Photographers on Photographers: Sara Bennett in Conversation with Chantal Zakari

Aline Smithson asked me to review Pictures from the Outside, Chantal Zakari’s newest book in which she asked thirteen incarcerated men for specific instructions on a place they would like her to make a photograph. I told Aline that reviewing isn’t my forte but I’d love to interview Chantal for Photographers on Photographers. Once I got a copy of the book, though, I was sorry I wasn’t reviewing it, so here’s my very short review.

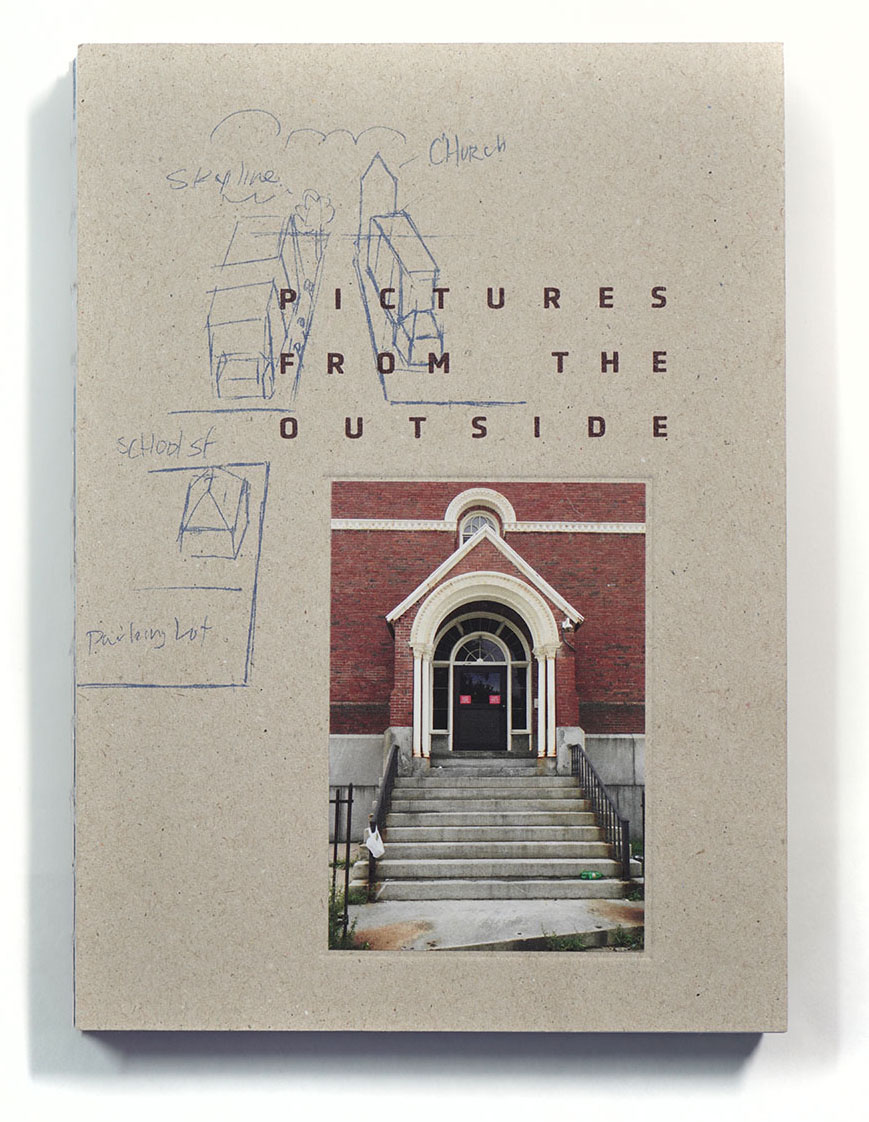

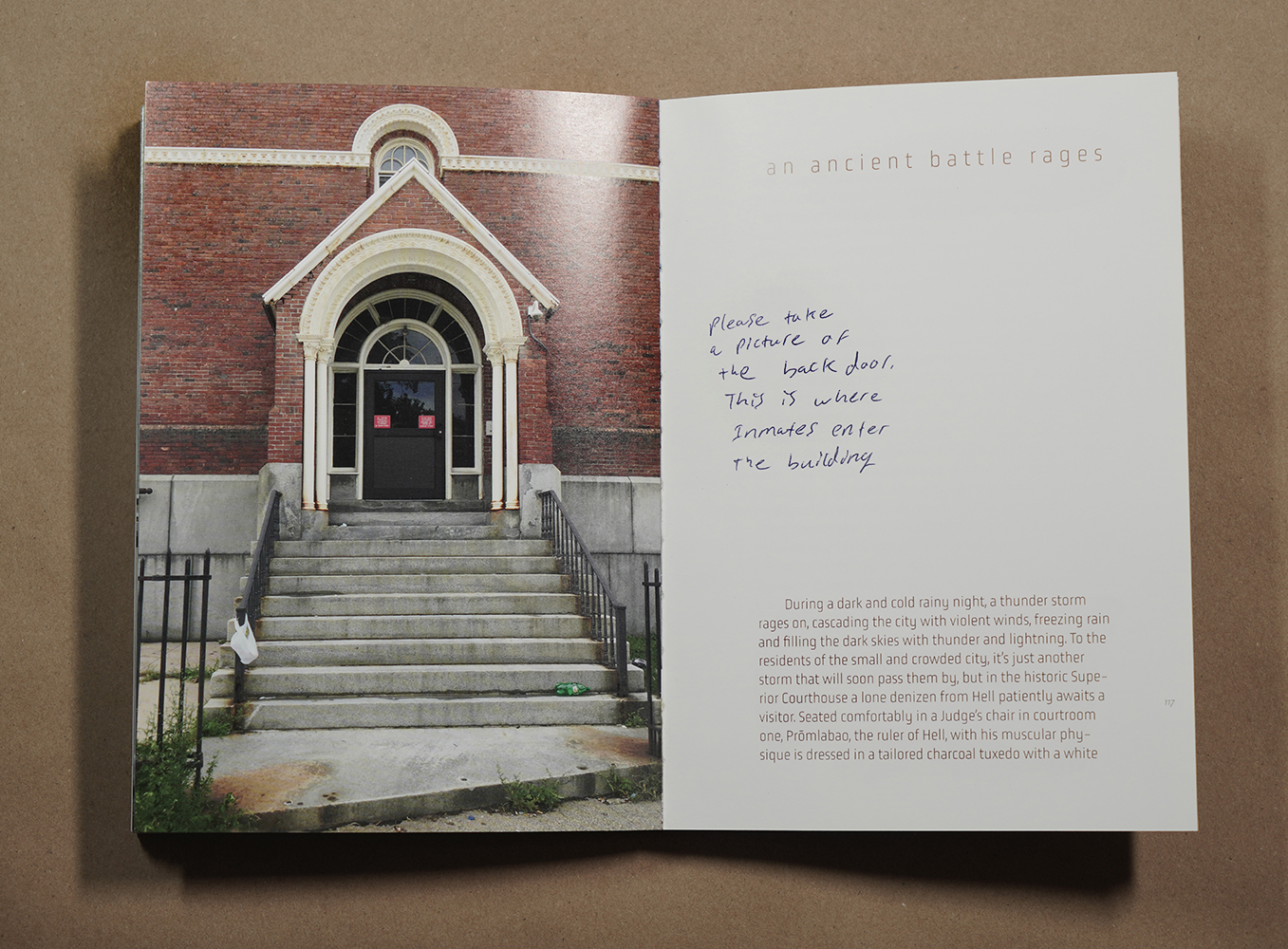

This is an artist book with a capital A. The physical form is beautiful and the concept is a brilliant collaboration between Chantal and the incarcerated men. Each photo conjures the men behind the requests, their vulnerability, openness, resilience, and wisdom. I spent a lot of time with each photo and read every word of the text. I was enamored from the moment I held the book in my hand; I love the open-spine binding, the chipboard cover with a photograph of the back of the courthouse door, a hand- drawn map of where she was to take a photograph, and a request for a photo of “the sky on a moonless night, where there are BILLIONS of visible stars.”

Chantal Zakari is an interdisciplinary artist, designer and art educator. In her work, she draws upon contemporary social issues by making connections through personal narratives, history and popular culture. Her studio practice combines, research methodologies and artistic strategies borrowed from various disciplines such as photography, documentary, performance, storytelling, installation, graphic design and social interventions. Under the imprint of Eighteen Publications, together with her partner Mike Mandel, they have published her work and their collaborative works: The Turk & The Jew (1998), webAffairs (2005), The State of Ata (2010), They Came To Baghdad (2012), Lockdown Archive (2015), Campaign (2018), Strategic Planning (2018), Defunct Colleges (2019), Drop Dead Gorgeous (2020), Arsenal News (2021). She has had solo shows of her work nationally and internationally. Her work is in the collection of Yale University, the Addison Gallery of American Art, and her artist’s books are in numerous public artist’s books collections. Zakari is a Professor of the Practice at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University.

