Photographers on Photographers: Sara Bennett in Conversation with Chantal Heijnen

This spring, I met Chantal Heijnen, a photographer from the Netherlands living in New York City at the artists’ Preview Day for the New York Now: Home exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York. We were signing copies of the catalog created for the exhibition, and I was seated next to her 8-year-old son, Lou, who was also signing the books. At first I thought Lou was just helping Chantal, but I discovered that the two of them had collaborated on a series, “Lou’s Summer.”

I was drawn to Chantal, in part because she radiates calm and a certain centerdness, and in part because she’s a former social worker and I’m a former criminal attorney, and both of our artistic practices are informed by our earlier careers.

As I started to dig into Chantal’s work, I was struck by the tenderness of her photos, by the deep connection she has forged with the people she photographs, and by the absolute beauty of her images. I couldn’t wait to interview her for Lenscratch and to learn more about her, her work, and her thoughts on collaboration.

Chantal Heijnen (1976, The Netherlands) is a visual storyteller who uses photography to build connections on both sides of the lens. She holds a BA in Social Work and Photography. Her career as a social worker greatly informs her observant and collaborative approach to imagemaking. Chantal is also an educator. She teaches teen programs at the International Center of Photography, and in New York City shelters with Lantern Community Services where she uses photography as a tool to work with New Yorkers in shelters who are impacted by or threatened with homelessness.

Chantal’s documentary and portrait work has been published in international newspapers and magazines, such as The New York Times, Washington Post, LA Times, Stern Magazine, and Vrij Nederland. She has been exhibited internationally at LagosPhoto Festival, FotoFestival Naarden, FOAM, Bronx Documentary Center, Andrew Freedman Home and Photoville. She self-published two books ‘Ghost Republic Somaliland’ in 2012 and ‘Lou’s Summer’ in 2021, which is part of the Inaugural Photography Triennial at Museum of the City of New York.

Follow Chantal Heijnen on Instagram: @chantalheijnen

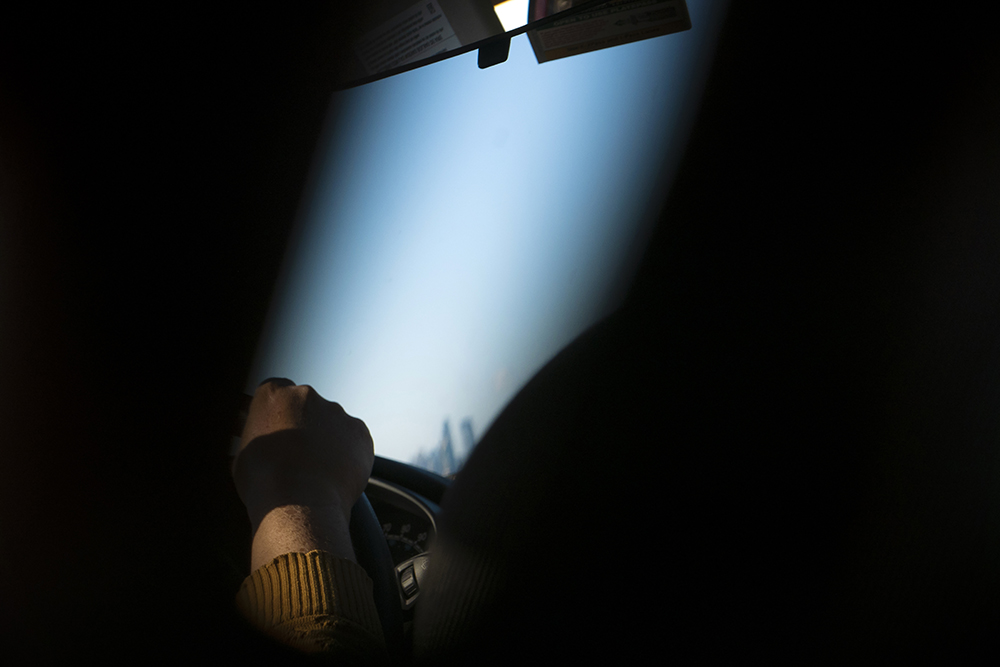

Lou van Melik (2014, NYC) first picked up a camera during the lockdown in 2020. He just turned 6 years old. While observing the empty streets of NYC from the back seat of the rental car Lou started taking photos, intuitively and unassuming. Just one click and done. Sean Corcoran, Curator of Prints and Photographs Museum of the City of New York, called it a “wide-eye perspective of a child”. During the car rides Lou loved to listen to his favorite song Blinding Lights from The Weeknd. Music inspired him while photographing and this album became the soundtrack to his lockdown experience.

