Guy Mendes: The States Project: Kentucky

I remember the first few weeks I started teaching at the University of Kentucky, I was walking around the art building which was my new home and I kept running into Guy Mendes. One has never encountered at more inviting and supportive fellow photographer. Ever since we met, he has been the first to congratulate me on a new fellowship or project. This is made even more meaningful considering Guy’s amazing career. Born in New Orleans in 1948, Guy migrated to the Bluegrass to attend UK in 1966 where he studied under the writer Wendell Berry who introduced him to Ralph Eugene Meatyard, who in turn introduced him to photography the likes of which he had never before encountered. It set him on a lifelong search for a different way of seeing through the camera, looking long and hard at the world at hand.

To inform, and occasionally finance his photo quest he: apprenticed with writer/photographer James Baker Hall in Connecticut (1971); worked as a proof-reader and assistant book designer for the University Press of Kentucky (1972); taught black & white photography in the UK Art Department (1978-1994); traveled with poet & publisher Jonathan Williams of the Jargon Society of Highlands, North Carolina (off-and-on in the 1970s and 1980s); and he hired on at KET, Kentucky’s statewide PBS network, working first as a graphic artist, then as a writer, producer & director for 35 years (1973-2008). He now teaches film photography in the University of Kentucky’s School of Art and Visual Studies. And he is the Head Guy at guymendes.com. He is represented in Lexington by Institute 193, and in Atlanta by POEM 88 Gallery.

His four books are: LOCAL LIGHT (1976), LIGHT AT HAND (1986), both published by Gnomon Press, and 40/40—FORTY YEARS FORTY PORTRAITS (2010), and WALKS TO THE PARADISE GARDEN (2019), published by Institute 193.

His most recent exhibits were WAY OUT THERE—THE ART OF THE SOUTHERN BACKROADS at the High Museum in Atlanta (Spring 2019), and DOWNSTAGE FROM MEATYARD at the University of Kentucky Art Museum (Fall 2018).

His photographs are in the collections of the High Museum, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Odgen Museum of Southern Art, the University of Louisville Photographic Archives, the University of Kentucky Art Museum, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Churchill Downs Racetrack, Maker’s Mark Distillery and Fidelity Investments national headquarters.

People and Places

I have been making photographs since I was a kid, moving up from a Brownie to a Polaroid as a teenager. Back then I thought photography was about replicating reality—until my sophomore year in college when I saw a group of Gene Meatyard’s small black and white prints that ranged from hyper-real, to un-real, to sur-real. Who knew photographs could trade in metaphor and symbolism and mystery? Who knew that a photograph could be like a poem, or a song? Who knew that cameras could take in the ephemeral and manifest the ineffable? Not I. But now, 50 years later, I’m still working on finding out how it’s done. I know it has to do with light & magic, persistence & intuition, love & laughter, smiles & tears—a lot like life itself. – Guy Mendes

James Robert Southard: What were some of your early years with photography? Who were you shooting for and how were those first years.

Guy Mendes: When I was kid with a Kodak Brownie, I took pictures of things like my cat, my feet, my brother and his friends, our new 1956 Ford Victoria and the cabin we stayed for a week in Pass Christian, on the Gulf Coast, and of the Cabildo Museum and St. Louis Cathedral on Jackson Square. [ I have pix] When I was in high school I acquired a Polaroid Swinger and shot with that, and then while working at the high school paper I was able to use a bigger Polaroid. In college, I worked for the campus paper, the Kentucky Kernel, and began to make photographs to accompany the articles I wrote. I bought a used Pentax in ’68, hoping to go to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, but I couldn’t get credentials, which was a good thing, considering that I would have been in the crowd of anti-war protestors who were beaten by the police. But I did learn to use the Pentax, and after two summers of being a Newsweek intern in their Houston bureau, I became a stringer for the magazine back in Kentucky. In 1970 I spent two weeks traveling in the West Virginia and Kentucky coal fields photographing and writing about the destructive practice of strip-mining. My photograph of the gigantic Peabody shovel—the one that John Prine sang about—appeared in the magazine along with my article. [ I have pix] But even as I was beginning to be paid for making photographs, I was getting more and more interested in photographs that didn’t have anything to do with the Who-What-When-Where-Why-and-How of journalism, on account of my new friendship and subsequent travels with Ralph Eugene Meatyard, a professional optician who happened to make photographs unlike any I had ever seen.

You know I had to ask about Lexington Camera Club. I would love to know more about your experiences working in Lexington at the same time as Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Van Deren Coke among others.