Instagram: @show.n.tll

Pictures From The Outside

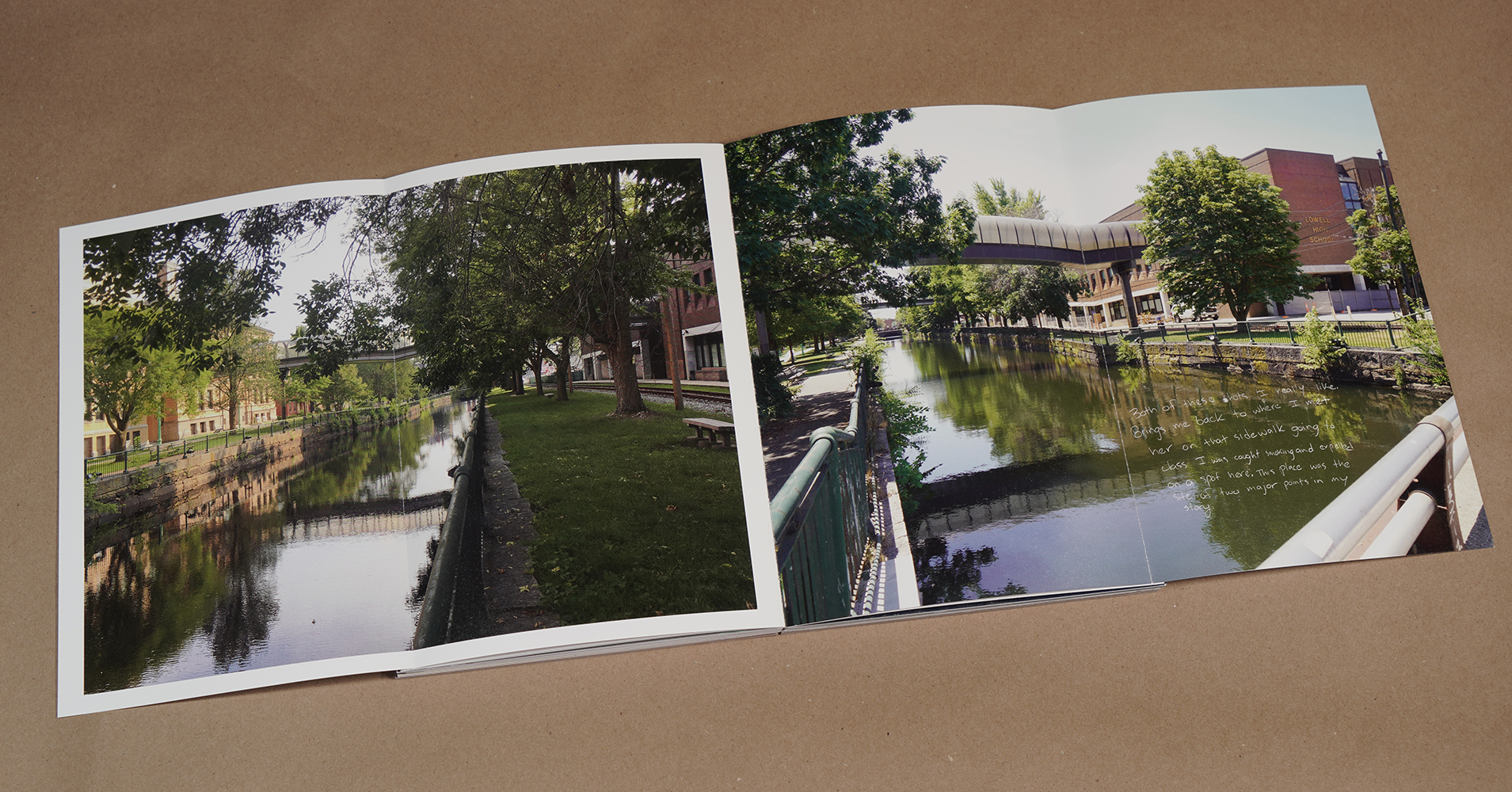

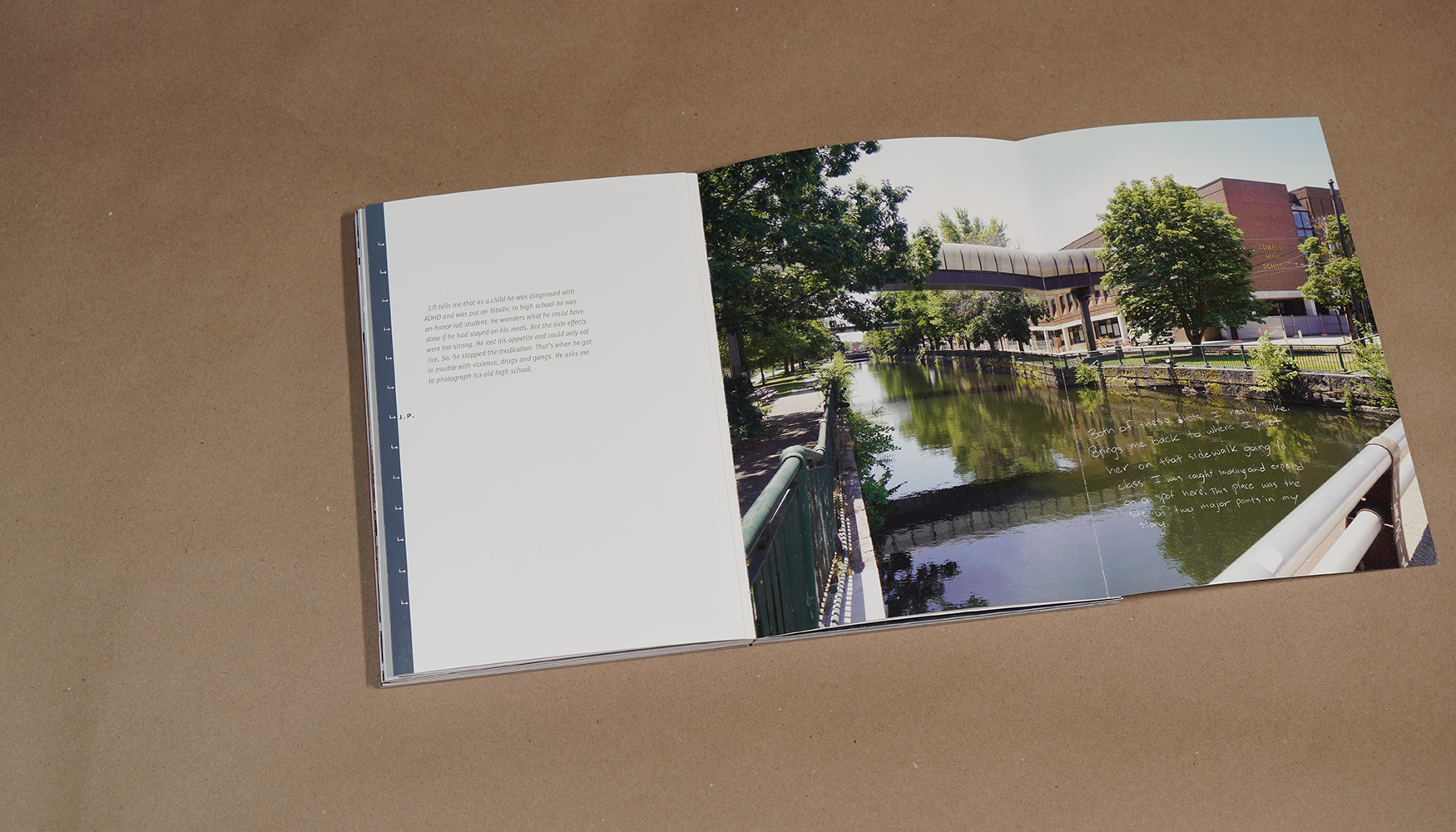

Chantal Zakari asked thirteen incarcerated men if they would like to have a photograph of a place from the outside. She asked for specific instructions on how to make the pictures. The men drew diagrams, maps and wrote descriptions based on their memories of the place. She then traveled to each location and made the photographs. The requests were of childhood homes, high schools, locations of happiness and sadness, courthouses and places where their lives were irreversibly altered. Upon her return with the photographs, participants responded with a piece of writing that vary from childhood memory to epic fantasy. At its core, this collection explores how an architectural space is remembered after years of incarceration. But the work evolved to an exploration of urban spaces, a reflection on changes due to gentrification, and in general, the psychological effect that architecture has on shaping our lives. The combination of images and the accompanying texts is a collection of stories about seeking redemption.

Sara Bennett: Can you tell me how this book came about?

Chantal Zakari: I teach an art and design course inside the prison to students pursuing a BA degree. The course teaches students design skills, basic knowledge about typography, and computer skills through the creation of their own artists’ books. This book started as a collaborative classroom project. I wanted them to explore the idea of conceptualizing an artist’s book.

