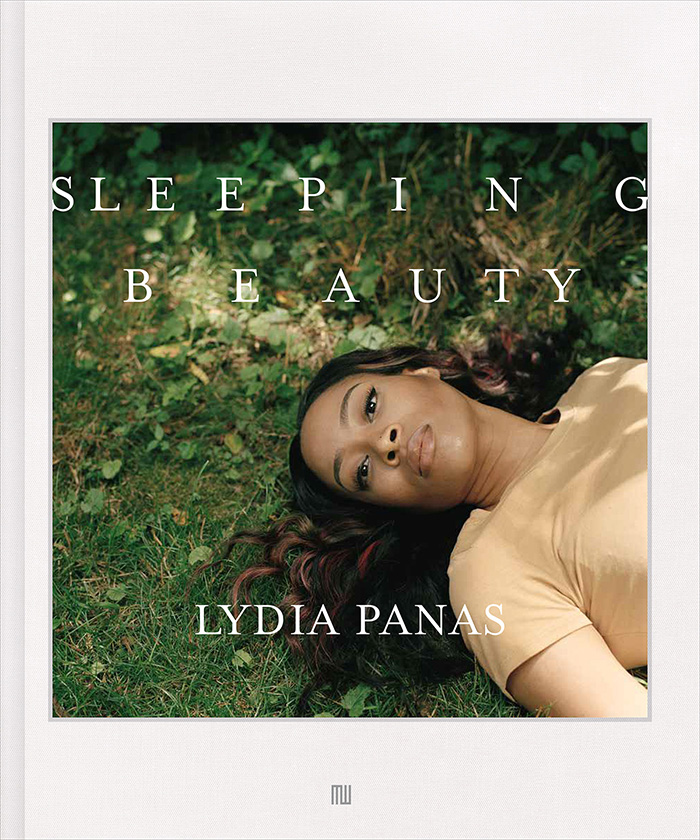

Lydia Panas: Sleeping Beauty

“While my subjects do in actuality turn their gaze towards me, it’s as if at times I turn the camera onto myself, both in the present and back in time.”

We are thrilled to share Lydia Panas‘ new monograph Sleeping Beauty, published by MW Editions. The book includes text by Marina Chao, Maggie Jones, and Monae Mallory. Adding to Panas’ extensive legacy that considers the psychology of women, Sleeping Beauty is a mesmerizing collection of the two-way female gaze. Her subjects are in a state of repose, but unlike the fairy tale character, they are fully engaged and awake, staring back at the camera and the woman behind it. Faces reveal a trust that they are in a safe space, and also that they are truly being seen, each with their own unique beauty. These analog photographs reclaim territories made by male artists over the centuries, but this time from a female perspective, allowing the subject to have a voice and connection, removed from objectification and sexuality. The book can be pre-ordered HERE.

An interview with the artist follows.

Lydia Panas is a visual artist working with photography and video. All her work is made in the fields, the forests, and the studio of her seventy-acre farm in Pennsylvania. The connection she feels to this land and her family is the foundation of her work.

Panas’ work has been published and exhibited worldwide including National Portrait Gallery (London), Scottish National Portrait Gallery (Edinburgh), Philips Collections (Washington D.C.), Artists Space (New York), Athens House of Photography, Corcoran Collection (Washington D.C.), Korean Cultural Center (Los Angeles), Kunstlerhaus Bethanien (Berlin), Museum of Modern Art (Tblisi), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO), The Print Center (Philadelphia), and Zendai Museum of Art (Shanghai). Her photographs are represented in public and private collections including the Brooklyn Museum, Bronx Museum, Museum of Fine Art Houston, Palm Springs Art Museum, Allentown Art Museum (PA), Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago, Museum of Photographic Arts San Diego, and the Sheldon Museum of Art (Lincoln), among others.

Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, the Village Voice, French Photo, and Hyperallergic, among other publications. Two monographs of her earlier work have been published, Falling from Grace (Conveyor Arts, 2016) and The Mark of Abel (Kehrer Verlag, 2012), which was named a best coffee table book by the Daily Beast. Her third monograph will be out in November 2021 by MW Editions.

Panas has degrees from Boston College, School of Visual Arts, and New York University/International Center of Photography. The recipient of a Whitney Museum Independent Study Fellowship and a CFEVA Fellowship, she has been an Artist-in-Residence at MASS MoCA, Banff Centre for the Arts, and a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome.

Sleeping Beauty

Exploring my unconscious and more emotional ways of experiencing the world, I consider what I longed for as a child, what I was afraid of, and the transformation from girl to woman. Looking through the lens, I reconfigure history and the relationship with my mother. But this time I’m holding the camera. Highlighting the importance of the past on the present and the inherently complicated relationship between artist and subject, I pay attention to the roles of power and trust. As I wander deep into my psyche, the process clarifies, brings me closer to myself, and suggests a sense of control.