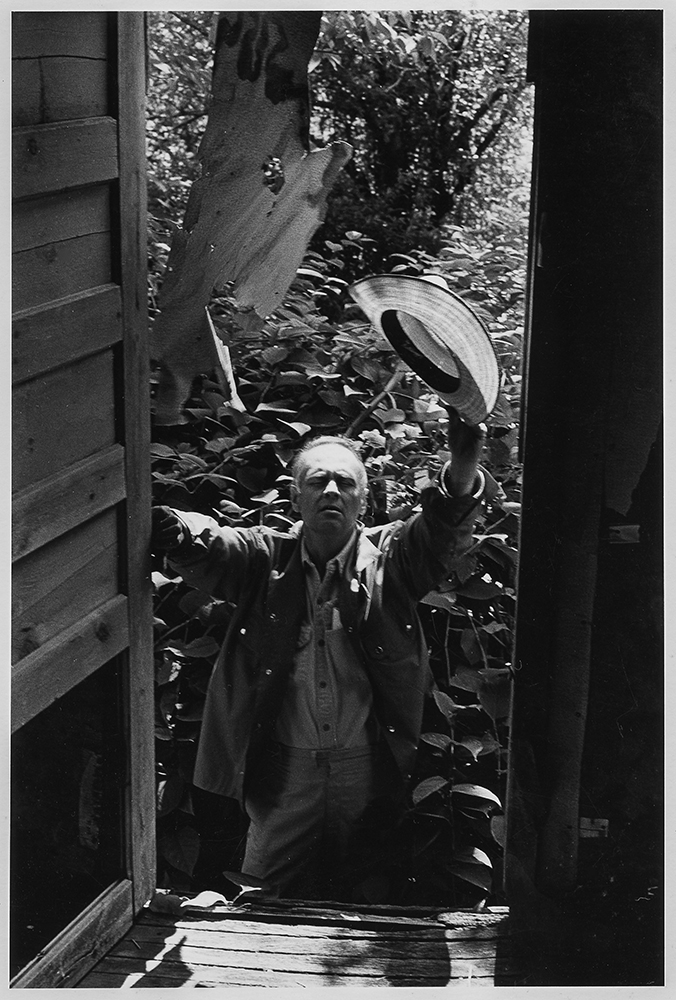

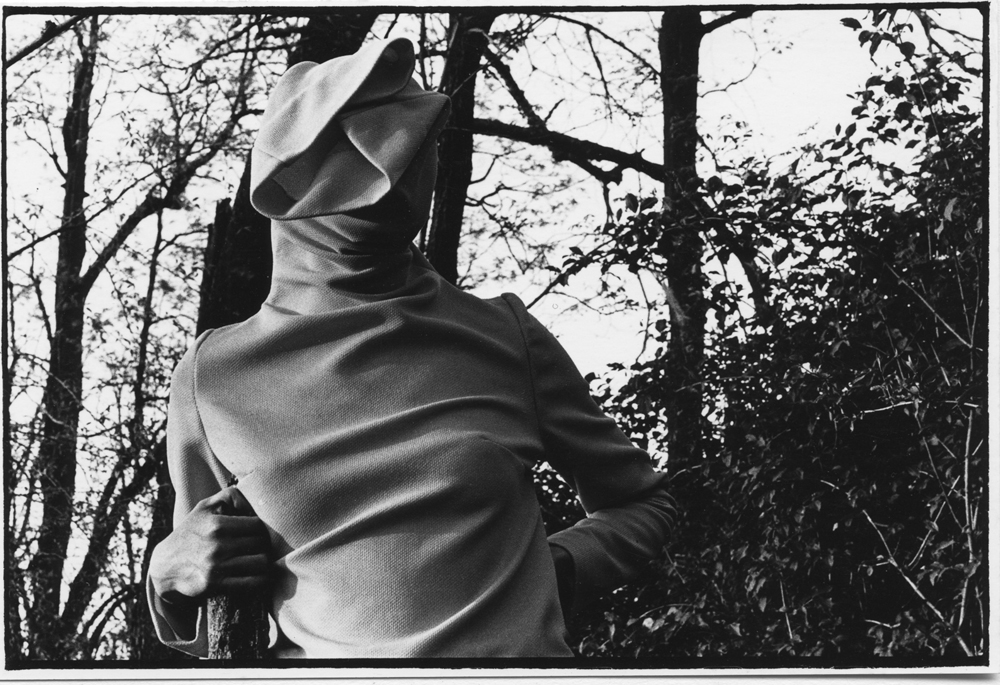

I met Gene and his wife Madelyn in 1967, during a visit to Tanya and Wendell Berry’s farm in Henry County. After that visit I resolved to 1) sign up for Wendell’s creative writing class, and 2) beat it back to Lexington to see an exhibit of Gene’s photographs at a local doctors’ office. The Berry’s seven-year-old son had assured me that this Meatyard dude made some very strange photographs. And he was right! After seeing Gene’s work I began to frequent his business, Eyeglasses of Kentucky, to look at photographs on the walls of his waiting area and in boxes in the back room. On the weekends I accompanied Gene and Bob May on car trips into the countryside north, south, east and west of Lexington. I sometimes stood in a picture for Gene, when he needed a figure in the frame. Sometimes I wore a mask, or something else that obscured my face and allowed me to become an Everyman. I enjoyed playing a role in Gene’s dramatic narratives, and I came to see that the stage on which the figure was arrayed could be as important, or even more so, than the person depicted there. Gene was diagnosed with cancer not long after I met him, but he didn’t talk much about it as he went on photographing, in spite of the chemo that weakened him and caused him to lose weight and his thick black hair. On one daytrip with him into eastern Kentucky, we found an abandoned house to spook around in, and all of sudden Gene took the straw Stetson I was wearing and jumped out of a backdoor with no steps. He turned around in the tall weeds, looked back and me and waved the hat as if to say goodbye. Clearly, he wanted me to make the picture.

