Dawn Roe: Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Wretched Yew

Projects featured this week were selected from our call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Wretched Yew by Dawn Roe.

Dawn Roe works with still photographs and digital video in both singular and combined forms. Her projects poetically and critically engage with photo-based forms of representation through perceptual studies of culturally charged sites of significance, as well as those presumed to be neutral.

Roe’s photographs and videos are exhibited regularly throughout the U.S. and internationally. Recent major exhibitions include Time as Landscape: Inquiries of Art and Science, Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Winter Park, FL (2017); Strange Oscillations of Vibrations and Sympathy, ISU University Galleries, Normal, IL; and The Florida Prize in Contemporary Art, Orlando Museum of Art (2016). Work from her current project, Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning, was included in solo and two-person exhibitions during the summer of 2018 at Tracey Morgan Gallery and Revolve (with Leigh-Ann Pahapill) in Asheville, NC.

The recipient of awards and fellowships including The Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation McKean Grant, Broward County Division of Cultural Affairs Public Art Commission, The United Arts of Central Florida Artist Grant, and The Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs Artist Grant, Roe’s imagery and writing has also been included in many print and on-line journals including Aint-Bad, The Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography’s series Frame/s, Oxford American, and the Routledge print journal, Photographies.

Roe received a BFA from Marylhurst University and an MFA from Illinois State University. She currently serves as Professor of Art at Rollins College in Winter Park, FL. In 2013 Roe founded the public art project Window (re/production | re/presentation) and serves as the curator. Her work is represented by Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville, NC.

Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Wretched Yew

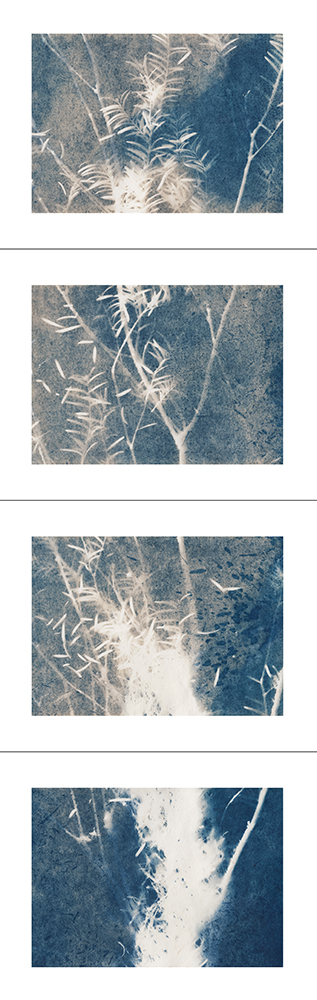

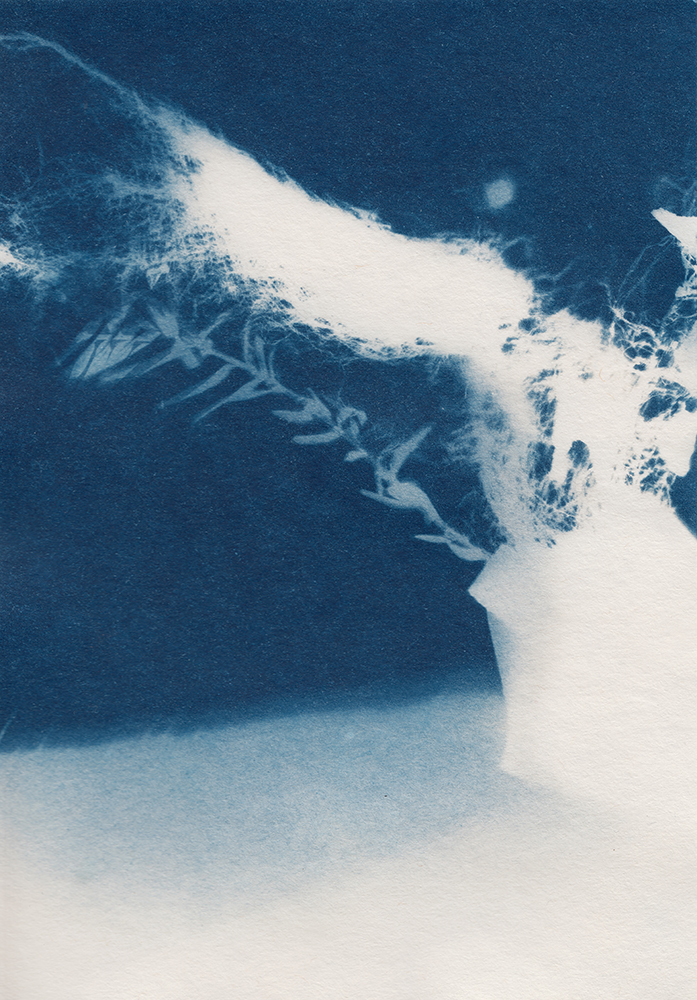

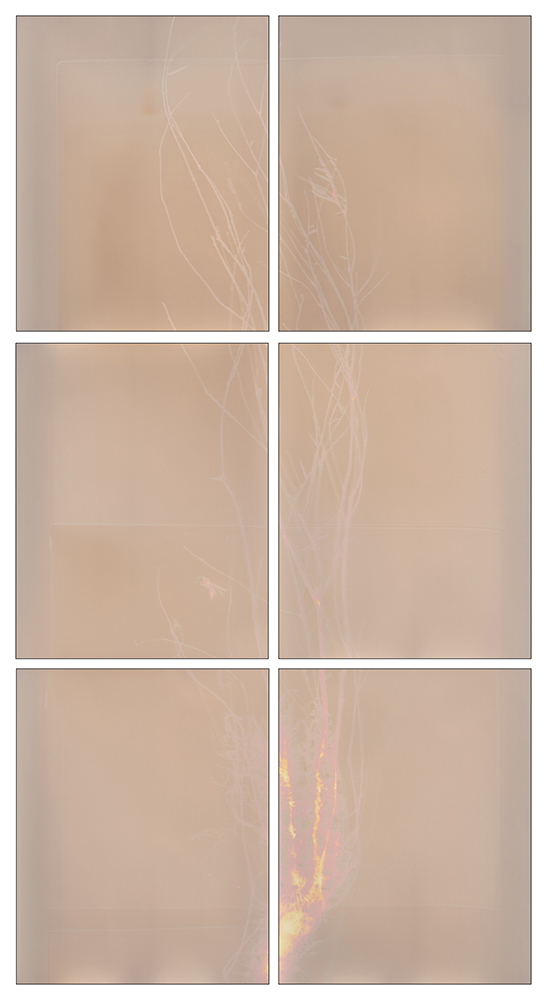

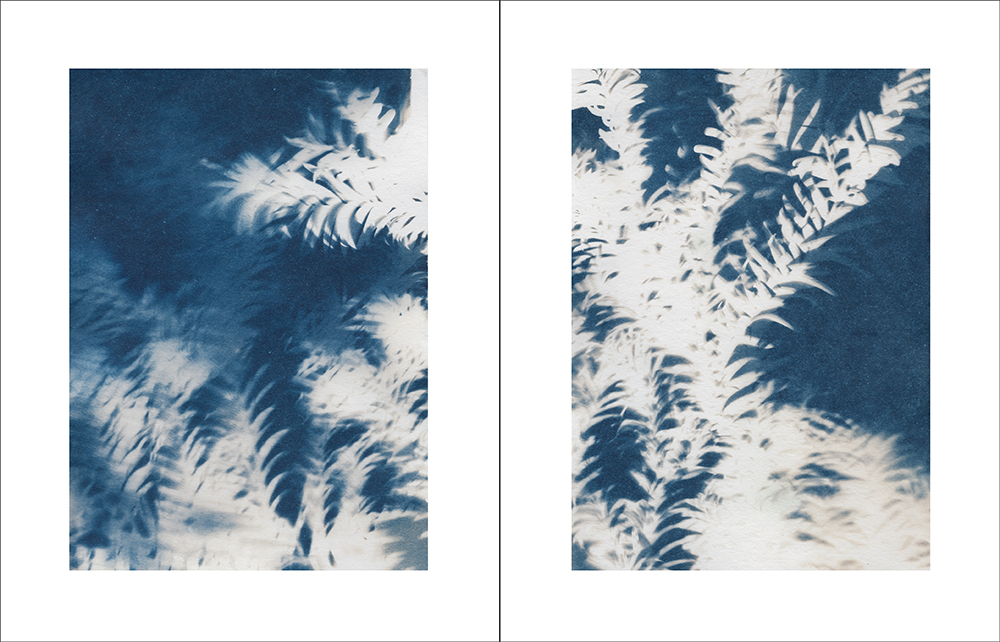

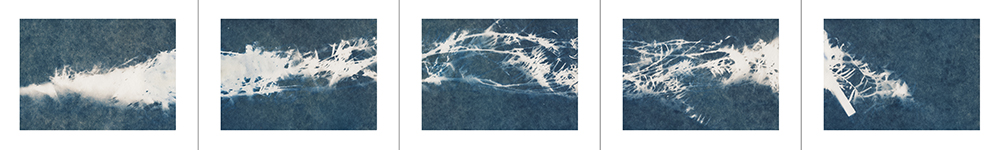

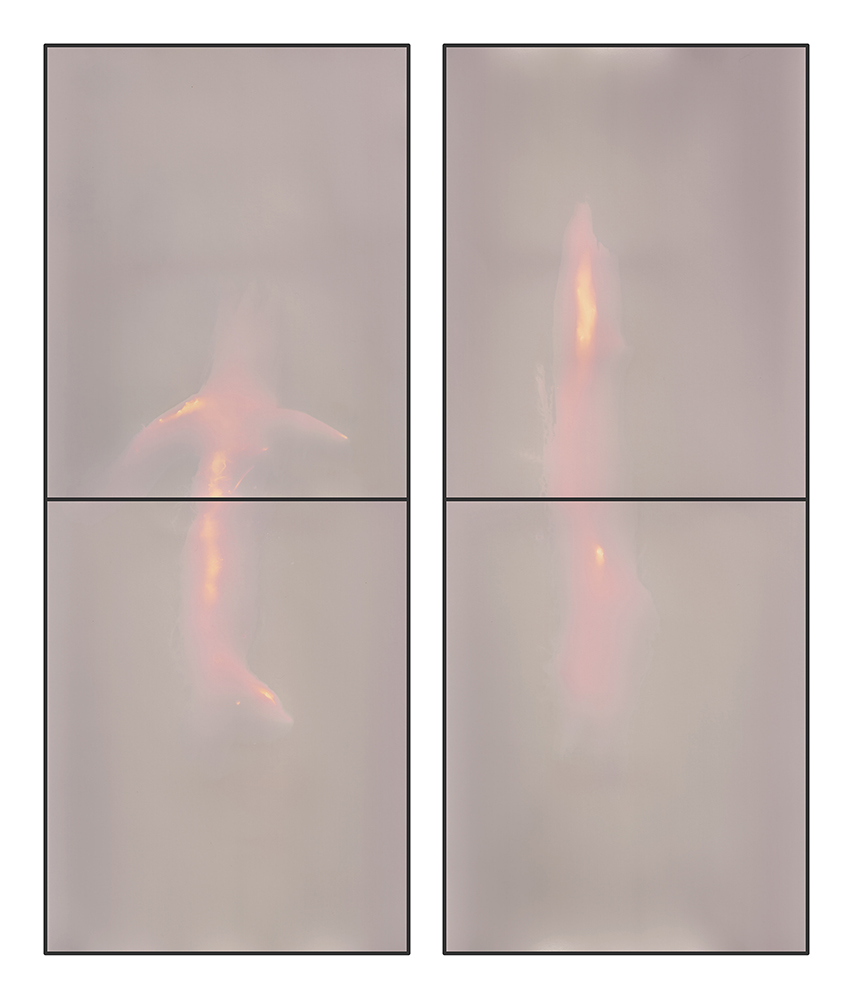

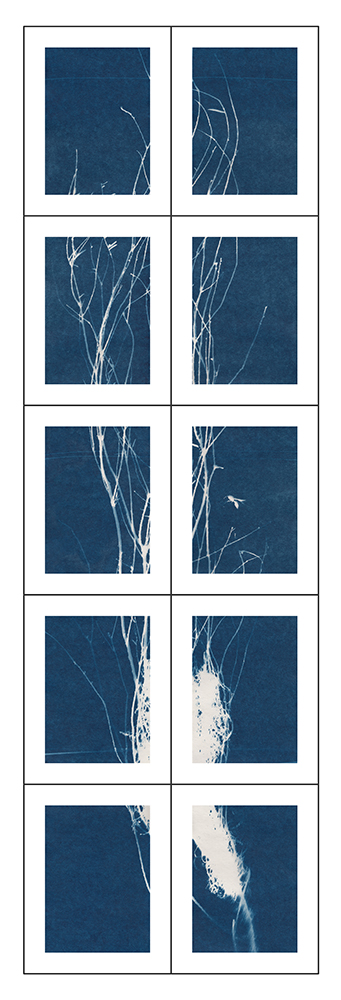

Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Wretched Yew is the second sequence of an ongoing series using the process of recording via photography, film, video, and sound to draw upon the pathos embedded within sites of sorrow and distress while revealing moments of resilience. This phase of the project relates the taxus brevifolia genus of yew tree native to the Pacific Northwest – known for its healing properties, and as a symbol of death and regeneration – to my own experience in the region during a tumultuous time when the pervasive sight of clear cut hillsides served as the visual backdrop to personal struggles with addiction, depression, and loss.

These adjacent recollections led me to consider the cultural and ecological legacy of this species as indicative of ongoing cycles of neglect. Though long revered by indigenous cultures, the Pacific Yew was primarily disregarded by foresters of the settler state as an insignificant understory component – both economically and environmentally – until it was discovered to generate a plant alkaloid highly effective as a chemotherapy drug. Though now synthetically produced, a government contract with a global, pharmaceutical company resulted in the decimation of much of the already sparse population of yew when harvesting of its bark occurred in the 1990s. Yet, due to its indestructible nature and ability to easily regenerate, isolated pockets of both old growth and more recently sprouted Pacific Yew continue to thrive as vital components of the ecosystem.

