Contemporary Approaches in Historical Processes: Carmen Lizardo

©Carmen Lizardo, Portrait with Pearls, 2020 Dimensions: 36 x 24 x 2 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel.

How does modern alternative process differ from traditional uses of historical process? This week, all of the artists that we are featuring use historical processes with very contemporary approaches. Some of the artists alter the chemistry. Others combine their chosen process with other techniques, not only breaking the rules but opening up more possibilities to define contemporary alternative process.

Carmen Lizardo is a mixed media artist who uses alternative processes like gum printing, tintypes, and Kalitype printing which she then integrates with other elements like hair, paint, crystals, and gold leaf. Carmen’s work is not limited to historical processes; she also adopts other processes like screen printing and laser engraving and uses mediums like graphite or charcoal. All of these elements come together to tell intriguing stories about immigration, race, identity, gender, disabilities, politics, and history. Carmen’s imagery usually starts with a self-portrait that may be altered, but she might also use portraiture to alter a historical portrait as she does in the series Unidentified African American woman. The imagery is powerful because it does not let history or the past define Carmen Lizardo. She defines herself through her artwork.

©Carmen Lizardo, Portrait of Mami with red stripe, 2021 Dimensions: 24 x 24 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel

Carmen Lizardo was born in the Dominican Republic and immigrated to the U.S. at 19. She holds a BFA in Photography and an MFA in Digital Art from Pratt Institute. For Lizardo, using multiple media is an essential part of her work, particularly alternative photo processes, printmaking, drawing, and video work. Lizardo’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. She has received several awards, including a Women Studio Workshop Book Production Grant, a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship (nominated in both Painting and Photography), The Academy of Arts and Letters, and an Enfoco fellowship. Lizardo was one of five American Artists of Latino descent awarded an international travel and production grant from the U.S. Department of Cultural Affairs. Her works and process are included in two academic books: Gum Printing: A Step-by-Step Manual Highlighting Artists and Their Creative Practice (Focal Press) and The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes (Cengage Learning). Lizardo is a tenured faculty at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

Follow Carmen Lizardo on Instagram: @carmenlizardostudio

©Carmen Lizardo, Cracked, 2012 Dimensions: 24 x 36 x 2 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel.

Artist Statement

My artwork weaves personal stories and historical, political, and cultural heritages to speak about immigration, race, transmutation, memory, and identity. My work always begins as an Autobiographical/Auto-portrait experience and describes the human need to situate oneself in history, mainly the one belonging to the American Cultural Collective.

