Poland Week: Tomek Sikora: Rediscovered Images

Inaugurating Lenscratch’s focus on photographers of Poland this week is the work of Tomek Sikora who I had the distinct pleasure of initially meeting at the home of a mutual friend in Paris many years ago. Tomek rushed into my friend’s apartment after having just finished a multi-year photo project documenting all of the stations of the Paris metro system in a whimsical series that wryly captured the comings and goings of the Parisian transportation demi-monde. Subsequent encounters with him and the diversity of his work provided me with confirmation of his adage that “photography is my never-ending fun”. All you have to do is google his name or visit his website to realize that you have entered an unusual photographic realm of fantasy, humor, caprice and occasional moments of exquisite beauty. Hiding behind his comical self-portraits is a serious artist with a clear vision in each of the photographic projects he undertakes.

Tomek Sikora was born in Warsaw, Poland, of a painter mother and a sculptor father. In his twenties he travelled to Paris where he delved seriously into photography. Upon returning to Poland in 1971 he worked as a photojournalist and in 1979 he completed two major projects: “Album” and “Alice in Wonderland”. These two series depicting a surreal vision of the world were presented at the Biennale de Jeunesse in Paris at The Museum of Modern Art in the Pompidou Centre. From that point, Tomek exhibited extensively in Europe and the United States. In 1982 he moved to Australia where he established an advertising photography studio and continued working in the area of art photography. He returned to Poland in the 1990’s and currently lives in Warsaw. He has won many awards for creativity in photography and continues to exhibit worldwide while teaching at various photographic colleges in Warsaw. IG @ tomeksikora.eu

