Kari Wehrs: Shot

Projects featured over the next several days were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Shot, by Kari Wehrs.

Shot

From scenes of gun violence that make the national news, to my 61-year-old mother suddenly deciding to carry, incidents of gun use haunt me with curiosity and fear. Having no personal attachment to guns, I am grappling with present day societal reverberations and implications of the gun in American culture.

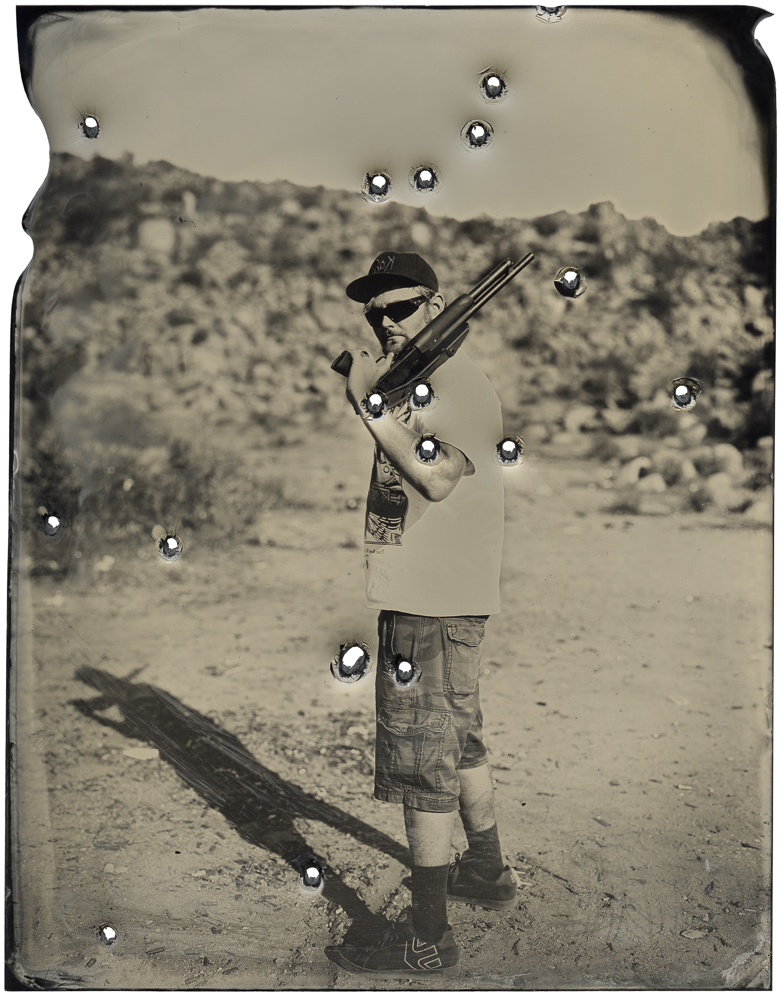