Besides going on shoots with Gene, he brought me into the fold of the Lexington Camera Club, which had been meeting once a month since the 1940s. Gene had himself been brought into the fold in the 1950s by his friend and mentor Van Deren Coke. It was Van who had guided the club into the world of fine art photography, encouraging experimentation and the practice of seeing the world anew. Gene, in turn, took me and others under his wing, and for that I am forever grateful. I learned that there was a lot more to photography than what I had been seeing in LIFE magazine and Popular Photography. And I learned more about looking at—and talking about—photographs.

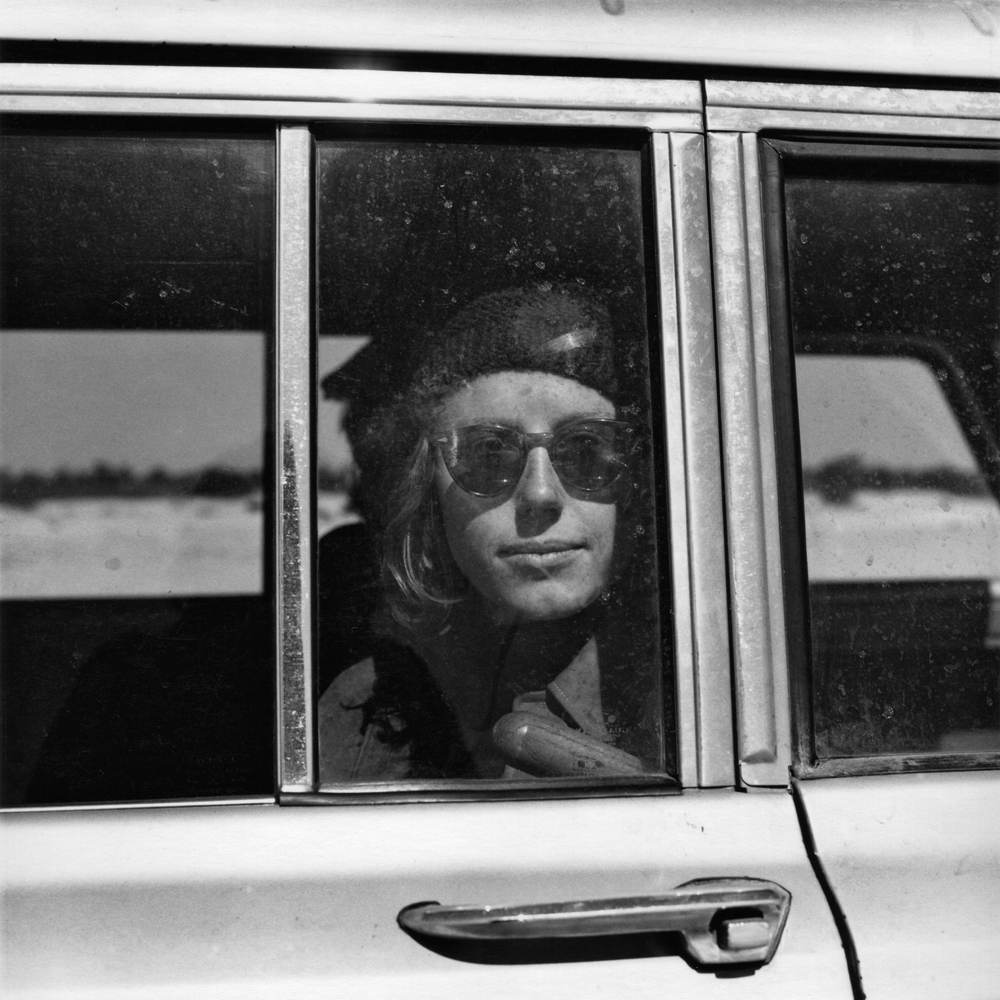

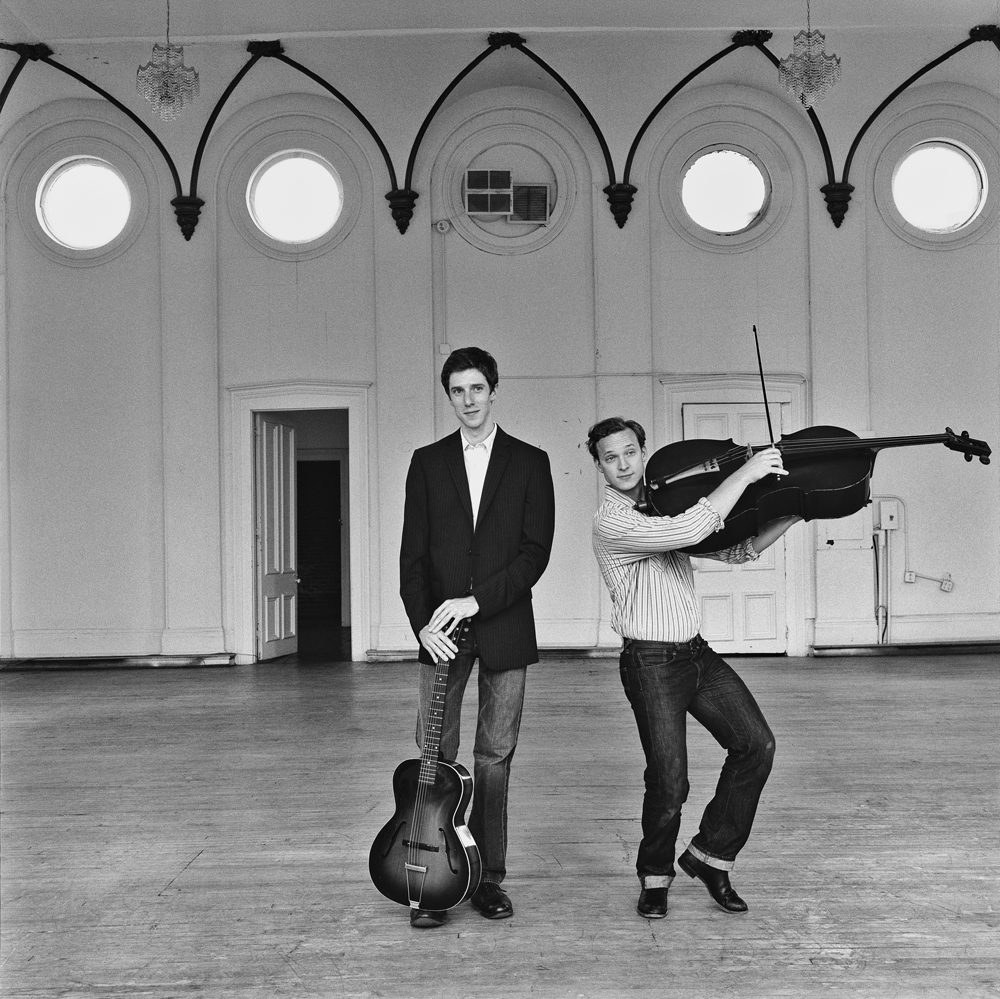

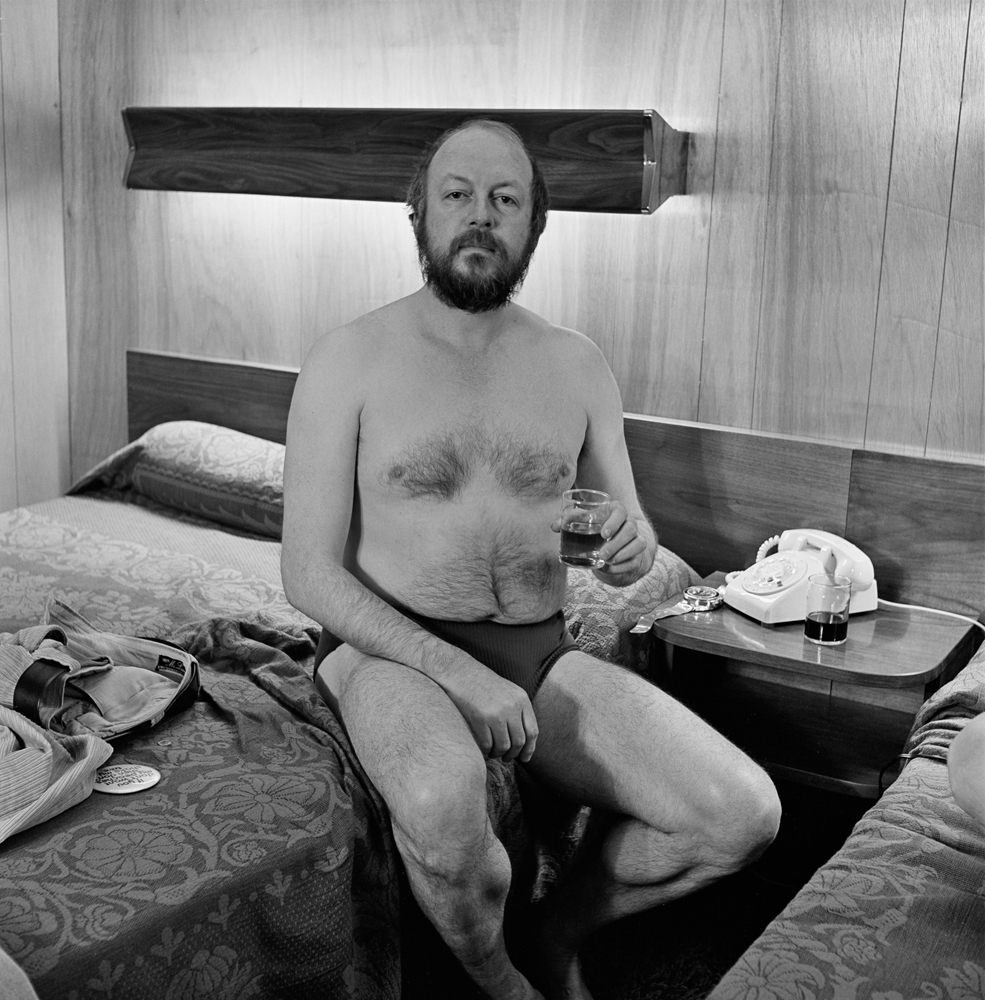

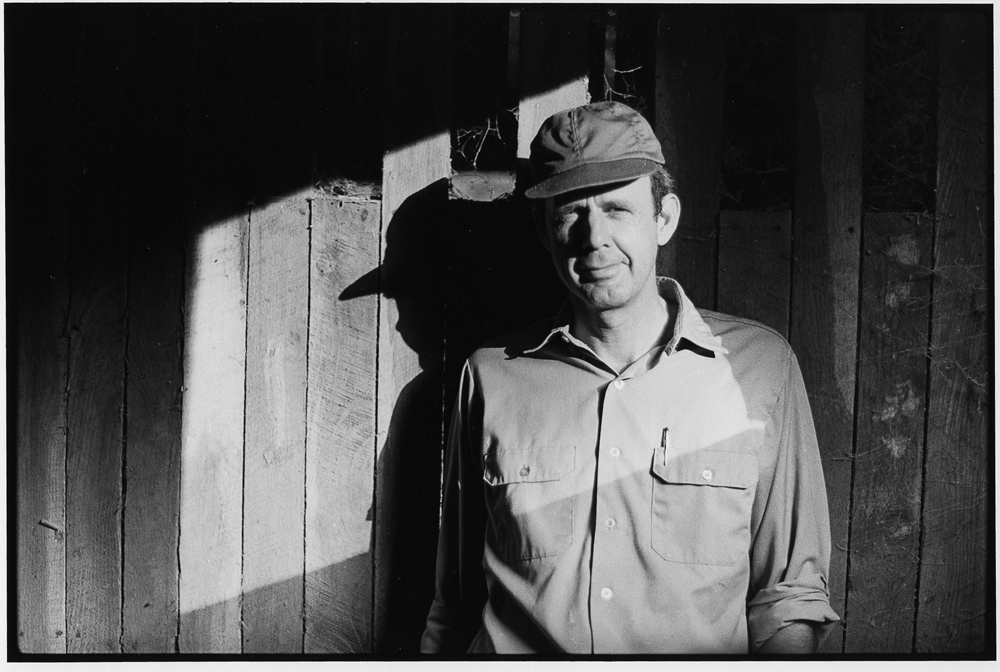

After college I lived for a year above James Baker Hall’s Dogrun Darkroom in South Windsor, Connecticut. Jim was teaching at U Conn and M.I.T., but he had set up a photography business on the side, operating out of an old veterinary hospital. Jim had converted the surgical area into a darkroom. I was an unpaid apprentice, learning about photography from Jim in exchange for whatever work I could do for him on shoots and in the darkroom. Besides occasional commercial work Jim was making several kinds of photographs: nature pictures, figures, experimental work from sandwiched negatives or slow, handheld exposures. He thought that photographing people was a way to get a glimpse of their gestalt. He liked to say that a good portrait is given as well as taken. That means it’s up to the photographer to elicit the gesture, the expression, the attitude, the je ne sais quoi from the subject that reveals something about their inner mojo. Jim was very good at coaxing and cajoling. I can still see him, holding out his left hand as if he were reciting a poem, clicking his tongue and tripping the shutter of his Leica, tripping the light fantastic.