We were able to get permission from the Department of Corrections to build a classroom library of artists’ books. Out of the forty or so books we had, some really spoke to the students. For example, Sophie Calle’s Exquisite Pain, where she is comparing her own pain to other people’s pain; Jim Goldberg’s Rich and Poor where the person photographed gets to respond to how they see themselves represented in his photos; Glenn Ligon’s Housing in New York, where he maps the changes in New York’s real estate through telling us stories about the various places he lived while growing up; and Bill Burke’s Mine Fields, which weaves his personal crisis at home—his divorce— with the greater story of devastation and war that he documents in Southeast Asia. These four books instigated good classroom conversations about how we think of image and text relationships to create meaning in books.

So we were planning a collaborative project when I asked them if they wanted a picture of a place from the outside. Their choice was not random. They were already deliberately thinking about the meaning of that place and they were well aware of the conceptual parameters of the project. Their choice was not only about longing for a place after years of being incarcerated, but also about choosing a symbolic place to express themselves. And of course it had to be a place that is a reasonable distance for me to drive.

I asked them to draw a diagram of exactly how they wanted the photo to be made. I wanted them to be my art directors. But this was also a test of their memory. Some had been inside for 20, 25 years. Memory is less dependable when emotions are involved. One creates new truths over time, and your memory shifts. In fact, in the book, you can see examples of that. In some maps the person can’t remember the name of the street, but curiously he remembers other details.