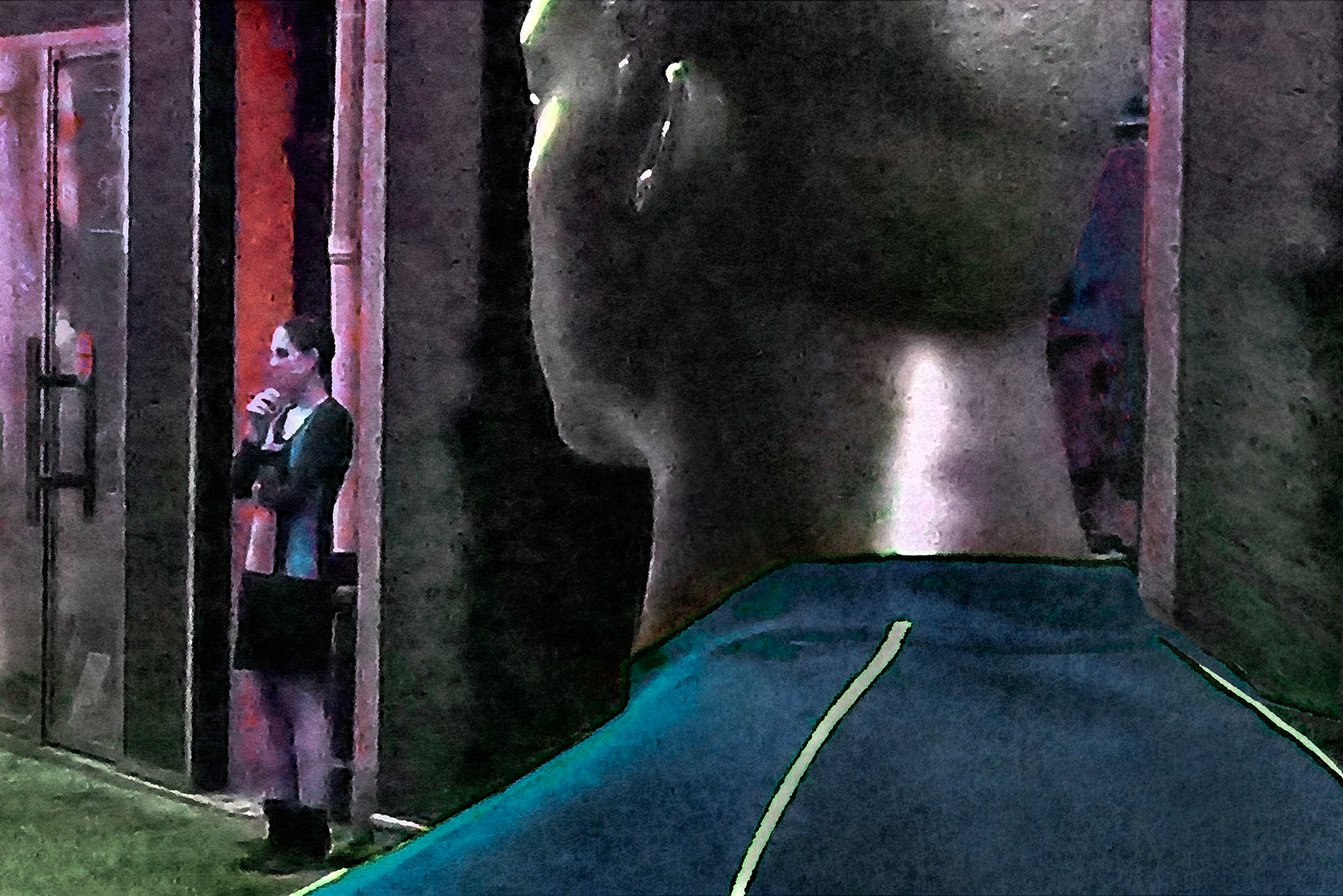

Rediscovered Images

“Photography captures reality. But does it do so objectively? After all we, the creators, decide which fragment of this reality to choose. By enclosing it in a rectangle or square frame, we give it a personal touch depriving it of a wider context. It is often the case that in the already cropped image we can rediscover small elements that can change the original narrative. Cutting them off from their context, not only do we get a new story, but by enlarging such a fragment of the photograph, we change its visual quality. An originally sharp image can be transformed into something totally different, a mere impression of the original. This transformation draws us into a different reality. It allows one to play with color and sharpness, the elements that cannot be altered in documentary photography.”

If I understand your project statement correctly for “Rediscovered Images”, you have taken small out-takes from previous photos and created an entirely new image from a portion of a larger image. After doing so, you have played with the “new” image with distortions of color, grain and other manipulations to create an almost painterly effect. What does this say about the truth or deception of a photograph?

At the beginning of my professional career, I worked as a photojournalist. Even then, it was difficult for me to accept the fact that the message of the photo depends mainly on the caption beneath it. Each journalistic photo is devoid of a broader context, so it can be read in different ways. For the past few years I have been constantly hunting with the camera in the streets. My goal is to capture interpersonal relations and those moments elusive to the eye that register reality like a film reel. A few years ago, while browsing through some of my photos from Aix-en-Provence, I noticed small fragments of an image that, taken out of context, created a new narrative. What fascinated me the most, however, was the change in image quality due to very enlarged pixels. Sometimes they resembled brush strokes or other painting techniques. I also realized that these works are the summary of my 50 years of photography. They combine two extremely different disciplines of photography: photo-journalism and created photography. I have been cultivating both alternately.

Given the extreme diversity of the work you have done as a photographer, how would you best describe your photographic style?

My philosophy is to play with photography, the limitless expansion of my oeuvre becomes the result of endless searching. The most important thing in this process is honesty and freedom from many rules. Each project is treated as if it were my first. I do not limit myself from either color or black and white, sharp or blurry images. The aesthetics are extremely important to me and this is where my searching leads.

Many of your photographic projects have elements of magical realism that you enhance by means of brilliant chroma, fantastical figures and a broad array of distorting techniques. Where do these fantasies originate?

Salvador Dali’s painting gave me the courage to materialize the ephemeral –surreal dreams in the form of arranged photos. Taking life seriously, especially under the communist system, would kill the remnants of an already enslaved imagination. This is what always gives us encouragement, the hope and desire to live.

Throughout your career your work has often dealt with childhood, children and the world viewed through the eyes of a child. They frequently seem to be contemporary fairy tales with humor and illusion. Is this your intention?

It is true. Children have a very selective way of looking at things. They mainly see what amuses them and what makes them laugh. In my experience as a father, my son Mateusz liked goofing around of older people the most. Hence my decision to create photographic illustrations for Alice in Wonderland with the participation of real people. At the Youth Biennale in Paris in 1980, I watched children’s reaction to these pictures. They were bursting with laughter.

Given the diversity of your photography, who have been the major influences on your work?

Definitely life and its diversity have been the only source of my inspiration. My projects are formally different because the variety of techniques emphasizes their character. Sometimes it turns out that my project is similar to something that has already been created. But don’t we, the creators, have the right to see the world similarly?

r

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Patricia Howard: Unknown AncestorsFebruary 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025