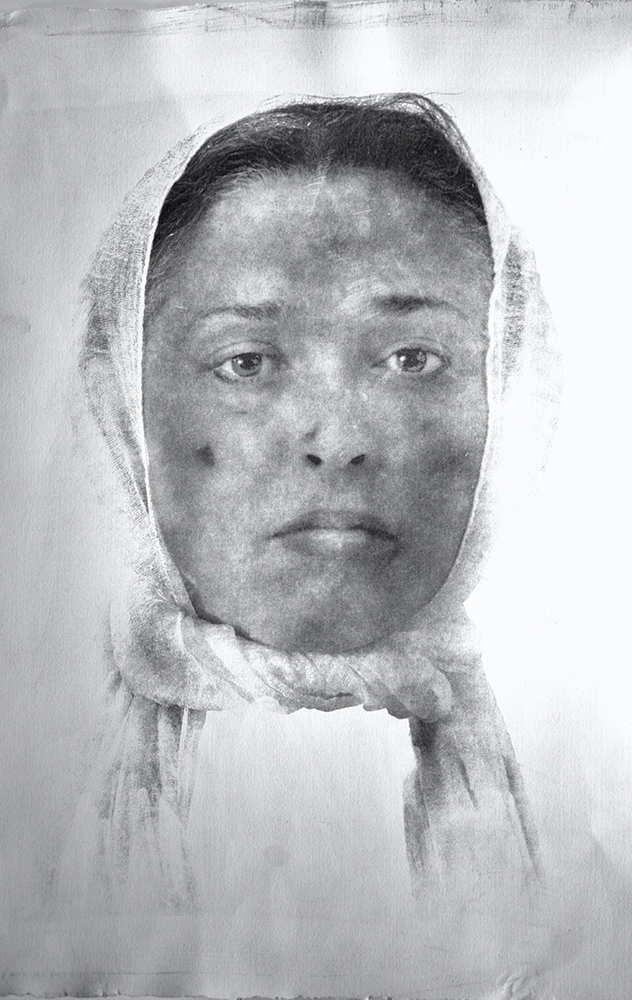

To Swallow a River

In the series To Swallow a River, I use the idea of bodies of water and portraits from public and personal archives and original photographs to explore the relationship between voluntary- involuntary immigration and their intersections with modern forms of slavery within American history. I use personal ancestral documents, photos, and library archives to find portraits of unknown African American women. These archives hold the visual record of hundreds of pictures of unknown Black people, mostly photographed at the turn of the Century. This work reinvents the stories obscured by white supremacy’s disenfranchisement of Black history by presenting a counterstory of conquest and beauty. One in which a new history begins with beauty and reverence for those not seen.

My process begins by creating temporary collages -projecting or copying the original pictures and “floating” them on different fabrics, wallpaper patterns, water, sand, or paint. I then photograph the temporary collages, printing them on transparent paper. The transformation of the image begins by using paint, gold leaf, and iridescent pigments on the backside of the print. These works become one-of-a-kind physical records of their previous ephemeral existence. They are transient through time and transmutation, their beginnings never to be seen by others, remaining as a private experience; their metamorphosis exists only in memory. The final images are unapologetically present, bringing those looked at but never seen.

©Carmen Lizardo, Portrait of an Unknown Woman, Through the Looking Glass, 2022 Dimensions: 24 x 36 x 2 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel.

Greg Banks: Talk about your childhood in the Dominican Republic and what led to you becoming an Artist?

Carmen Lizardo: I grew up in La Romana, on the Eastern side of the Island, and Sugar Caneland. I had little exposure to art growing up and no formal art training. I came to the US at the age of nineteen and fell in love with art after visiting the Metropolitan Museum for the first time. I knew then that art would be a forever journey for me.

©Carmen Lizardo, Self-Portrait with Silk Boat, 2021 Dimensions: 24 x 36 x 2 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel.

GB: How and why did you become interested in alternative or historic process?

CL: The narrative nature of my work is informed by the paintings of Vermeer, The drawing of Seurat, and the photography of Gertrude Käsebier and Julia Margaret Cameron. My art experience was shaped by Western Art models, which I learned to love while not being reflected in them as a woman of color. I stumbled upon a women’s pictorialist publication at the very beginning of my photography studies; I saw a Gertrude Käsebier, “The Heritage of Motherhood,” and I felt connected to the tactile qualities in the picture. I didn’t know what a gum print was. As I was learning the process, I realized I could draw with water, and that was my introduction to the world of thinking about photography as a means of obtaining an image without necessarily accepting the recorded photo.

©Carmen Lizardo, Portrait of an Unknow woman, 2021 Dimensions: 36 x 24 x 2 in. Medium: Pigment print with Gold leaf, paint, mica pigment, on panel.

