2023 Month of Photography Denver Reviews

Every two years, Denver becomes a photo destination filled with dozens of exhibitions, lectures, and opportunities through the Month of Photography Denver. Founded in 2004 by Denver-based artist Mark Sink, the festival has become an important platform for photography in the Rocky Mountain region, with works by hundreds of local, national, and international artists on display. The next festival will take place March 1-31, 2025.

The festival is presented by the Colorado Photographic Arts Center (CPAC), a nonprofit organization dedicated to fostering the understanding and appreciation of excellent photography through year-round exhibitions, education, and community outreach. Participating spaces include museums, galleries, universities, community art centers, nonprofit organizations, public spaces, businesses and other venues. Most events will take place in the Denver Metro area, with a smaller number of events outside the city in Boulder, Longmont, Fort Collins, and other areas.

At the heart of the event are the Month of Photography Portfolio Reviews, hosted by the Colorado Photographic Arts Center (CPAC). Executive Director Samantha Johnston and her capable staff create a two-day in-person event that includes about 30 significant people in the field of photography, including museum curators, gallery owners, publishers, collectors, and other industry leaders from Colorado and the United States. Photographers come from all over the country to share their work with reviewers.

Today, I feature three photographers and bodies of work that were wonderful examples of photographic storytelling, each with a unique perspective and approach.

First up, Patricia Howard‘s poignant project, Where You Come From is Gone. The artist combines new capture, thread, and photographs from family home movies printed on rice paper to speak to the fragility of memory. Connecting two moments in time, past and present, mirror the idea that we hold both of these memories at the same time. And what we consider the present, has already passed into the past.

Patricia Howard is an artist and photographer based in Louisville, Colorado. Her work often focuses on the concepts of family, home and memory. Her solo exhibit House to House at Photoworks at Glen Echo National Park, was deemed one of “The Ten Best DC Photography Exhibits and Photographic Images of 2019” by Louis Jacobson of the Washington City Paper. Her work is in the permanent collection of Juniata College Museum of Art, Colorado Photographic Arts Center and others. She has had residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, the Burren College of Art in Ireland and with the Photographers’ Master Retreat in France. Her work has been featured on the Don’t Take Pictures platform and exhibited at the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria, VA., Rathfarnum Castle in Dublin, Ireland; Redline Arts Center; Site: Brooklyn in New York, and many others. She currently teaches remotely for the Smithsonian Associates in Washington, DC. Patricia received an MFA in photography from Penn State University.

Instagram @patriciahoward154

Where You Come From is Gone

where you thought you were going to was never there,

and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it

Flannery O’Connor, Wiseblood

Where You Come From is Gone is a photographic series focusing on memory, home and family.

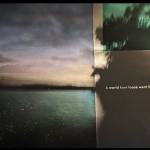

These images were created during a return to a childhood home after years away. There are photographs of a yard filled with buttercups, a metal lunchbox and the front door. There are glimpses of elderly inhabitants eating a tv dinner or feet up in the La-Z-Boy. Superimposed are frames from home movies shot years ago, often in the same physical space. The movie frames have been printed onto a semi-transparent paper, allowing the viewer to visualize both the past and the present. The movie images capture a moment from the past – a woman caught in the wind or the face of a long-gone grandmother.

How accurate is memory? Where You Come From has scenes that may or may not have taken place. There are images of the people who inhabited this place but are gone, the ghosts of the past. Some pieces juxtapose a person in the present with that same person in the past. There are still lives with family objects. The photograph and the movie frame are physically joined by embroidery. The lines of the stitches provide a 3-dimensionality as well as a bridge between the two images creating an appearance similar to the sprocket holes on film.

This house is a time capsule. I recently spent more than a year at my childhood home, with my widowed father, photographing the house, the surroundings, and the people. It was a time filled with uncertainty about the future and a place that can’t exist as it is forever. The time spent there was an opportunity to revisit and recreate a sense of the sorrow and the joy that make up a family. – Patricia Howard

It was such a pleasure meeting San Francisco photographer Jason Hendardy. Like his work, his persona sits in a space of honesty and humility. He is connected to the work he makes, with a background that included skateboarding, touring in bands, and making home movies. He has an ability to see the overlooked and understand the human condition. His project, All That You Say Can Be True, looks at America with all it’s flaws and inconsistencies, yet still hold a particular beauty.

Jason Hendardy is a photographer and filmmaker from the San Francisco Bay Area who currently calls Seattle, WA their home. The photographs and videos he makes searches for serendipitous moments and narratives that portray life as we experience it. He is deeply fascinated by the ways in which we interpret time and the impact that human activity has on the world.

Instagram @jasonhendardy

All That You Say Can Be True looks at my childhood memory of an American dream. The photographs are a collection of found moments that interpret beauty and opportunity in the overlooked. The series is inspired by my parents’ hope while immigrating to the US and my childhood optimism as a first-generation American but met with the understanding of the reality of existing as an adult in our current times.

Alexander Heilner has a long legacy of considering the environment and it was a pleasure to see him and his new project, Draining the Colorado, at the reviews. He approaches his subject matter with an acute sensitivity to the human impact on the earth and uses his stunning photographs to call attention to the earth in crisis. He states bout this series, “increased demands on the river, coupled with a twenty-three year megadrought induced by global warming, have led to a looming environmental crisis as the entire annual flow of the Colorado River Basin is now over-allocated, and the river is literally running dry before it reaches the sea.” His work is important and also disturbing.

