Jeanette May: Tech Vanitas

Projects featured over the past several days were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Tech Vanitas, by Jeanette May.

Tech Vanitas

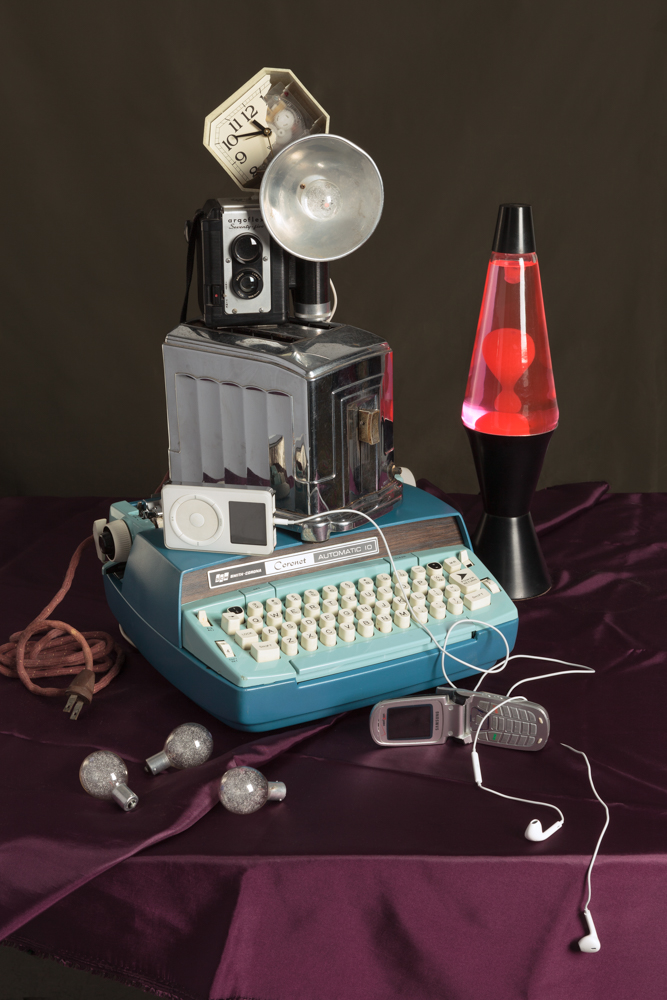

As widely observed, we live in an age filled with devices that make domestic life faster, smarter, easier, and more complicated. Consumers may choose from an astounding number of tech products. Items fill our shopping carts and our homes. The more we yearn to keep current—the newest phone, computer, camera, audio system, espresso maker—the more we produce, consume, and discard. Cutting-edge technology becomes outdated, embarrassing, quaint, collectible, and finally, antiquated or forgotten. My Tech Vanitas photographs embrace the anxiety surrounding technological obsolescence.

The original vanitas paintings celebrated the new wealth of The Netherlands in the 17th Century. Their still lifes recorded the affluence of finely crafted domestic merchandise: silk, porcelain, Venetian glass, silver goblets, and cultivated flowers. By including skulls and references to time, vanitas paintings also signified the inevitability of death. Contemporary still lifes exist in the form of advertising imagery; the newest gadget is carefully styled and photographed to convince potential owners of technological ascension. Perhaps more than death, we fear becoming Luddites.

Just as the Dutch Golden Age still lifes portray the abundance afforded a prosperous culture, Tech Vanitas embraces luxury, honors design, and acknowledges the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures. For these contemporary still lifes, I utilize digital photography to capture precarious arrangements of domestic technological ephemera: a coffee percolator and film camera teeter atop a shiny boombox that spews magnetic tape across the keys of an Underwood typewriter. My photographs employ anachronistic technologies to confront still life’s traditional tension between temptation and rejection of worldly goods.

Daniel George: What draws you to the still life genre—particularly to create images that reference Dutch vanitas paintings?

Jeanette May: When I began planning this project addressing the contemporary tension between desire for and anxiety about technology, vanitas paintings struck me as an ideal point of comparison. I reread Svetlana Alpers’ book, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the 17thCentury, which made an impression on me while studying with Allan Sekula. Alpers examines the still life within the greater context of Dutch culture: its newfound wealth, access to merchandise through international trade, interest in science and technology, and emphasis on craftsmanship. Referencing Dutch vanitas also presented me with the opportunity to create painterly photographs. Both my training and art practice have included painting, and part of my goal in this project was to honor beautiful design while also raising questions through the subject matter. Attention to beauty is part of what makes the still life potentially unsettling—both in Dutch images and, I hope, my own. Both the form (careful composition and sumptuous colors) and content (all those products!) are slick and alluring; everything is still but precarious and in disarray—it looks so good but where is it leading us; what’s really going on?

