The Hand in Nature, Tyler Green: The Missing Forest

The Hand in Nature: a week of photographs that manipulates how we see and foresee our environment.

Photographs help us process what is happening in the world, and this week we’ll be following photographers whose work inspects humans’ impact on the earth. More importantly, the posts will focus on how each photographer uses their hand in the manipulation of imagery. Many of the photographers’ works curiously demonstrate our history and future relationship with the earth.

Today we will focus on Tyler Green’s photography series, Missing Forest.

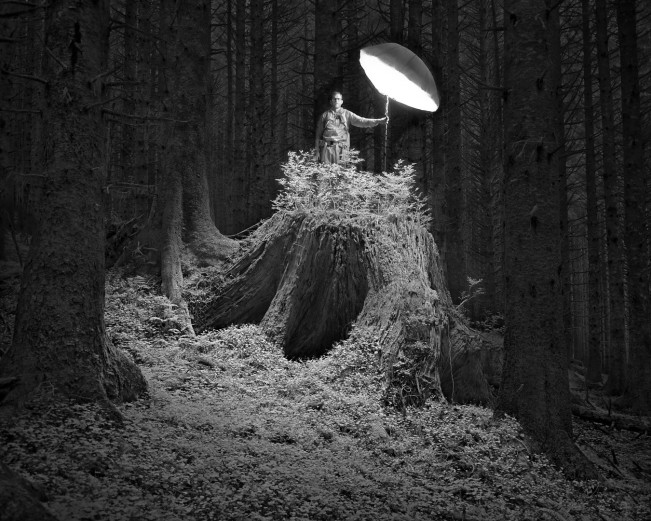

Tyler’s work started with being confronted head-on with what resource extraction looked like while hiking in the Pacific Northwest. He felt a sense of loss, longing, and wishing as he roamed the extracted landscapes. Starting in 2020, throughout the pandemic, Tyler confronted multitudes of large first growth trees. To clarify, these are not small scenes; the stumps he photographed range from six to eleven feet in diameter. He intentionally shows stumps with signs of springboard notches, this being an indicator of a method that loggers used to cut down larger trees. Within his process, Tyler examines what value the trees have and had when living out their existence in obscurity. This query is present throughout all his work and is something he wants to illuminate, and in actuality, through his process, he does.

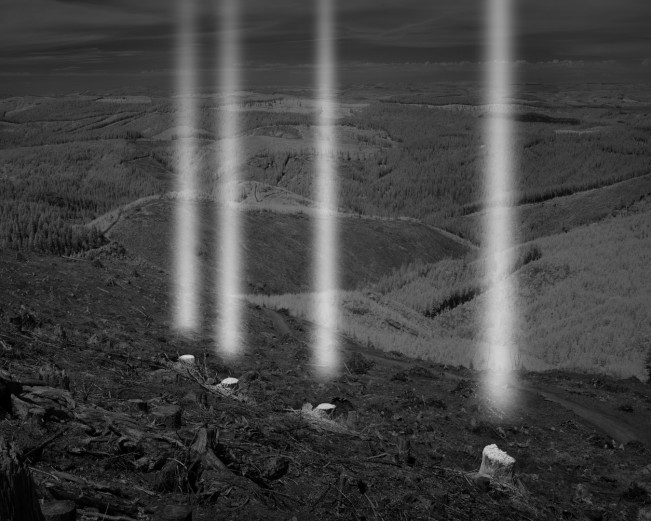

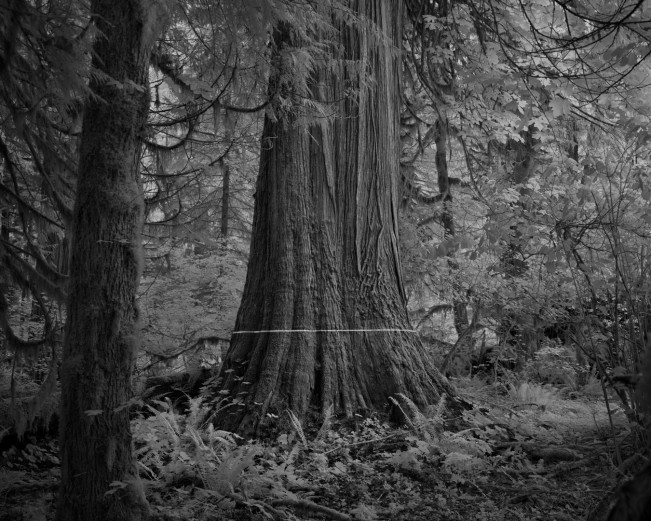

Artificial light is a tool Tyler uses in his most ambitious works that make up the more extensive sub-series of Missing Forest. In his group of photographs called Remnants, Tyler illuminates’ stumps as if they are glowing, allowing them a clear separation from the surrounding trees. In Ghosts, light beams create physical extensions from the stump to the sky. Lasers are used in Incisions, another group of photos, to create a light line symbolizing the physical line where these trees could soon be cut. The result of Tyler’s play with light is poetic and profound; it represents the memories of a past life and has given these unacknowledged trees a stage when they usually go unseen.