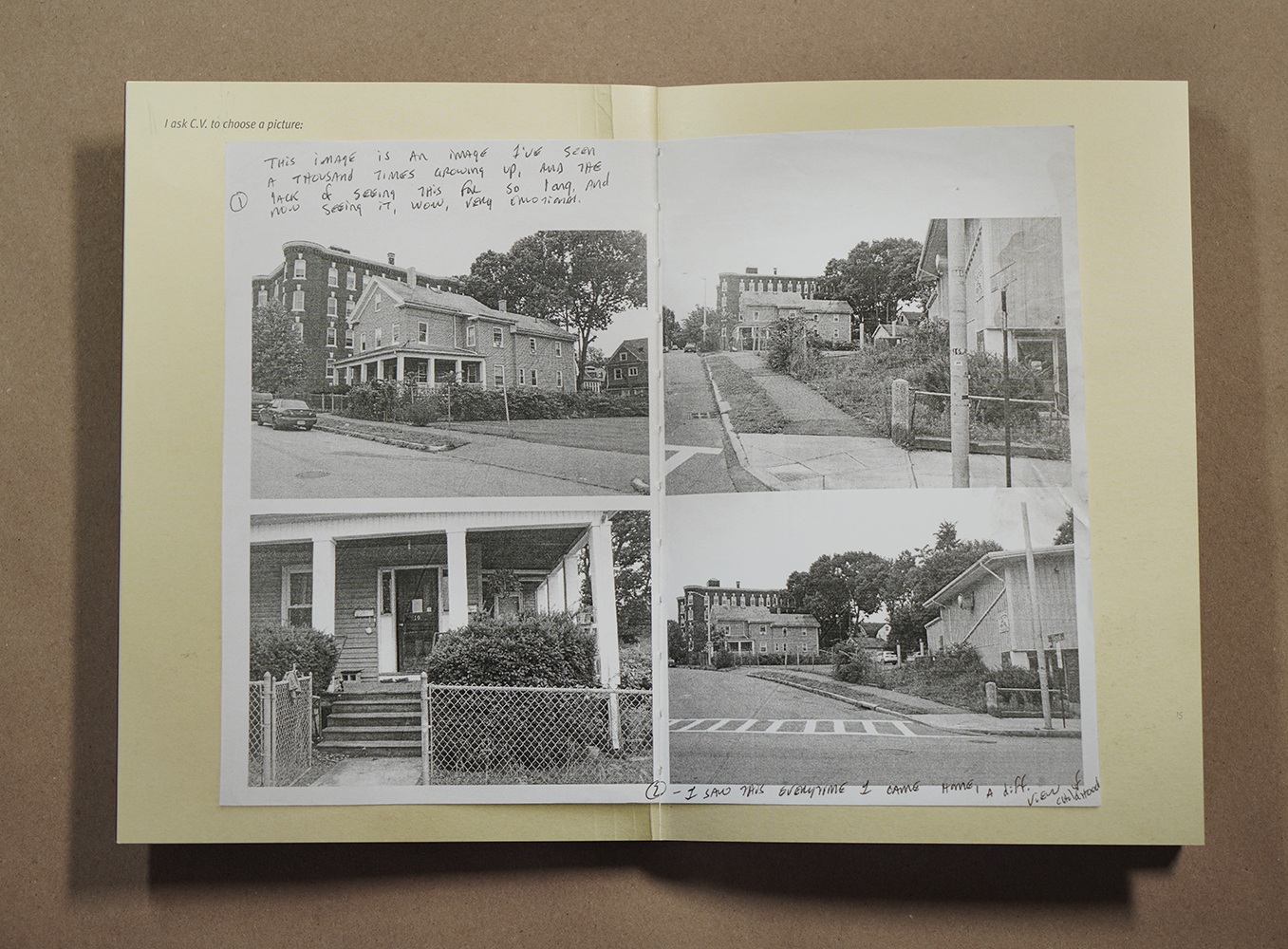

So I went out, and made the photos, and brought back several variations of the images they requested clumped together on a black and white letter sized print, a sort of proof sheet. I asked them to mark the photo they liked. This was a way to have them be photo editors. They had to think about the framing, angle, perspective, light in the photo and how these elements change the meaning of an image.

SB: It must have taken a lot of trust for them to do that. How did you build that kind of relationship?

CZ: Yes, that’s what you have to do when you teach an art class. You have to build relationships with each students and create a trusting community so that you can have class critiques. The group was already very close to each other because they had taken many classes together. My three TAs and I were the newcomers.

SB: Did you have this idea in mind when you started teaching the class or did it happen more organically?

CZ: It came organically. Knowing what interested them from the books in our classroom library informed me. I could see they were really interested in Sophie Calle and Jim Goldberg’s approach. So I knew I wanted to do something about responding to an image. They were making a lot of drawings on paper and on the computer. But I was trying to incorporate photography into the project because they couldn’t make their own. This project was also a way for them to start thinking about their own books.

SB: What did they make books about?

CZ: Lots of things. Some are very abstract. One is about windows, and what the artist imagines seeing through these windows. Others are more concrete in their approach. There is one that is a love letter to his family and includes photos of family snapshots. Some use the format of an artist’s book real creatively; a dos-a-dos book about the game monopoly, on one side he is a winner, but when you flip the book on the other side he is losing the game. A rap poet made a book using his text visually and created collages to go along. Another made a book of drawings of nude bodies juxtaposed with corporate logos and luxury products, a critique of capitalism. Another, chronicling his time in prison with passages from the Qur’an and some amazing Arabic calligraphy he built on the computer. At the time the class was at the credit equivalent of third-year college students, so they had already taken tons of liberal arts and science courses before my class.

SB: What happened to the books they made?

CZ: We were able to print them and each student and their families got copies.

SB: What were the men’s reactions when they saw the photos you had made?

