Craig Easton: Fisherwomen

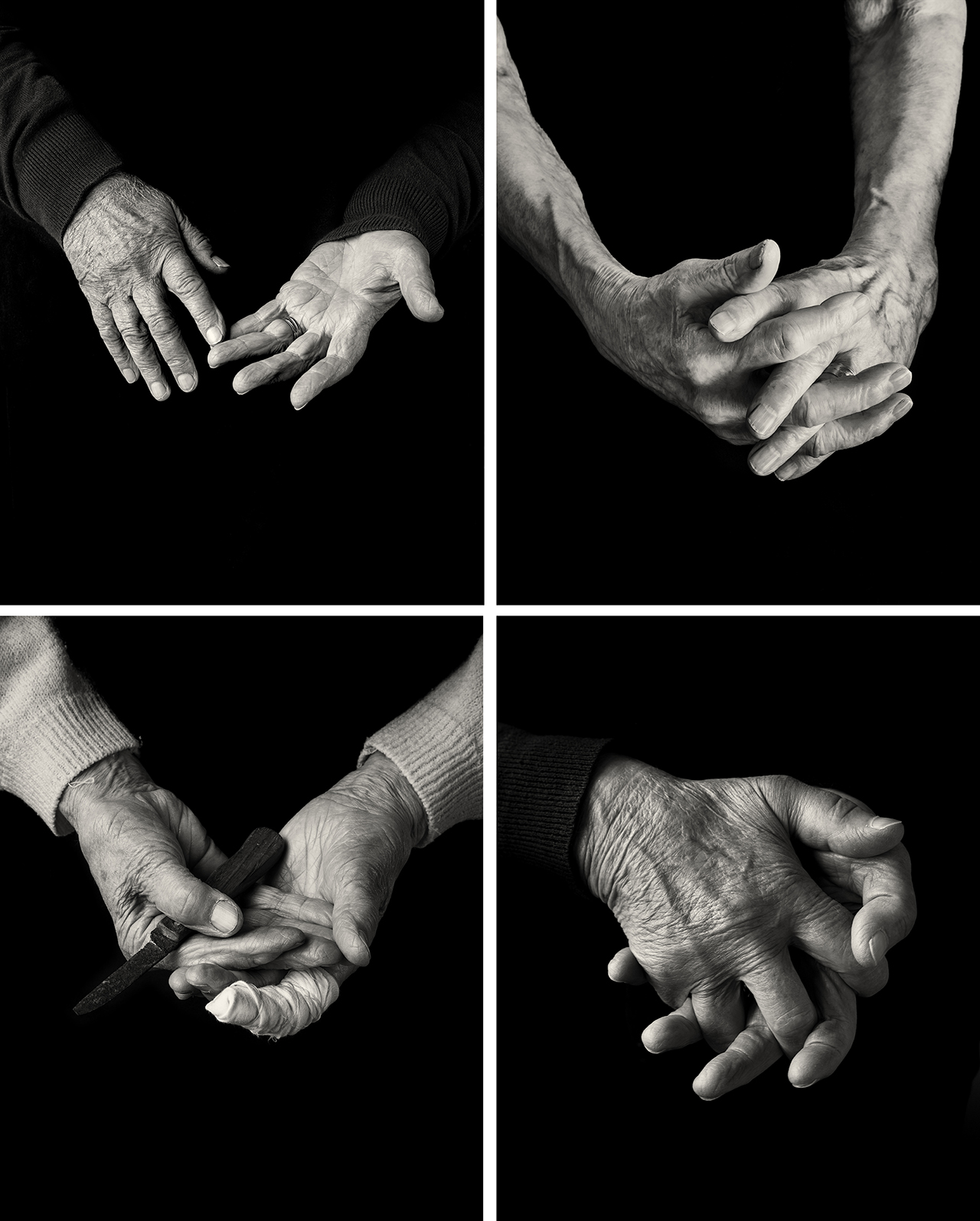

Craig Easton’s multi-year project, Fisherwomen, is a fascinating combination of portraiture, landscape and a touch of photographic iconography that harkens to past centuries yet feels exceedingly contemporary. Easton mines the visually rich milieu of the fisherwomen of Britain both in an historical context as well as with an updated view of a profession that has withstood the shifting mores of culture and industry. His brightly colored portraits of the women currently working behind the scenes as fisherwomen are juxtaposed with more somber head shots of women who came before them in the profession that he defines as “heritage”. The gnarled hands of the veteran retirees serve as symbols of a rough tradition that demanded much of these women as they traveled with the fishing fleets from the far north of Britain to a series of ports in the south. Easton captures this “Journey” in the third phase of his project with dramatic black & white landscapes that depict the various ports of call along the way.