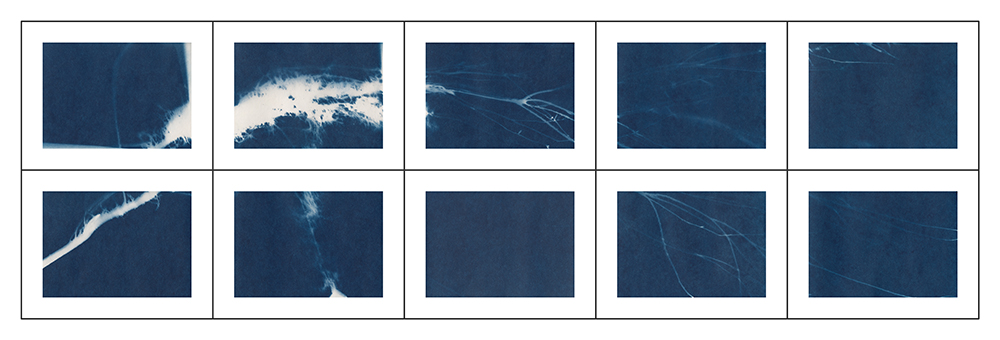

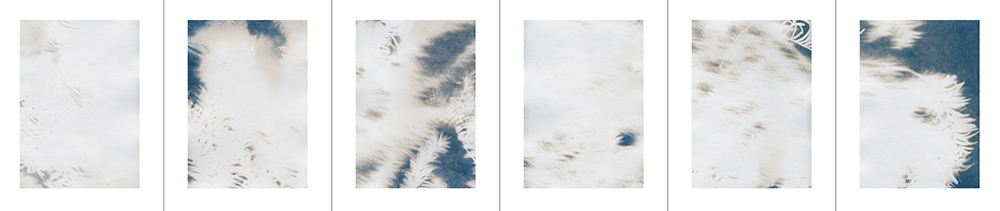

During repeated trips to Oregon, a number of these trees were located. In conjunction with video recording, sun exposed images of and around the trunks, branches and leaves were produced over extended intervals. UV-sensitive contact printing processes were incorporated as a primary image capture technique due to the prolonged exposure required by these methods. The resulting imprints archive and represent duration in a manner distinct from the moving image trace of the same instance, allowing for an examination of the space between record and document, referencing the simultaneous passage and persistence of time. As a straightforward yet precisely indexical camera-less form of transcription, the use of the photogram also serves as a deliberate nod to the DIY ethos of punk culture, connecting back to my formative years in Portland and the musicians who are collaborating on the soundtrack to the accompanying video work. Together, the individual project components serve as collective acknowledgement of the unsettled grief that permeates this mental and physical space, functioning as a set of discrete elegies apprehending the residue of dormant trauma by making visible that which endures.

Daniel George: What was it about the yew that prompted you to traverse the country and include it within your series?

Dawn Roe: A quick caveat – this may be a bit of a lengthy response to a pretty straightforward question, but…here we go! The short answer is Virginia Woolf prompted my interest in the yew which led to this series, though Woolf’s writing heavily informed several past projects as well – and this trajectory is (I think) significant.

Around 2009 I began a series called The Tree Alone that ultimately morphed into a more extended group of works, The Weight of Centuries. This work drew heavily on Woolf’s novels, To The Lighthouse and The Waves – particularly their nonlinear structure and deliberate rendering of botanical and atmospheric matter as relating to cycles of time, memory, and mourning.

In 2016 I was asked to participate in an exhibition by curator, Kendra Paitz, Strange Oscillations and Vibrations of Sympathy, which featured work by contemporary female artists that acknowledge or reference women writers. This opportunity led me back to The Waves with a specific intent to draw upon and incorporate the language itself as text-based components within a fragmented video accompanied by a long, linear photo-based composite. During this process, I came across a line I hadn’t paid much attention to in prior readings,

“Let us stop for a moment; let us behold what we have made. Let it blaze out against the yew trees. One life. There. It Is Over. Gone Out.”

This led me to fixate on the yew tree and begin researching the significance of the species – many will know it as the “tree of the dead” as it is often found in churchyards throughout the U.K. in particular, but also due to its poisonous attributes. The yew is also incredibly resilient and thrives in difficult conditions. Not surprisingly, it has healing properties as well. In particular, its bark was found to contain a compound that was synthesized for use in a cancer treatment drug.

Learning of this is what led me across the country to locate this particular genus – taxus brevifolia – native to the Pacific Northwest in the U.S. and Canada. In the 1990s, the yew population in this region was almost decimated due to irresponsible harvesting by a pharmaceutical conglomerate that was given a government contract. Though I was living in Portland throughout this decade, I was unaware of what was happening to the yew. But, this time frame also coincided with a pretty horrific spate of unrelated clearcutting that is stamped upon my own memory as the visual backdrop to a tumultuous time encompassing mental health struggles and significant, personal loss. So it seemed appropriate to bring these sites and situations together – of ecological and individual devastation – in relation to the Pacific Yew in its current state, as a continually recurring perennial that persists in the face of everything, year after year after year.

