Contemporary Approaches in Historical Processes: Tasha Lewis

How does modern alternative process differ from traditional uses of historical process? This week, all of the artists that we are featuring use historical processes with very contemporary approaches. Some of the artists alter the chemistry. Others combine their chosen process with other techniques, not only breaking the rules but opening up more possibilities to define contemporary alternative process.

I first saw Tasha Lewis’s cyanotype sculptures in Christina Z. Anderson’s book Cyanotype: The Blueprint in Contemporary Practice. I remember thinking I had never seen anything like this work using cyanotype or any other process. I felt a shift in what was possible with the process. Tasha’s series of animal sculptures called The Herd are covered in fabric, mimicking skin, with cyanotype printed details on them that are stitched together. I began to search for more of Tasha’s work and discovered The Swarm, a collection of magnetic fabric cyanotype butterfly sculptures that Tasha attached to metal objects around her hometown, Indianapolis Indiana. The butterfly installations then began to show up in the places of Tasha’s travels. Finally, she began to collaborate with others around the world for a project and book called Swarm the World.

Tasha Lewis’s wide-ranging sculptural practice employs the body of the artist as a starting point for investigations into the interconnected histories of textile and technology, and the ways in which history’s multiple returns to the female form both empower and undercut her own influence in systems of power.

Her debut solo museum exhibition, Flood Lines, at the Parthenon Museum in Nashville, TN was on view from January through July of 2020. The body of work was profiled by the National Endowment for the Arts magazine as well as the Tri-Star Art’s Online video series, Liminal Space. The ombré dyed textile skins and bead encrusted bodies had previously been explored in her Ebb Tide and Full Fathom Five exhibitions at the Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens and the Sarasota Art Center. A wide range of Lewis’s work has been shown across the United States in group shows at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Spartanburg Art Museum, the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Sotheby’s Institute.

Lewis holds a Master of Fine Art from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and a Bachelors of Arts from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. Her academic study has consistently woven literature, theory and art history with her materially expansive visual art practice. She has been supported by professional development programs including The Artist-in-the-Marketplace at the Bronx Museum of Art in 2014 and Creative Capital, New Jersey in 2018.

Follow Tasha Lewis on Instagram: @tashalewisartist

©Tasha Lewis, Tidal Bather, Plaster, wood and mesh base covered in sewn cyanotype skin with macrame coral and beads, 2017

©Tasha Lewis, Tidal Bather (Detail), Plaster, wood and mesh base covered in sewn cyanotype skin with macrame coral and beads, 2017

In my practice I merge digital and analogue sculptural techniques with the icons of ancient history and tactile material reflections of my personal embodiment. My interests in art history, economics, philosophy and poetry position the objects born from my practice to be interrogators of ideals of beauty, the construction of gender-roles, and the devaluation of female-gendered labor. Following from Silvia Federici’s study Caliban and the Witch, I posit the Italian Renaissance as a turning point after which women were yoked into a wholly new construct of domestic labor. In response, I reprise neoclassical tropes: decorative columns, bathers, devotional paintings, and stretch upon their frameworks novel skins vibrating with the now. With my hands, textile takes many forms: it is cloth, skin, exposed warp and weft, and metaphorical matrix. – Tasha Lewis

©Tasha Lewis, The Swarm, ephemeral installation on the building facade of the Museum of Innocence, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014

Greg Banks: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became an artist? Also how did you discover the cyanotype process?

Tasha Lewis: I grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana and as I child I can remember always being encouraged to make things with my hands. My mother is also a photographer and when I was in middle school she gave me her Fujica SLR camera. I love shooting film. Soon after, my parents helped me set up a small darkroom in our basement’s utility room. I especially enjoyed pushing the boundaries with solarization, double exposures and collage, so when we found out about the Maine Media Workshop’s class for Young Alternative Process Photographers it seemed like the perfect fit for the summer before my senior year of High school.