“Sleeping Beauty” is about women, what we communicate and hold back from others, and our capacity for change. Working on the land where I live, the images articulate my own gaze through an intimate encounter with the models. The women act as a physical embodiment with the past, collectively, and individually. The serial nature of the poses and the setting reinforces the notion that the portraits are less about the individual and rather an impression, as each image builds successively upon the previous one. Straddling vulnerability, recognition, and resolve, the images draw the viewer into an intimate and uncomfortable encounter, dismantling the power of the viewing gaze.

My work builds on the history of portraiture and representation. However, rather than objectify or glorify women, I celebrate our contradictions and resilience. My camera does not look at women, it identifies with them. Attempting to photograph my subconscious is a means to connect with others. The space I create is distinctly feminine, vulnerable, and strong. This is my way to contextualize the female gaze, promote regenerative growth, and connect to something that feels both personal and universal.

Congratulations on your new book “Sleeping Beauty”! Before we dive into that, can you share the landscape of your earlier years and how you found your way to photography.

I’ve been interested in what motivates people since I was young. I was always curious about what they thought, why they said and did certain things. Making work has been a journey to understand things I felt as a girl that I needed to make sense of as a woman. A deep dive into my subconscious has given me insight and a way of reclaiming the garden, so to speak. I revisit forgotten, buried states of mind, the universal ones like love, belonging, abandonment. It’s an exploration to understand myself, others, everything.

Tell us a little about the book, the concept, design, how it came about?

The layout of the book, designed by Takaaki Matsumoto is clever. The placement of the text on the cover alludes to a dream state, and in contrast, the alphabetical order of the names incorporates a structural logic – order over chaos. Overall, the design suggests a book of fairy tales, but the content reverses the original tale, incorporating the perspective of a woman, and her determination to wake up or move forward on her own rather than wait for others to make it happen. More specifically, in contrast to the fairy tale her beauty is her inner strength, and the design combines the conceptual and psychological nature of the work, internal and external, chaos and order, asleep and awake.

My work has strongest impact when hung on the wall, in a band around the room where the life-size (and larger) women’s faces stare intently back at the viewer. The consistent, serial nature of the images works similarly in book form too – reminiscent of the Sugimoto seascapes, as a collective impression, rather than as individuals in the photographs.

The book was a long time coming and with the pandemic I wasn’t sure I should go ahead with it, but I’m glad it finally happened.

You have a long legacy of portraiture, but portraiture that is incredibly intimate and psychological. How did this way of working come about and why are you drawn to return to portraiture?

I love to make photographs of women, but I don’t necessarily see them as portraits. I’m interested more in relationships and what happens between us. I began years ago by taking pictures of my children, and even then, I did not feel the photographs depicted the kids as much as they depicted an idea I wanted to capture – something I wanted to say. I have come to understand that looking at someone face to face, sitting still so we really see one another is part of the motivation. Something happens when I watch someone through the lens – I don’t intend to document the subject in front of me, instead, to depict my inner reactions, an amalgam of my past as it interacts with the subject in front of me. It’s this stillness, this intimacy, this closeness, that I am exploring. Something happens in those moments that motivates me to click the shutter. I’m interested in what happens when we look without the noise. I don’t ask them to pose in a special way, to do something to please me, they can just be themselves. It’s a fascinating process where I feel completely connected with the model and with myself. I experience a power I don’t feel elsewhere. But it’s a democratic power where I feel like the ‘good mother’ who loves unconditionally and receives in return. Through the process, we both feel seen. We begin the photo sessions a little anxious and move on to a beautiful state of calm and connection. Portrait photography as a medium is inherently fraught with an uneven power structure. How people use power is something that interests me greatly, so the process is endlessly fascinating.

The work in Sleeping Beauty is focused on women and girls in a state of vulnerability and beautiful repose. Why did you want to photograph in this way?

The women and girls in these images are in vulnerable positions but they also look directly at the viewer, clear-eyed, skeptical, wary. I am trying to show them in an in-between state, moving into stronger versions of themselves. I had not thought of them so much in repose, I saw them more as in a state of vulnerability, but since you mention it, there is also serenity in knowing. I don’t intend to photograph a particular way but if it feels right, I go with it and let the work tell me what it wants to say.

That said, I am driven by the idea that appearances can be deceiving or that how something looks on the outside is not always how it is on the inside. How women/people extract themselves from oppressive psychological, social, cultural, and political systems which tend to be interconnected. My focus is on psychological illumination. You need to understand both the landscape and your underlying strengths before you can move forward. Progress isn’t easy, it’s usually slow, but it’s necessary, and it feels good.

Can you describe the multiple layers of meaning in the portraits?

