The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Daisy Patton

Studio Portrait with Untitled (A Walking Woman’s Collective), 90”x160”, 2020 Image: Daisy sits in front of a large painted photograph in her studio. Daisy is in a floral dress and has dark shoulder length hair. The large painting behind Daisy is a group of Bulgarian women sitting and standing together, with a photograph as its substrate. They are adorned with painted flowers, bright washes of color, blue grass, and a lavender sky.

This week we are exploring projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Daisy Patton is a multi-disciplinary artist born in Los Angeles, CA to a white mother from the American South and an Iranian father she never met. She spent her childhood moving between California and Oklahoma, deeply affected by these conflicting cultural landscapes and the ambiguous absences within her family. Influenced by collective and political histories, Patton explores storytelling and story-carrying, the meaning and social conventions of families, and what shapes living memory. Her work also examines in-between spaces and identities, including the fallibility of the body and the complexities of relationship and connection.

Currently residing in western Massachusetts, Patton has exhibited in solo and group shows nationally, including a solo at the CU Art Museum at the University of Colorado, the Chautauqua Institution and the Fulginitti Pavilion at the Center for Bioethics at the Anschutz Medical Campus, as well as group shows with MCA Denver, Spring/Break NYC, the Tampa Museum of Art, the Katonah Museum of Art, The Delaware Contemporary, the International Museum of Science and Art, among others. She has paintings held in public and private collections such as the Denver Art Museum, the Tampa Museum of Art, Seattle University, Fidelity Investments Art Collection, and in international airport Boston Logan with Delta Airlines, among others. Patton’s work has been featured in publications such as Hyperallergic, The Jealous Curator, Transition Magazine, The Denver Post, The Chautauquan Daily, The Seattle Met, and more. Minerva Projects Press has published Broken Time Machines: Daisy Patton, a book with essays and poetry on Patton’s practice that debuted spring 2021.

Patton has completed artist residencies at Anderson Ranch, the Studios at MASS MoCA, RedLine Denver, Minerva Projects, and Eastside International in Los Angeles. She has been awarded a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant, a Barbara Deming Memorial Fund grant, an Assets for Artists Massachusetts Matched Savings grant, a Montage Travel Award from SMFA for research in Dresden, Germany, as well as longlisted for the Aesthetica Prize 2022. She earned her MFA from The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Tufts University, a multi-disciplinary program, and has a BFA in Studio Arts from the University of Oklahoma with minors in History and Art History and an Honors degree. Foto Relevance represents her in Houston, TX, and K Contemporary represents Patton in Denver, CO.

Artist Statement

“What rituals are useful to locating someone who’s gone.

Our story has no language. My loss always in communication with your loss.”

—Ella Longpre, How to Keep You Alive

Who do we choose to remember, and how? This fraught terrain encompasses family relationships, identities, and collective memorialization. For some, living memory can lengthen the presence of loved ones in our lives; we only succumb to a blank past when our histories are no longer recalled and held by those that once cared for us. The family photograph is a vessel for retrieving memory, but as time accumulates, these emotionally laden images become unknowable, missing their necessary translators.

Our ancestors’ lives are encoded into ourselves through complex interconnections, whether through epigenetics or other practices preserved through time. The inherent loss embedded in these discarded photographs is intertwined with the fragility of the body itself. The depicted bodies can both reveal and conceal embodied language, personality and cultural markers, as well as emotional and physical well-being. These ties to corporeality and lineages hold us in ways that can manifest widely—as a tender embrace, or even a suffocation.