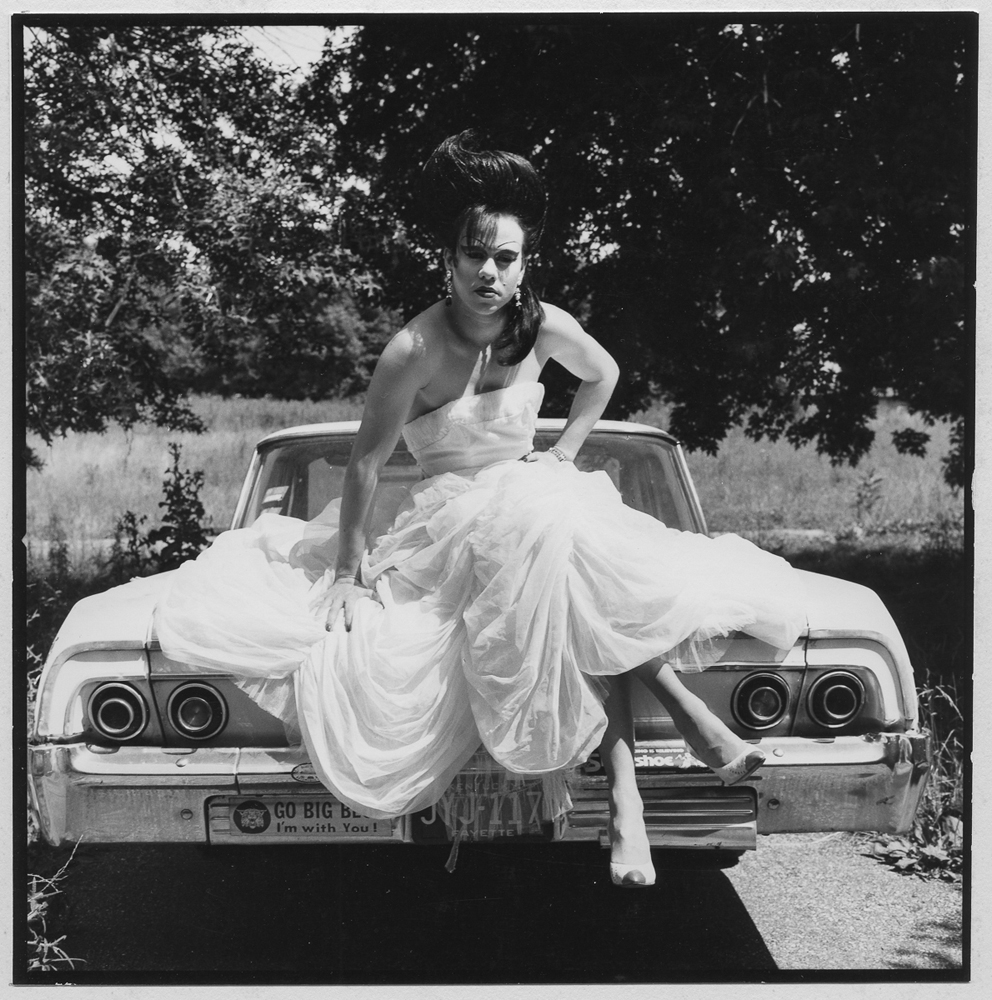

Jim’s ideas of what makes a good portrait, and Gene’s searching to find a worthy stage led me to an appreciation of pictures of people that are more than just what they look like on the surface, pictures that reveal something of a person’s world and their particular stance in it.

And if some photographs are like poems or songs, then some photographic portraits are like odes–odes on the “intimidations of mortality” to borrow Ed McClanahan’s corruption of Wordsworth. Susan Sontag’s statement “All photographs are momento mori” would second that emotion. But at the same time, there are ways that portraits can serve as exaltations and exclamations, as testament to the strength and perseverance of fellow travelers who have helped show us the way.

