Peter Happel Christian: The States Project: Minnesota

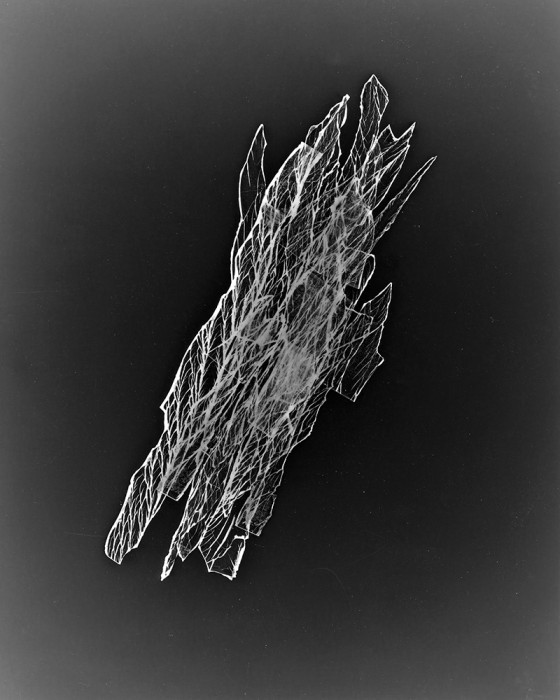

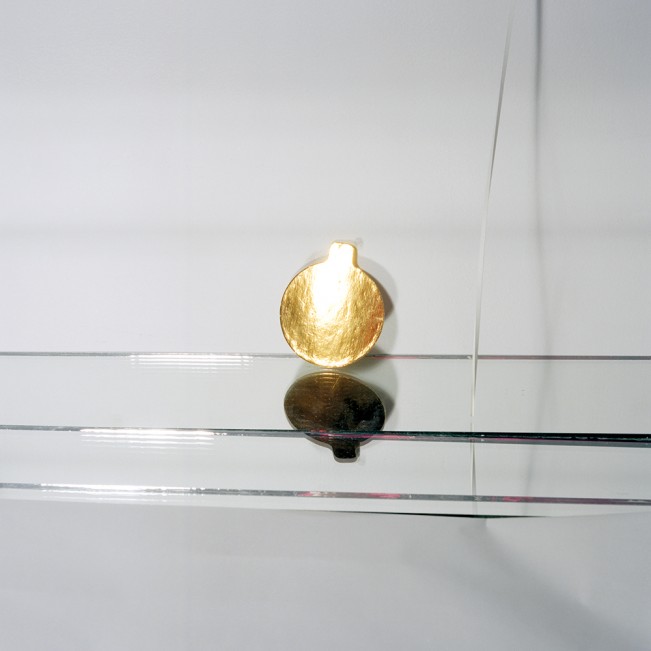

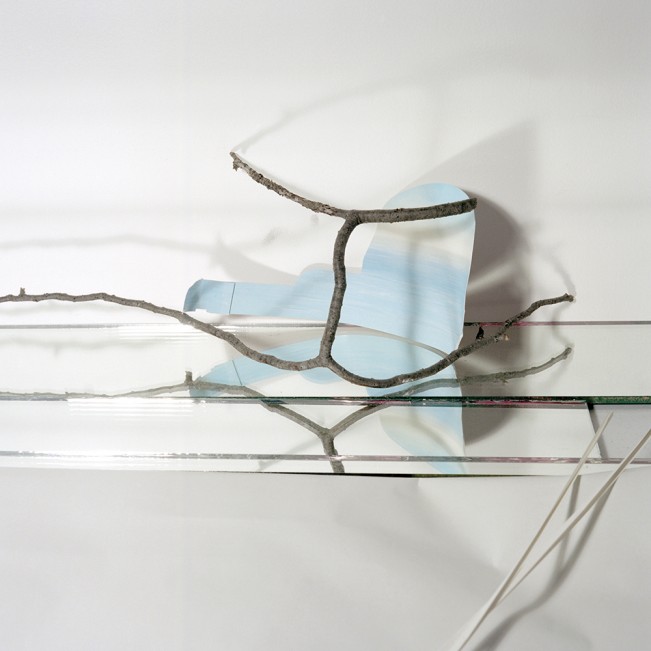

Since we began The Lenscratch States Project in April we have featured nine states that all brought unique bodies work to the table. The participating curators have all granted us insight into what the states have to offer, both in art scene and in the quality of work being made at this moment in time. This week Peter Happel Christian with be representing Minnesota, our tenth and final state of the year. Peter’s body of work The Sword of the Sun shares a different answer to exploration of the recognizable space around himself. The ideation of this nondescript place colorfully illuminates the complexities of time by toying with the perceptions and planes of what one singular place can be. His work is tangible because the objects he uses are relatable. Sticks, mirrors, old floral sheets, and other various household paraphernalia allow an entry point into the work, though, quickly things become not quite what they seem, and in this peculiar environment material becomes essential to the marks that are left behind.

Peter shares his perspective of being a Minnesotan photographer:

I’m a transplant to Minnesota (via Iowa/Oregon/Arizona/Ohio) so my perspective might be less deep than another person, but I’ve lived here long enough that I think I can answer that with some sort of clarity. The standard license plate in Minnesota announces it as the Land of 10,000 Lakes, but it also seems to be the Land of 10,000 Grants. Minnesota has an incredible amount of funding opportunities for artists through both public and private sources. There is a lot of support for the arts and being a photographer here means you have access to money that can help you take risks in new work and also help you see a project through to the end in the way you imagine it. For me, that is something unique about Minnesota. Don’t get me wrong, applying for grants are a ton of work and are never a guarantee. The process of applying for funding over and over has made me a better writer which has given me a strong sense of what my work is about or, better yet, what my work could be. There is also vast diversity in landscapes, economics, politics, and cultures in the state which is really engaging – I think Minnesota presents a certain image of itself to the world, but it is such a complex place when you start to peel back the layers. In that way, being a Minnesota photographer means there is enormous potential to connect to various people/places/ideas to make work about and secure funding to do it. Also, it does get really cold in the winter, but nothing a sturdy down coat can’t solve! It took me two years to learn that.