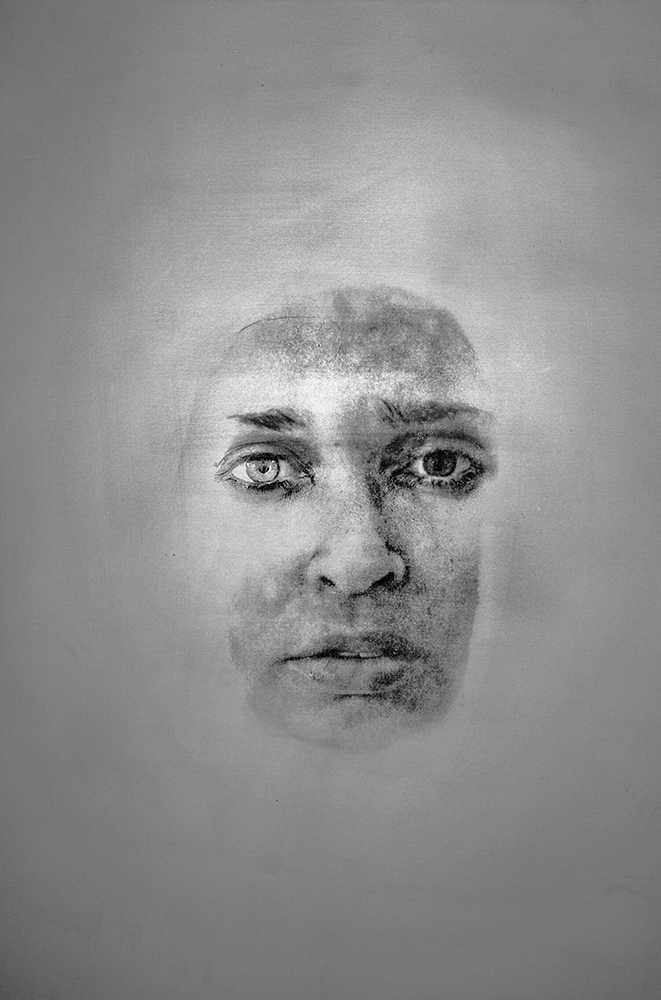

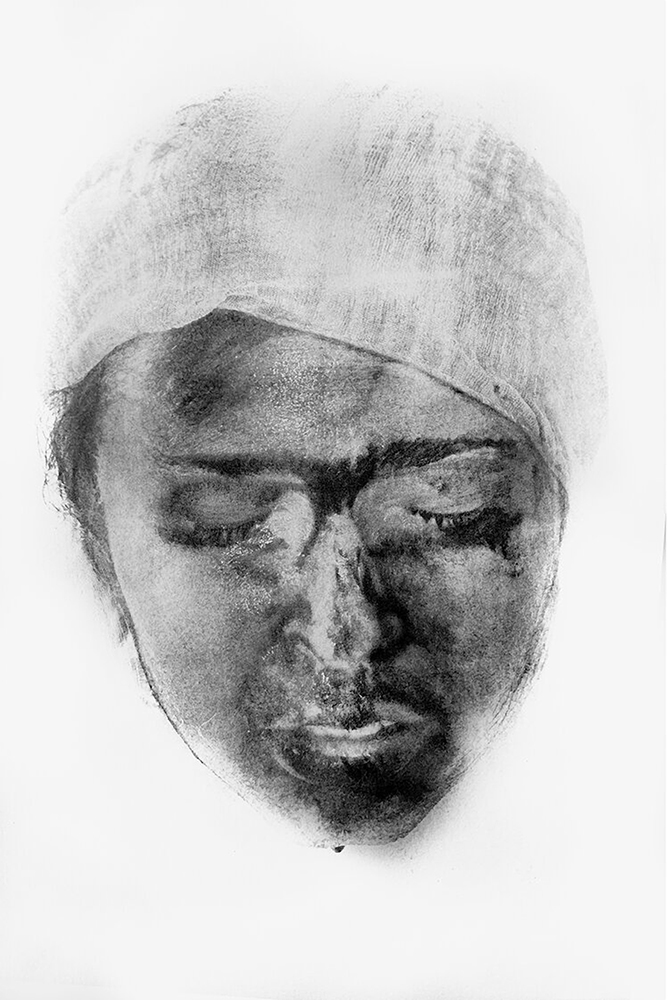

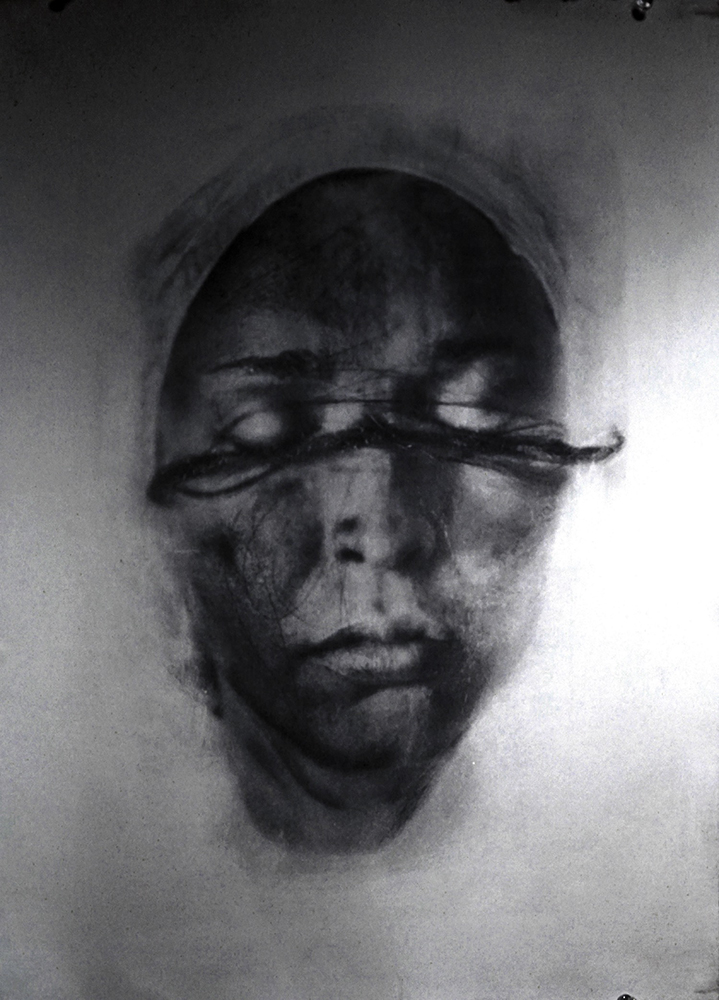

Yentl

Yentl describes how women’s physical and mental pain is discarded as emotional or pseudo-pain. This work describes my intersectional life experiences as a woman of color with disabilities—specifically, the tensions and issues of being a minority within a minority. The person’s identity gets fragmented, causing an internal conflict of placement and acceptance, a tug of war between defining oneself between social issues of race, and the stigma that comes with visible and invisible impairments.

GB: Talk more about your practice and why you combine many processes?

CL: I deconstruct the image’s identity through a series of often non-reversible steps while retaining the photograph’s ability to record and reinvent reality. For me, alternative photography provides a tangible image-making process, creating a balance with modern technologies. The beginning image is a sketch for the construction of my work. Using antiquarian techniques allows me to physically change the picture, often erasing the image and starting over on the same surface. I found that work emerges carrying an embedded visual history of the mark-making of how it was made. For me, painting, drawing, and photography commune with each other. I’ve never “taken” a photograph; I build them. l, consider materials and techniques, and experiment. Digital technology plays an essential part in the way I work. It pushes the boundaries of the physical process to a more surreal space which frees me to conceive new ways of creating imagery.

This allows me to behave as an alchemist of my medium.

GB: Tell us why you weave these historical, political, and cultural narratives in your work.

CL: I use my art as a cultural tool to affect social change: my work is my voice. The tool I use to inspire dialogue, action, and progress. It is a record of my refusal to accept the unacceptable.

In doing self-portraiture, I travel inward to show people what is happening on the outside.

GB: How do identity and place play a role in your work?

CL: Individuals’ identity is defined by external factors, demarcated by society and the environment that they are exposed to. Through generations, immigrants’ historical associations are directly affected by regionalism and displacement. My artwork creates a counterstory for those placed in the crack of invisibility between the worlds of being an immigrant and an emigrant at the same time, never appearing whole in the narrative of American History.

GB: What are your hopes for the work and how it effects the viewer?

CL: I aim to create work that speaks about truth and take that truth from a personal space to a public one. Our need to express ourselves becomes ever more urgent once we feel that freedom is in danger. My work recaptures the gaze and questions the unconscious bias between race and gender. It describes how society turns marginalized groups into objects within the system.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026