I know Adams’ work pretty well, but I hadn’t done individual object research for a lot of the ones in the set. Understanding the context and the history of the image was interesting.

For example, one of the images [Snake River and the Grand Tetons] is included in the Golden Record, which is onboard the Voyager spacecraft. The same image was also intended for a mural that was commissioned by the National Park Service for the Interior Department building in Washington, D.C. that was never realized.

That got me thinking. Over Adams’ long career, his relationship with the federal government went through different stages. I knew about the days when Roosevelt Administration was interested in his work, and supported Adams’ message of American places and the value of conservation. But I didn’t know that toward the end of his life, he did a two year letter writing campaign to Ronald Reagan protesting environmental policy — mostly surrounding the appointment of James Watt, who was Secretary of the Interior and wanted to open up protected lands to mining and drilling.

It was interesting to see Adams working through the political side of things, and that’s been something I’ve enjoyed talking to visitors about on tours. The images are so beautiful, right? But they were also serving a political purpose.

We sometimes take Adams’ images for granted because we’ve seen them a lot. But this exhibition reminds us that Adams was an innovator. He was really pushing the medium to its limits and beyond. Many of the contemporary artists in the show are also involved in conservation work, so it ties in really nicely with what Adams was doing.

Installation view of Range: of Masters of Photography by Penelope Umbrico. Photo by Megan Ross.

MR: Can you talk about the contemporary artists included in the show, and what drew you to their work?

SF: In most cases there’s a direct acknowledgement of Adams on some level. And that’s not true with all them per se. Someone like Penelope Umbrico isn’t exclusively looking at Adams, but she’s certainly acknowledging Adams and other artists of that moment as her source material. I wanted those connections to be clear. I didn’t just want landscape — I wanted to make sure there was a kind of “Adams presence” in them.

Abelardo Morell’s piece is a good example. Something of interest to Morell is how Adams often spoke about the importance of capturing the experience of being there in his works. But although Adams’ images are beautiful, they can feel remote. What better way to connect you than where you’re standing? Morell created this tent camera that the images come through in a kind of periscope and he’s made a camera obscura – so he’s shooting down at the ground. You look at it and you know that something’s not quite right, and you have to puzzle it apart. And then you realize what’s going on and it’s a kind of a-ha moment.