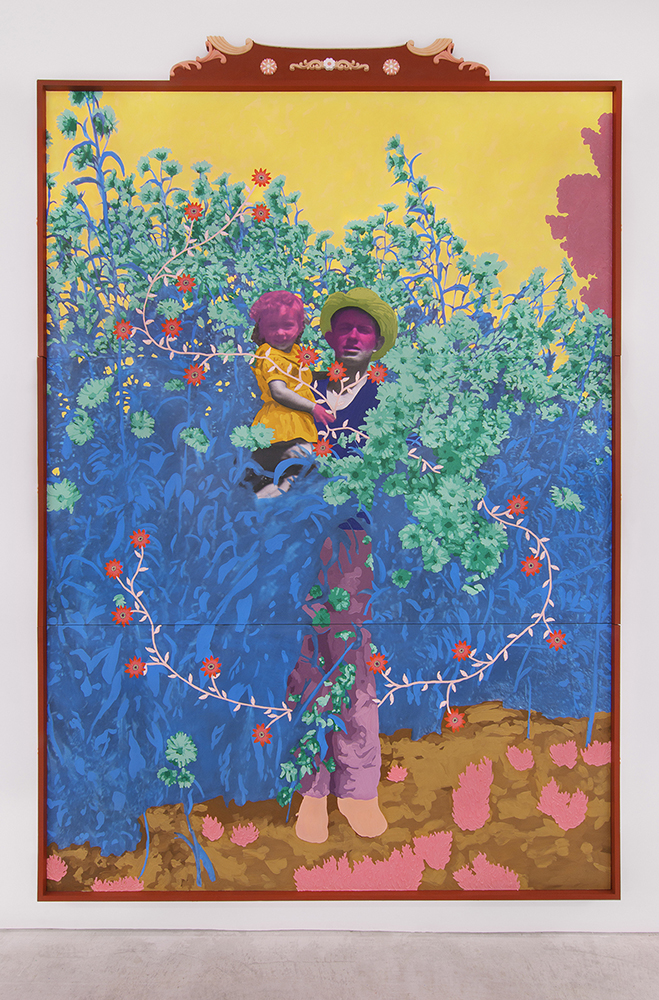

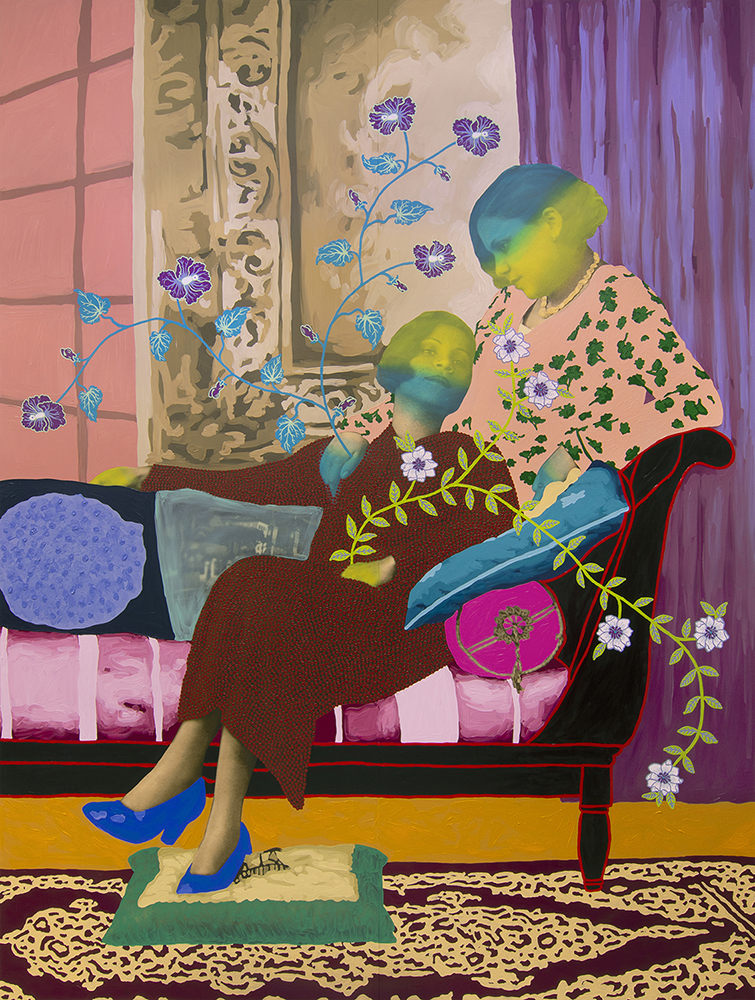

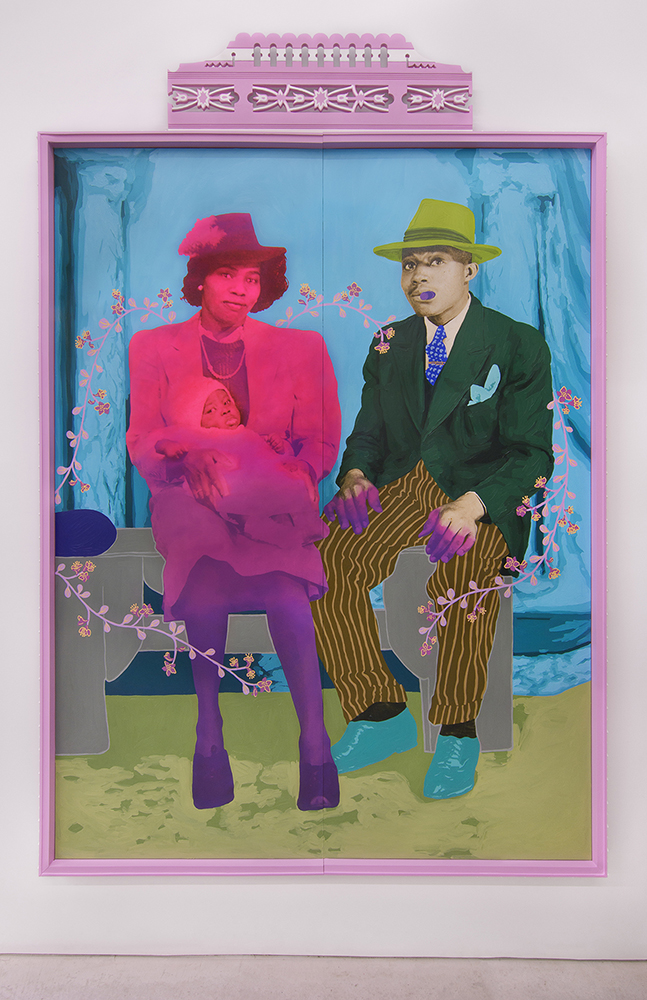

In Forgetting is so long, I collect abandoned family photographs, enlarge them to life-size, and paint over them as a kind of re-enlivening, dislocating the individuals from their formerly static place and time. Family photographs are revered to their loved ones, but if unmoored, the images and people within become hauntingly absent. Anthropologist Michael Taussig states that defacing sacred objects forces a “shock into being”—suddenly, we perceive them as present and piercing. By mixing painting with photography, I seek to lengthen Roland Barthes’ “moment of death” (the photograph) into a loving act of remembrance.

The use of bright swathes of color and ornate patterns signify a kind of vibrant afterlife, and the people’s vestiges become visitations. Each piece functions as an altar for the departed, a portal that fractures linear time, and a possibility for rich connection between the viewer and the painted subjects. Floral vegetation, forever blooming in fragmented time, underline relationships to the natural world and the hereafter. These rewilded botanic patterns adorn and embellish the photographic relics with devotional marks of care. Nearly forgotten people are transfigured and “reborn” into a fantastical, liminal space that holds both beauty and joy, temporarily suspended from oblivion.

Untitled (Father and Daughter with Tall Daisies), 116.5”x78”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with wood pediment, 2023, Photo sourced from Norco, CA Image: A painting over a photo of an American father holding his young daughter in his arms,they both have light skin. Their faces are washed over in bright pink paint. Surrounding them is lots of foliage painted in bright blues, greens and reds.