FISHERWOMEN

Women have always played a critical role in the fishing industry. From the very early days they mended nets, gutted fish and baited lines, but they also did all the domestic work and raised the children. They even carried their men out to the fishing boats on their backs to ensure that they could go to sea in dry clothing.

Celebrated in the original calotype photographs of Hill & Adamson in Newhaven in the early 1840s and in the paintings of Winslow Homer, Isa & Robert Jobling, John McGhie and others from the 1880s to the 1920s, the fisherwomen of the British east coast were a common sight as they gutted and packed the herring into barrels on the bustling quaysides or carried the catch in baskets to sell door to door.

Today fisherwomen are no longer calling their wares on the quayside but are to be found mostly behind closed doors, working unseen in large fish processing factories, smokehouses and small family firms all around the coast. They are still fiercely proud of what they do. ‘I’ve never had a job like it.it’s constant banter. It’s piecework and I was one of the fastest gutters – it took me a couple of months to learn it and a year to pick up speed. My hand used to cramp up and I used to stab my finger all the time.’ Louise Hutchins

©Craig Easton, Paulina Efscynksa, shellfish processor, Stromness, Orkney, 2018, from the series: FISHERWOMEN

Heritage: The herring lassies are a unique phenomenon in the history of British women at work. A band of female-only migratory workers, who from 1860 onward left their families behind to follow the Scottish herring fleets to gut and salt-pickle the catch. The work was tough, the salt ate into their fingers, and they labored long hours outdoors in uncovered, unpaved yards surrounded by fish guts, but as workers they were fiercely respected, and the women valued their independence.

The tradition of ‘going to the herring’ was passed from mother to daughter for almost a hundred years and at its peak in 1913 as many as 6,000 herring girls would come to Shetland in early summer, staying in purpose-built gutters’ huts and working three to a crew: two gutters and one packer. The money was one thing, the camaraderie and freedom from parental control another with many older women remembering the time spent living in cheap lodgings and working long hours gutting and packing on the quayside as a ‘holiday’ despite the physical discomfort of bending down low over the farlan (the wooden trough the herring were tipped into) and the hazards of deep cuts from razor sharp knives.

‘At the end of the season, I set off from Lowestoft to London and I was there nearly three weeks. Oh dear, I fairly enjoyed that. I spent all my money. We’d had such a busy season; we were awfully well paid. I was at Simbister, one year, Lerwick two and then three and then four. And then I married. Silly me. I was twenty-two.’ Mary Williamson

You worked on the Fisherwomen project from 2013-2020. What was your initial inspiration in pursuing the project and how did it evolve over the seven-year time span?

I have worked in and around fishing communities for a long time and was aware of the great history of women in fishing from novels like Neil Gunn’s ‘The Silver Darlings’, the paintings of Winslow Homer, John McGhie and others and of course from the photographs of Hill & Adamson. Indeed, the Hill & Adamson calotypes of the Fisherwomen of Newhaven made in the early to mid 1840s are widely considered to be the first social documentary photographs ever made. So, I was aware of the representation of women in fishing and that in the past they had been the central characters of the paintings or photographs or novels and then it occurred to me that the portrayal of fishing in the last hundred years or so had been dominated by pictures and stories of men: the heroic guys going out to sea on trawlers to harvest the fish.

The project is divided into three segments: portraits, heritage and journey. How did you decide upon these distinctions and what does each segment represent? Why did you choose to separate the three segments instead of integrating them into a unified whole?