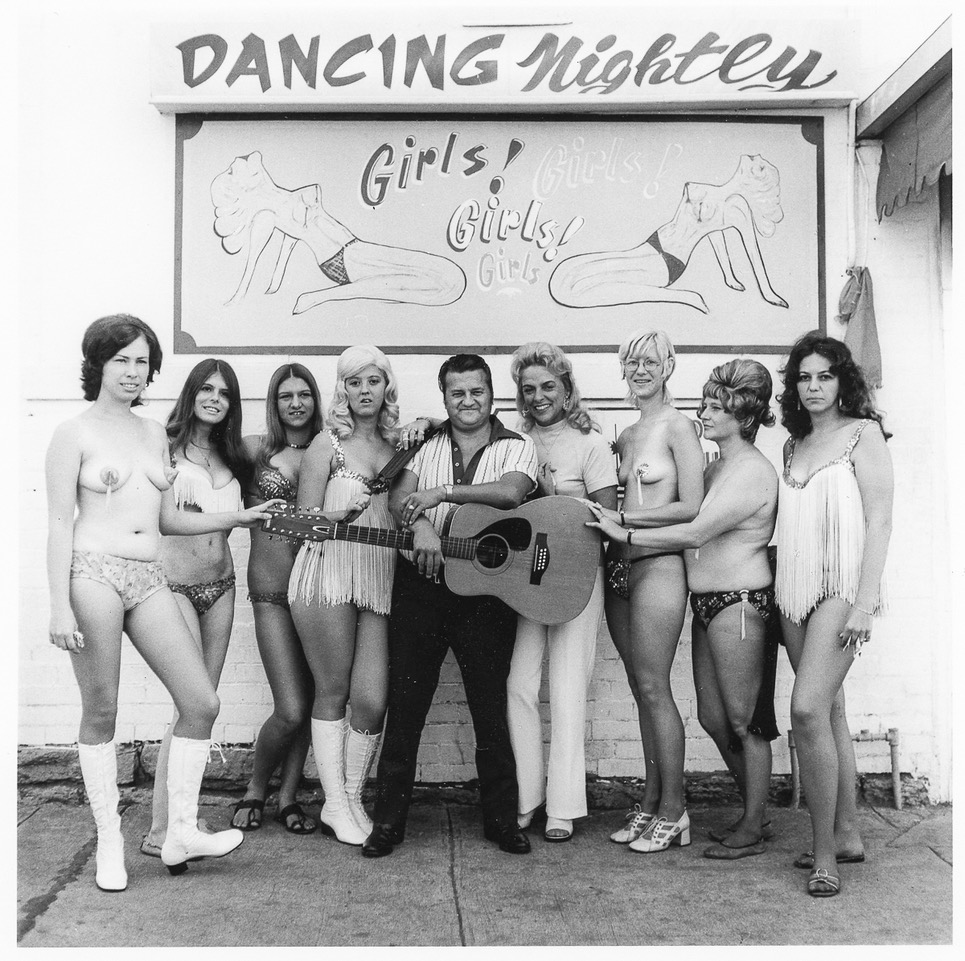

Since 1969 I have photographed family members, friends, and a wide assortment of people who might appear normal at first glance, but actually they are seers, soothsayers, spirit guides, mentors and muses. They are the stars of my own personal firmament, they have inspired and amazed me and made me laugh. The portraits pay homage to lives that shine across the fullness of time.

I am interested to know more about your landscape work. I like how in some of your books, you pair them seamlessly with your portraits. What choices are made when you are picking these locations?