MB: To start would you please tell us a little bit about yourself?

DP: I am a multidisciplinary artist based in western Massachusetts and from Los Angeles; my work is very much focused on history and memory. From a young age, I’ve been obsessed with different aspects of absence and presence, such as ghost stories and historical narratives. I chalk that up to growing up with a single mother, a white woman from the American South, and a father who I never met and was discouraged from learning about, who is Iranian. I was bereft when my family, which includes my younger sister, left Los Angeles for Oklahoma, where I spent half of my childhood. I’ve always felt haunted in some ways—by the past, by places I can never access because it has been dislocated by time, and of course by a body that continues to deteriorate.

MB: What does disability mean to you personally? Does it show up in your artwork or art practice?

DP: I’ve always been neurodivergent—my teachers in first and second grade tried to diagnose my ADHD in the 80s, an indicator of how delightfully chaotic I was—but I really didn’t see that as a disability so much as a different way of being and thinking. In January 2010, midway through my graduate program at SMFA, I was hospitalized and diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. The future I had laid out for myself immediately crumbled, and I had to slowly build back what my life would look like. This transformed my art practice from one that was more confrontational and voyeuristic to one that is more collaborative and empathetic in nature. My interests in history shift from political to social; I think questions around collective memory and who gets to be held in it are incredibly important, especially as we see so much dehumanization and deliberate erasure. I understood erasure from my own experience hiding my father and my Iranian heritage, being told to be quiet, and then the post-9/11 aftermath.

All this has filtered into my series Forgetting is so long, as well as reproductive justice series Put Me Back Like They Found Me on forced sterilization in the United States and Would you be lonely without me?, also centered on US history, specifically around abortion. Dealing with chronic illness that is so deeply uncertain and leaves so much damage in its wake, I can’t help but have those perspectives seep into the work I make. My painting is very physical, and I have spent the last several years trying to make the exact work I’ve always wanted to make because I just don’t know how much time I have left to do so. I nearly died in late 2021 after another autoimmune illness reared its head, Crohn’s disease (which is in my family), and the inflammation, combined with some other factors, caused a pulmonary embolism that I barely survived (thank goodness for the speed of an ambulance and the ER doctors!). I have mostly recovered, but my energy levels are lower and my work has become far more complex than before, so I have had to accept that my output is going to decrease over time sooner than I’d hoped. It has also sharpened the ethics of care that guide my practice and how I see my work overall.

Untitled (Dear half 5-4-1927)* *translated, Size: 80”x60”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel, 2021 Photo sourced from Cairo, Egypt. Image: Two women from Egypt sit together on a sofa. One woman is looking at the camera and leaning into the other women, who is looking down at her. Their faces are washed with yellow and blue paint and the photograph details are painted over in bright colors and adorned with flowers.

MB: You work with historical photographs, often family photographs or snapshots. Can you share more about that? How do you choose which photographs to work with?

DP: Photographs, for me, are precious relics; as objects, they have been touched and held, barely separated from us now to the person in the past who once possessed these images. I think about time from a non-linear perspective, and that informs how I work with found imagery. In the Forgetting series, it is about fracturing and fragmenting time to bring the person in the photograph to our present, to visit us once more despite the passage of time that would prevent that return. As someone who has only ever wanted a photograph of my father, I treat these photographs very carefully. I don’t alter the originals, but rather scan and enlarge the images to life-size to paint over. My selection process is very much based in Roland Barthes’ idea of punctum, something that pierces him. In my case, it’s a bit of falling in love with the person. That love is sustained as I choose what to paint next, and hopefully the person in the image becomes transfigured into a not quite alive visitor whose presence, I hope, reminds us of our collective responsibilities towards each other—of care and carrying their memories forward in time. I collect widely from across the world because I want to be specific about thinking of an archive of memory, but I make sure to preserve aspects of identity and place where I can. I think there’s something interesting about the everyday and how it repeats or rhymes despite space and time. This includes listing the location the photograph was sourced; initially, I did not have that information public because I worried some audience members might have racial/ethnic stereotypes that would change how they viewed the person in front of them. But a few years in, I realized people were doing that anyways, flattening and making assumptions that mirrored the erasure I felt hiding my father’s identity.