Aaasssyyyrr a.k.a Aseed is a multilingual veteran and resident of Coney Island Beach. When he photographs, mostly in the dark of night, he wants to capture the specific feeling he was experiencing in the moment. “The pictures have a ghost-feel. They call it the witching hour, it happens around 12 o’clock at night,” he says. “I want people to enjoy the different sceneries of the beauty and the beach, but also a rendition of being in an environment where you are either sunburned or your body aches to the point where you can get frost bitten.”

Sara Bennett: It’s pretty amazing to see a 6-year-old’s photos hanging on the wall at a major museum. Can you tell me how that came about and what does it mean that the project is collaborative?

Chantal Heijnen: Thank you so much Sara! My son, Lou, turned 6 at the beginning of the lockdown. School stopped, we were at home like everyone else. We didn’t feel safe commuting on the subway so we decided to rent a car to escape our small NYC apartment. My husband Bart, who is a year-round outdoor swimmer wanted to keep swimming so we ventured out to Orchard Beach and Coney Island, short trips to get some fresh air and cope with our uncertainty.

And Lou started to see New York City in a different way, seeing an empty city from a car’s perspective. . He was very intrigued but bored and the same time. He wanted to do something and asked me if he could use one of my older a camera’s. I gave him a Lumix, an automatic point and shoot with a zoom and he started taking pictures. In the beginning, I didn’t think a lot about it.

I was the one driving and I could hear him clicking on the backseat of our rental car. I remember saying, “Lou everything is zoomed in, are you sure you’re getting anything” and he said he was. After a few weeks his card was full, and when I looked at the photos I was surprised and loved his intuitive photos with interesting perspectives. In June we went to the Netherlands for our yearly summer break and I was photographing Lou a lot. I started putting my pictures and his next to each other and that’s how we came to a collaboration. We self-published Lou’s Summer in the Netherlands. The Rijksmuseum bought the book for their collection and we are very excited to be included at the Photography Triennial “New York Now – Home” at the Museum of the City of New York

SB: Did Lou have a say over which photos you put in the book?

CH: I made the first edit. After that he picked the ones he liked best and I didn’t use any that he didn’t want. I wanted him to be proud of the book so he would be comfortable showing it to his friends as well. So I left out some photos that I probably would have used if I didn’t collaborate with him.

SB: I know you’ve been doing collaborative projects for a long time. Can you tell me about your first one?

CH: My first collaborative project is Ghost Republic Somaliland. When I was a social work refugee counselor, I met Fatma, who became one of my closest friends and she was always telling me about her homeland, Somaliland, an independent country within Somalia. Somaliland has never been recognized by the UN, even though they have their own passport, their own money, their own government. Fatma asked me to go with her and photograph the country she was born in and proud of. We went two times for a month, meeting and documenting the nation builders of a nation that officially doesn’t exist

The Somaliland newspaper ‘Jamhuuriya’ published my photographs twice a week – a total of 20 publications that symbolizes the 20th anniversary of Somaliland on May 18th, 2011. My first published book, with an edition of 90, includes the 20 original newspapers – a physical testimony of a Ghost Republic with essays by the editor of the newspaper and Fatma.

I believe that was the beginning of my first collaboration. ,It was important to me that it wouldn’t be only my take on the story, but also the perspective by the people most affected as well.

SB: People say my work is collaborative but I’m not so sure. As Richard Avedon said of portrait photography, “I used to think that it was a collaboration, that it was something that happened as a result of what the subject wanted to project and what the photographer wanted to photograph. I no longer think it is that at all. The photographer has complete control, the issue is a moral one and it is complicated.” And I do think it’s complicated.