The heritage and journey sections are related insomuch as the landscapes are a visual representation of the journeys the herring lassies used to make. I felt that it was important to include reference to the landscape to acknowledge the long history of connection between all these places. Back in the days when the herring girls would travel to gut the fish, the people of Great Yarmouth would know of Whalsay in Shetland and Tynesiders would know Fraserburgh folk. Showing the landscapes helps a modern audience visualize the journeys and give a context to the places where the women came from and worked. And both of these sections of the project serve as the foundation for the contemporary portraits – they are there to very deliberately set the modern fisherwoman in the great tradition that goes back centuries. Many of the women nowadays didn’t necessarily know this history and when I told them about it and about my wider project, they were delighted to be carrying on such a tradition.

©Craig Easton, Edna Donaldson, herring bookkeeper, Great Yarmouth, 2019 (originally from Fraserburgh)

Why did you choose to shoot the portrait segment in color; the heritage segment in a combination of color and black & white; and the journey landscapes entirely in black & white?

Shooting the portraits in color was an easy choice… the places, the clothes and the characters are so colorful (not to mention the language which is colorful too!). I felt then that the portraits of the older women should also be in color – whilst they are no longer working at the fishing, they are of course still contemporary women, just a bit older, and so I didn’t want to make any distinction between them and the current workers. The series of hand studies are a kind of an outlier in the project to some extent – the opportunity was there to make these pictures to show the hard work that these hands had done and so whilst I only made a few of them, they feel to me like another layer – slightly more abstract than the main portraits and landscapes, but I hope an interesting addition to the wider project and an acknowledgment of the skill and nimbleness these old hands possess. (And of course, I am a great admirer of Paul Strand so it would be remiss of me not to acknowledge a debt to him and no doubt his work in South Uist was in the back of my mind when I made this work).

I made the landscapes in b&w just because I wanted to. I used to work a lot in black and white… and do again now, but this was my first work in monochrome for a number of years and I felt it was appropriate for the project. The idea with the landscape work is to be evocative of the landscape rather than always literal and so it is referring to journeys that happened for hundreds of years right up until the 1960 and whilst I shoot a lot of color landscape, it just felt right to make this series in b&w. I’m certainly not against mixing color and b&w in certain projects when the subject matter demands.

Most of your projects are documentary in nature with a strong emphasis on portraiture. What kind of research did you undertake in identifying the appropriate individuals to photograph? What problems, resistance or surprises did you encounter in your efforts?

I do a lot of research for all my work. It seems to me to be incumbent on serious photographers to have a thorough understanding of the subject matter they want to engage with. So, to that end, I read extensively about the history of the herring trade, about the women who travelled as herring girls both in fact and in fiction. I also looked at the visual representation of fisherwomen in painting and photography as mentioned above and I visited countless small-town museums along the coast. That was all the theoretical research, then on top of that were the hours and hours of conversations and interviews I did -some recorded, many not, and each one would add to my overall understanding of what I was trying to get across. I’m not sure I came across any ‘problems’ other than the usual issue that all this requires an investment of time and demands diligence… I find though, that if I am really interested in a subject then persistence pays off and one thing leads to another as the project evolves. I certainly encountered no resistance from the people I met who were all delighted that the spotlight was being shone back on the women in the industry, celebrating their role as it had been over hundred years ago.

©Craig Easton, The hands that gut the herring: Ruby Poulson,Whalsay, Shetland, 2018, The hands that gut the herring: Ruby Poulson, _Gut_The_Herring_x4 Whalsay, Shetland, 2018, rom the series: FISHERWOMEN

Journey: From the early part of the nineteenth century right up to the middle of the twentieth century, the herring fishery was one of the most important industries in Scotland. Each year as the shoals swam south through the North Sea, the fishermen of the herring fleet followed them. The east coast men began their journey in Shetland in the early summer and for the next six months sailed south bringing their catch into the fishing towns and villages down the length of the North Sea coast of the British Isles. The annual pilgrimage ended in the early winter at the English seaside resorts of Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft.

Whilst the fishermen travelled by sea, the fisherwomen mirrored their journey by land travelling from port-to-port gutting and packing the herring into barrels on the quaysides. The majority were Scots, but they were joined by women from the east coast of Ireland and a few from England, with special trains laid on to take the women south. Before the days of large factory ships with facilities to process the catch at sea, the connection between the fishing ports was tangible.

