Exhibition Review: Aging Bodies at East Window Gallery

Installation view of Aging Bodies, Myths and Heroines, Courtesy of East Window Gallery

Aging Bodies, Myths and Heroines, at Boulder’s East Window Gallery through February 28, 2024, is a forensically acute exhibition that – in curator Todd Edward Herman‘s words – redirects viewers away from the “pornography of old age” and toward the “lived body” that thrives in the latter stages of life. Each of the ten individual and collaborative artists is represented by just two or three images. The show’s sparseness, however, belies its complexity and impact.

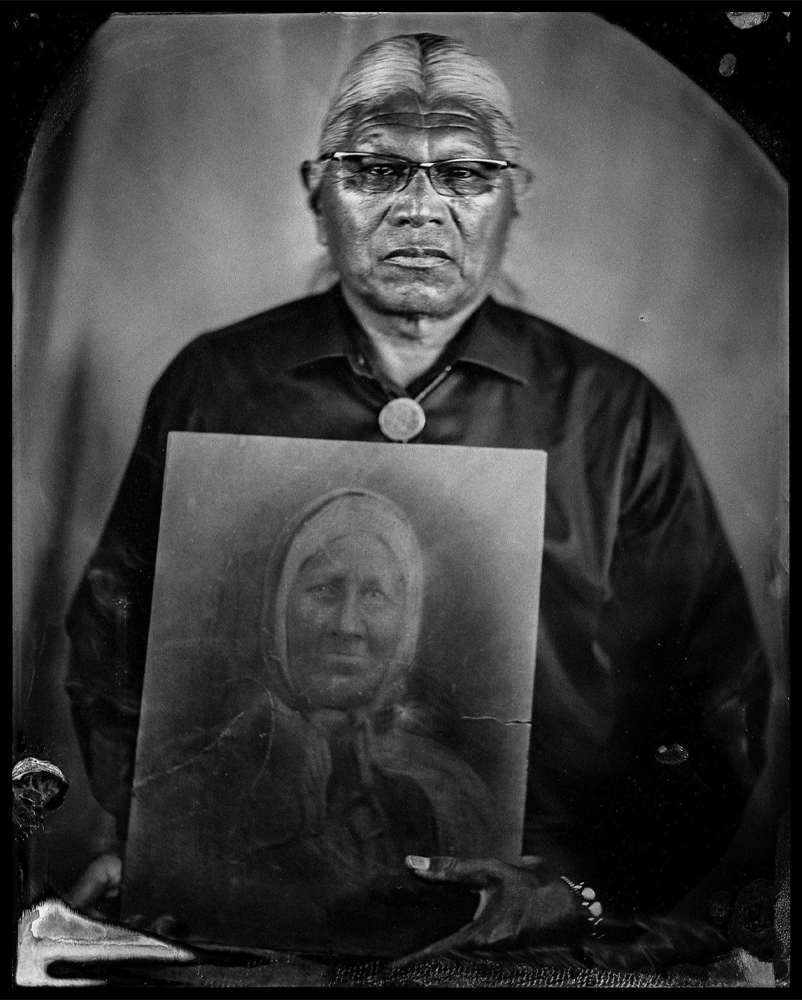

© Will Wilson, John Gritts, Cherokee Nation, 2013

©Roddy MacIness, Incontinence and diapers after prostate surgery. Discomfort and humility, our best teachers, 2022

