Tama Hochbaum: As If A Mirror

At first glance the work by Tama Hochbaum looks to be vivid, colorful abstractions of her portrait, however, upon deeper reflection, Hochbaum’s work represents memory and place at a specific time in her life. This work is not only a physical portrait but also a portrait of the activities, thoughts, and emotions Hochbaum was experiencing at the time. Using multiple layers of photos and varying effects, Hochbaum’s “As If A Mirror” roots itself in the ideas of memory and emotion as the work explores who Hochbaum is beyond her portrait.

“As If A Mirror ” is on display at Horace Williams House through December 31, 2023. Hochbaum has a video installation as part of this exhibition and can be viewed here.

Tama Hochbaum was born in New York to her mother, Adele, who was a child of immigrants. Tama’s grandparents came to the United States to escape the pogroms in Czernowitz (now Ukraine.) Tama’s father was an immigrant himself, coming to New York with his family, from Poland. Tama Hochbaum studied printmaking at Brandeis University, with Michael Mazur, whose voice was, and is, always with her in the studio, and in the world. Mazur encouraged her to study printmaking at Atelier 17 in Paris on a Thomas J. Watson Foundation Fellowship. After returning from Paris, she became a painter for 20 years, and received an MFA in Painting from Queens College, City University, before turning back to a camera. Over the years, Hochbaum has photographed with a Pentax film camera, Leica film camera, several pinhole cameras, a Hasselblad medium format camera, a Leica digital camera, and finally an iPhone. Hochbaum was represented by George Lawson Gallery, San Francisco and Los Angeles, for 10 years. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the William Benton Museum in Storrs, Connecticut. She now lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where she works and co-chairs the Art Program at Preservation Chapel Hill’s Horace Williams House.