Many cyanotype artists working today, myself among them, can trace their start to Brenton Hamilton. He is an amazing teacher, and that two-week workshop in 2007 was fundamental to my current art practice. Not only did I learn about the cyanotype process, but my interest in photographic layering and manipulation was encouraged. I later returned before my final year in college to be Brenton’s teaching assistant for another group of Alt-Pro Teens. I had just started making cyanotypes on cotton, and during that time in Rockport I made my first stuffed cyanotype piece: a small heron’s head and neck.

Back at Swarthmore College, I was building towards a senior art show in the List Gallery, and I ended up filling it entirely with fabric cyanotypes stitched around paper, cardboard and tape sculptures. From 2012 to the present, I use cyanotype variously for its powerful graphic and illusory qualities, for it’s amazing depth of color and contrast, and for its associations with humanity’s obsession with collection and preservation.

©Tasha Lewis, The Swarm, As part of solo exhibition “Moments of Thaw” at the Harrison Center in Indianapolis, Indiana, 2013

GB: Talk about Swarm the World and how it became a collaboration around the world?

TL: The Swarm began in the fall of 2011 after I realized the double-sided nature of cotton soaked in cyanotype chemicals. I made negative pouches which allowed me to expose registered images on both sides of the textile. I began with leaves, but butterflies soon followed. Like their counterparts in curiosity cabinets, these insects were pinned down behind glass, but instead of arranging them on orderly grid, I assembled them in swooping swarms. They were a subversive force pushing back against the taxonomic impulse.

I had already been working with neodymium magnets to make my sculptures appear to pass through Plexiglas planes or found glass objects, so it was a natural extension to stitch a single tiny magnet ring to the body of each butterfly. In the summer of 2012 I had 200. By the summer of 2014 I had 4,000. Each one was printed, developed, cut, stiffened, and sewn by me. In gallery installations before the Swarm the World project I used metal mesh or hanging wires to create an environment for the butterflies to occupy.

During those first few years, especially between 2012 and 2014, I was simultaneously installing ephemeral street art versions of the Swarm in Indianapolis, Chicago, Berkeley, Kona, Hilo, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Istanbul. It was during my trip to Turkey that I realized, after packing 250 butterflies in my suitcase, that I could entrust the swarm to others and thereby allow them to cover the globe in a way I could never do as an individual. Once I returned to New York, where I was living at the time, I built a website for the project, sketched out the idea and began to solicit applications. After the story was picked up by various online publications, I received hundreds of requests to participate.

I eventually selected about 120 participants in 45 different countries and on all seven continents (I had some scientists pick up the butterflies in New Zealand and take them to McMurdo Station in Antarctica.) The concept was that there would be numerous routes each with multiple participants who would send the butterflies along to one another after a few weeks. The installations would be documented and the images posted on our Tumblr site. The project launched in the fall of 2014 and did not finish until the fall of 2017 when I designed and self-published a book.

The project was logistically complex. I was often bogged down by import taxes, shipping delays, address changes and the constant common life interruptions we all experience multiplied by all of my participants. Butterflies were lost along the way, but what was gained was an amazing collaborative creation. Placing the butterflies requires metal, so I encouraged my participants to seek out the human-made artifacts in nature and to bring the natural world into their urban spaces. The swarm can highlight a landscape or cover an unassuming object to give it new life. Creative solutions abounded as participants sought to highlight their town, or country’s particular beauty.

©Tasha Lewis, The Swarm, As part of solo exhibition “Blue Butterflies: Migrations Across America,” at The Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, Columbus, Ohio, 2014

GB: You are known as a sculptor, why are you drawn to photographic process in your practice?

TL: In the arc of my art practice, it was photography that came first, and in many ways it was the specific nature of cyanotype which led me to be a sculptor. I have always been interested in layering, both in the physical materials and in the conceptual citations in my work, so in many ways it was my desire to add even more depth to my photographs that I began to create them in three-dimensions. Since 2018, my practice has enfolded even more textile techniques like fiber-reactive dye, beading, weaving, braiding, net-making, digital embroidery, macrame, and laser-cut appliqué. These have variously empowered me to speak more specifically through cloth about women’s devalued labor and the intertwined nature of textile and technology.