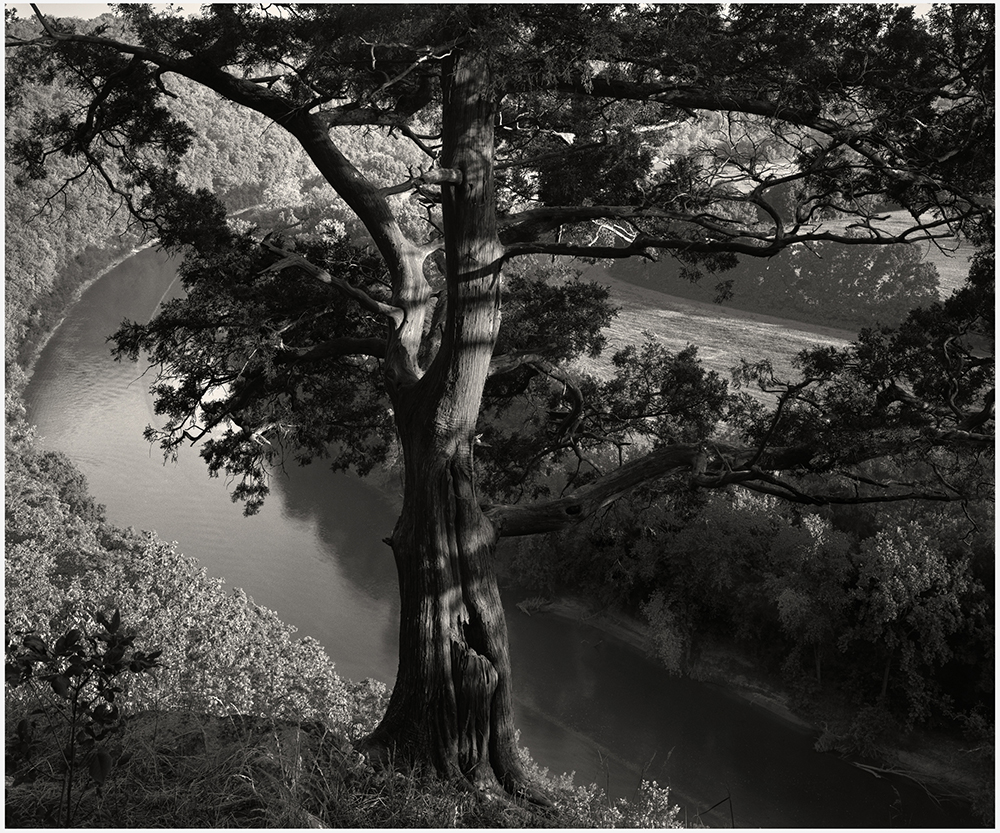

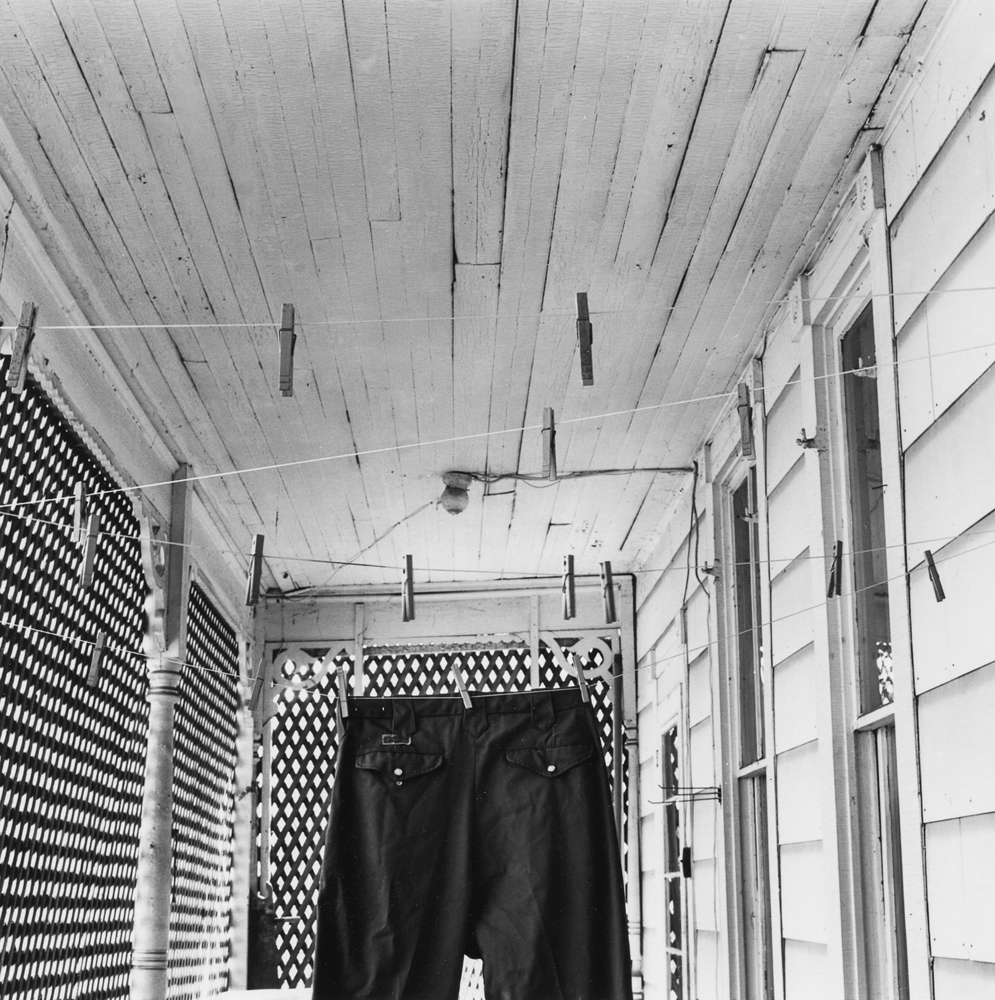

Besides the classical genres of landscapes, portraits and figures I have been drawn to images that hinge on irony and humor, usually involving some hand-of-man foolishness in the built environment, like portals that go nowhere. But most of my landscape work owes to the fact that I’m a card-carrying, tree-hugging-environmentalist who likes to celebrate this place which has been put in our hands for a very short time. I want to make photographs that are like prayers offered up in the face of the disregard and disrespect and outright exploitation of our natural heritage.

When looking at your work, I immediately think about the wondering photographer. Do you look to put yourself in unique situations, or is your photography just a reaction to your wondering and/or relationships with your subjects.

“I Wonder as I Wander” was a folk song by John Jacob Niles, and I subscribe to that notion, except I think you can wander abroad in the big wide world, or you can wander in your own backyard. I wandered aplenty when I was in the 70s and 80s, whenever I could get away from work. Then I took up residence as a white trash tenant on an old farm near Nonesuch, KY, and lived there for 17 years. I had 50 acres and a mule. Really. And 12 head of cattle and an Angus bull, some chickens and a sow and piggies. Pretty good for a city boy. I was trying to get back to nature, but I was in over my head. Frederick Sommer said, when people say they’re getting back to nature, I wonder where they’ve been? Having grown up in uptown New Orleans duplexes with tiny backyards my urge to get back to nature must have come from a previous