Untitled (Five Patterned Women on the Ledge with White Flowers), 96”x80”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel, 202, Photo from Iran sourced from NYC, NY Image: A group of 5 Iranian women are seated together on a ledge. They are in a row leading back into the image and all the women are leaning on each other and have an arm resting on the shoulder of the person in front of them. Their faces and hands are washed in pink or coral paint. The background is painted light pink and the edge of the ledge and drop off are a deep magenta.

Untitled (Seated Woman with Purple Clouds and Blue Vine with White Flowers), 40”x60”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel, 2021, Photo from Nigeria sourced from the United Kingdom Image: A Nigerian woman sits in a chair in a side profile. Looking off camera her mouth is in a slight smile. She has dark brown skin and is wearing a light purple dress and has on purple gloves. Over her forehead, ear and part of her hair are washes of purple in cloud form. The background is red and adorned with blue vines and white flowers.

MB: To me, a part of your act of transforming, painting, and adorning the photographs speaks to time. Connecting the past and present, deconstructing linear time. This idea of bending time (rather than bending or overexerting our body/minds) is also something that is talked about in disability circles. Can you share if this connection resonates with you and if so how?

DP: Yes to all of that! If we think of photography in the context of static time, death of a moment, then painting’s way of using time is more dynamic, not forced to see time in a linear fashion. It’s why it’s important to me to include both media in the Forgetting series; the histories of each medium are so intertwined and it made sense to continue that relationship here. The act of painting itself, the time and devotion embedded in those acts of mark-making, is so much about time falling away. I hit a painting block late undergrad that lasted until after graduate school, and it was because I couldn’t get into the flow state that makes painting so crucial for me. When I am painting, everything else is gone—my focus is so aligned with what I am doing that I will sometimes forget how my body is feeling, or the worries of what is happening around us, and so on. I credit painting again with slowing down my deterioration, and that lengthened time has allowed me to make work that has grown very complicated and time-intensive in ways I probably couldn’t have before my illnesses. It’s a strange space to be in: the pressure of working and making before more ability slips away, but also the expansiveness and what I can tap into have shifted dramatically.

Untitled (Pink Woman with Floral Stand), 100”x68”, Oil on archival print mounted to canvas with fabric, tassels, and embroidery, 2023, Photo sourced from Cairo, Egypt Image: A young Egyptian woman poses for a photo. She rests her hands on a tall decorative pedestal and she is wearing a deep magenta dress. Her face and half of her arm are washed in light magenta and coral paint. Surrounding her are white flowers. Around the frame are gathered pieces of floral cloth.

MB: There is such deep care in how you paint and adorn these lost or forgotten photographs. And the canvases you are working on a usually large in scale. What is this process like for you, physically and emotionally?

DP: The preparation process to making a painting is a lot longer than just putting paint onto a canvas; I have to select which image makes sense, figure out its scale to be at 1:1, print, either mount myself or have a fabricator do so, build cradles/hanging devices, more prep, and then finally painting. For me, painting is joy and torture, a wrestling match and constant learning process where I hope what comes out will be successful enough. I become very close with who I paint, but the process of painting can color how I feel about them, about the piece in general—I still have deep affection and if something doesn’t work, that failure is mine, not theirs. I climb on ladders, benches, tediously paint pattern, it’s all very labor intensive! I started doing Pilates with an instructor in 2020 and that has really helped manage the pain that comes from painting. After I finish a work, including now framing, I really need some space and time away from the work, which has been complicated by the pandemic. Seeing all the work together in an exhibition after months of work used to be so crucial to moving forward and understanding what came before.