In the traditions of black and white film photography, with its timely factual quality, it is easy to assume that Tyler is presenting the scene precisely as found. Tyler, in actuality, uses digital to deal with the multiple technical complications in lighting and editing. One key thing to note is that he shoots with his digital camera limited to the infrared spectrum of light (850+ nanometers wavelength). Infrared light is monochromatic by nature and conforms to black and white when the color data is removed, making the lifeless elements stand out. The separation of darks and lights adds to the mysterious and somber qualities of the photos. The infrared results most influence the Remnant stumps, where the skeleton quality is more pronounced.

Tyler is not only a photographer; he has a background as a data analyst, which also speaks to the other processes of his work. He spends a lot of time learning about the history of these wooded landscapes. Tyler shares the information he collects. Along with his imagery, he includes old growth maps and satellite imagery of the regions that he explores. Seeing these landscape transitions in such a short time is eye-opening but adds a more substantial weight to what we are viewing in Tyler’s photographs. For example, Tyler shares satellite imagery of the Tehaleh Community, a newly developed housing community in Washington that is particularly alarming as the landscape shifts within a few short years. Looking up this community, one will find a fancy website marketing upscale homes that are immersed in the beautiful forests of the Pacific Northwest. The satellite imagery gives us a birds-eye view of how we manipulate this landscape to be near it.

There are quieter works that make up the Missing Forest series. In his series Clearings, Tyler shares subtle and beautiful shots of large, working forests with signs of resource extraction. In his group of photos called Reverence he takes photos that display how we utilize trees within urban and rural spaces. These two groups of photos show us two contrasting visuals the trees that we will never know and the trees that we have curated into the human landscape. Nature is essential to us; we like to admire it, but usually within a controlled space.

Seeing the physical force of a human’s hand on the landscape throughout the series reminds us of our dire relationship with trees. Tyler says he is not making this work to point fingers – but to help himself and his viewers process their relationship with nature.

Tyler’s Missing Forest is not the first or the last artwork that will be made about our altered landscape. Sadly, there will be more. But Tyler’s images poetically ask us to address it face-on. It is easy to connect Tyler’s work and the work of Emily Carr, a Canadian painter of the early twentieth century whose work also focused on the ecological issues of the logging industry in the Pacific Northwest. A quote from Emily Carr’s journal entry during the 1930’s becomes eerily relatable when viewing Tyler’s work.

“There’s a torn and splintered ridge across the stumps I call the ‘screamers.’ These are the unsawn last bits, the cry of the tree’s heart, wrenching and tearing apart just before she gives that sway and the dreadful groan of falling, that dreadful pause while her executioners step back with their saws and axes resting and watch. It’s a horrible sight to see a tree felled, even now, though the stumps are grey and rotting. As you pass among them, you see their screamers sticking up out of their own tombstones, as it were.”

Emily Carr, Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1966), 132–33.

©Tyler Green, Missing Forest, Northrup Creek Ridge I, six feet two inches in diameter lower, two feet nine inches in diameter upper

Look at all of Tyler’s work on his website and follow him.

Follow Tyler on Instagram at @tylergreenphoto.

Tyler’s Bio:

Tyler W. Green (b. 1985) is a photo-based artist whose work reflects his interest in the relationship between humanity and the natural world. By confronting the value of progress and challenging the perspective that humankind is separate from nature, his photographs explore themes concerning social and ecological equity while raising concerns about environmental degradation and the inherent value of natural places.

Green completed an Associate of Applied Science in Audio Production at the Art Institute of Seattle. He worked as an assignment photographer for the Albuquerque Journal and staff photographer for the Artesia Daily Press in New Mexico where he received multiple awards from the NPPA, Associated Press and New Mexico Press Association.

Green’s photographs have been exhibited in both solo and group exhibitions at venues including Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR, the Art Center in Corvallis, OR and the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, NM. His photographs are held by the Portland Regional Arts & Culture Council in Portland, OR and other private collections.

He currently resides in Albuquerque, NM after relocating to his home state from Portland, OR in 2022.

Sarah Knobel is a photographer, video and installation artist that works with everyday items to find new ways to identify our relationship with ideas of the natural, artificial, beautiful and repulsive. Her work has been featured in exhibitions nationally and internationally, which includes Miami, Seattle, Portland, Kansas City, Washington DC, Germany, Belgium, Korea and Greece. Sarah holds an MFA in Photography from the Design Architecture Art and Planning Program at the University of Cincinnati and a BFA in Studio Art from Texas State University. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York.

Follow Sarah on Instagram at @sknobel.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Patricia Howard: Unknown AncestorsFebruary 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025