CZ: Many were emotional, one got teary eyed. C.V. had been incarcerated for about 25 years. He had specifically asked me to photograph his childhood home from the perspective that he would see it when as a kid he came back from school. And so this photo is really the vision he had kept in his mind for all these years.

SB: You really captured the image he wanted.

CZ: C.V. told me exactly where to stand when photographing, which direction to shoot. And the image I brought back was precise.

A similar request, N.M. asked me to photograph a nightclub from a long perspective down the street. But when I designed the book, I realized that some of the photographs they chose were not necessarily the most expressive to an outside audience. So I added other photos that were more overtly emotional. For N.M., in addition to the photo he chose, I added another one that implies how festive this nightclub is. Throughout the book I included all the pictures they chose, but I also took the liberty of adding more in order to complete the story.

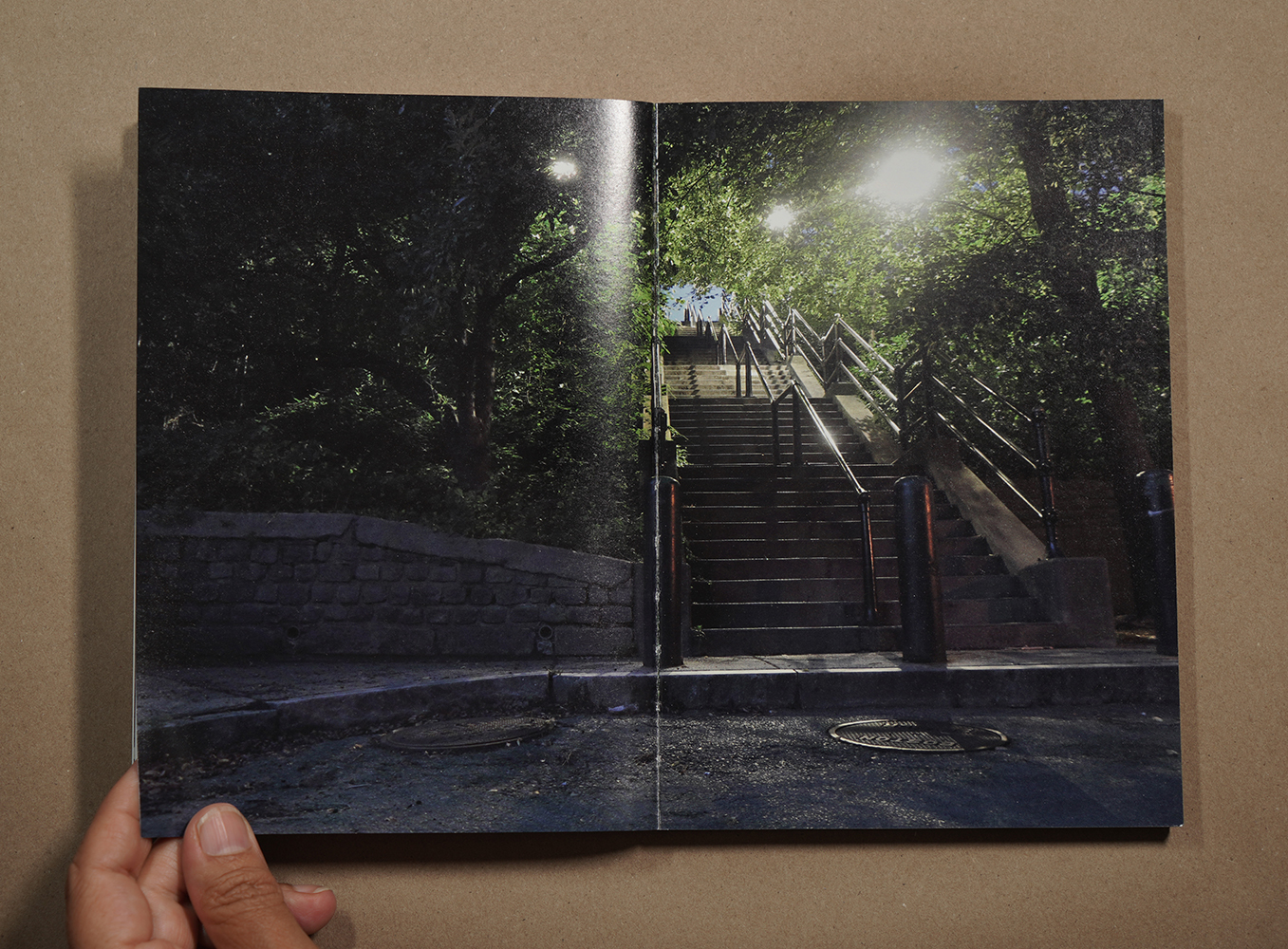

Another example, M.O. asked me to photograph a street alley with stairs leading to a street higher on the hill. He climbed these stairs every day on the way to school. In his directions he wrote, “I trust your judgment,” but he also wrote very specifically “stand right here and photograph in this direction” which I did. But the neighborhood has changed a lot. So I chose to put a little sliver of the neighborhood so you can see luxury cars parked on the street. It used to be a working class neighborhood and has now changed to be one of the most expensive in the city. He was inside when the neighborhood was transforming.