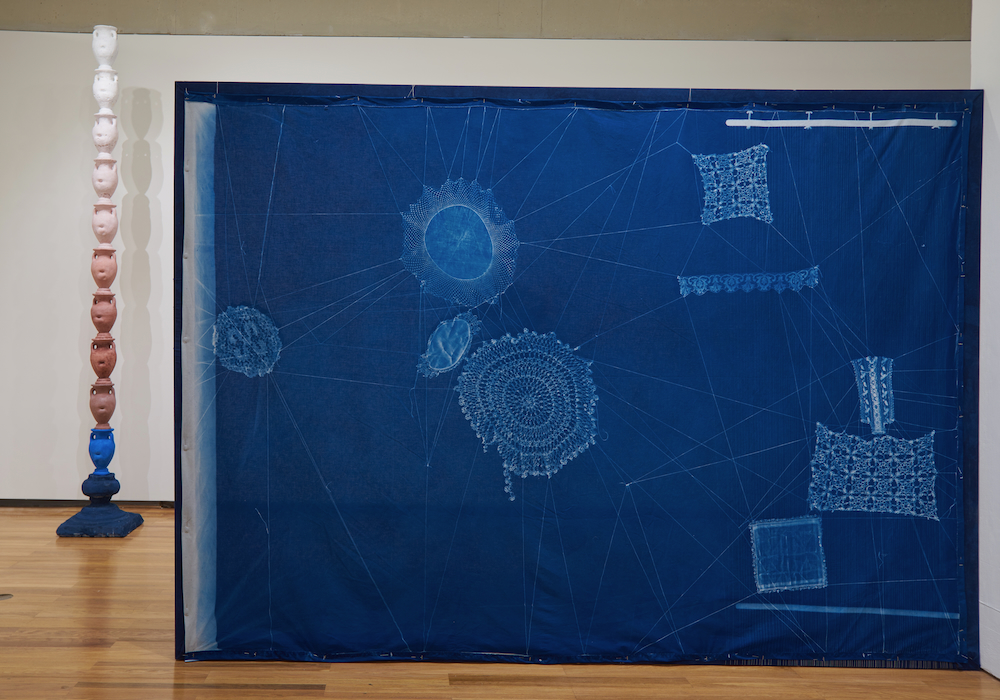

In graduate school I learned to be a metal fabricator, mold-maker and caster. The more immovable materials of steel, plaster, concrete and porcelain became compliments to hand-marbled textiles, laser-cut Plexiglas lacework, and life-cast latex elements. Yet in my show “The Offerings” a key element was a huge cyanotype print stretched across a frame containing the objects of the negative. “Lacework and Its Image” as I called it, embodies the core of my investigation with cyanotype. It challenges hierarchies by presenting viewers with a double sided meditation on textile heirlooms paired with their cyanotype image. Both sides have an aura of their making, and neither feels dominant over the other. The presentness of the cyanotype exposure blooms with the immense labor built into the tatted pieces by my great-great-Grandmother. This cyanotype is also immense and architectural. It hold space as well as time.

[http://www.tashalewis.info/1offerings.html]

This piece also embodies one of my favorite parts of the process: the way in which it can be opened up to collaboration. The culmination of the Maine Media Workshops class was often making a cyanotype mural with the bodies of the students, found materials or fabricated cardboard cutouts. This practice is re-born in “Lacework and Its Image” as the scale necessitated a communal effort to help me expose and develop such a large image. Further, I see the creation of the negative from textile heirlooms as particularly primed to be open to a site-specific social practice where community members could build a web of textile with me which would result in a unique cyanotype record.

All this to say, cyanotype remains foundational to my multi-media sculptural practice.

GB: I first saw your botanical beast sculptures in Christina Z Anderson’s Book Cyanotype: The Blueprint in Contemporary Practice. As a Photographer, they felt like something I had never seen before with the process. As a sculptor did it feel that way for you?