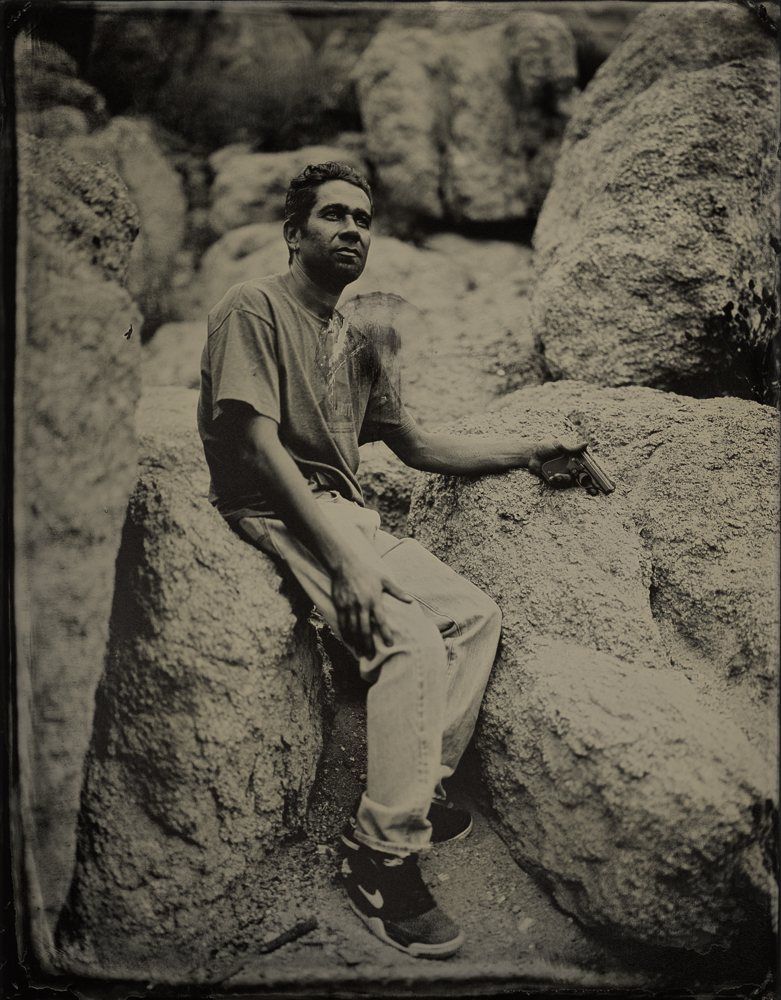

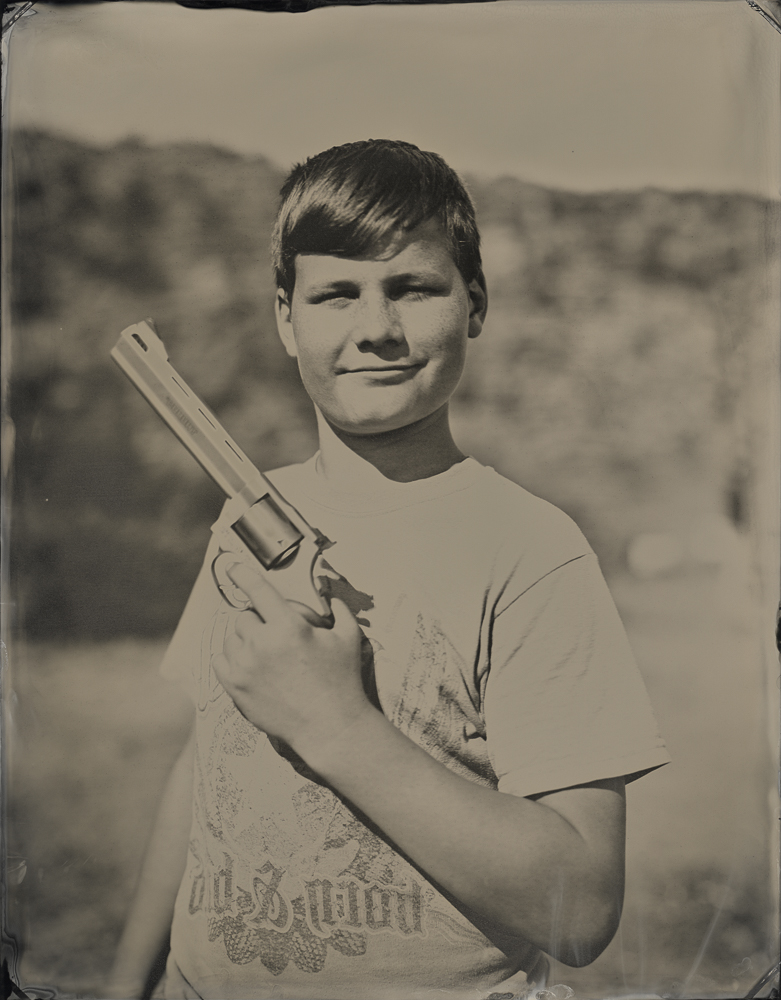

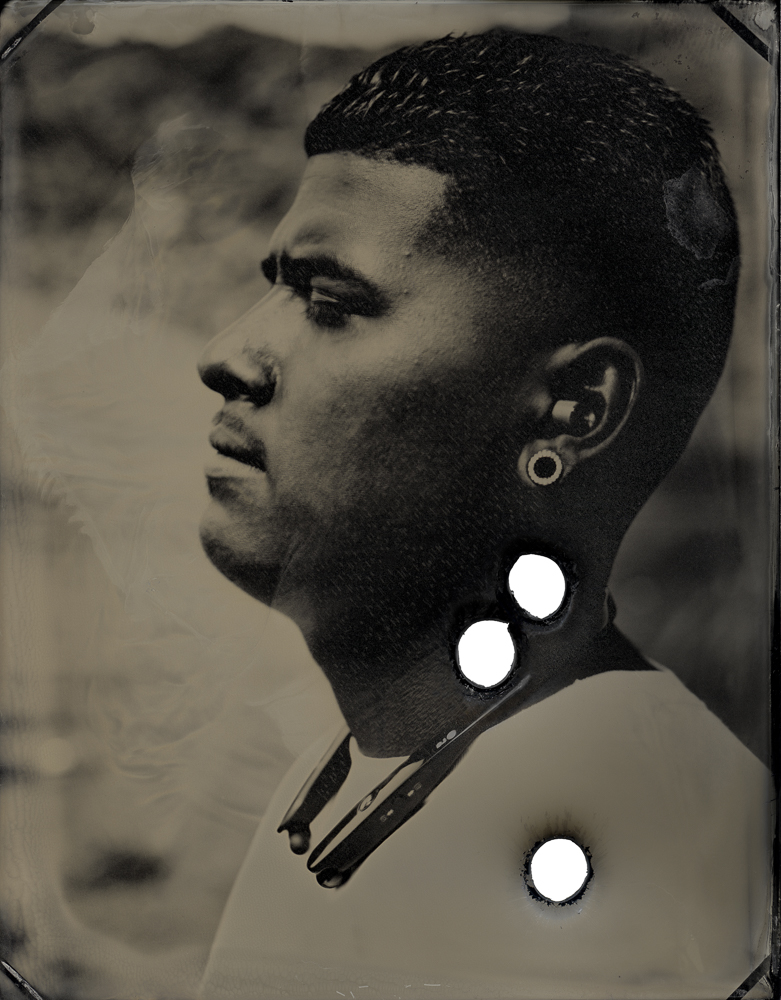

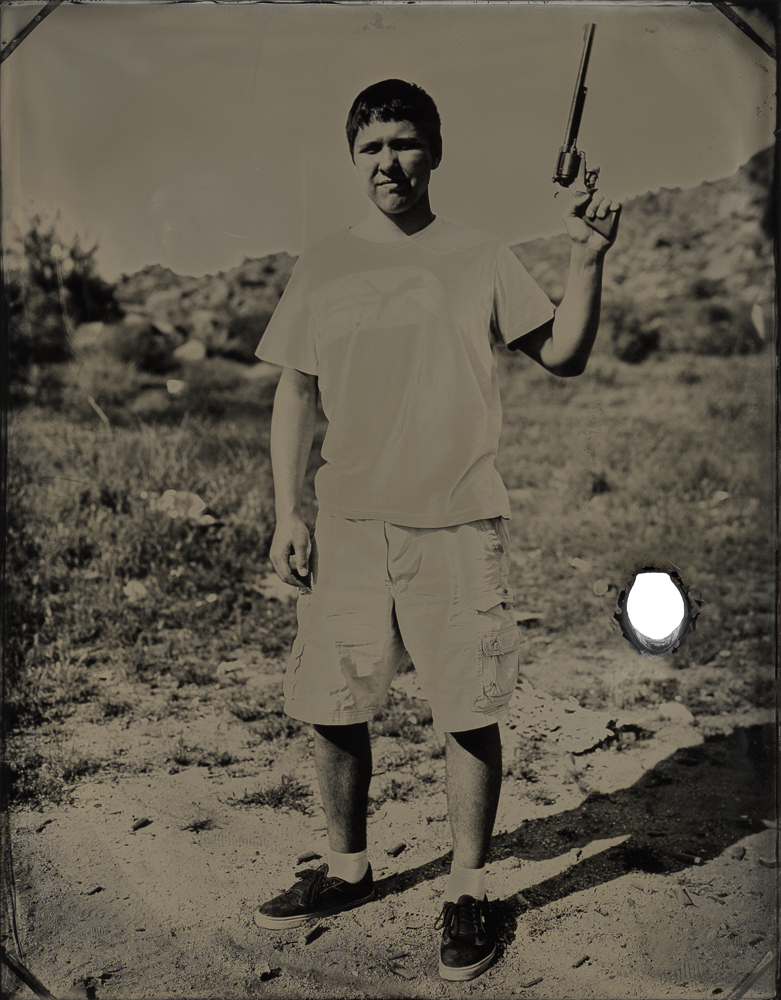

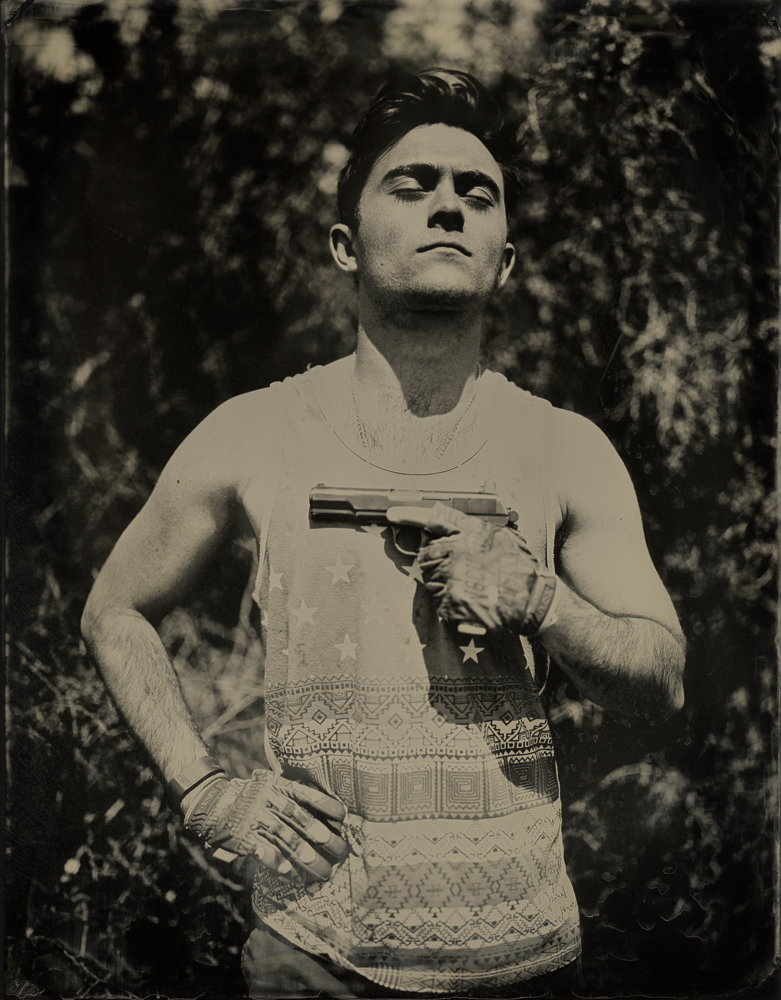

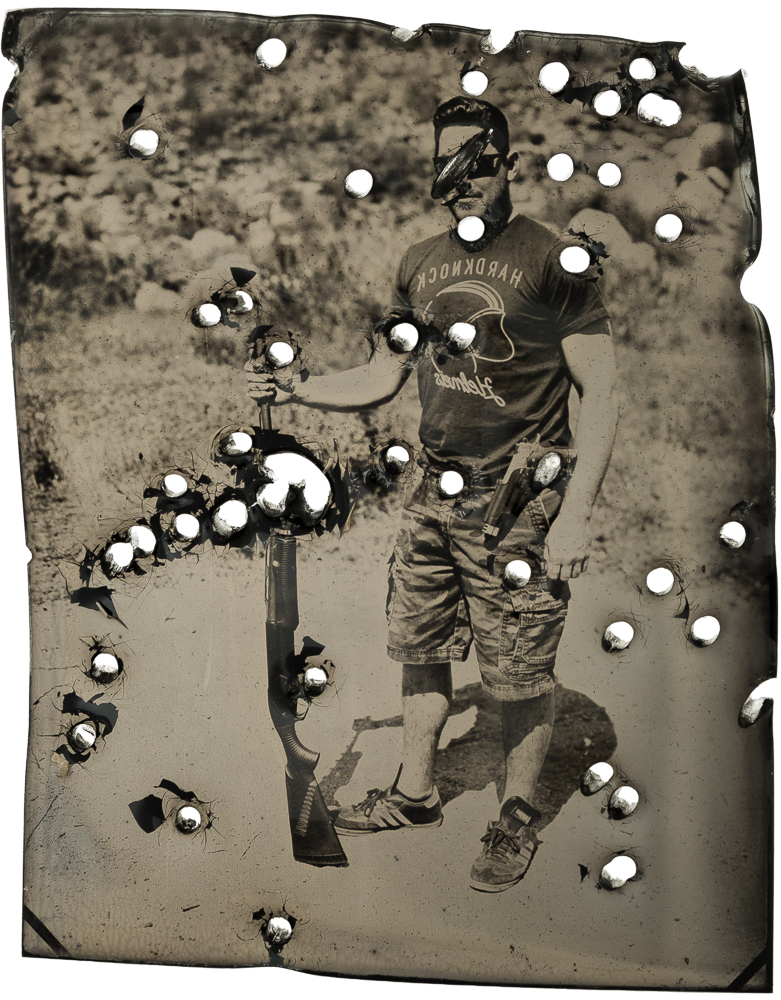