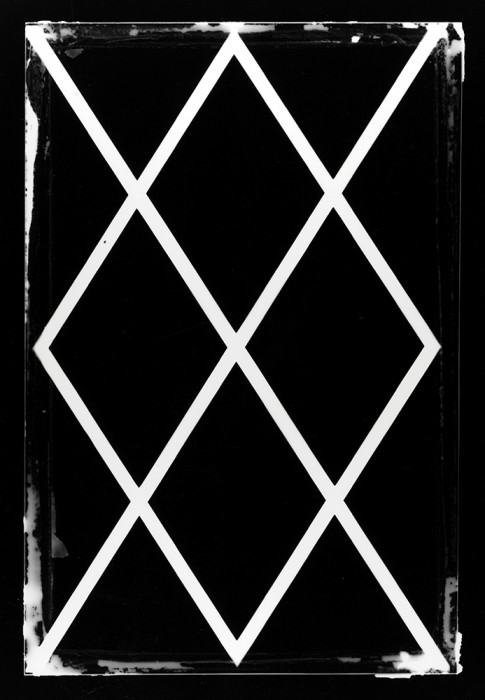

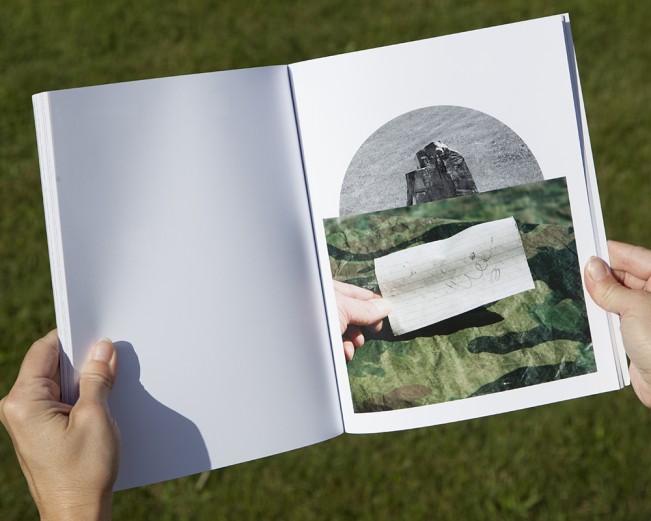

Sword of the Sun draws its title from a short story by Italo Calvino. In the story, an elderly man swims in a nameless sea at sunset while contemplating the spangled shape of the sun on the water around him. From the edge of Calvino’s imaginary sea, the artist made pictures in and around the landscapes of his home in central Minnesota. A long history of granite quarries and a lingering pioneer spirit serve as backdrops for an experimental narrative about time and place near the edge of a nameless pond. As time skids forward — dragging history, impressions and the things of these photographs with it — one begins to realize that the sword of the sun is the sharpest edge in the world.

I see that you grew up in the Midwest and even returned after grad school. To what extent does this region play into your practice?

I’m originally from Iowa and I strongly self-identify as a Midwesterner. I like big skies and open space. It took me leaving the Midwest to realize how much I value it. I loved living in the American West too, but the pull back to the middle was strong. The region doesn’t play a huge role in my studio practice – I don’t explicitly make work about being in the Midwest – but I do make work about where I live. I think of my yard, garage and landscapes around my home as extensions of my studio and if that space is in the Midwest then the region has a very literal role in my practice as a backdrop for photographs. Two recent projects, Half Wild and Sword of the Sun, connected to the literal place and space of where I live, but in each project I tempered the provincial narratives with much bigger ideas or more universal sentiments like what it means to love the idea of something or how we measure and understand the passage of time.

Your work tends to live as book or installation — could you elaborate on why you stray from the traditional framed photograph?

Sure. I have two answers for this question.My first answer is philosophical: I might have a tacit aversion to the traditional framed photograph as a primary mode to make my own work. I understand photography as a medium in eternal flux; it has never been one static set of materials for very long and more interestingly for me, its ability to drum up various meanings depending on its context, use, or scale makes me want to work with it in ways that can speak to this frenzy of references. I like thinking about photography as always in relationship to other things or what it is as a symptom of the process that created it; not an isolated object on the wall under glass and in a frame. A book is a format that lets someone have a tactile experience with pictures at an individual, varied pace of looking and contemplation. That’s