Untitled (Tony’s Photo. Studio 1806 Point Breeze Ave. Phila. PA.), 92.25”x64”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with pediment, 2023, Photo sourced from Hinesville, GA. Image: A portrait of a Black family in the U.S., Mom, Dad, and baby. The father is wearing a green suit jacket and pin-striped pants. His wife is in a skirt and blazer and holding their baby. The woman and the baby are covered in a wash of magenta paint and so are the father’s hands. The background is a light blue and they are adorned with vines of light pink and yellow flowers.

Untitled (Three Generations with Ornate Rugs), 118.5”x81.5”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with pediment, 2023, Photo from Iraq sourced in Herzelija, Israel. Image: An Iraqi family of 6 poses for a photo. Three men are standing in the back, three women are seated in front, and a baby is held on the lap of the woman in the front row. There is an intricate rug on the floor and background painted over with purple, gold, pink, and yellow hues. Everyone’s face has a light pink wash of paint over it.

MB: I was curious to learn more about how you decide which parts of people to adorn or paint with these bright washes of color, almost like auras. Is it an intuitive process? What does it symbolize for you?

DP: I think about painting over photographs as acts of loving remembrance, and the color washes over faces, hands, and sometimes full body is almost like an aspect of touch, caressed in the same ways that a photograph is held. I imagine that the color washes are a kind of light, that the person could walk out of the picture plane and glow with the colors. So while I don’t ascribe to auras or that kind of specificity, I do think about the washes also as another nod to the disruption of time and their presence in a liminal space of not quite alive and not quite dead. I’ve used this technique since the beginning of the series in 2014. In 2020, I read and resonated with Kevin Brockmeier’s The Illumination, which is a novel about what happens to society if physical pain became visible through light—like a wound would emit a beam of light. Again, it’s not a hard connection, but these are some of the things I think about—loss as pain, these people existing in a fantastical space and the unreality of color denotes that, washes as glowing warm light.

Untitled (The Matriarch’s Funeral), 97.5”x141.25”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel, 2023, Photo sourced from Moscow, Russia Image: A Russian family is gathered around the body of a family member who has passed. All the women are wearing headscarves painted in bright colors. There is a man in a green coat in the middle of the group. The matriarch’s face and hands are painted in a magenta wash of color. Coming out of her funerary bed are blue vines with green flowers that weave through the family members.

Untitled (Pink and Magenta Woman with White and Gold Flowers), 35.25”x31.5”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with found mirror frame, 2023, Photo from Iran sourced in NYC, NY Image: A portrait of an Iranian woman. She faces the camera with her head resting on her hands which are draped on the back of a couch. Her arms are washed in magenta paint and her face in light pink. Adorning her are white and gold flowers in an arch. Surrounding the painting in an ornate wooden purple frame with open doors displaying the painting. The doors have tan bars and frame has tan painted floral designs.

MB: Recently you have started incorporating more decorative frames or furniture pieces turned into frames. What led to this evolution in your work?

DP: For years, I have seen this series as a form of sacred space, as altars to those who are forgotten or no longer with us. They’re also portals of connection and relationship, opportunities to be visited and to allow time to fall away. I’d wanted to explicitly make visual these aspects of the sacred for many years, most especially after my exhibit This Is Not Goodbye at the CU Art Museum in 2018, which was concentrated on funerary imagery. I moved a few times and had inadequate studio space or access to tools that would allow me to build until I was able to create my own studio last November. To me, it makes a lot of sense to continue complicating and adding more elements to these altars and ties into the spiritual element of visitation.

Untitled (With all my love, Silwa S.S. Studio Philippe), 46.5”x28”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with found mirror frame, 2023, Photo sourced from Cairo, Egypt Image: A portrait of an Egyptian woman. She is wearing a yellow dress with red flowers. Her face is covered in a magenta wash of paint. The background is light pink and there are light blue vines with blue flowers adorning her. The frame is a bright green with a scalloped top with a gold seashell in the middle. Painted on the frame are orange vines and turquoise flowers.