DG: As you work on projects, you make notes and publicly share your progress via blog. Tell me more about your research methodology, and the significance of sharing your creative process.

DR: Well, I feel a bit behind in this aspect currently – in terms of producing content on my research blog. That particular mode of working developed in response to a search for strategies to remain productive with a full-time teaching schedule, and began in 2012. Organizing my thoughts and forming them into a written passage after working in the field or in the studio is a really effective way for me to keep track of how my ideas and process are informing one another – and chunks of time can really fly by during the school year so these entries can serve as reminders, helping me pick up where I left off. Because I’m often pulling from a wide array of sources throughout the cycle of any given project – texts and articles, maps, various word definitions from OED (one of my favorite sources to help me think deeply through a specific term), or rabbit hole encounters via Internet searches – it helps to get something written down so I remember why I found it important in the first place. And, I’m not shy about my works-in-progress being perceived as a bit clumsy or undeveloped. I like to put it all out there for a number of reasons – to show my students that projects don’t just miraculously show up complete and resolved; to share progress with curators as a means of supplementing studio visits; to instigate conversations with fellow artists and writers; and, to hold myself accountable to my own work.

Lately, the public side of my research has taken the form of sporadic Facebook or Instagram posts where smaller snippets of relevant research or writing might accompany a set of images. Even though I allow the blog entries to be somewhat loose, that kind of writing (for me) requires bits of uninterrupted time and I guess I just haven’t been finding as much of that lately. Thank you for this reminder, though!

DG: Along with photography, the larger body of work also incorporates film, video, and sound. Why do you feel it was important to incorporate additional sensory experiences to the project?

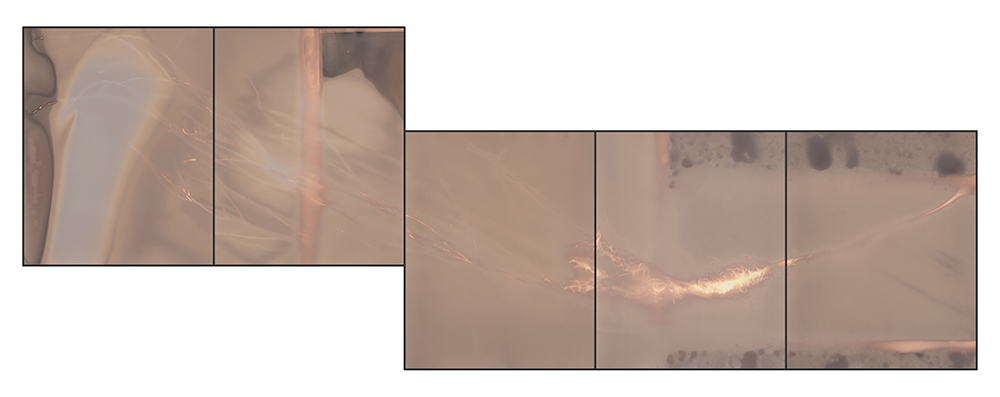

DR: Before moving more deliberately to photography, I initially studied experimental filmmaking at The Northwest Film Center in Portland, Oregon. All my work beginning around 2009 has included both still photography and film or video in direct relation to one another – even in works that only exist in moving image format, the still image or freeze frame is generally a dominant component.

Though I remain indebted to certain aspects of documentary tradition, I just don’t find straightforward documentation (on its own) to be effective or productive in helping me connect with or think through the ambiguities of representation – in particular, the optical aspects of reproduction. I want to be reminded of the ephemerality of images, and how they come to be as well as disappear. Light and sound waves are of course invisible and fleeting but produce refractions and vibrations that have a physicality, as captured in various lens-based and audio formats.