SB: C.M. asking for the back entrance of the courthouse really stood out to me as an interesting request.

CZ: Yes, that’s why it’s on the cover as well. To me it’s the heart of the book. In his request C.M. wrote “that’s where the inmates go in” and he recognizes that this is where as a person he was redefined by society. It’s the acknowledgement that going through that door really changed the way people see him.

Overall, there are repeating themes. There is home, the neighborhood, and then what the sociologist would call the third space—the dance club, the playground, the bodega or the masjid—places where you find other kinds of communities.

SB: I just love how the book looks and I’m so glad to have the physical copy. The binding and cover remind me of the rustic hand-sewn books I used to make when I was a teenager, with covers out of cardboard.

CZ: I wanted to make something that did not look luxurious, and an object that was a little bit humble, understated and quiet. And so I wanted it to look a little bit like a sketchbook, a little bit like a notebook, and a little bit like a diary.

SB: That’s exactly why I find the aesthetic so appealing. The work is also subtle and yet there’s an underlying emotional pull. I can feel the men’s longing for something they haven’t seen in decades. I came to photography from an advocacy perspective, but you’re a professor teaching the art of the book. And yet you managed to show something so profound about people we lock up for decades.

CZ: Well, thank you for saying that. It’s good to hear your observations. You’re really the first person that I’ve shared this book with since it came back from the printer.

I want to say that your approach of creating portraits of people in institutional spaces is incredibly important. It creates a vivid image of the life incarcerated people lead in the prison system. It’s just a different approach.

For me, this book is not about taking a political stance about incarceration or prison reform, although I have a lot of opinions about it. I didn’t see this book as a didactic and overtly political piece. The primary reason for the book was to satisfy a classroom assignment. So my driving force here was to have the students have the opportunity to experience the conceptualization of a collaborative and participatory artist’s book: how you think about an idea, how to choose a photograph, how to edit, and how to think about text and image and diagrams all working together to create meaning.

In the process I wanted them to talk about memory and the connection to spaces that they’re missing and not able to see. That’s when it became a book for an audience other than our classroom community. The project transformed into self-portraits through the spaces they chose. My design enables a more linear progression and creates connections. So, I see the book as a form of portraiture through architecture, and public spaces that are stored in their memories.

SB: I also find the accompanying writing so powerful. And I like how their choices are so different, from reflections to memoir to fiction and even fantasy. Did you edit?

CZ: Lightly—Spelling mistakes, commas, that kind of editing. This wasn’t an English class where I had to give them feedback on the structure of the text they wrote. I wanted this to be their honest selves. And an artifact of the project as well.

SB: That honesty is so palpable.

CZ: They are some of the most honest and open students I’ve had. M.O. wrote about stairs in the photo we discussed earlier, “I chose this picture because it brings back memories of my childhood and adolescent years. At the top of the stairs, there is a church, which to me represents goodness. Climbing the stairs, and the distractions that kept me from making it to the top, symbolizes my journey towards trying to become a better human.” That was really him thinking in a very symbolic way about what this photograph means. It’s about redemption.

SB: Do you feel changed at all by this experience of teaching in prison?

CZ: Absolutely. I mean, as humans, we change all the time. I make books and I make art so that I can change, so that I can learn. To me, art is a process and through that process, you discover and grow. It was incredibly satisfying to have students who were 100% there and who 100% wanted to learn. I felt very privileged to get to know them and be able to work with this group.