Follow Tama Hochbaum on Instagram: @hightree19

As If A Mirror

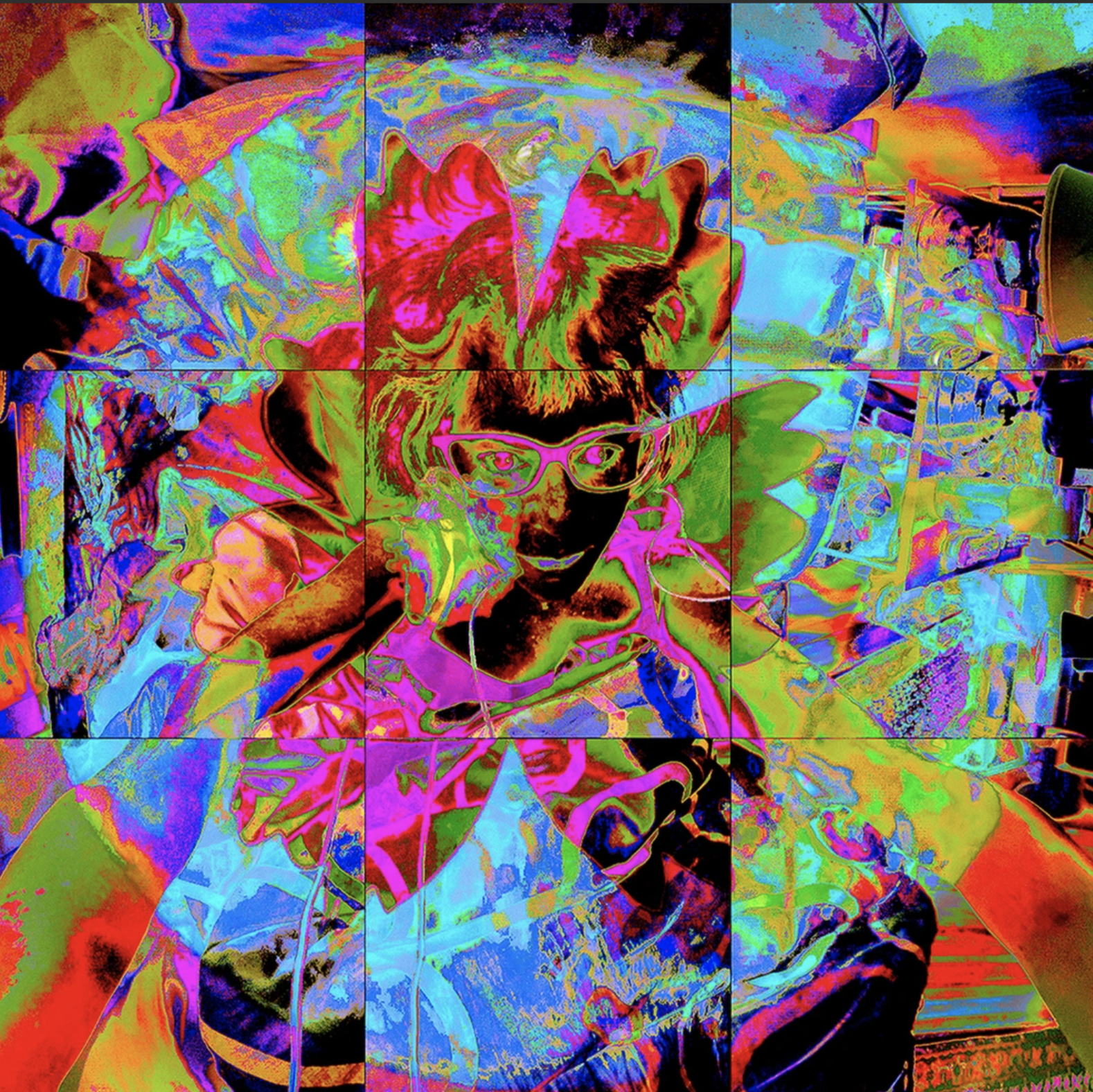

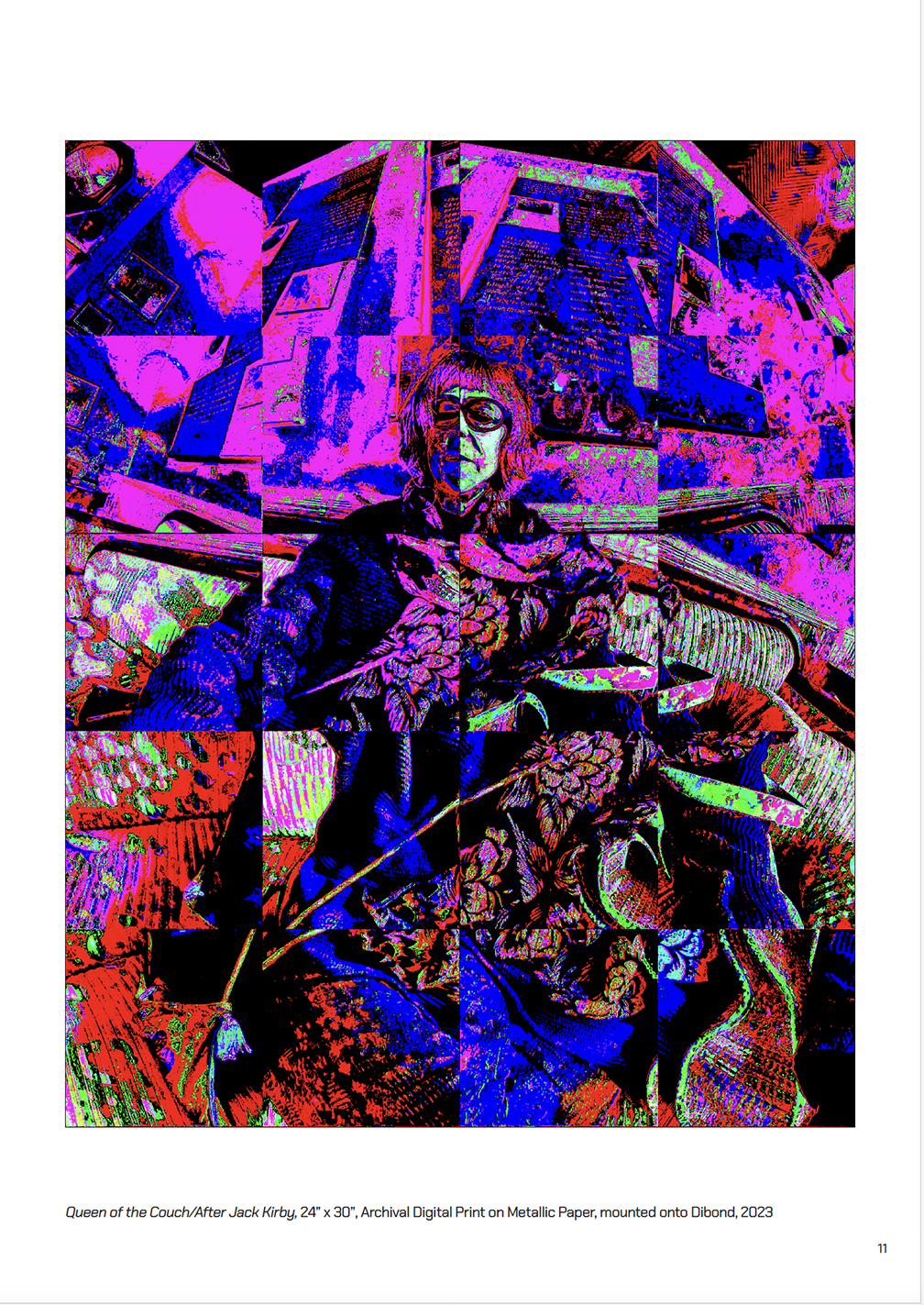

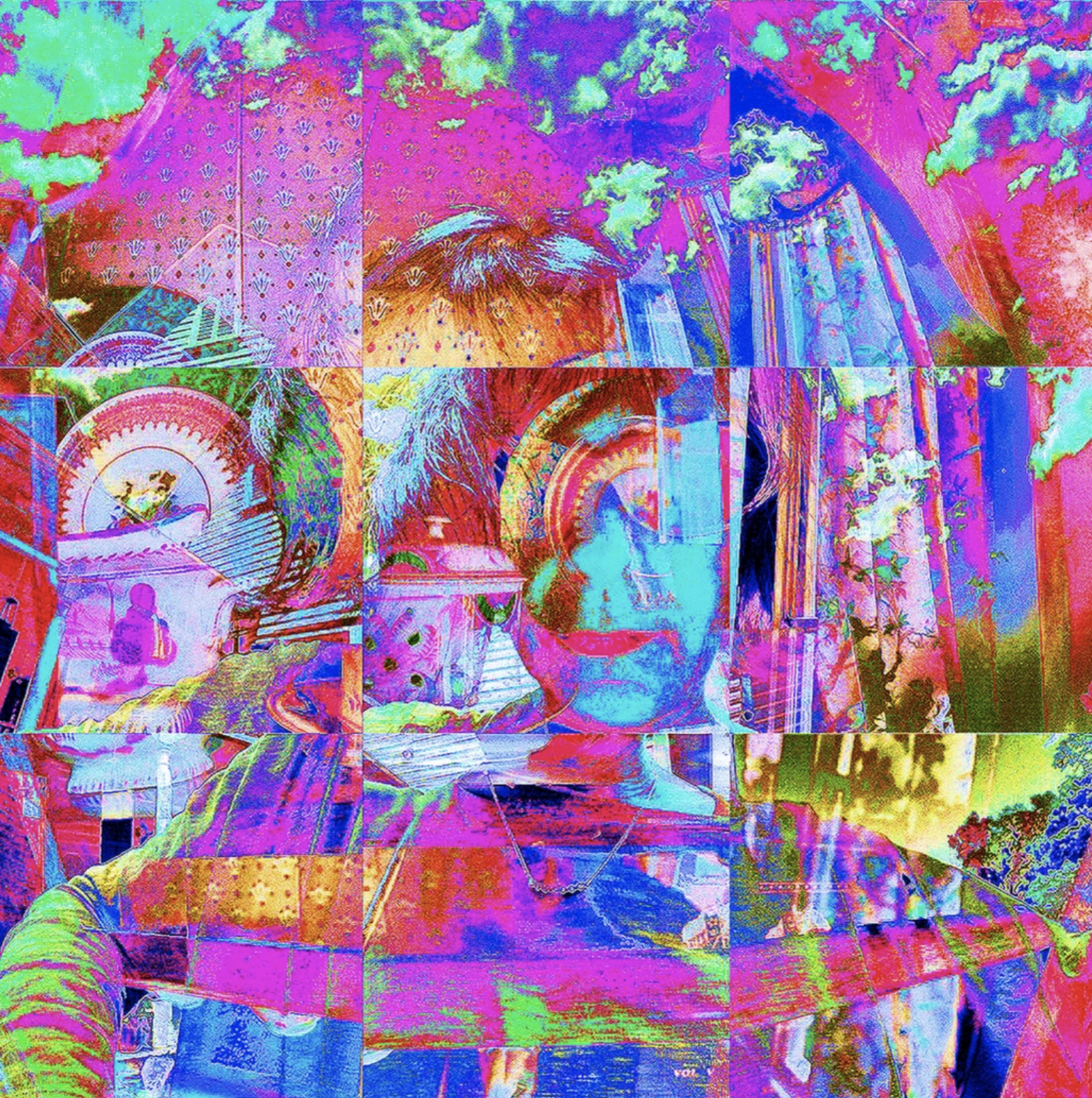

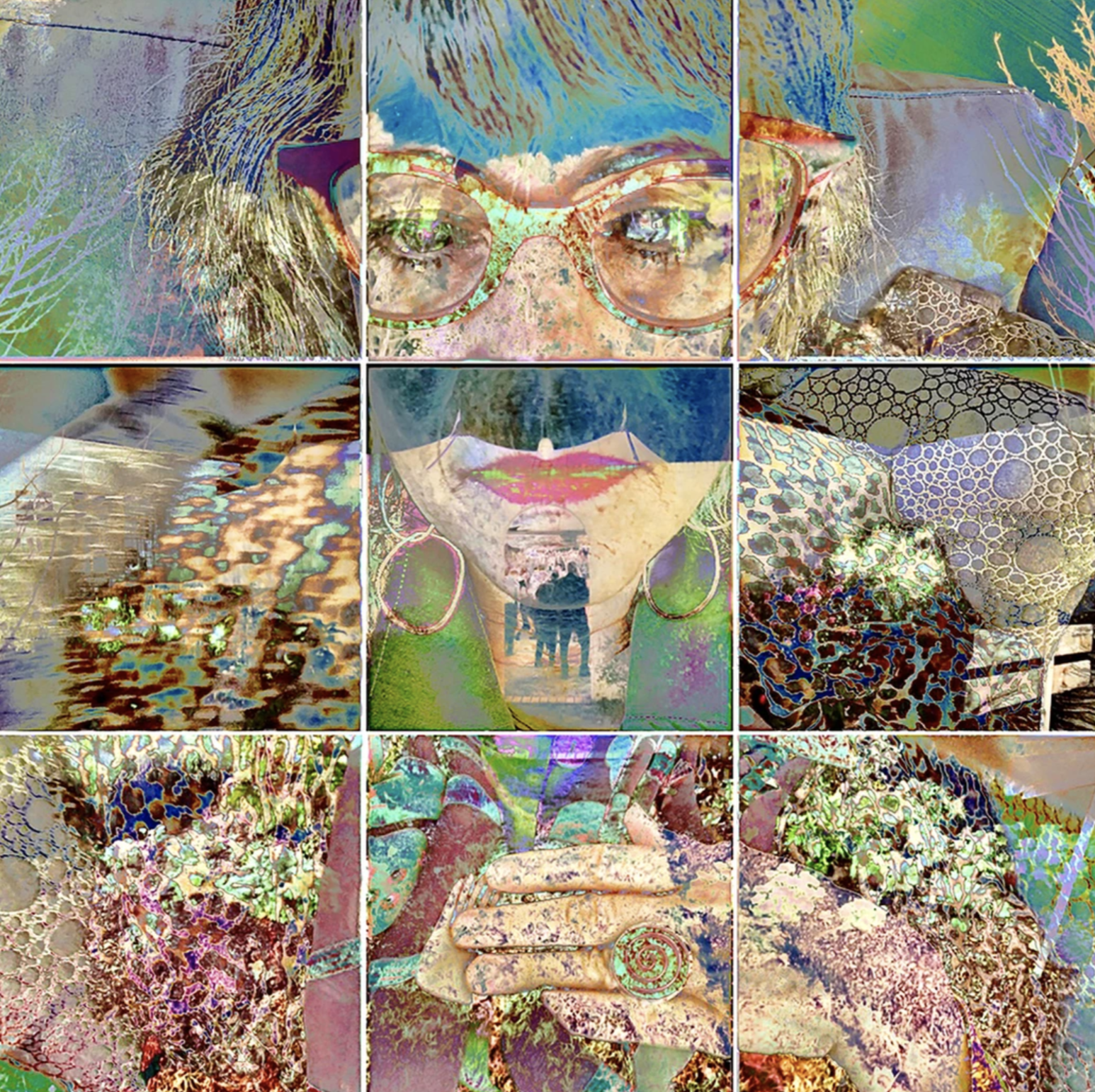

The self-portrait, by its very nature, is linked to an artist’s identity. She insists on her relevance, her existence, even, through her representation of self. Over the course of two and a half years, I created numerous self-portrait images, with each one subjected to multiple digital processes, producing enormous numbers of variations. A subtitle for the portfolio, As If A Mirror, could be “Theme and Variation, and Variation, and Variation, Ad Infinitum”. The process consisted of layering a gridded self-portrait with disparate images: scenes from my garden, beloved objects, a room in my house, a place I had visited, for instance, all of them screen-captured grids, chosen from my iPhone’s camera roll because of a particular format, say, or composition, or color scheme. The starting point is always a self-portrait. The second gridded layer changes with each new creation, depending on the time of year, what sparked my interest, where I was sitting at the moment, what I fancied as significant at the time, for example. The subsequent blended layers’ facets mix, push and pull in an always surprising way, like a visual square dance. The resulting image presents at times as a mosaic, at times as a tapestry, at times as a painting.

