Mary Beth Meehan: Seen/Unseen

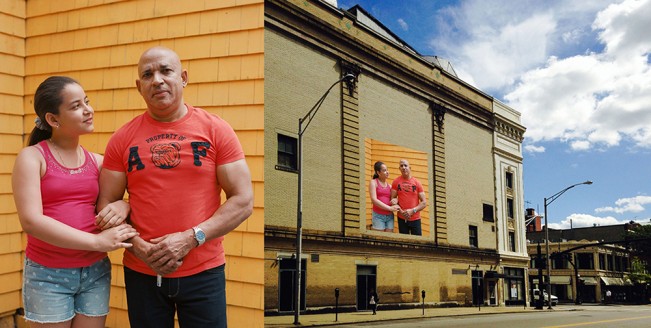

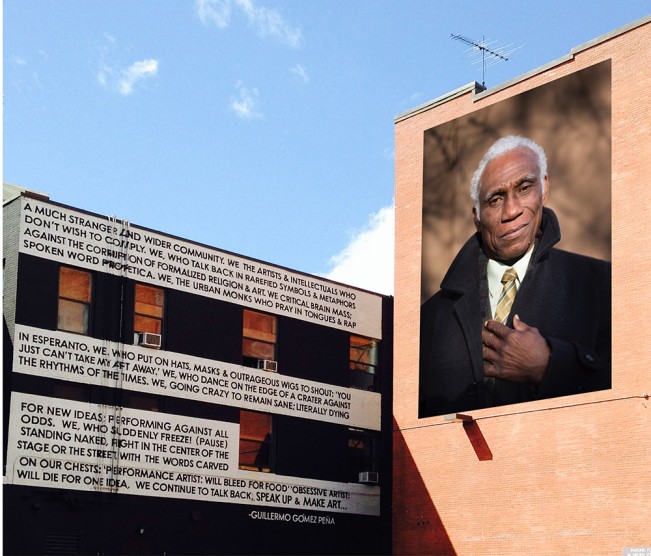

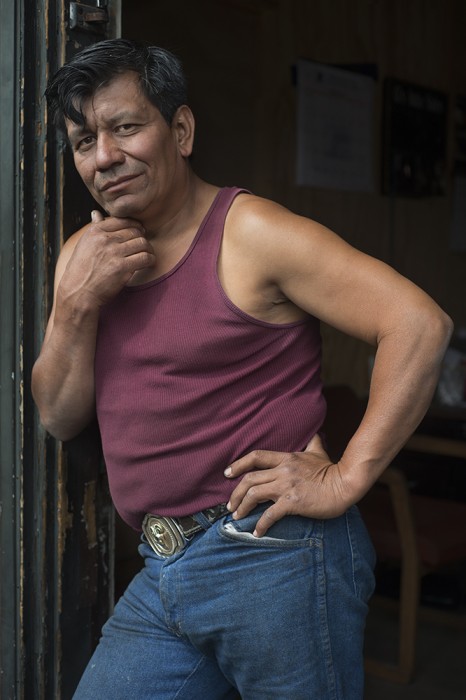

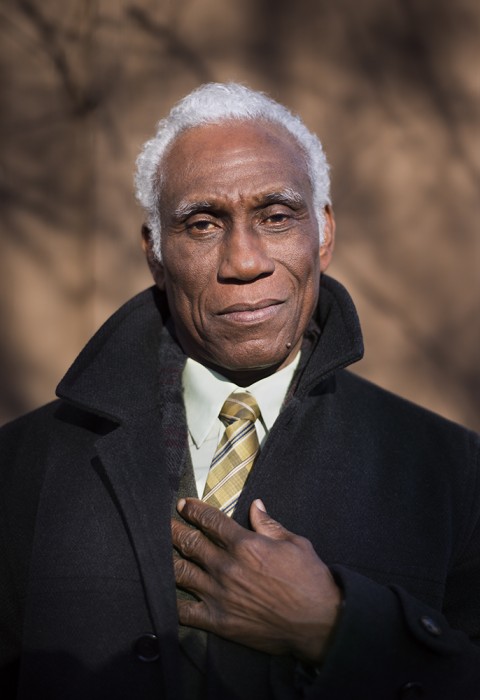

This weekend during the Providence International Arts Festival, photographer Mary Beth Meehan brings large-scale portraiture to the city of Providence, Rhode Island. Mary Beth has long been a sensitive and acute seer of the ordinary, and she uses her photography to create connections among people that may be obscured by conceptions of economics, politics, or race. Seen/Unseen: Providence is a project that crisscrosses the city’s neighborhoods documenting people in a way that forces one to stop and take notice. Mary Beth’s photographs reveal the essence of who makes up a city and celebrates individuals that are at the heart of a community, real people that often get overlooked or are “unseen”.