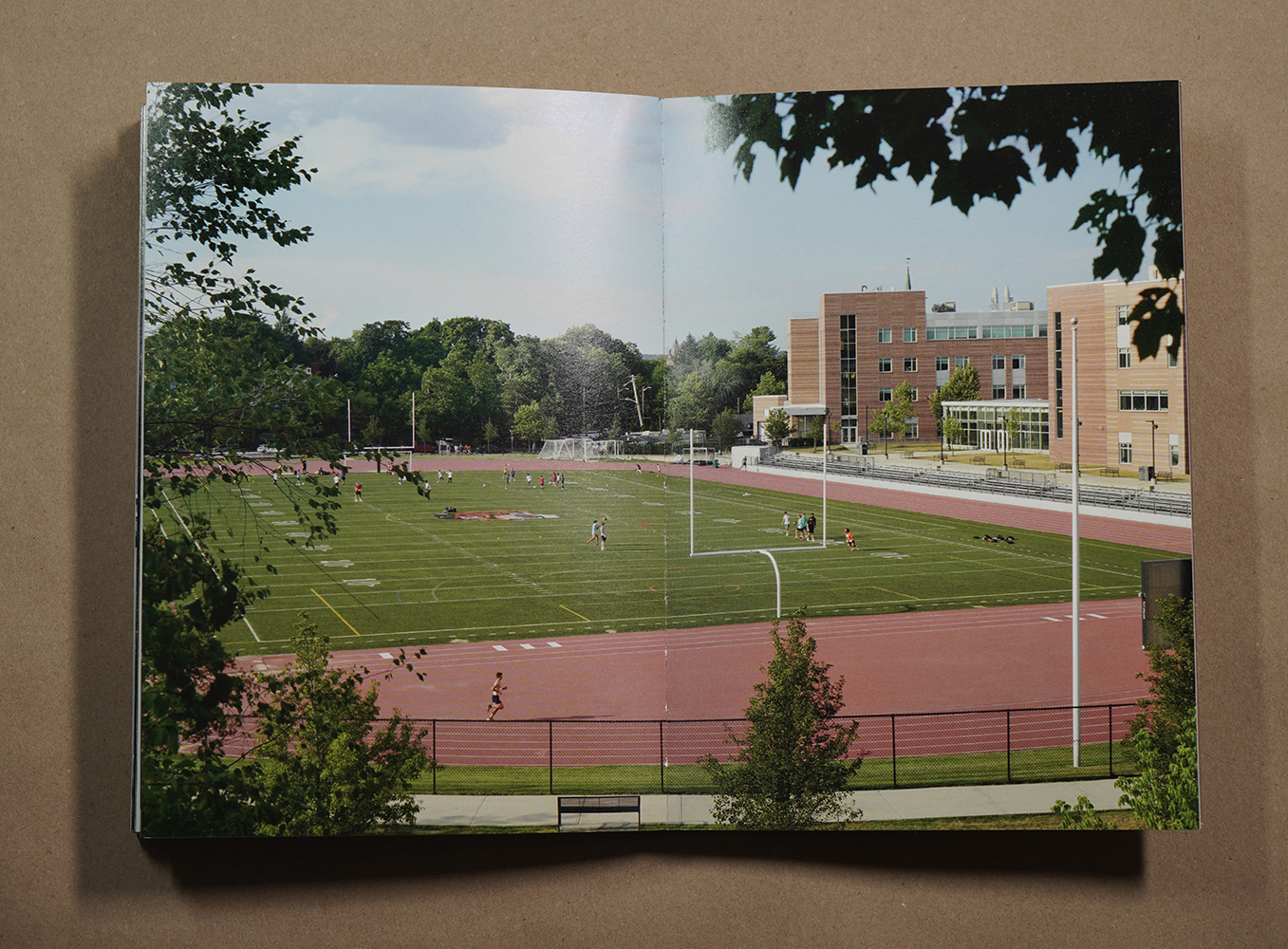

Through this project I ended up going to neighborhoods that I may never have visited and being in spaces where I might imagine their lives before they were incarcerated. For instance, S.J. wanted me to photograph his middle school in black and white and the football field in his high school in color. He went to an inner city prep school and then a very privileged high school in a wealthy neighborhood where he got to be on the football team. I was trying to imagine what it might have felt for him to be on the field after winning a game. This was a place where he had been successful and very much celebrated. And so I end the book with the hope that he would be able to get to that state again, with the hope that they, all the students in the class, can go back to their football stadium where they were stars.

SB: I think that’s the perfect ending for this interview, getting incarcerated people back to a life where they’re successful and celebrated. Thank you so very much.

Pictures from the Outside

Chantal Zakari with CV, KW, JS, AI, RG, SA, JP, TB, MO, NM, SM, CM, & SJ.

hardcover

with tip-in photograph

open spine binding

5.8 x 8.25”

136 pages

and two double fold-outs

Eighteen Publications, 2023

edition of 500

book launch September 8 – Kingston Gallery, Boston

release date September 15

ISBN: 978-0-918290-17-5

$45

Purchase at: http://thecorner.net

Printing was generously supported by a Tufts Faculty Research Award. All profits will support the Tufts University Prison Initiative.

After 18 years as a public defender, SARA BENNETT turned her attention to photographing women with life sentences, both inside and outside prison. Her work has been widely exhibited in solo shows, including at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR, Photoville in Brooklyn, NY, and Rotterdam Photo 2023, and in group shows, including the Blanton Museum of Art’s Day Jobs, MoMA PS1’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration and the Museum of the City of New York’s New York Now: Home. Her work has been featured in such publications as The New York Times, The New Yorker Photo Booth, and Variety & Rolling Stone’s American (In)Justice. Her entire portfolio can be seen at sarabennett.org.

Follow Sara Bennett on Instagram: @sarabennettbrooklyn

©Sara Bennett, STACY, 45, in the college office at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility (2019) Sentence: 30 years to life Incarcerated at the age of 30 in 2004 “There are days I wake up in a fog. I think I am home. After all this time—it feels good and it hurts all at the same time.”

©Sara Bennett, YVETTE, 54, outside the housing unit for the medically unemployed at Taconic Correctional Facility (2019) Sentence: 25 years to life Incarcerated at the age of 32 in 1997 “When you look at me you see the face of what society has deemed a criminal . But when you look at me and other women like me, see who we really are. We are mothers, wives, sisters, aunts. We are not just numbers. We are women who love the same thing in life as anyone else. See me as the woman I am today, not 22 years ago.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

Kristine Nyborg: Learning to Speak BearApril 1st, 2024