Jason Farago, in his New York Times essay on Albrecht Dürer’s 1500 self-portrait, implies that the artist presents “the self as a subjective individual, the author of one’s own life story”. My self-portraits, consciously self-centered, are vibrant, deliberate, fabricated, staged composites that state, I am here, and this is my story. -Tama Hachbaum

Kassandra Eller: Thank you for agreeing to discuss “As If A Mirror.” The minute I saw this work I was enthralled with the way you compose your images and the multitude of layers you indue in your work. I would love to begin by discussing your photographic journey. How did you find your love of photography?

Tama Hachbaum: Thank you, Kassandra, for the kind words about the work in “As If A Mirror.” My love of photography began in 1975 when I went to Paris to study a new kind of color printmaking that was being developed at the time at Atelier 17, a historic print shop where many artists in the early 20 th century had worked and which was still thriving at the time I arrived there. I traveled to, and lived in, Paris on a Thomas J. Watson Foundation Fellowship, having graduated from Brandeis University with a degree in Fine Arts and a concentration in printmaking. My sister had graduated from Cornell University a few years earlier with a degree in Graphic Design and as part of her course load she had taken a class in the black and white photography darkroom. In preparation for my trip, I decided to buy the same camera as my sister had used (I have spent my life emulating my big sister), and so I purchased a Pentax Spotmatic F and rolls and rolls of black and white film. I took enormous numbers of photographs while living in Paris and traveling in France. I returned to the States and decided, after years of being a printmaker, with all of the intricate and complicated parts of making a print, the multitude of steps it took, with acid resist grounds, acid baths (I was exclusively an etcher), chemicals to wash off the ground from the plate, applying the ink, wiping the ink off the surface, running the plate through a press with a dampened and blotted piece of paper, peeling off the paper to get the final image that was, in the end, the opposite of what one had drawn on the plate, that it wasn’t what I wanted to be doing anymore. I had loved the process, until I didn’t. I decided I wanted to paint, to apply a substance to a substrate and have that be the result. And I did, paint. For 20 years. During that period, I mostly didn’t touch my camera. I did think about photography, however; some years after my return from Paris, as an MFA student in Painting at Queens College, in NYC, I took a course titled “The History of Photography” with Robert Pincus-Witten, a brilliant Art critic. I loved learning about the medium that had had an interest for me some years earlier in Paris (and that I would become obsessed with 15 years down the road) and the photographers who mastered the medium. (An interesting sidebar – it was two women who inspired me the most during the semester course, Julia Margaret Cameron and Dorothea Lange. I wrote a paper on Dorothea Lange for Pincus-Witten; he tried to convince me to change my degree from the practice of painting to art criticism.) I really didn’t think much about photography again for another 15 years, till about 1994 when I began to take photos, again with my Pentax, getting the pictures developed commercially, bringing them back to the studio and making photo composites. When we moved to Chapel Hill, NC, for my husband to teach at UNC, I set up a studio for painting, but found myself drawn to taking photos of this very new, slightly wild, and, for me, very strange place that we had moved to, the South, and to learn how to print my own photographs. That was in 1996. 27 years ago. I’ve been obsessed with a camera, and photography, ever since.