©Alexander Heilner, Receding Waters, Lake Mead, Arizona / 2021 Lake Mead on May 23, 2021. Two days later, the lake fell below 1,075 feet mean elevation, which subsequently triggered mandatory cuts to water allocations for 2022, mostly affecting Arizona farmers. But the lake dropped another 30 feet last year, threatening more drastic cuts to water supplies across the West. Lake Mead is the nation’s largest reservoir, and serves as a critical point of control for the Colorado River. The dramatic reduction of inflow to Lake Mead is the result of a 22-year megadrought, as well as increased demands for Colorado River water both up- and downstream from Hoover Dam.

Alexander Heilner is a multi-disciplinary artist and photographer whose work inhabits both fine art and documentary initiatives as he investigates the relationship between artificial and natural elements within the environment, and within our culture. A winner of the prestigious Baker Artist Prize, Alex has exhibited, screened, and performed his work nationally and internationally, from the walls of MoMA to the catacombs of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. International photography festivals including Pingyao, Sienna, and Daegu have featured his aerial photography and he has been awarded numerous grants and commissions in support of his ongoing environmental projects.

Alex is presently engaged in two long-term endeavors which document radical shifts in our physical and social landscapes due to climate change. Draining the Colorado catalogs the diminishment of water throughout the Colorado River Basin; while The New Arctic examines the imminent and rapid changes occurring in Arctic coastal communities. For over a decade, Alex has also been photographing the elaborate campsites that serve as “home” for citizens of Black Rock City, the temporary desert metropolis built each summer for Burning Man.

Alex’ editorial and fine art work has been featured in National Geographic, Politico, The Guardian, The Chronicle of Higher Education, JPG, Details; myriad websites including Wired, Ain’t-Bad, Business Insider, and Design Taxi; and he has produced numerous photo essays for public radio’s Marketplace. Nearly 200 of Alex’ photographs are featured in the Encyclopedia of New York City, published in 2010. Alex was commissioned by Johns Hopkins Hospital to create digital collages which are featured throughout its complex and Baltimore magazine named him the city’s best photographer in 2012.

Alex earned his B.A. at Princeton University and his M.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts in New York. He has been teaching photography at MICA / The Maryland Institute College of Art since 2003, and served as MICA’s Associate Dean for Design and Media Studies from 2011 to 2018. Previously, Alex taught photography and digital imaging at NYU, as well as film and video production at SVA. He has also served as the director of the photography program at the JCC in Manhattan.

Instagram: @aheilner

©Alexander Heilner, Receding Waters at Lone Rock, Lake Powell, Utah / 2021 This photograph was made in May of 2021, when Lake Powell’s water level had dropped to its lowest level since it was filled in the 1960s. This drying has been due largely to a 22-year drought throughout the Colorado River Basin. After 2021, the reservoir dropped another 50 feet. As of November 2022, it was less than 25% full and continuing to drain. One could hike to Lone Rock without getting wet, as it was connected to the shore. Heavy winter snowfall in 2023 means that the lake is rising again right now, but this is likely a short spike in a long-term downward trend.

Draining the Colorado

I am engaged in a long-term effort to document the drastic changes occurring along the Colorado River; throughout its watershed; and within the communities that rely on its water for their lives and livelihoods. The Colorado River is in trouble. For hundreds of years, the river has been the lifeblood of the American Southwest, a region that is largely open desert, as well as dry plains, and

mountainous forests. The river’s basin drains about 11% of the present-day United States, and at the same time delivers water to about 40 million people living (mostly) in the same area. But increased demands on the river, coupled with a twenty-three year megadrought induced by global warming, have led to a looming environmental crisis as the entire annual flow of the Colorado River Basin is now over-allocated, and the river is literally running dry before it reaches the sea.

These images are part of a long-term project documenting the Colorado River’s use for agriculture, industry, recreation, and municipal consumption. Visually mapping the diminishment of the Colorado is a project I hope will serve two purposes. First, I hope to engender smart decisions about water use in the near future. But I also see this project as a decidedly aesthetic record, for posterity, of how this natural resource was managed and mis-managed in my lifetime. Global warming is changing lands we take for granted right before our eyes, and the better we understand these shifts and our role in them, the better equipped we will be to reckon with them.

©Alexander Heilner, Receding Waters at Scorup Canyon, Lake Powell, Utah / 2022 Lake Powell’s water level has been steadily dropping for 20 years, forcing recreational boaters and hikers to reconsider the contours of the reservoir on a regular basis. Just last year, the majority of this image would have been filled with water, flowing throughout the irregular rock formations in the lower part of the frame.

©Alexander Heilner, Las Vegas, Nevada / 2016 Located in the heart of the Mojave Desert, Las Vegas has been one of the fastest growing cities in America for decades. Its very existence would be unthinkable without the nearby Colorado River, which supplies nearly all of the city’s municipal water. With the river’s annual flow steadily declining, city leaders see the writing on the wall, and in 2021 passed a bipartisan law banning unnecessary grass from the city. While there are significant exceptions for private homes, parks, and golf courses, officials nonetheless expect to tear up 8 square miles worth of turf from medians and shopping centers, cutting water usage by 15%.

©Alexander Heilner, New Housing Development, Henderson, Nevada / 2021 Henderson, Nevada, along with much of the Las Vegas area, continues to add new housing at a rapid pace despite critically low water levels in the region’s reservoirs. There are currently no water-related restrictions on new development in the area.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2023 in the Rear View MirrorDecember 31st, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Staff Favorite ThingsDecember 30th, 2023

-

Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCullohDecember 17th, 2023

-

Black Women Photographers : Community At The CoreNovember 16th, 2023