Clement Valla: The States Project: New York

New York-based artist Clement Valla takes a bit of a different approach to looking at imagery – in these works, Surface Survey and Wrapped Terracotta neck-amphora (storage jar), he is interested in how imagery is generated through technical processes. Images that are created for some other function, working within a system that is moving towards a specific utilitarian result: in this case, 3D scanning for archiving and documenting antiquity. The images and sculptures that are featured here are all taken mid-way through the process – you are looking at imagery and forms that were never meant for the human eye to see. These images are but information that has yet to be processed by additional computational steps that would result in the final realized document (a fully textured 3D model). Valla wishes to reveal the technological eye by pulling imagery from this complex process. I was able to ask him a few questions about his works to help further introduce the concepts and processes behind what he does.

Clement Valla is Brooklyn based artist. His recent solo show Surface Survey at Transfer Gallery in New York was an Artforum Critic’s Pick. His work has also been exhibited at The Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis; Museum of the Moving Image, New York; Galleri Thomassen, Gothenburg; Bitforms Gallery, New York; Mulherin + Pollard Projects, New York; XPO GALLERY, Paris; DAAP Galleries, University of Cincinnati; 319 Scholes, New York; and the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum, Milwaukee. His work has been cited in The New York Times, The Guardian, Wall Street Journal, TIME Magazine, El Pais, Huffington Post, Rhizome, Domus, Liberation, and on BBC television. Valla received a BA in Architecture from Columbia University and an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in Digital+Media. He is currently an assistant professor of Graphic Design at RISD.

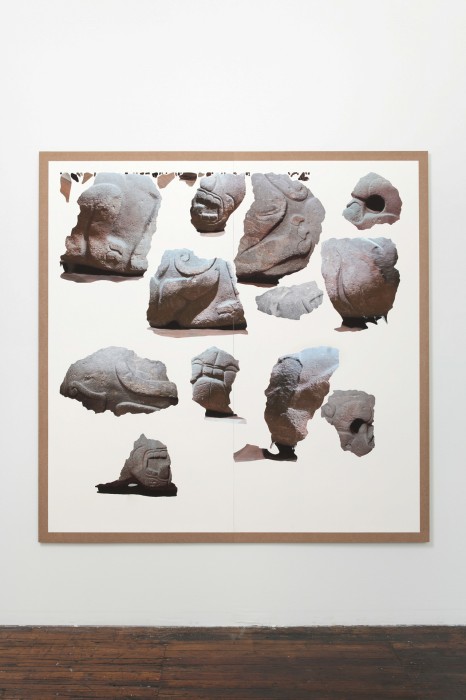

Surface Survey

Surface Survey is comprised of digital prints and 3D printed sculptures, structured around concepts of archaeology, computer software, meaning-making, and images that are not meant for human consumption.

To explore these themes, Valla collects digital artifacts produced by software that turns photographs into 3D Models. The arranged fragments are left untouched, exhibiting the software’s process as-is. The work is comprised of both 2D images meant to be processed by the computer (but never seen by humans) and 3D printed fragments that indicate how the software pieces the shapes together. Valla ‘s subjects are varied: from sculptural antiquities he photographed in the Metropolitan Museum’s collections, to contemporary ephemera, to 19th Century inventions. The work uncovers subtle shapes and textures that illustrate these objects in unexpected ways and cast a new light the algorithms that digitized them.

Valla’s work reflects on the human potential of meaning-making in unfamiliar, software-created images. He is interested in the relationship between what a computer reads and the distance from what a human will understand. This interest extends to the language of computer image-making, suggesting an archaeology of computer software, whose extractions reveal the computer’s systematic logic.

In your series surface survey, it seems as though you are interested in exploring the way in which the technological eye sees and understands our surroundings. Your work points to the fact that the technological eye, in fact sees in a completely different manner than the human – highly quantitative and incredibly organized. I find it interesting that man-made technology meant to describe space does so in a way that is so different from the way the human senses do – almost in a way that suggests perhaps our eyes are inadequate to do so. What is important to you about examining the differences between the ways humans see vs. the way technology sees?

What interests me foremost about the images that I find and present is their unintentional aesthetic. In many of my works including Surface Survey, the images are technical images that are part of a larger process (in this case, the images are texture maps that are used as part of the 3d modeling process). The images are produced by one piece of software, the scanning software and are intended to be parsed by another piece of software to display the 3d model on a computer or in the browser. So the images in Surface Survey are part of this chain of operations (Harun Faroki calls these kinds of images ‘operative images’). However, they are never meant to be seen by humans – they are not images in the traditional sense of human-to-human communication. As such, their meaning and interpretation relies on a different set of structural principles – a technical, computer-based one – rather than say composition, color, semiotics, etc… So the engineers and programmers who develop the software that generates these images do so with primarily technical concerns rather than aesthetic concerns (though undoubtedly some unconscious aesthetic bias finds its way in). In this sense the images are unintentional – they are the result of a technical operation rather than an aesthetic decision-making process. By presenting these images as art-works, I am essentially pulling them out of their normal flow of utilitarian operation, and putting them up for humans to consider aesthetically. Hopefully this done a couple of things: first it sheds some light on the computer vision operations themselves, giving us a glimpse of how these technical forms of vision work, and second it allows the images to circulate as strange aesthetic objects.

In your piece Wrapped Terracotta Neck-Amphora you present a form that is similar to the source that was captured by the 3D scan that is then wrapped in a cloth that has the image printed on the surface that was captured by the 3D scanning process (what process was this exactly?). The work seems to critique reproduction of historic artifacts both in the context of the museum format and the digital format. What is it that fascinates you about the ways in which antiquity is reproduced?

The process: I use photogrammetry software (like 123D Catch) that produces 3d models from photographs of an object. Once I have captured a 3D model of the object, I do two things to output this model physically. First, I have the model manufactured through CNC routed foam, at 1:1 scale. This foam replica is a duplicate of the volume and contours of the original source that was scanned, but does not contain any of the texture/color/detail of the original. The second thing I do is to flatten the surface of the 3D model into a printable 2D image. This gets printed on linen, and then wrapped around the foam sculpture – in a way this is ‘skinning’ the foam sculpture. This process produces something that is in between a printed image and a sculptural object. Because the ‘2D’ nature of the linen print remains evident in the final form, and because I often display a 2D print along with the works.

It’s this vacillation between image and object that interests me when I work with objects in museums. The objects in these collections functioned differently as objects in their original context from which they were removed from. In museums, they begin to read more as ‘image’ – as in a beautiful thing to look at rather than a functioning object. In this way, artifacts become sculpture. I’m interested in pushing this one step further – to where sculpture becomes image. This final transformation, from sculpture into image or digital object is happening constantly now in collections around the world. I’m really curious about how it will transform the objects, and re-circulate them in different contexts.

Wrapped Terracotta neck-amphora (storage jar)

Wrapped Terracotta neck-amphora (storage jar) is a sculpture that is neither an object nor an image. Valla used digital 3D capture to reproduce a 7th Century BC Greek amphora on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To highlight the artifacts produced by computer vision the completed reproduction is broken down into its constituent parts: a flat image wrapped around a 3D volume. The resulting sculpture echoes the packing of objects for storage and shipping, transitory moments when only an object’s image is accessible. The image ends up serving as a surrogate for the sculpture underneath.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Jordan Eagles in Conversation with Douglas BreaultDecember 2nd, 2024

-

Ryan Arthurs in Conversation with Douglas BreaultMay 19th, 2023

-

Mariah Robertson in Conversation with Douglas BreaultMay 17th, 2023

-

Clement Valla: The States Project: New YorkMay 30th, 2015