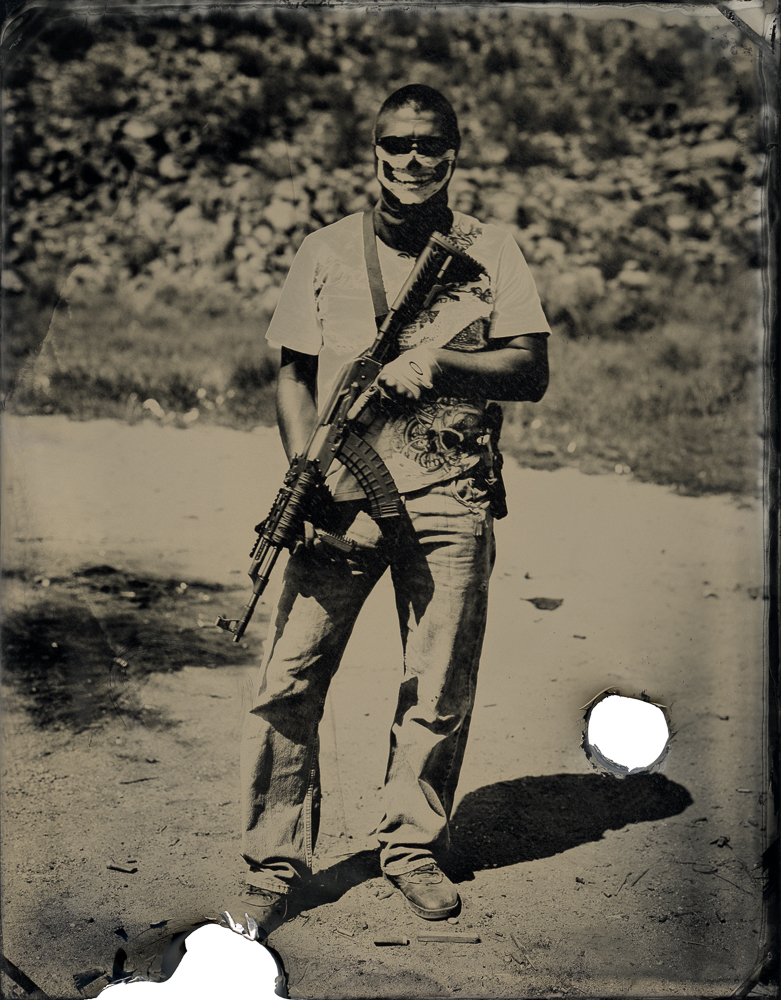

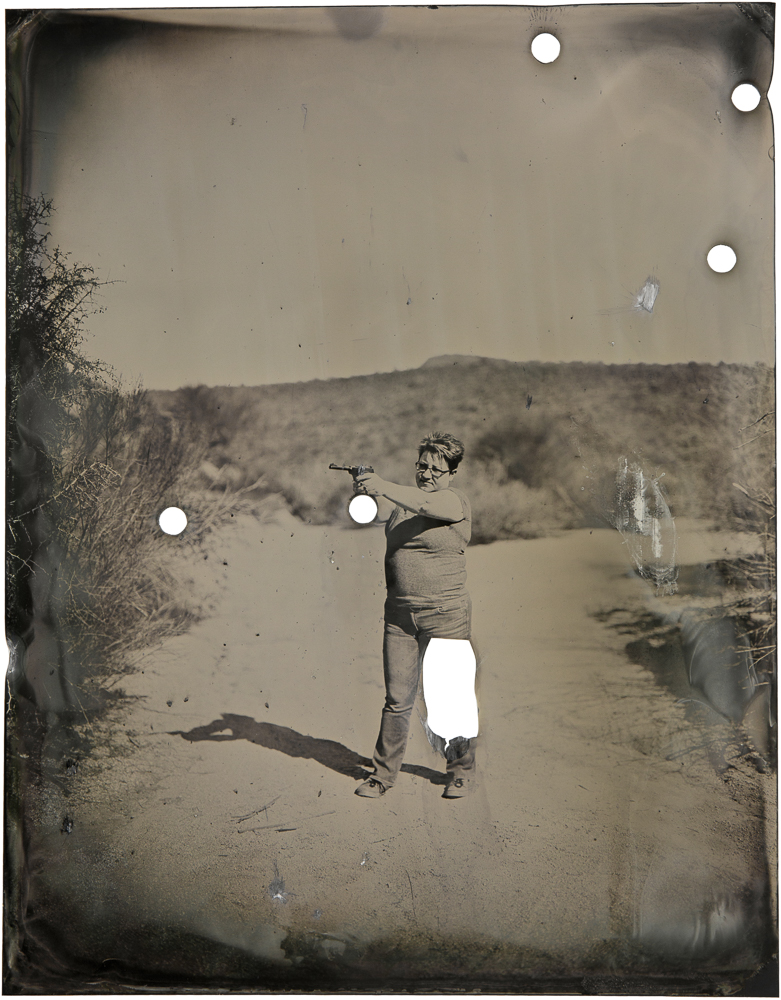

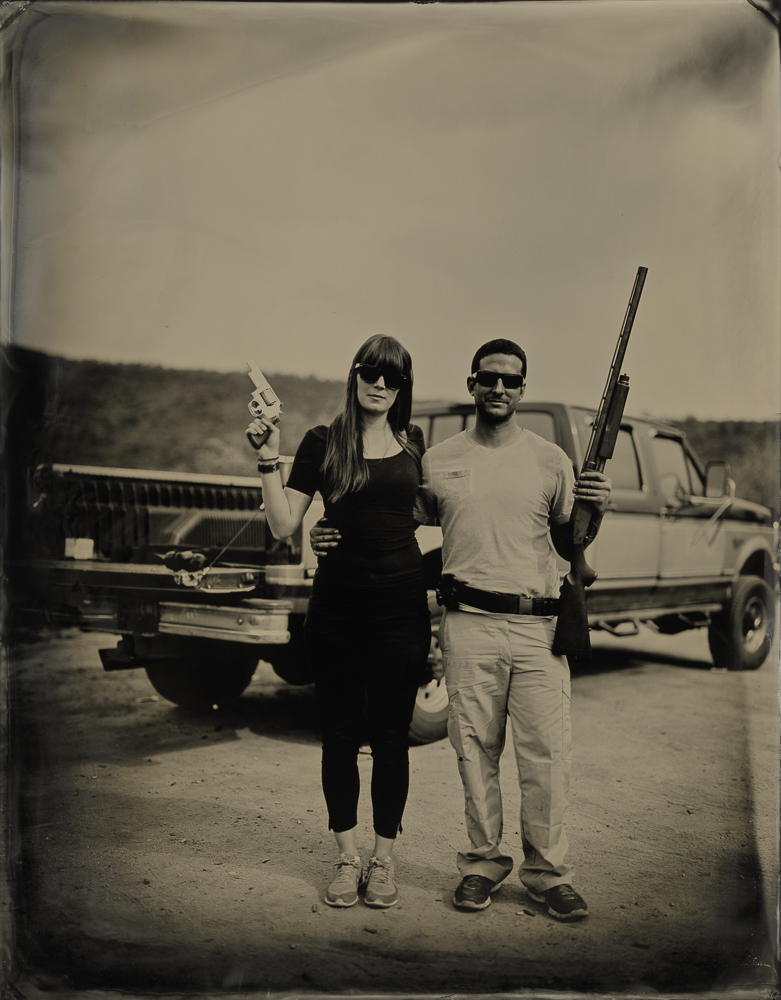

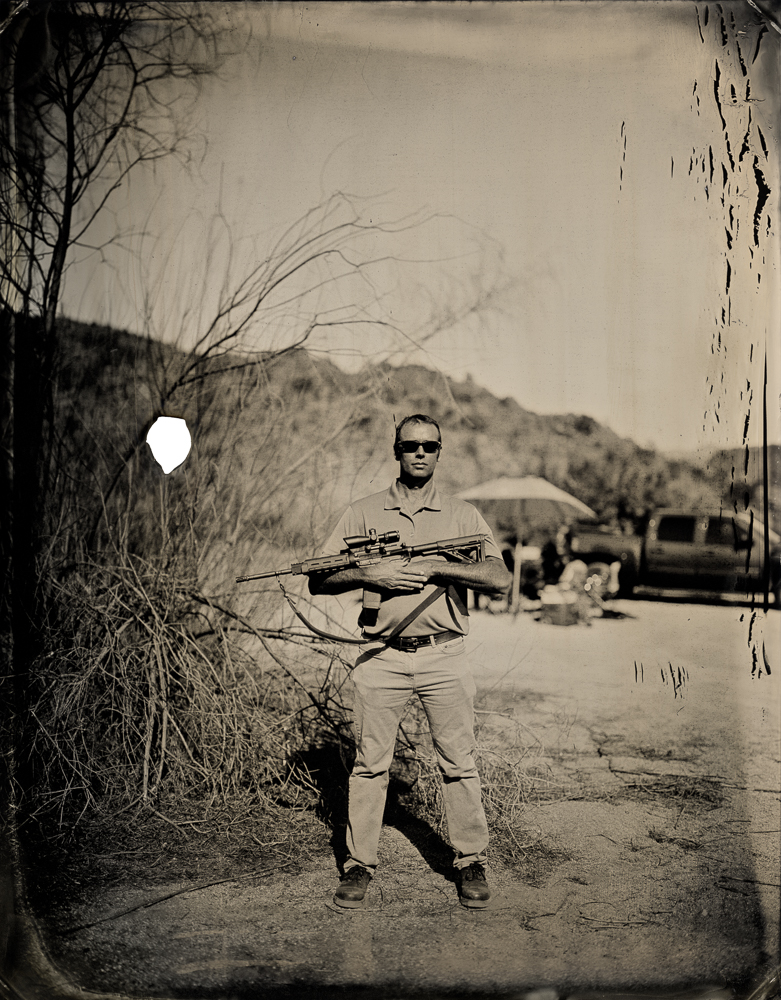

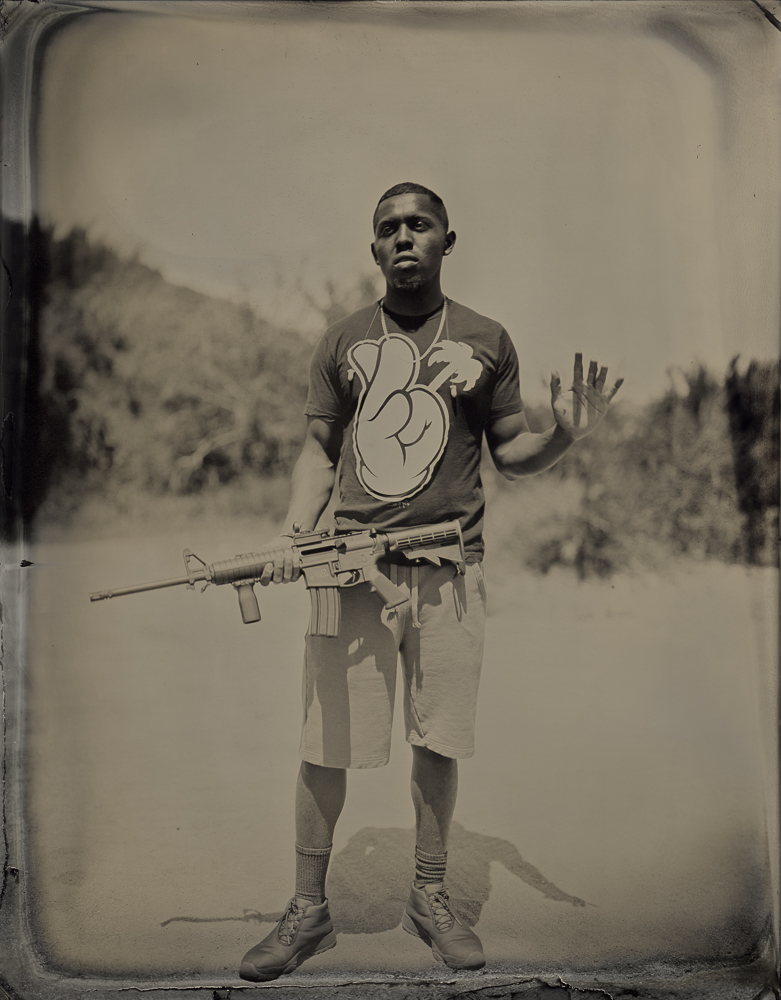

To create this series, I set up my darkroom tent and tintype gear at known target shooting locations in the Arizona desert. I meet gun enthusiast strangers and ask if they are willing to participate in my project. I create their tintype portraits, and when complete, I give them the option to use the image as target. Some take part – leaving bullet holes in the plate. “Shot” refers simultaneously to my use of the camera and the participant’s use of the gun.

Tintypes were the primary form of photography during the American Civil War – another time when the country exhibited vast divides. Soldiers often posed for their tintype in military uniform and with weaponry. My use of this form of photography in contemporary time elaborates on these connections to history.