interesting and important to me. Installations require that pictures are examined in relationship to objects and the space of the gallery; photography as a component of a larger field of ideas and materials. That is also interesting and important to me as an artist.My second answer is much more practical: I have many framed prints from past exhibitions in storage in my studio. A couple years ago I looked over this collection with a bit of frustration. It represented so much time and energy and money and here it all was – staring at me collecting dust. I still frame work for exhibitions, but it is now on a smaller scale and not the exclusive way I present prints any longer. If a certain body of work or project calls for traditional framing then I am all for it. But I have moved away from this way of presenting my work and have had much more fun and critical engagement with my work since then.

Sword of the Sun has a seemingly conceptual narrative, using objects and processes that I imagine have allegorical significance. Can you tell us a little more about the short story and how it may have inspired this body of work?

Well, to be clear, the body of work wasn’t exactly inspired by the story, rather I reached to the story as a way to help frame the nature of the work I was making. Over the last few years I’ve been trying to work more intuitively and reconnecting with the Calvino story was a symptom of intuition. The short story, The Sword of the Sun, is in the book Mr. Palomar, by Italo Calvino. I have loved Calvino’s writing since I was a teenager and a book of his has never really been out of reach since then. Mr. Palomar is a collection of stories and observations from the perspective of an elderly man. In The Sword of the Sun, one reads the internal monologue of Mr. Palomar as he swims in a nameless sea at sunset while contemplating the spangled shape of the sun on the water around him. He wonders if the sun is there for him alone and quickly realizes that everyone must think the same thing at some point in their lives. He also considers big existential questions about humans and their connection to nature and the world at large. I had read and reread this book over the years so it was on my radar as I was making the work in Sword of the Sun. I connected it to the work primarily because I live near a nameless pond and would pass it every day while driving, on my bike or out on a run. I wondered about its history and discovered that it is part of an abandoned granite quarry from the mid 20th century. I drew a parallel between this pond in town and the sea that Calvino writes about. I realized I could use this old, nameless quarry pond as a place of contemplation and a site to broadly think through the idea of time and how it is measured.