TL: It does feel novel and very exciting. The hybridity of the work means I am always engaging across artistic communities. Some see my works and instantly recognize the cyanotype, others are more drawn in by the sculptural forms and may not even realize that the surface is both hand-sewn and photographic in nature. As an artist I am driven toward the balance of novelty and historical dialogue. My practice is highly developed within the ecosystem of my studio, but it is also reliant on the contexts of other artists who keep the cyanotype medium alive.

GB: How would you describe your work conceptually?

TL: Cyanotype has served many different roles in the conceptual matrix of my sculptures. Initially I was interested in a direct dialog with artist scientists like Anna Atkins. My cyanotypes of natural creatures reflected that impulse to collect and try to contain nature in archive-based institutions, while simultaneously showcasing the unstoppable force of nature to subvert our expectations, as in Swarm the World. Indeed, perhaps subversion is the through-line as I developed as an artist.

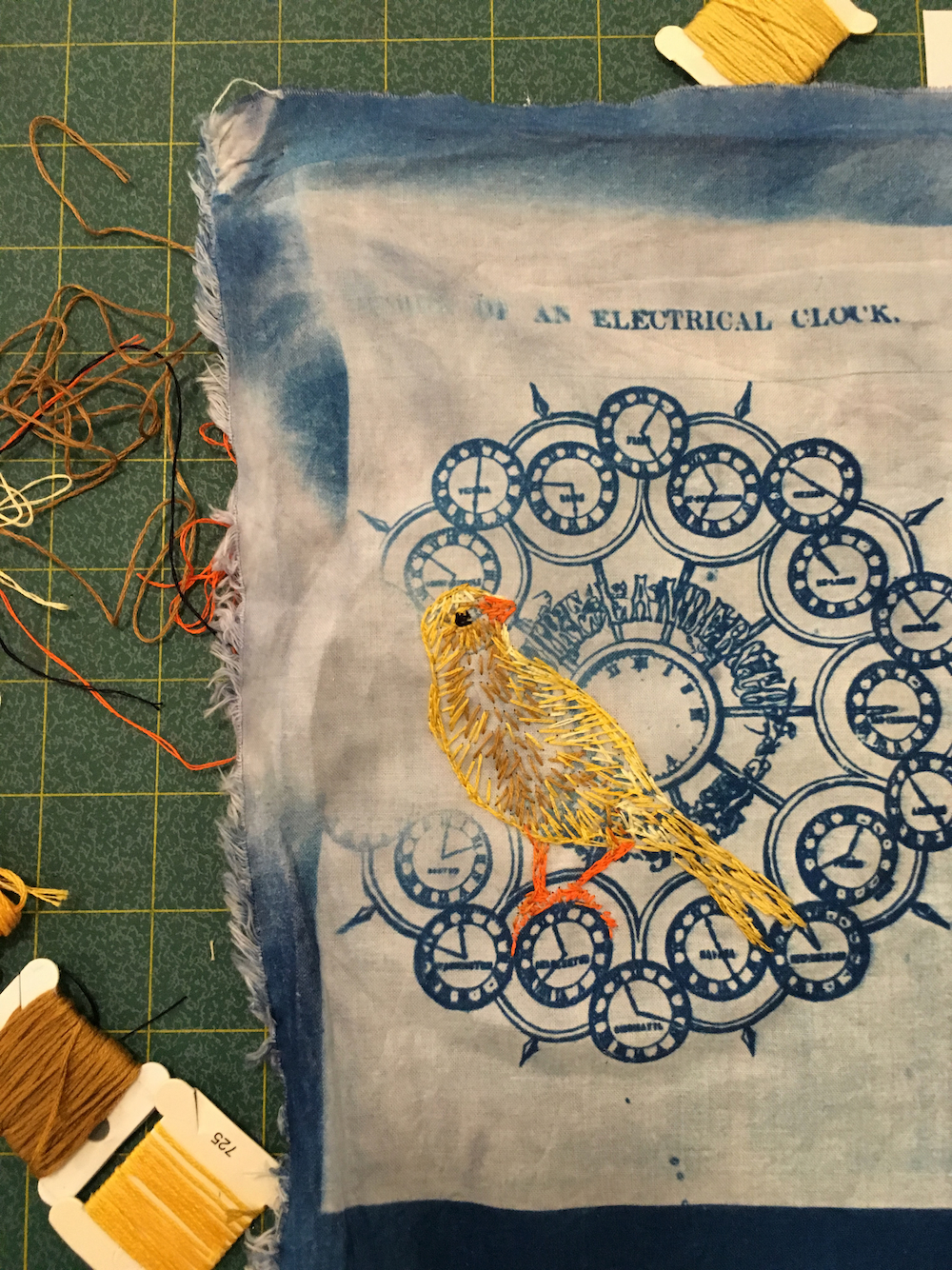

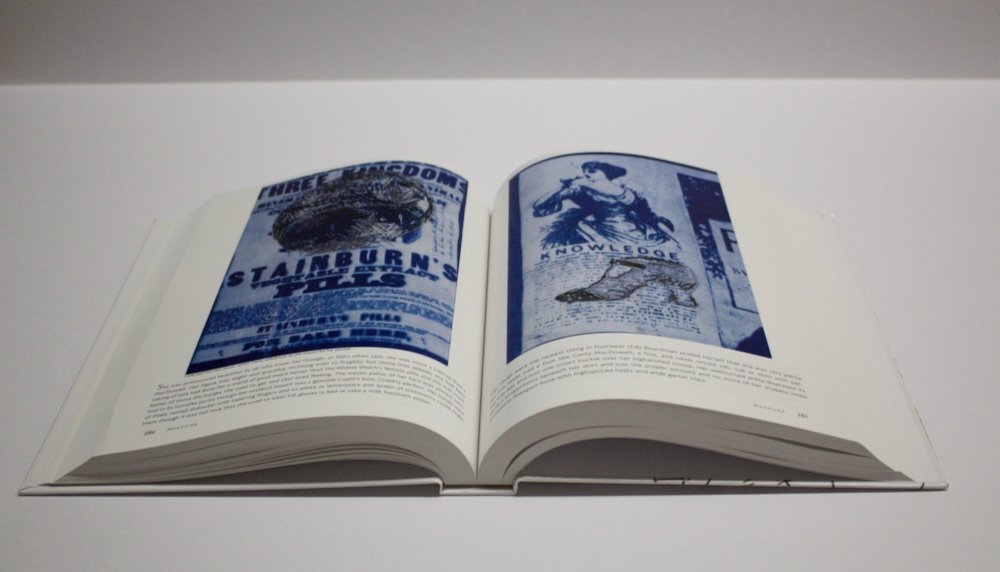

In my book arts project to illustrate ever page of James Joyce’s Ulysses, I made cyanotypes of advertisements for the chapter Nausicaa which were then embroidered. This section of the novel is defined by consumerism, both Gerty’s female saccharine view of products and Bloom’s voyeuristic view of her. Accordingly, I gathered historic ads as the visual foundation for this chapter. The embroidered stitch represents variously the floral touches in Gerty’s language or the geometric lines of Bloom’s gaze. [http://illustratingulysses.com/Chapters/13nausicaa/Pages/p284.html]

Tidal Bather I & II were not the first figurative sculptures I made covered in a cyanotype skin, but they are the first made with casts from my body. In these, the cyanotype was printed from a cheese cloth negative to create a meta-textile. The warp and weft of the image is looser than that of the actual cotton and the play with scale draws the viewers eye in closer. The shift in color density on the prints moves from deep blue to pale lavender-white echoing the traces of a tide. The cyanotype provides not only the illusion of textile traces, but a chronicle a dynamic cycle of absorption and release. This cyanotype body was its own kind of archive: one of the experience of female bodies under the male gaze.

©Tasha Lewis, Lacework and Its Image (Verso), Wood, dyed textile, thread, great-great-Grandmother’s lacework, cyanotype, t-pins, 2022

©Tasha Lewis, Lacework and Its Image (Cyanotype), Wood, dyed textile, thread, great-great-Grandmother’s lacework, cyanotype, t-pins, 2022

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026