KE: In your biography you state you were a painter for 20 years before finding photography. How has your experience as a painter informed your photographic work?

TH: Great question, Kassandra! I think about this a lot, and feel that the way I imagine a picture is circumscribed by the history of Art. My very compositional tendencies, the armature of my images, the space that interests me, come from having looked at, and made, paintings and drawn for 24 years previously. As Rachel Siporin says in the essay for the catalog for my exhibition, “Hochbaum is an artist whose photographs create a dialogue with art history, deeply informed by her artistic practice as a painter/printmaker. Rather than finding inspiration from the history of photography, these color photographs reference the process of drawing and painting: color relationships, mark making and brushstroke. Overall pattern’s active surface brings to mind high art and craft, but also nods to pop culture – comic books and 1960’s record albums.”

KE: Having an exhibition at Horace Williams House, where you co-chaired is quite the honor! What were your thoughts when learning your work had been accepted? How did you choose which works to include in the exhibition?

TH: The process of choosing artists to exhibit for the Horace Williams House is done by jurying. Artists apply to our program and the Art Committee of 7, including my co-chair and myself, decide on who will get an exhibit. We have become a very sought-after venue in which to exhibit, and it surely is an honor to be chosen to show with us. However, in the spirit of full disclosure I will say my exhibition was an invitational. I voiced my desire, as part of my 70 th year celebration, to have an exhibit at the House and my colleagues on the committee were happy to give me the fall slot to coincide with the CLICK Photography Festival in the Triangle. What to include in the exhibition was much more difficult. This series of self-portraits had me printing obsessively for 2 ½ years. I had previously shown work that was dye sublimation printed on aluminum at a production house. In other words, I sent away my jpeg and hoped for the best when it came back. With “As If A Mirror” I had complete control over the final state of the print as I was doing the printing. And print I did, repeatedly, all the many variations of all the many multiple-exposed images. I spent weeks designing the show – clearly, I know this space, I have worked here curating and administering shows for close to 20 years, and I wanted the show to look a particular way. The original set of images were in a square format and the more recent ones were very vertical. As you can see by my installation photos, the two long, back walls were hung in double rows of 5. I wanted the viewer to have the feel of walking into a comic book. I was also given the foyer of the House to exhibit in, which was a special allowance for my show by the Board of Directors of Preservation Chapel Hill. There are 36 photo composites in the show, but there are hundreds of others in portfolios that did not make it in. The choice was incredibly difficult.

KE: This body of work is quite personal and indicates this sort of reflection with yourself. What was the inspiration for this project and how did you decide the process?

TH: I am a restless artist. I have switched media, from drawing and printmaking to painting to photography, and the look of the work has changed drastically over the last almost 3 decades that I have been working with some type of camera. (There is an overriding theme to my entire oeuvre, but that’s an answer for another day.) My previous portfolio had been color gridded composites, of various spaces, at home and abroad, and before that I worked on a series of black and white images, large, gridded composites of the woods near my home, with the divisions between the modules almost fully eliminated so that the final picture came close to looking like a continuous image. In these, and in the previous portfolios of 360º pieces, symmetrical crosses and lintels, my feet are always in the image. It was a way to state – the artist is here! This is what I am seeing. I think I just really leaned into the idea of the artist being present, and presenting, simultaneously. In fact, I have always done self-portraits, as can be seen in this exhibit with the inclusion of my early paintings. Quoting Rachel Siporin again, “Originally, she was drawn to the self-portrait knowing that she was a dependable and readily available model, as she explored structure, light and shadow with respect to plane changes in her observational paintings.” But the images are me, and not me, at the same time. They are as much about process, and color, and time and memory as they are about my visage. The process of creating these images is quite complicated and was developed while I was making the pictures. There is a base layer of a gridded self-portrait which is then added to, blended with, as it were, another gridded image, of, say, scenes from my garden, beloved objects, a room in my house, a place I had visited, for instance, all of them screen-captured grids, chosen from my iPhone’s camera roll because of a particular format, or composition, or color scheme. The images are mixed in an app which produces various choices. The blended image gets blended again, curated, and mixed again and again until something comes up that satisfies my visual needs, that sparks my optical interest.