Allegory is a constant in my work – I often end up photographing something because I find it to have either a personal meaning or I recognize it as having the potential to speak to something much bigger than any value I assign it. For instance, there are a lot of sticks in the book – all of those sticks were pruned from a lilac bush in my yard. My oldest son, Henry, helped me do this and to make it more exciting for him we looked for the letter “Y” which he knew was the last letter of his name. But if a “Y” shaped stick is flipped it starts to look like a version of a divining rod which has a beautiful mythology around the idea of finding things in the ground such as water, gemstones, or graves. And the title of the Calvino story has a strong photographic metaphor for me. Photography acts as a sword of the sun in that it slices time into small increments so we can hold still a subject of interest. In this way, my book, Sword of the Sun, speaks to the contemplative drifting of the mind as well as to the nature of photography and its ability to dissect time.

I noticed that in the exhibition Sword of the Sun explores the utilization of sculpture, found object, and alternative presentation, something that I think translates to a book presentation very well. Besides obvious spacial relationships, how is this work functioning differently between exhibition and book?

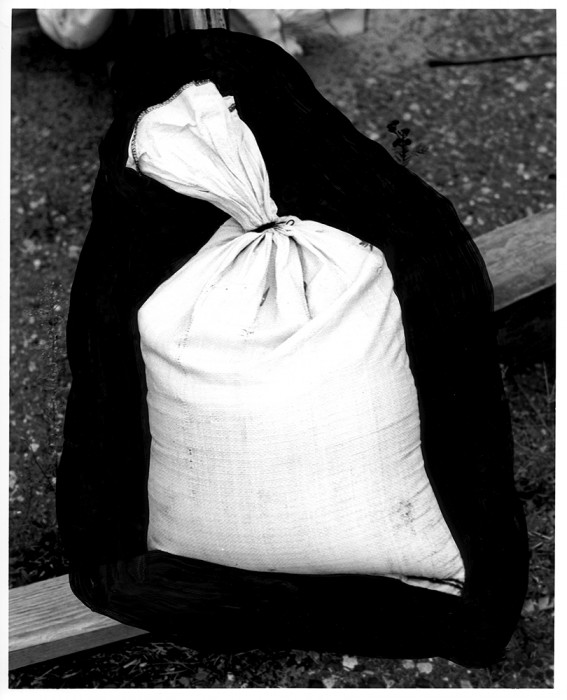

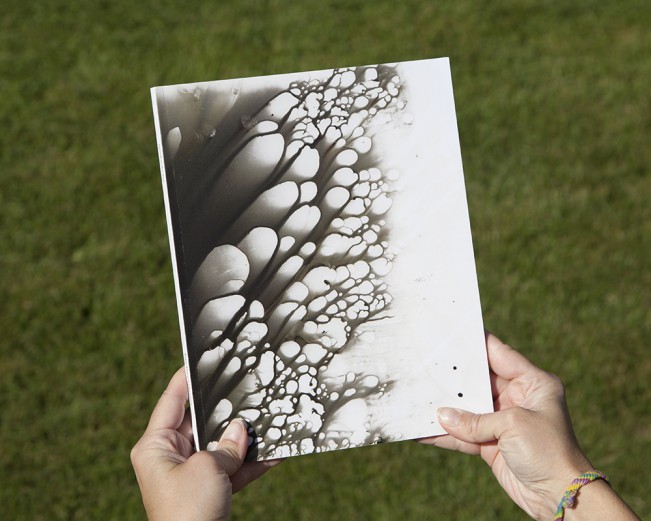

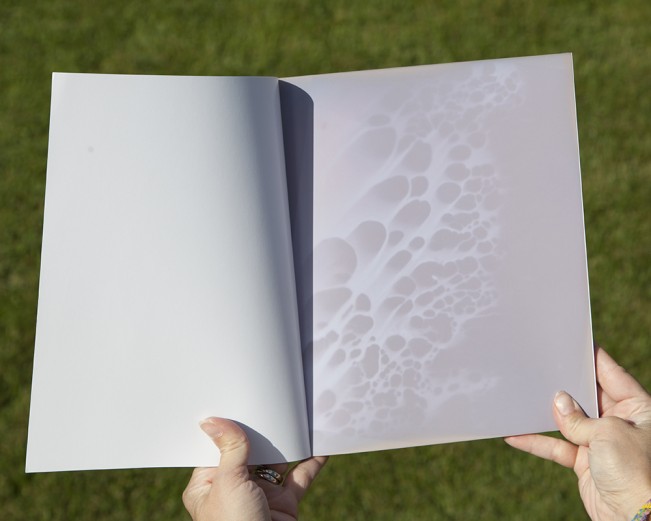

Thanks. A main part of the exhibition was the installation of two table pieces where each had an array of objects, pictures and studio debris arranged on the table top surfaces. I call these table pieces “Infinite Field” and have made five of them now. On each table were also stacks of pictures and printed matter. I used this instance of stacking or piling pictures as a way to begin the making of the book. Initially, I was really interested in translating one of the table pieces to the format of the book and wondered what that would look like and what it could feel like. From there, I made many more pictures and tuned into the nameless pond near my house.The book is more specifically about the landscape near my house whereas the exhibition, which came earlier, was a broader capture of time and space. One piece in the exhibition, Once Around, captured a year of time in the form of 365 sheets of darkroom paper, bundled together, and placed on a cedar pallet in my backyard from January 1 – December 31, 2013. There is no specific image recorded of that year, but time and weather accumulate in the paper and transformed it into an object that can speak to the ways in which photography can