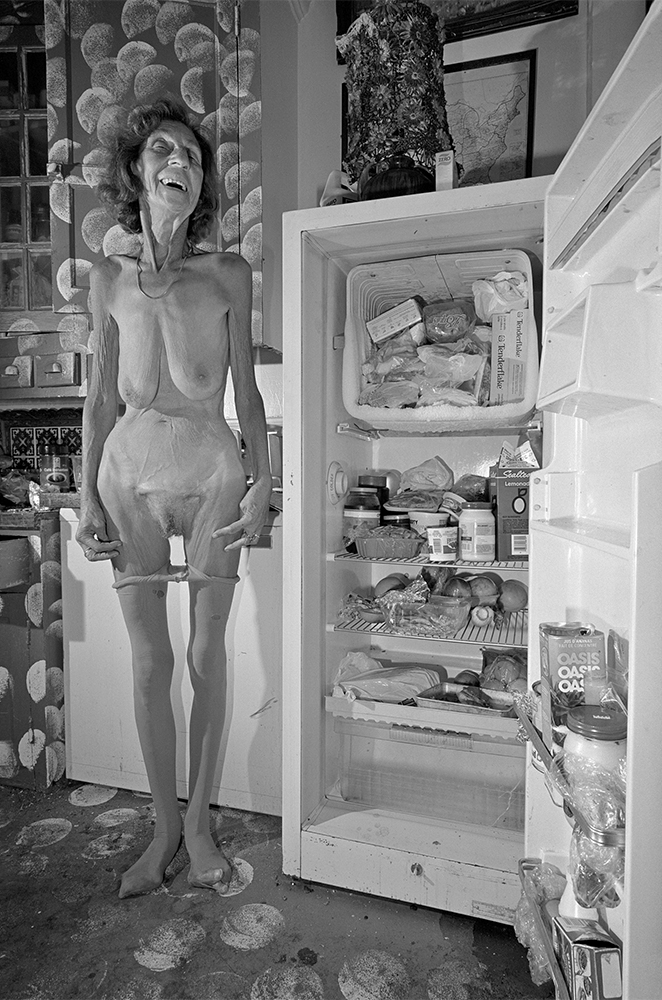

Aging Bodies presents images of elders in the dual context of the body and photography itself. References to family and ancestry recur throughout the exhibition. In Will Wilson’s scanned tintype portrait John Gritts, Cherokee Nation, Gritts holds an ancient photograph of his great-great Grandmother, Dockie Livers, who survived the Trail of Tears. That image is positioned near Roddy MacInnes’s conceptual self-portrait taken in front of Nicephore Niepce’s 19th century Heliograph of rooftops—the first known fixed image made using a photographic process. Next to that, a pair of self- portraits by MacInnes show his cut and diapered body in the aftermath of prostate surgery. This juxtaposition of incongruous imagery should not, but actually does, make sense, especially when one looks across the room to Donigan Cumming’s stark portrait of an emaciated Nettie Harris standing naked in shredded pantyhose next to an overflowing refrigerator. Harris was one among many wrecked people “living on the Titanic,” as Cumming’s subjects have been described.

©Donigan Cumming, Excerpts from Pretty Ribbons: Portraits of Nettie Harris, 1996

©James Hosking, Donna Personna (3 excerpts), 2014

Like Cumming, James Hosking is a photographer and filmmaker whose Donna Personna (3 excerpts) presents a triptych portrait of a veteran drag performer living in San Francisco’s skid-row Tenderloin neighborhood. Hosking adopts three different perspectives by which to show his subject: at home with no make-up; semi-made up, their face fractured by a mirror; and in full drag make up—a stucco-like mask whose illusion of youth fades against a youthful bicep flexing in the background.

Installation view of Aging Bodies, Myths and Heroines, Courtesy of East Window Gallery

©Sherry Wiggins and Luís Filipe Branco, Cleopatra at the Cafe, 2023

In her collaborations with Luis Felipe Branco, Sherry Wiggins inhabits the personas of ancient heroines and goddesses such as Sappho, Aphrodite, Helen of Troy, and Cleopatra to interrogate notions of power and sexuality in older women. She describes her “sixty-something-year-old-white-lady face and body” as being joined with the iconic Egyptian queen, who she presents in two radically different scenarios at East Window. In Cleopatra at the Café, she sits alone in a harshly-lit Portuguese coffee house—a legend out of time and place wearing a gaudy application of make-up not unlike Hosking’s drag queen. In the gallery’s entrance way, a mural-sized reenactment of Jean-Baptiste Regnault’s 1796 painting Death of Cleopatra finds her sprawled bare-chested and lifeless on an opulent daybed.