MB: How has the experience of the past few years, specifically the pandemic, influenced your work or your art practice? Especially work that is so inherently about connection, care, and loss.

DP: The on-going pandemic has devastated so much, and that includes my life and world. Because of the lack of safety, I cannot travel very far and can’t see my work on display. As you noted, I make work about connection—I want audience members to be moved emotionally by who they see. I’ve found that because of the life-size scale, viewers are able to have moments of connection that remind them of other beloved ones in their lives, and it’s why I think it’s really important to see the work in person, rather than just a screen.

In all honesty, I have struggled with this work as the pandemic continues its path of unmitigated destruction. People who I once trusted and felt safe with I don’t anymore; I feel more abandoned and closed off than I ever have before, including lost career opportunities, and that only heightened with my near death. I got to see what it would be like to die, and people’s extreme discomfort with the body and death means shunning anyone who reminds them of this. I am doing very well now and stable, though my doctors have confirmed that getting COVID would be catastrophic—which has obviously become more difficult as masks have been removed from medical settings.

I love connecting, I loved being around others and feeling that shared joy of togetherness; that has been replaced with dread and fear. Even going to see art in person has become more grief than the transporting happiness I once felt. It is hard to make work that is about connection, that I make so large to be impossible to ignore, while hearing things like “the vulnerable will fall by the wayside” as if that is a good thing. I began the Forgetting series as a way to preserve and carry forward those forgotten or lost in time; the work is about love and care in a world that punishes those for more exploitation and cruelty. I have tried not to become bitter because I still do deeply love humanity and all its foibles.

The work has always been political, and perhaps now even more because asserting that we all deserve care, joy, and safety is pushing back against our own collective dehumanization. The same people that want us to accept mass death and disability are the same people who want us to accept the destruction of the climate and force countless to become refugees, and the same people who want to see refugees and conflicts soar to accelerate mass death to cow the population and continue extracting. We don’t have to happily join in on our deaths, and I wish people would bring their radical politics around equity and justice to remembering that they are still in a pandemic that will harm them and those they love. I’ve had to censor myself often because most people do not want to really know about what is happening around them.

Even still, I dream of better futures and better tomorrows. I believe in what feels unattainable because historically, what seemed impossible once eventually fell. I want to live long enough to see that happen, but if not, at least I am planting seeds for the future I hope for.

MB: Who are some artists that have influenced your work?

DP: There are so many past and current loves! Thinking about mourning, loss, the body: Christian Boltanski, Doris Salcedo, Felix Gonzálex-Torres, Ana Mendieta, Oscar Muñoz. Painting/Drawing: Marlene Dumas, Gerard Richter (pre-abstraction), Njideka Akunyili Crosby, John Singer Sargent, Kerry James Marshall, Firelei Báez, Thomas Gainsborough, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Mark Rothko, Simonette Quamina, Hans Holbein, Cinga Samson. Experiences/Installation: Ebony G. Patterson, Janet Cardiff, Laurie Anderson, Nick Cave, Lee Bul, Effulgence of the North at the Velaslavasay Panorama in Los Angeles from 2016. And then there are my friends and peers whose work always inspires me (I can’t say how many times I just deep sigh in awe of their work) and pushes me to be better: Arghavan Khosravi, Allison Rodriguez, Anna Valdez, Ken Gun Min, Gio Swaby, Raheleh Filsoofi, Shabnam Jannesari, Ashley Eliza Williams, Hedieh Javanshir Ilchi, Sharon Louden, Kandy Lopez, Alicia Brown, Saj Issa, Camille Eskell, Dell M. Hamilton, Florine Desmosthes Elizabeth Alexander, Clarity Haynes, Genevieve Cohn, Rosie Ranuro, Salma Caller, Sammy Lee, Kate Bae, Maliheh Zafarnezhad, Erika B. Hess, A’Driane Nieves, Alia Ali, Scherezade Garcia, Leila Fanner, Meggan Joy, this list is long and could go on much longer—we are so lucky to be living in a time with so many incredible artists!