never really capture what we want it to. At the end of the day, its no more than an image on a screen or piece of paper. I carried a sense of this sculpture over to the end pages of the book. The book begins and ends with a sheet of unprocessed darkroom paper that slowly records the cover images in real time. Once the reader understands what is happening and looks at the latent image of one of the covers the act of looking exposes the paper more and accelerates its disappearance. To look directly at the image is an act of erasure – the more you look the quicker it will disappear. This idea, as a beginning and end to the book, captures the fleeting nature of time and calls up the desire to look. I think this detail would be tricky to pull off in an exhibition and have the same effect.

Are you currently working on any new Minnesota related projects?

I have a complex project in the works that revolves around an abandoned, water-filled granite quarry that is within the walls of a prison yard here in St. Cloud. Legend has it that prisoners worked the quarry to build the granite wall that would then imprison them. Apparently, the prison wall is the largest granite wall in the US and the only one built entirely by penal labor. I’m interested in all the socio-political layers of this wall and the resulting hole in the ground. I’ve talked with a writer about collaborating on this project, but it’s a slow process and one I have to be very deliberate about.

Finally, describe your perfect day.

My perfect day would begin with a slow wake-up on a sunny day and drinking a really, really good cup of coffee on my front porch while reading a book. It would start that way and then it could go various ways, but to be a perfect it would have to include the following: family-time using magic teleportation to the mountains for a hike and the ocean for exploring tide pools, a tasty lunch of somewhat healthy food, coffee/cookie break (gotta have one of those!), wandering around a forest in the north woods collecting stuff, a good run in the afternoon after quality time in the studio, a trip to a brewery for dinner with new and old friends and then camping in cool weather with my family. Also, on this perfect day I’d invent a way to add six hours to every day. I always want to do more than there is time to do it.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ben Moren: The States Project: MinnesotaDecember 12th, 2015

-

Pao Houa Her: The States Project: MinnesotaDecember 11th, 2015

-

Ryan Aasen: The States Project: MinnesotaDecember 10th, 2015

-

Hillary Berg: The States Project: MinnesotaDecember 9th, 2015

-

Eric William Carroll: The States Project: MinnesotaDecember 8th, 2015