With Wretched Yew, I was curious to think about how I might construct an image of the tree(s) without (entirely) repeating pictorial traditions of landscape. My use of cyanotype and other UV-based methods comes from this, as I wanted to obtain direct imprints of both the organic and situational material – as plant-based x-rays and durational exposures, both influenced by climate and time. These resulting traces are halted and serve as documents/specimens, whereas the time-based video clips captured function as records/recordings. Time is extended differently in each of these archival registers – as forever persisting within the document and repeatedly recurring in the recording.

The afterimage is also something I am thinking about here – not only in terms of the persistence of vision that results in the illusion of movement, but also the general optical burn of color and light and the potential impact of sound to heighten these phenomena. The video components of Wretched Yew are still very much in progress, but my intention is to rely on these aspects to heighten the dirge-like qualities of the soundtrack. [Quick bit of mention and a HUGE thank you to my musician friends in Portland, OR who contributed their time and talents to the audio tracks – Jerry (A) Lang; Jennifer Shepard; Jillian Wieseneck; Dan Eccles; Dean Miles; Mike Lastra.]

DG: You are utilizing elements within the landscape as a representation of human experience. Describe the ways in which the natural world can effectively function as autobiography.

DR: Jeeze, that’s a tough one. But something I’ve been simultaneously tackling head on and absolutely avoiding for a number of years now. I have such a hard time with the idea of the natural world at all, as being distinct from or somehow hierarchically positioned (depending on one’s perspective, I suppose) either above or below other kinds of worlds. Clearly this has much to do with my own ambivalence or discomfort working in landscape as a place rather than a space, or as a situation – perceptual or psychological, I guess. For myself, I tend to prioritize the perceptual for the reasons I detailed above, but (as with Wretched Yew, in particular) have become more sensitive to the potential of place and material as harboring valuable prompts that can be quite generative. And this is where autobiography – as an account, or the process of writing (or imaging?) an account, of one’s life – may come into play, perhaps?

I think I might point back to the writing of Virginia Woolf again. In The Waves, alluding to the ebb and flow of tides forms a foundation and references to trees are constant. This work is sometimes described as being autobiographical and, to me, it is the landscape and how it is imaged in the writing that corresponds with Woolf’s (possible) attempt to account of her life – more so than the characters within. One of the many aspects I take from this novel in working through my own relationship to nature is the idea of dwelling. There is something particular about how elements within the landscape provide an outline of sorts, or a structure, allowing us to have something to place ourselves against.

DG: Within the broader context of the entire Conditions for and Unfinished Work of Mourning series, what ultimately drew you to these particular sites—those of sorrow and distress—and why do you feel it is important to highlight moments of resilience and endurance? Particularly at this time?

DR: For me, I think the answer is in the last part of the question – “at this time” – which is always changing. And this of course makes me think of the often cited Robert Frank quote from his video Home Improvements where he says something to the effect of,

“I’m always looking outside, trying to look inside. Trying to find something that is true. But maybe nothing is really true, except what’s out there. And what’s out there is always changing.”

I’ve always connected with that idea from both a pragmatist and quasi-spiritual place, as that’s essentially what I’m constantly up to – responding to “what’s out there” and finding the most compelling exchanges generally originate from locations where the topography is imbued with a heaviness – as a palpable weight that may have to do with its history and past occurrences, or perhaps what is conjured when a space or scene leads us to recognize something within ourselves.

I find it necessary and valuable to give into our deepest despair and look at it closely, even ontologically, to figure out just what it is, what is its nature – in and of itself. I don’t necessarily think anything magical happens when we do this, but tolerating sorrow and distress through resilience keeps our attention, it requires intense amounts of physical and mental energy. I think of endurance as means of situating ourselves in time in order to be here – in the ever-elusive present – effectively, as this duration is a relentless cycle and not at all individual. This seems important right now, as we find ourselves weirdly isolated while collectively linked via a global pandemic punctuated with daily reminders of thin, shallow mindsets propagated by our current administration. As a productive way forward, I propose an embrace of radical despair.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025