CH: Well I love the way you add in the people’s handwriting and so that makes them very present in your work.

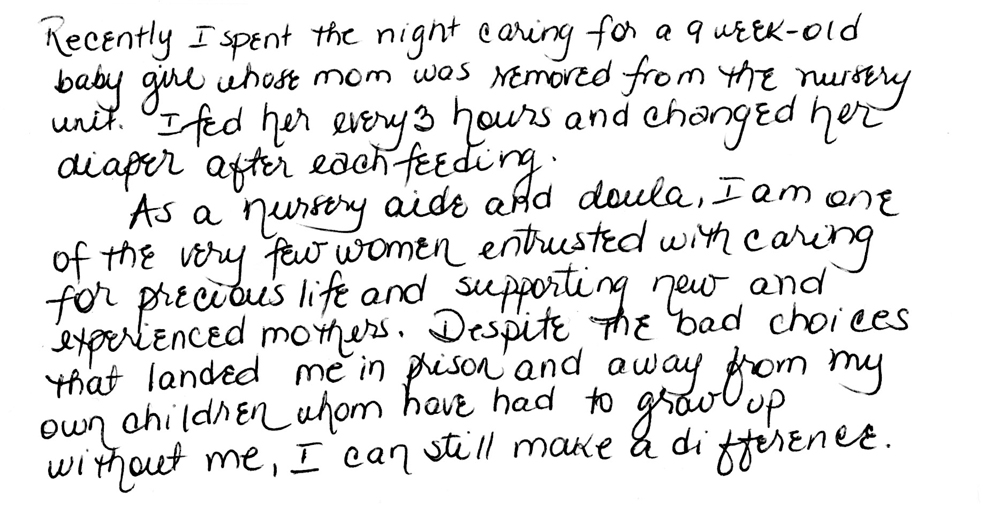

SB: Yes, I try to give the people I photograph a platform by incorporating their handwriting. But I would think it’s truly collaborative if we came up with the concept together, I photographed only what they wanted me to show, and they had complete control over the editing process.

CH: Yes you’re right, that would even be more of an equal collaboration. But I do think, that by combining both qualities, your portraits – approved by them, and their own personal messages, makes it in a true collaboration.

I think that your background as a former criminal attorney and my background as a social worker make us aware of the power dynamics there are if you work with people. For me it is very important to keep these dynamics and my privileges in mind while working on my photography projects.

The first few years, working as a photographer my biggest struggle was that I sometimes felt that I was only ‘taking’ from people. As a social worker it felt more giving. Therefor I found it hard to introduce myself as a photographer. That has changed over the years, as I see myself more and more as a storyteller creating photo documents of people that hopefully reach the viewers heart. For now, I feel I can do this best, by collaborating and incorporating the perspective from the people I photograph. This can be done in different ways, depending on what fits best to that particular project.

SB: Same for me. As a former attorney, I know the message I’m trying to convey about the criminal legal system, but I want to be sure the women’s own voices are present in the work as well. In the beginning, I interviewed them and every photograph was accompanied by their quotes. Then I decided to ask them for their own handwritten statements and put them on the prints themselves, which I think was ultimately more effective.

CH: I think that was a perfect decision! The work is so strong. The handwritten statements really helps to share their message even better. And it’s such an important story to tell. I’m glad the women wanted to collaborate with you and share their stories with the world.

SB: Thanks, I appreciate that!

CH: My real first collaborative project where the people I photographed started to photograph themselves was for Lantern Community Services, an organization dedicated to working with people who are impacted by or threatened with homelessness.

I’d been teaching photography classes there for 6 years and at the end of every year we would have an exhibition. The year before COVID the organization asked me to take official portraits of the workshop participants.. I photographed them in their home and they took pictures of what home meant to them. We made diptychs and presented it together during the exhibition. It was beautiful to see how empowering this experience was.

SB: I also teach photography—to women who live in permanent supportive housing. That sounds like such a good idea for an exhibition. Maybe I’ll do that, too, if they’ll allow me into their homes. Or if they’d allow each other into their homes, I’d have them take portraits of each other.