It’s like the multiple layers in dreams. The literal meaning of the title ‘Sleeping Beauty” can refer to the fairy tale, though for me it signifies internal strength. A literal interpretation of an image could be a beautiful photograph of a woman lying on the ground. ‘Ground’ can have multiple meanings – grounded like a teenager who is punished, or the positive grounded, as in a justified idea. The models can be seen as vulnerable, or if you look closer at the faces, they can appear wary or guarded. A sleeping beauty can refer to someone’s external beauty, internal hidden strength, or the beauty of understanding and change. It’s about empathy. We need to look deeper than the surface to understand what motivates someone. I think this is what is lacking in most discourse today.

By representing women, are you in fact, representing yourself? Are you dismantling the power of the viewing gaze on a space that is free of sexuality and celebrating the person?

I am celebrating states of transformation, of understanding, of change. My portraits are stand-ins for me, I think all portraits are stand-ins for the artist at some level. Mine represent me at different moments in my life. They also consciously channel other people in my life as well. I feel like I turn the camera onto myself both in the present and back in time. The pictures in “Sleeping Beauty” depict a sense of conflict, both a confidence and a reserve. It’s an ambiguous, but strong viewing experience. Outwardly, the images are lush, green, beautifully arranged but when viewers look at these larger than life-size faces, they feel a sense of vague discomfort. “…The images are both at times difficult to approach and then…difficult to walk away from.” Compelled to interact with the women in the pictures the viewer feels as if the anticipated viewing experience has been reversed, and that they are being looked at.

I know that you work exclusively on the land where you live, which must add a comfort level to the projects. Can you tell us more about working specifically in the same place?

I think it adds a level of comfort to work that focuses on exploring discomfort. This land is the first place where I felt at home. I had a bi-cultural upbringing, and while it had its advantages it was also complicated and confusing. I felt neither Greek nor American. My father was raised on a farm in Greece and when I moved here, he, my husband, and I reforested the seventy-acre farm and brought both the home and the property back to life. I raised three children here and came into my own as a woman, a mother, and an artist. This land has been an important influence on my life and my work. It feels natural to work here as this place lends itself to notions of family, early relationships, and belonging. Watching people interact and watching my own interactions with others is more potent in this place. The comfort level I feel here gives me the freedom to summon my subconscious discomforts. The work is ultimately about personal growth over time and watching the untamed growth on the farm has been inspiring. The specifics of place are not important so the viewer can focus on the feeling, rather than extraneous information. My aim is to understand more about myself, about relationships, about the world. I think that we become artists because we have something we need to work out or say or understand, maybe a need to speak our own language, to find an authentic place in the conversation, especially if we come to find we don’t speak the same ‘language’ we were taught.

It was so wonderful to spend all of 2020 in conversation with your photographic legacy for the project Visual Conversations. I was struck by how many parallels we could find in our work, and I feel like I know you in such a deeper way by the sharing of images. We both began our careers photographing family and that focus has never wavered as you continue to explore familial relationships, identity, intimacy, and the relationship between the subject and the photographer. How do your children feel about the visual legacy you have created with them?

I adored working with you on the Visual Conversation and feel the same about you and your work. And the timing was great, a daily conversation where we were connecting across the country in a language that we could share but was also distinct to each of us. Relationships, family, women, identity, intimacy. I’ve always thought when someone works with their obsessions, it brings about the strongest results. My favorite quote by Miuccia Prada – “The exploration of who we are and what we want to become. Is there ever any other subject?” The closer to home, the more specific the topic, the more universal the work (a paraphrase of sorts from Lisette Model).

My children have not posed much since they were very young. They never really liked it. To be fair, looking back at my many binders of negatives from their childhood, they posed a lot more than I realized. A lot more. It’s only fair that they were not interested in it. And to be honest, I respected that about them. They take after me in this (defiance plays a large role in my work) and it made for good pictures.

I asked them your question via email, and they all agreed that as children, posing felt like a chore, something they didn’t understand, an interruption in their play. They found it uncomfortable (I think both physically and mentally), they didn’t like sitting still, holding ‘weird’ positions and props, not smiling. They also wrote, each in their own way, that as they have grown, and stopped posing, they have come to appreciate it. They said that with each new photograph and series, they gain a deeper understanding of who I am. Hearing me speak about it allows them to see the world the way I see it, broadens their perspective, and brings us closer (this brings tears to my eyes).

And

“…I believe she taught me an invaluable skill – to let go of the emotions and thoughts at the forefront of my mind that take over and be still for a second. This allows me to get a second perspective on myself in that moment and take a step back from the situation.”

This is what I want from viewers – to look at the work as a series, take a step back, and pay close attention to what you feel. Where are you in this?

Who is inspiring you lately?

I recently saw the Jennifer Packer show at the Whitney and was very inspired. Also the Diana Markosian film “Santa Barbara” at the ICP and a new book of short stories called “Daddy” by Emma Cline. With paint, film, or words, all three of these artists speak to the depth, the pain, and the beauty of the human condition in a luxurious and gorgeous way.

What’s next?

I am working on a new series of portraits in the woods that feels regenerative, and I am experimenting on connecting the portraits with still- lifes of flowers. I guess I’m going to keep working the way I always have and see where it takes me.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026