KE: When looking at your work one is engulfed by the colors and abstractions caused due to the layers. In your opinion what role did color play in this project? While creating the work, did you purposefully choose certain effects based on the content of the images?

TH: Yes, the portrait is often obscured by the colors, the contours, the images in the subsequent layers. Color played an essential role in this project. I mixed and blended the layers multiple times to achieve a palette that would essentially sing, would touch me in a familiar, yet surprising way. I wanted these images to refer to the 60’s (and a certain psychedelic palette) a significant time in the development of my taste. In other pieces, I reached for a palette that related to my paintings. There are several pieces titled after a particular artist whose paintings I loved and who came to mind once I printed the piece; one is “Hand on Heart/After Bonnard” which has a particular cerulean/cobalt/ultramarine blue with white that registers in my brain as Bonnard’s. I made about ten or twelve variations of this piece with other colors, titled as such, the “Hand on Heart/Celadon Green”, “Hand on Heart/Prussian Blue”. There are six of them hanging in the show. As far as choosing effects based on the content of the images, there was a certain choice involved in the process – I would choose, or curate, both the self-portrait I used for the first layer, and the second layer to be blended with that self-portrait because of a particular color format I noticed in the camera roll, or because of a certain composition that called to me. The image I used for the second layer depended on the time of year, where I was sitting while I was creating, what I fancied as significant at the time, for example. But the final image was always a surprise; I had control in the curation of the images I used for the layers, but not what would finally appear on my phone screen after the blending process. I could direct, but I couldn’t manifest. That was done for me, as if by magic. Of course, the installation design, the final curation of what is included in the exhibition is all choice, and all mine.

KE: This body of work includes portraits of you but is combined with images from moments of your life. I would love to discuss how you choose what moments to include in your portrait. Were there certain qualities you were looking for in an image?

TH: Another great question. The earlier, square-formatted images in a 3 by 3 grid, are quite different than the later, vertical pieces, and project a very different quality. Those earlier self-portraits were done in the midst of the pandemic and have an urgency about them. We were all worried, all the time, and that is obvious in those images. The portrait, and my glasses (the early portfolio was called “Through the Looking Glasses”) were right up flat against the picture plane. Again, to quote Siporin, “In her series, Through the Looking Glasses, boldly colored, square-formatted photographs, the self-portrait is front and center, her face pressed against the picture plane, with her lips and eyeglasses dominating the image. The frontal self-portrait dominates, although the space is abstract, non-perspectival, compressed on the two-dimensional picture plane. There is no entering the world that the artist exists in, as there was in the early self-portrait studies (paintings) of form and structure.” She continues: “The self- portrait is reduced to the lipsticked lips, and most importantly, eyeglasses pressed against the picture plane. The portrait has become a symbol for the self – the eyeglasses, seeing, the lips, speaking.” The more recent, vertical images step back, ease the tension of the somewhat confrontational squares, and include the space, sometimes mirrored, and hence, doubled, that I stand in. Their verticality implies the body having relaxed, and I even appear smiling in some, as the viewer sees me holding up my iPhone to the mirror to capture my reflection.

KE: It seems as though a project like this could go on forever, continually

photographing moments of your life. How did you know “As If A Mirror”

was a finished project?

TH: I agree, this project surely has legs. I perhaps should have added a secondary clause to the title; “As If A Mirror; Till Now”. The exhibition is, as I said earlier, part of my year-long celebration of my 70 th birthday. I may do the same thing at 75!

KE: To conclude I would like to ask what is next for you. Is there anything you are currently working on?

TH: Though I don’t know specifically what is next, I don’t have anything on the calendar, I am always working, always composing in my head and hands. I have, for many years, collaborated with my husband, the composer Allen Anderson, creating both Fine Art videos for presentation in a concert or gallery setting as well as creating installation videos for our artists for presentation on our Horace Williams House website. There is an embedded video on the current website for my show, called “Local Explanations: Mop Top/Bronzino”. The music was written by Allen, with my images in mind, and then sent to me to work with. I used about 40-50 images from a series entitled “Mop Top” as well as a secondary series using a detail from my favorite painting in the Ackland Museum at UNC, a Bronzino portrait. I sync my images to the music and create the final piece. It is a process I have truly loved, and we hope to do more of this. I have also been ruminating on the idea of possibly moving these images into a studio, taking them full circle, back to paint.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025