Providence will display eight large-scale prints adorned on buildings along the Washington Street Cultural Corridor. The installation begins facing Empire Street at Trinity Rep and continues down Washington Street. The Providence City Hall will also feature a larger exhibition of portraits, along with text from Meehan’s “Seen/Unseen” blog, on which she documents the creation of the project. On Thursday, June 11, at 4pm, there will be a lunchtime Public Conversation at the RISD Museum and on Saturday, June 13th at 6 p.m., a Print Exhibition will open with a reception at Providence City Hall.

Her recent project, City of Champions, responds to her hometown of Brockton, Massachusetts, a post-industrial American city. The series was awarded a “Crisis, Community, and Civic Culture” grant from the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. Twelve images were produced as large-scale banners and displayed on buildings in downtown Brockton. The installation sparked community-wide conversations about immigration, evolving urban identities, community dislocation, and the possibilities for social change.

Meehan’s work has been published in 6Mois Magazine and Le Monde (France), The New Statesman (U.K.), Bird Magazine (Japan), and featured on New York Times: LENS; it has been shown in solo exhibitions at Smith College and at the Griffin Museum of Photography, was exhibited at the Ring Cube Gallery, Tokyo, and the Photographic Resource Center, Boston, and was featured in two New England Photography Biennial exhibitions at the Danforth Museum of Art. Her work has received financial support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts.

A former staff photographer at The Providence Journal, Meehan has since contributed to The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and The Washington Post, and received the 2012 Rhode Island State Council on the Arts Fellowship in Photography. She was nominated twice for the Pulitzer Prize and has been honored by Pictures of the Year International and the National Conference for Community and Justice.

Meehan graduated from Amherst College, in Massachusetts, and earned a Master of Arts degree in journalism at the University of Missouri. She currently teaches Documentary Photography at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and directs the “Documenting Cultural Communities” program at the International Charter School, in R.I. Her approach to teaching is motivated by many of the same concerns that drive her photography: to help students explore the cultural identities of themselves and their neighbors, to illuminate aspects of the immigrant experience in the United States, and to make people more visible to one another, as human beings.

In the course of my career I have often been drawn to photographing in situations where I felt there was some disconnect between the public perception of a place, or issue, or community, and the reality of what it felt like to be of that community. I grew up in Brockton, Massachusetts, a place largely characterized in the media by its poverty, crime, and social dysfunction. And yet I experienced that place – both as a kid growing up there, and later as an adult photographing there – as a place of incredible richness, complexity, and beauty, all of which coexisted with the truth of its problems. It was painful; it still is painful. So, for example, in the case of undocumented immigrants, I was hearing them described in the public debate as criminals, people we should fear and we should expel, at the same time that I was meeting them, and experiencing them for myself as dedicated parents, workers, churchgoers, contributors to our community. And I was realizing that they had made very difficult decisions to come here on behalf of their own lives and their families. It made me wonder about the people who were protesting – if they had been faced with similar life circumstances, would they have made similar decisions?

Photography is what I love, first and foremost. I love the process of meeting people, being in situations that are new to me, trying to make an image that is, in some way, true to the situation, as well as emotionally resonant and aesthetically beautiful, or arresting, or compelling. So it’s my little thing, my little contribution. And I love applying this thing of mine to this problem that I see, which is people not really seeing each other clearly. I try to use my photography as an intervention of sorts, as the parting of a curtain, to say “I’m going to lift this curtain here (as in the example of my “Undocumented” series) onto the rooms that these people are living in. I’m going to try to show you something about the person that you think you know, and then I’m going to ask you to revisit your assumptions and see if they are still in line with what you’re seeing. And if they are not, can you shift your view, just a bit? Can you somehow come into contact with something more human about this person, or this situation, than the current debate has allowed in?”

Maria DeCarvalho, a dear friend of mine, just emailed me an article from this week’s New Yorker. The subject line of her email read: “Must read immediately.” Over the years she and I have had many conversations about photography, and people, and what gets in the way of our seeing one another clearly, and the dangers involved when our own subjectivities get in the way of our seeing each other clearly. The article was about the mass murderer in Norway, and how, on some basic level, he had never felt “seen” – by his parents, or by his community, and that this was a fundamental wound to him. The article also describes how, in the Iraq war, soldiers found it difficult to kill another human being; the presence of a person, with a face and eyes that they could look into, inhibited their ability to kill. So in training they were given targets in which the faces were replaced with a bullseye or some other de-humanized image; in that way they convinced themselves that they were killing something less than human, the enemy was now faceless, anonymous, something less than human. Once that dehumanization had been achieved, they could kill.

There is something about a photograph when it arrests the gaze and engages the viewer, that makes the person pictured, and the interaction between the viewer and the viewed, impossible to deny. In Brockton, I did a public installation of photographs somewhat like Seen/Unseen, which is about to be launched as a public installation in Providence. Afterward, I interviewed people in Brockton about what it was like to live with the photographs, which were installed in the cityscape for a year. People talked about how, in the busyness of their daily lives, they were apt to pass right by people, engrossed in their own thoughts and projects, and not ever engage the person or even wonder about them. But when the photograph was there, in their faces, and over time, they began to wonder about the person, to think about what they were experiencing, what they might have in common. And in some small way, it was transformative for them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026