DG: In your artist statement, you write about the anxiety associated with technological obsolescence. How do you characterize this?

JM: I think a lot of the tension concerning technology has to do with the pressure to keep current, to always use the newest of the new devices, which demands considerable time and money. It is cliché to say our possessions connote status, but that does nothing to reduce the pressure. Coupled with this is the question of what happens to those products (and people) that no longer keep pace—the distinctive and rare transform into revered antiques, and the rest are forgotten in landfill. As suits reference to the vanitas, my images seek to render that tension through composition: my first still lifes in the “Tech Vanitas” series are all vertical compositions with the objects stacked precariously. The stacking is meant to promote anxiety in the viewer. I later switched to a horizontal format, similar to the “banquets” style of vanitas paintings, in which the anxiety is expressed by including more and more gadgets and a disheveled composition.

DG: As I look at some of these images, I cannot help but find humor in the quaintness of the objects-themselves—especially as I consider how some of the assemblages have been entirely replaced by a single, handheld device. What advantages and disadvantages do you see in current technology being so streamlined?

JM: Purposeful humor is an element of much of my imagery, including this series—I selected some of the tech objects specifically for their charm or quaintness. I’ve also included some “Easter eggs” such as a bent paperclip, an essential tool for the home computer far later than one would have hoped! I am no Luddite—it’s my iPhone in one of the images (indeed, my old, iPhone). Contemporary devices are both more efficient and (in some cases) more beautiful than their clunky predecessors. I think the disadvantages, however, lie in our dependence on the newest object of desire. While vacationing in Yellowstone last summer, we found ourselves without cell service and thus frequently losing track of each other. My brother, despite being an electrical engineer, always travels with a case of old tech, so we hiked with walkie talkies.

A recent World Science Festival lecture moderated by David Pogue raised just these issues: what comes after the smartphone; we already have devices that can interact directly with our brains, including implants—would you adopt the latest device via brain surgery; will you need to in order to “keep up with the Joneses”? Are we obsessed with the new; are we dependent upon our tech; what happens to the old device, and to those with a fondness for it? None of these are rhetorical or settled questions. Again, the vanitas’s tension and ambiguity is apropos, with its flaunting of coveted objects while (ostensibly) reminding us they are worldly distractions from mortality.

DG: Your photographs mix technologies from a range of time periods. Why was it important to represent variations of the past, rather than sticking exclusively with more contemporary examples?

JM: My “Tech Vanitas” photographs were inspired by the need to keep up with ever-changing technology and dispose of the obsolete, so I arranged gadgets from different time periods in each of the still lifes. The juxtaposition of old and new suggests the passing of time. We are often surprised by how quickly technology becomes obsolete. Some of the “new” technology I included in these still lifes might be out-of-date before the photograph is ever exhibited! I find that viewers of my still lifes are drawn to the items remembered from their past, sparking conversations about their fondness for, and the limitations of, a discarded radio, calculator, or Palm Pilot.

DG: Why do you feel it is important, per Dutch vanitas tradition, to remind the viewer of the futility of pleasure and the certainty of death (technologically speaking)?

JM: I know some scholars feel the vanitas paintings were moralizing, but I’m not trying to express the futilityof pleasure in my photographs. Rather the opposite. I hope to remind the viewer of the pleasure found in beautifully designed technological objects. When talking about technology it is easy to settle into moralism, lamenting loss of human connection as we are more technologically connected, or celebrating the human achievement and aspiration of our rapidly evolving tools (sometimes in the same conversation). My work examines the present and the past of technology without easy answers but rather, like the Dutch vanitas, with a sense of wonder and trepidation.

Jeanette May is a photo-based artist using a critical, sometimes playful, approach to investigate representation itself. Early training as a painter is evident in her carefully arranged compositions and rich color palette. Ms. May “makes” photographs: constructed, staged, lit, and carefully considered. Her recent still life series, Tech Vanitas, embraces the anxiety surrounding technological obsolescence. Ms. May received her MFA in Photography from CalArts and her BFA in Painting from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She has been awarded grants, fellowships, and residencies from the NEA Regional Artists’ Projects Fund, Brooklyn Arts Council, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, Illinois Arts Council, Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, Ms. Foundation, and Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts. Her work is exhibited in galleries and museums internationally, including New York; Washington, DC; Chicago; Los Angeles; Toronto, Canada; Sandviken, Sweden; and Athens, Greece. Ms. May teaches at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York City and lives in Brooklyn.

A solo exhibition of Tech Vanitas will be on display at the Fitton Center for Creative Arts in Hamilton, OH from August 10th – October 4th, 2019.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Wishmaker and The Landau GalleryFebruary 27th, 2024

-

Interview with Kate Greene: Photographing What Is UnseenFebruary 20th, 2024