lifetime. Suffice it to say the sow and the mule were smarter than I was, but I hung in there, and I had eggs and beef and garden veggies, but also the amazing opportunity to focus my attention on the incredible Kentucky landscape. It afforded me a unique opportunity to look at the landscape on a regular basis, and to see things I might not have seen otherwise. I worked in a darkroom I built in a small room on the back porch of the old farmhouse. It didn’t have running water and it was heated by a wood stove. I moved back to Lexington in 1991 with my wife, two dogs and two cats. I borrowed darkrooms to do my work until 1994, when I had a studio and darkroom built in my backyard. My paying job prevented me from spending all my time is the studio. Until 2008, when I retired from public television and moved into the studio full time.

Just by paying attention I feel like I’m adding day-by-day to a core sample from my tiny corner of the world. A core sample is a long, cylinder excavated from a deeply dug hole. It yields layer upon layer of time, along with remnants of lives that were lived during those cross-sections of the near and distant past. Whether it’s composed of ancient ferns, or photographs made over the course of one person’s lifetime, there is an encapsulated energy waiting to be tapped. With the former, the tap brings power to turn on the light. With the latter, the spigot produces light that reveals the power—the power found in evocations of time and place, of people and things that have come and gone. The summoning up of those spirits brings joy and pleasure, but also longing and dread. Excavation has its risks.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026