‘All the boats used to moor up, tie up at the weekend because the Scots fishermen, they never fished on a Sunday. The Englishmen did, but never the Scots. They all went to church with a Bible under their arm and sang hymns. They got drunk on Saturday, then went to church on Sunday to have their sins forgiven and then Monday they were all out at sea again.’- Edna Donaldson.

I was struck by the historical background that you cite as to the power and influence of women in the fishing industry who are relatively unsung –do you feel that the women you met working behind the scenes today have managed to maintain that sense of worth and accomplishment given their more repetitive tasks today?

I’m not sure that their roles are more repetitive – there was always some measure of repetitiveness in the job, but it is and always was a highly skilled occupation. To watch the women work, flashing a razor-sharp gutting knife with precision and speed is quite awe inspiring. In many cases the pay is for piecework – dependent on how many fish you fillet – and so speed and skill are of the essence. I found a great pride in the work they were doing, but each and every one of them when we talked about the history was conscious of how hidden the work is now as opposed to back in the day when it was performed outdoors on the quayside and the characters were celebrated in art and literature. I wanted to change that.

©Craig Easton, The remains of the gutter’s huts, Baltasound, Unst, Shetland, 2018, from the series: FISHERWOMEN

You have had a number of successes with this project and your more recent project, “Bank Top”. What do you have in store for the future?

I’m a documentary photographer and every day I see a greater and greater need for our society to be recorded – there are no shortage of stories to be told. Fisherwomen is slightly different perhaps to some of my more political work – it is very much a celebratory approach to a subject matter that I felt needed to be honored. The historical aspect to the project of course does tie in with much of my other work – Bank Top is very much focused on the representation of northern communities and how the legacy of colonialism and centuries of industrial policy have shaped modern society. Thatcher’s Children definitely aims to set the experience of inter-generational poverty in the context of social policy and so I do try to set my work in the context of history and make connections to wider concerns where appropriate. As before I have a number of simultaneous projects on the go, and we will be publishing a monograph of the Bank Top work this autumn. Exhibitions of that work and of Thatcher’s Children are in the pipeline and, of course, the Fisherwomen show continues to tour for the next couple of years at least.

Craig Easton is an international multi award-winning photographer whose work is deeply rooted in the documentary tradition. He shoots long-term documentary projects exploring issues around social policy, identity and a sense of place. Known for his intimate portraits and expansive landscapes, his work regularly combines these elements with reportage approaches to storytelling, often working collaboratively with others to incorporate words, pictures and audio in a research-based practice that weaves a narrative between contemporary experience and history.

A passionate believer in working collaboratively with others, Easton conceived and led the critically acclaimed SIXTEEN project with sixteen leading photographers exploring the hopes, ambitions and fears of sixteen-year-olds all around the UK. SIXTEEN was exhibited in over 20 exhibitions throughout 2019/2020 culminating in three simultaneous shows in London.

FISHERWOMEN, his long-form examination and celebration of women in the fishing industry has been exhibited widely in the UK and internationally. An exquisite large-format portfolio was published by Ten O’Clock Books in 2020 and in Easton’s continued belief in cross-disciplinary practice, the voice recordings he made in the field were presented as a highly acclaimed BBC Radio Four documentary.

In April 2021, he was awarded the prestigious title of ‘Photographer of the Year’ at the SONY World Photography Awards for his work Bank Top. A monograph of that work will be published by GOST books in 2021.

Easton is a regular visiting lecturer at universities and runs workshops internationally. His prints are widely collected and held in important museum collections in the UK and internationally.

FISHERWOMEN, a large format 24pp 11”x15” limited edition portfolio is available from www.tenoclockbooks.com

BANK TOP, Easton’s award-winning series from the SONY World Photography Awards 2021 is available to pre-order at www.craigeaston.com

Follow Craig on Instagram: @mrcraigeaston/

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

Julie Rae Powers: Deep RutsMarch 2nd, 2024

-

Interview with Peah Guilmoth: The Search for Beauty and EscapeFebruary 23rd, 2024

-

Interview with Kate Greene: Photographing What Is UnseenFebruary 20th, 2024