I view this project as a method to investigate and provoke both personal and collective consciousness. How might we need to re-consider this time in our history? When do/did our rights become our burdens? How do we want to think of our social or political opposite, and how might crossing uncomfortable boundaries potentially lead to positive change? How do we freshen the all-too-often predictable “gun debate”, and instead pursue an exchange to reconcile our differences and move beyond our current impasse?

Daniel George: In what ways did your experience with your mother inform the beginnings of this project, and what evolved as you made this work?

Kari Wehrs: I felt flooded with a mix of perspectives and emotions after my mother told me that she started carrying a handgun. It brought about a realization for me – regarding social, political, and simply human, concerns surrounding gun use that I wasn’t comfortable with. Sadly, at that time, I placed my own mother in my mind as “one of those people”…she sort of took a role as “other”, or I took that role in comparison to her. The catch is that my mom and I are also very close, so this odd tension felt amplified. I began to question where, how, and why boundaries might be broken down. I knew that I needed to create work that could touch upon the framework of ideas, questions, and tensions that I was feeling.

I have been surprised by the openness of the exchanges between the participants and myself as I’ve made the work. The polarization of this topic becomes diffused through personal experiences. I’ve learned that nuances in opinions and thoughts surrounding the gun provide for overlap among various other personal identifiers. It has been enlightening to engage and ask gun enthusiasts to work on something with me – and to have some conversation regarding the gun and divisiveness being felt today in our time and culture.

DG: Did you have any reservations creating this work? If so, what were they?

KW: Absolutely. In the beginning it was all scary. I was nervous about the guns, nervous about the people with the guns, nervous to make work about a “hot” topic, nervous to be judged by anyone with any opinion on the issue, nervous about my (and others’ who joined me) safety while in the field. Keep in mind that if someone had told me a few months before I began making the work, “you’re going to create images about the gun”, I would have laughed out loud. So I suppose I began the project while still in a state of surprise. As I made the work, most of these fears dissipated, though not entirely.

DG: Why was it important to make these photographs as tintypes, as opposed to some other process?

KW: There is a conceptual marriage of photographic process (creating tintypes) and its related cultural significance (specifically in America) that is unique and intriguing. Most people have encountered some historical tintype objects and correlate the tintype with the American Civil War. My hope is that this association is provocative.

It’s also important to make this work in tintype for it’s material and stylistic visual allure. The tintype in physicality feels to me to offer a romantic layer to the work…while the project can feel “heavy” in content, it can also feel visually beautiful and attractive. There is a duality to the concept of the project that the material choices get to exemplify.

Last, the process is slow and it is unique to the average person that I am encountering. Unless you are very interested in historical photographic techniques, the method of creating a single tintype is likely something that you have not seen before. All of this helps with my rapport with potential participants. It is a “slow and steady wins the race” sort of mentality.

DG: Do your subjects vocalize their thought process on whether or not to shoot their portrait? I am curious how that is determined. Why did you ultimately decide not to shoot the photograph of your shadow?

KW: Sometimes, yes, but not every time. The people who do not choose to take aim at their portrait are usually very quick to say that they like the image/object and they don’t want to ruin it. Many of the participants who choose to shoot at their image often try to take aim at a part of the plate that doesn’t include their body though some aim for the plate in general and their likeness on the plate is less of a worry for them to mark. Once in a while a participant will think about it aesthetically…so say they aim and shoot once, they might see what the object looks like and potentially then choose to aim for another spot, to balance it out visually. Or another time a young man participated and since he was a competitive shooter, he tested the pattern of his shotgun on other objects before he took aim at his portrait.

Before engaging in this work, I had never shot a gun, so maybe that is why I had no desire to shoot at my self-portrait. I never felt it would somehow become a more meaningful object to me if I did shoot it. Though I did decide to let my shadow lay on top of a shell-littered ground. I’d rather think of my self-image as being about an artist and a witness.

DG: How do you see this project contributing to the conversation on guns in America?

KW: I hope that the work is provocative and that it asks viewers to assess their own consciousness in terms of gun use and gun issues in our country. While I have felt that the project is partially a warning and a reminder, I also view it as hopeful in the sense that these photographs represent a coming together and an exchange across the divisiveness of this issue.

Kari Wehrs is a photographer and educator currently living in Tempe, AZ. She attended Arizona State University for her MFA in photography and graduated in the spring of 2018. Kari teaches summer courses at the Maine Media Workshops + College in Rockport, Maine, where she has been a workshops instructor since 2012. She is a represented artist with the Tilt gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025