Installation view of Aging Bodies, Myths and Heroines, Courtesy of East Window Gallery

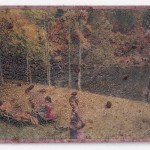

©Mitchell Squire, gucci, muthaf**ka, 2020

Across the central space, a self-portrait by Mitchell Squire echoes her posture. Squire, a robust sixty-plus-year-old Black man, lies naked in a wood, his body festooned with strands of white and gold tinsel. Squire’s acts of “personal anarchy” invoke conflicting associations of celebration and the subliminal history of racial violence against African Americans. In a second image hung in the rear window of the gallery building, he sits cross-legged in a field; bathed in natural light, he wears a bow fashioned out of a plastic bag on his head and a string of decorative lights around his neck.

©Magdalena Wosinska, Old Gays (for the NY Times), 2022

As Herman states, Aging Bodies operates somewhere between two representational tropes—heroic “forever youthfulness” and a more chronic bodily decline that imprisons the youthful soul. The former aspect is accentuated in two color images by Magdalena Wosinska that share the window space with Squire. Like Squire, she has photographed her elderly subjects—both vogueish, semi-naked, white, gay men—in a vernacular style. Their character differences are suggested by their contrasting body language; one, her father, smells a cut rose as he looks deeply into the lens; the other adopts a disconcertingly aggressive gaze as he poses in the shower.

©Danielle SeeWalker and Carlotta Cardana, Ula and Tim Tyler – The Red Road Project, 2013-Present

©Marissa Nicole Stewart, Excerpts from Call Me When You Get Home, 2022

Danielle SeeWalker and Carlotta Cardana’s portraits of Native Americans in their homes are arguably the most traditional works in the show, yet, as with any photographic portrait of Indigenous people in the post “Vanishing Indian” decades, there is an inescapable subtext of the struggle for self-identity and tribal representation. An array of photographs on the living room wall behind Ula and Tim Tyler speaks to a long and rich life together; in another of the show’s many contrasts, Marissa Nicole Stewart also shows a wall of photographs, but unlike the Tyler’s carefully maintained display, Stewart has Dymotaped many of her snapshots with the word “contested” as a commentary on her family’s African American history. She also memorializes her grandmother in a heartfelt portrait placed at the center of a black- and-white triptych (organized by Herman). Andre Ramos-Woodard, in contrast, juxtaposes a simple snapshot of his own grandmother with a picture of a ceramic wall angel to create a simple and elegant memorial to her.

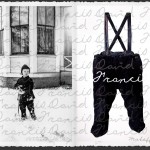

©André Ramos-Woodard, Guardian (Hartense), 2023

Like any good show Aging Bodies raises numerous questions: is this presentation of costumed, naked, deprived, opulent, Black, Native, white, gay, straight, and/or “othered” bodies an alternative vision of aging, or does it actually offer a more honest, conventional representation than mainstream photo essays of, say, affluent retirees in Florida or Arizona? Is it affirmational or its own “pornography of old age” which, Herman insists, is certainly not its intent? Why is it that so much of its imagery is beguiling yet, at its most extreme, disturbing? How is it able to sidestep photography’s inextricable association with death? To an overwhelming extent, the answer to that is found in Herman’s allegiance to the “lived body.” Like many of his exhibitions, Aging Bodies challenges us to look closely, to accept its discomfort, and to celebrate its revelations.

Aging Bodies, Myths and Heroines will be on view at East Window Gallery in Boulder, CO through February 28, 2024. View the gallery guide to learn more about the exhibition, artists, and related programming.

Rupert Jenkins is a writer and editor who lives in Denver, Colorado.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Gary Owens: In the RoomJuly 9th, 2024

-

Ellen Mahaffy: A Life UndoneJuly 4th, 2024

-

Lisa Guerriero: Handle (her) with CareJuly 2nd, 2024