SB: Can you tell me about your project with Aseed, “The Sea is My Home,” which I think is an incredible example of a true collaboration, even if the initial idea came from you.

CH: I met Aaasssyyyrr, aka Aseed, who lives on the beach at Coney Island, through my husband Bart, who goes there for his daily swim. Bart told me about Aseed and thought I should meet him. So one day I went and I met Aseed. We started talking and I was intrigued by the way he was living.

At that time, I was nominated for the Somfy Photography Award and I had to create work on the theme of Home. So I asked Aseed if I could photograph him because the beach was, as he calls it, his humble abode. So he said, “Sure! I think it’s important to share the story of how I live on the beach.” I started visiting and photographing him a couple of times a week for more than a year and it is still ongoing.

He told me: “I was born on a navy ship to a Mongolian-Japanese mom and a Portuguese-Saudi Arabian dad. So the sea is my home.” Aseed served most of his life as a Navy SEAL, which gave him the survival skills to live outside year-round. “Having no comfort is comforting. These seven layers of clothing are my house: they shelter me from the malice intent in the world.” He started living on the beach during COVID, preferring the outdoors to the shelters, which were overcrowded and didn’t feel safe.

Aseed told me he was interested in taking photos as well and he started taking cellphone photos, but his phone and other items kept on getting “beached,” which means broken. I gave him the underwater camera I had been using because it’s weather-sealed.

Aseed is mostly interested in photographing at night when he’s all by himself. The day pictures I take of him are of how people encounter him at the beach and his photos show his inner world. Together it’s a complete body of work that shows not only my view but his view as well. It’s such an honor working with him on this project.

SB: Is Aseed involved in the editing process?

CH: I download the memory cards and make a first edit before showing him the photos.He the chooses what he likes best and then I edit from there. I ask him what the photos mean to him and I write down his quotes. He doesn’t want to be bothered too much with it so he wants me to mostly choose. He sees the photos I’ve taken of him. If there’s one he doesn’t like, I won’t use it.

SB: How does your social work background come into play?

CH: I think that being empathic is an important skill that you learn as a social worker. If I photograph people I try to understand another person’s experience and their point of view. I hope this understanding reflects in the portraits I make.

It is important for me that people are comfortable while I photograph them. I never push people to do anything they don’t want to do. .

While working as a social worker, I learned that you can get a lot of extra information by going to people’s homes – you get a better picture of the person you are working with. Therefor I’m drawn a lot to environmental portraits.

SB: Do you consider yourself an art photographer?

CH: I consider myself a portrait and documentary photographer. Besides the content, aesthetics are also important to me. I love photography and can’t get enough of images. Being able to create work myself is such a joy, especially if I’m being able to co-create with other people. I love to have a close connection with the person I photograph. I really want to bond with them. That’s what I love about all of your series. You can sense that bond and it makesyour work incredibly powerful and moving.

Thank you so much!

SB: And thank you for taking the time to talk with me. I really appreciate it.

After 18 years as a public defender, Sara Bennett turned her attention to photographing women with life sentences, both inside and outside prison. Her work has been widely exhibited in solo shows, including at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR, Photoville in Brooklyn, NY, and Rotterdam Photo 2023, and in group shows, including the Blanton Museum of Art’s Day Jobs, MoMA PS1’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration and the Museum of the City of New York’s New York Now: Home. Her work has been featured in such publications as The New York Times, The New Yorker Photo Booth, and Variety & Rolling Stone’s American (In)Justice. Her entire portfolio can be seen at sarabennett.org.

Follow Sara Bennett on Instagram: @sarabennettbrooklyn

@Sara Bennett, ASSIA, 38, in her room in her aunt’s house one year after her release from prison. Panama City, Panama (2022) Dream: A series of thoughts, images, and sensations occurring in a person’s mind during sleep. This is what I see when I look around my bedroom, a sacred space, which holds my secrets, fears, hopes, and desires. I can’t, nor do I want to wake up. This, my reality I cultivated for 17 long years, and today I’ve found it.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Leonor Jurado in Conversation with Jessica HaysApril 18th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Sarah Knobel in Conversation with Jamie HouseApril 17th, 2024