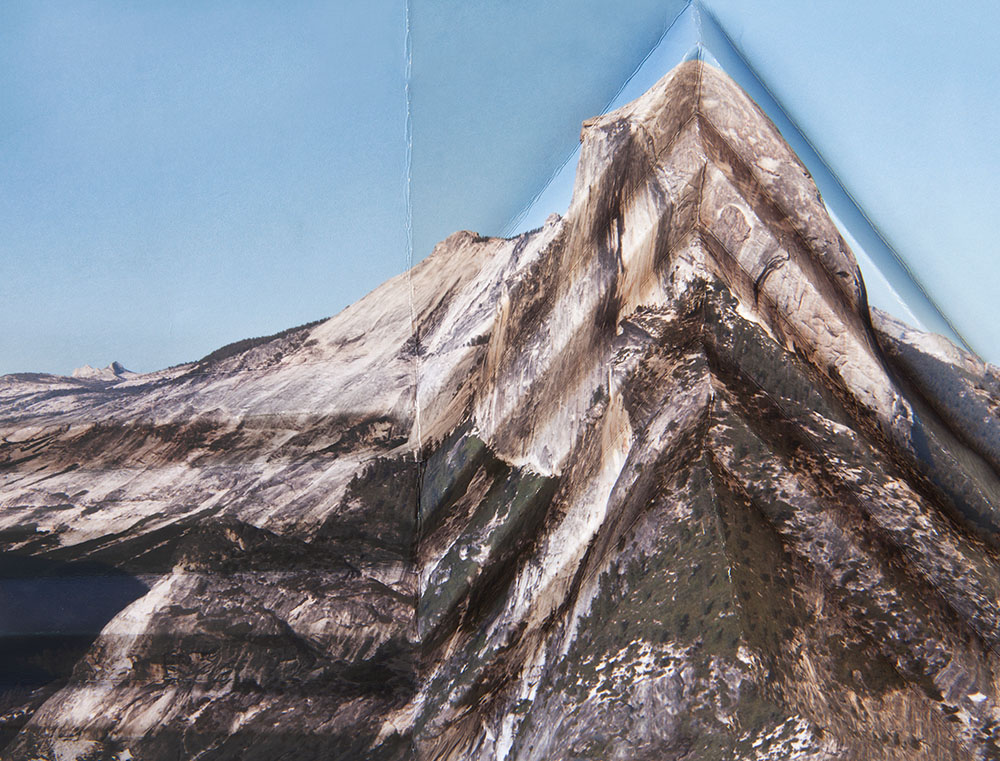

Millee Tibbs did a whole series called Mountains and Valleys, which are the names of oragami folds. She went to each site [including sites Adams photographed] and made her own photographs, printed them, folded them and rephotographed them. So you’re looking at a print of a photograph made of a folded piece of paper. What I like is that she at once enhances the illusion and destroys it. She’s built up the angle of the peak, so you get this sense of the physicality of the mountain. At the same time, she’s completely undermined it by ruining the illusionistic surface of the page itself. So much so that you can see that the emulsion is cracked from where she’s folded it. To line up the photo she had to destroy the perfection of the image. I think it’s fascinating.

There’s a type of feminist critique as well, that this production of landscape is very hands on. When you see something like this, you’re immediately reminded of the way the body is involved when making an image.

Millee Tibbs (American, b. 1976). Yosemite National Park #4, 2013, from Mountains + Valleys Archival digital print. Courtesy of the artist and Uprise Art, New York.

MR: How would you respond to critics who imply that landscape photography is dead; that it’s all been done before?

SF: I think that every time someone says landscape photography has been exhausted, it’s is an opportunity to prove them wrong. As you see in this show, there are a number of works that are really pushing into new territory. What’s really striking is the David Benjamin Sherry piece, for example [Holy Holy]. It’s a photograph of the landscape when it comes down to it — and yet, it’s totally new. It’s totally fresh. While one might say, “Adams took pictures of rock faces almost 100 years ago, how could this be different?” But what impresses me so much about David’s work is that it really excites you about looking. You really want to look more, which is part of the point of the work. It’s that invitation to look closely and even intimately with the landscape and I think that is something new.

Yes, it’s still the land, but the land is changing. And that’s really an Adams idea in itself. Adams was insistent about the land not being timeless, but that photographs present it at a moment — a feeling at a moment. I think if that’s true then new photographs of the land can always be pushing in a new direction. I hope people will come and see that there are some new innovations in landscape photography.

Abelardo Morell (Cuban, b. 1948). Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Rio Grande Looking Southeast Near Santa Elena Canyon, Texas, 2011. Archival digital print. © Abelardo Morell, Courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

MR: How do you want people to feel when they leave this exhibition?

SF: I think that when you see Adams’ work, you immediately start to think about your relationship to the land and that’s something Adams was after. It wasn’t just a picture of a place, it was conveying an experience in that place. I think there’s real opportunity to get people interested in the natural environment and think about their own specific relationship to it. There may be a kind of eco-critical awareness that comes out of seeing this show, and I want people to be open to that.

***

From Ansel Adams to Infinity is on view through January 27, 2019, and is free and open to the public.

Seth Feman is the Curator of Exhibitions and Curator of Photography at the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. Feman is responsible for the study, care, interpretation and presentation of works of art in the Museum’s collection and incoming loan shows, as well as developing and curating exhibitions from the Chrysler’s photography collection. He holds a Ph.D. in American Studies at The College of William & Mary, where he also earned his M.A. His dissertation project, which explores modernist painting, photography and urban design in Washington, D.C., has received support from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Getty Foundation, the Terra Foundation for American Art and the University of Chicago. Previously, he worked as an educator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and a writer for the Kennedy Center/VSA Arts, and taught at Lewis and Clark College and William & Mary.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2023 in the Rear View MirrorDecember 31st, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Staff Favorite ThingsDecember 30th, 2023

-

Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCullohDecember 17th, 2023

-

Black Women Photographers : Community At The CoreNovember 16th, 2023