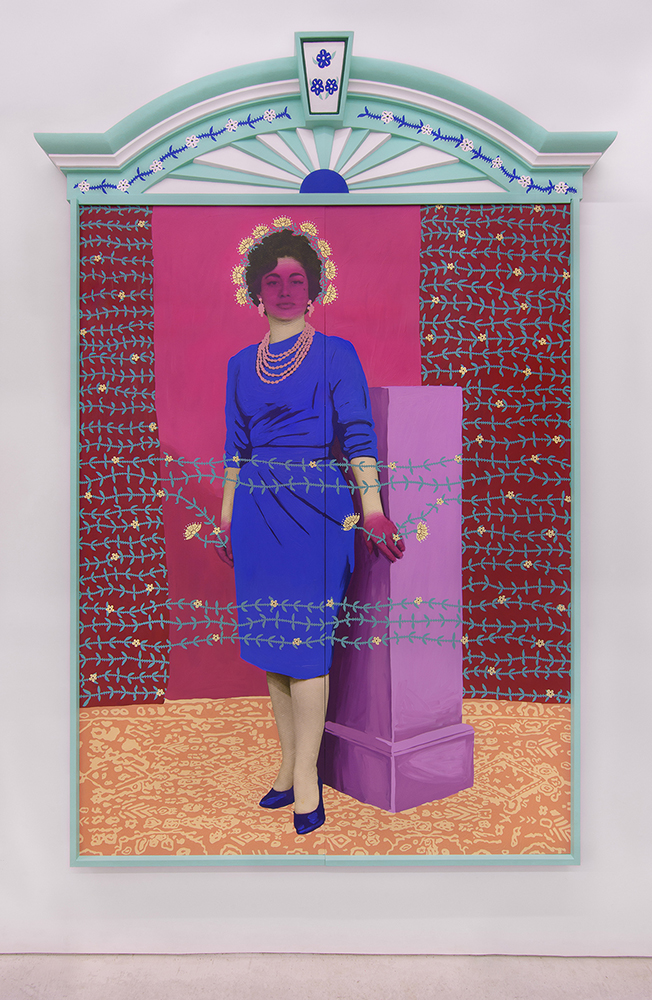

Untitled (Woman with Yellow Flower Crown and Patterned Curtains), 97.5”x68”, Oil on archival print mounted to panel with arch, 2020/3 Photo from Lebanon sourced in Los Angeles, CA. Image: A Lebanese woman poses for a photograph.She stands next to a purple pedestal in a deep blue dress. She has light skin and her hands and face are washed in deep magenta paint. She has a crown of yellow flowers across her hair. There is an ornate rug in orange under her feet. And behind her and sometimes crossing her body are vertical rows of vines with yellow flowers. The decorative frame is a light green with a sunburst design on the top. The sun rays vary between white and light green, painted with dark blue vines and white flowers.

MB: What are you working on now, or is there anything new or upcoming that you would like to share?

DP: I have a few shows coming up next year, including a May/June solo at Candela Gallery in Richmond, VA focused on women and female relationships, as well as and a two-person exhibit with the amazing Alicia Brown at UMass Amherst’s Augusta Savage Gallery in fall 2024, where my work will have an emphasis on women from the SWANA region. As part of those shows, I’ll be working on some new iterations on the Forgetting series, including canvas and fiber art that I’m tremendously excited about! In the same ways I’ve been thinking about altars and sacred spaces, influenced heavily by Persian mosques and Baroque Catholic churches, I’ve been thinking a lot about the visual languages of tapestries and Persian rugs, both in terms of narrative and the sacred. I also have a solo exhibit at Cuesta College in Jan. 2025 that will explore weddings and have some more sculptural, experimental work I am eager to dig into. I feel like I’m hitting my stride and making the work I’ve long wanted to make, and I’m thrilled to see what comes from it!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025