Hannah Schneider and Kate Stone: How We End.

The poignant and witty book, How We End., takes the reader into the private thoughts of an anonymous narrator. While reading through the stories, I frequently found myself laughing and then immediately feeling sorry for the narrator and sorry for the guy. That back and forth kept me interested and feelings of pensive sadness followed me throughout. It’s about not getting the whole story.

Hannah Schneider is an LA-based writer. She studied fiction and received a BA from Bard College where she met Kate Stone. They lived together in a house where squirrels nested in the walls for the winter, which drove them insane. She now spends her time writing television and talking to anyone who will listen about the merits of menstrual cups. Her latest pilot, “STILLWATER” was acknowledged as one of the best unproduced scripts of the year on the 2015 Blood List.

Kate Stone is a Brooklyn-based artist who dreams of working in demolition if only just to prove that she can. She grew up in a creepy old house with stone floors, which definitely has everything to do with everything. She enjoys whiskey and breaking things (especially hearts). She earned a BA from Bard College and an MFA from Parsons the New School for Design. She was a recipient of the Tierney Fellowship and her work has been exhibited at The Center for Photography at Woodstock, bitforms gallery, FiveMyles, Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, among others.

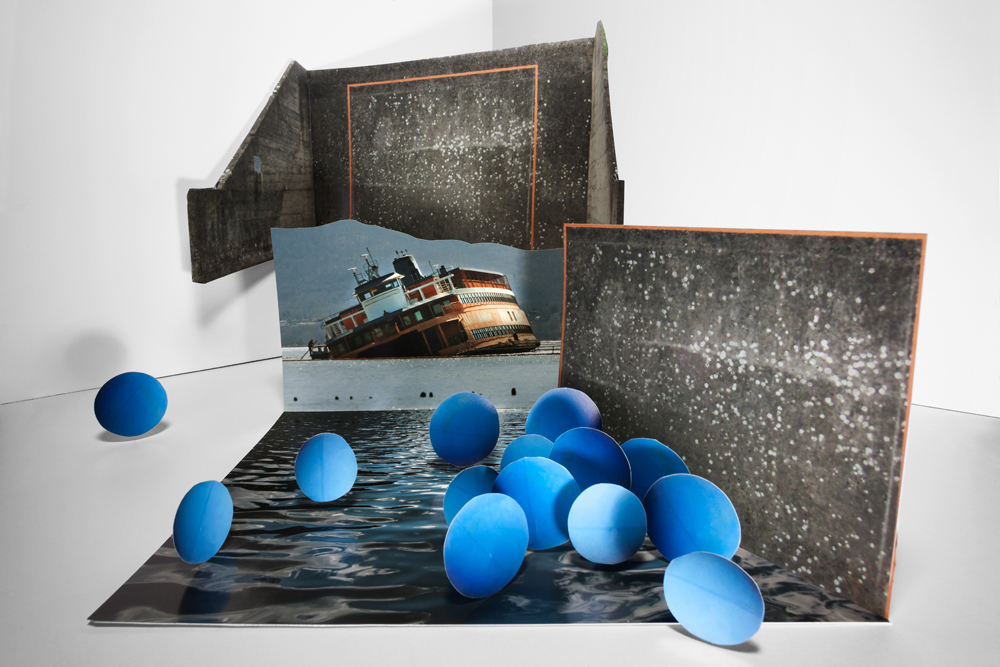

How We End. is a book of 41 illustrated short stories chronicling the romantic and sexual history of an unnamed and unreliable narrator. Each story details the moments in which the narrator realizes a relationship is over. The images are a visual representation of where that moment took place. They collage public imagery sourced from the Internet with private, intimate narratives to create scenes that are just as distorted and fragmented as the stories themselves. Break-ups are nothing if not one-sided or skewed. The book is about intimacy and heartbreak, but it is also about the way we communicate and the way truth deteriorates every time we tell a story. The relationship between the text and images is representative of the collaboration and friendship between writer and artist. There is an openness and a desire to communicate, but also a disconnect. Something is lost in translation, always.

Daniel was an accidental boyfriend. He pulled me behind the wall on the handball courts and told me that his parents were making him move to Staten Island. “I’m sorry,” I said. “It’ll be all right.” Aping behavior that I’d seen in movies, I wrapped my arms loosely around him and we stood like that, listening to the thump, thump, thump of blue handballs hitting the other side of the wall.

He called me that night and, when I asked why, he said, Because you’re my girlfriend now, right? I should’ve told him right then that he was mistaken. I couldn’t though, because I was convinced that it was my own fault for attempting to project an older, wiser version of myself. I felt as though I’d deceived him and, in the end, it felt kinder to tell him that “I was sorry, but I can’t date anyone from Staten Island.”

Mason would come over after school to do homework on Wednesdays, because no one else was home. We would kiss goodbye, but not much more than that. Mostly it was just the thrill of being alone together. I liked the way his shoes looked, next to mine, by the front door.

It was October and we were chasing my cat around the kitchen island. I don’t remember what it was exactly, but I remember laughing so hard that my throat was raw. We both had our socks on, running full speed in circles on the clean tiles. I slipped by the window and fell. I didn’t catch myself or break my fall. I landed hard, on my back. I didn’t cry because I couldn’t catch my breath at first. Mason came over and helped me up. We laughed about it, or I tried to, but I didn’t want to look at him. He didn’t seem to think twice about it, once he realized that I was all right, but my embarrassment was a thick, nauseating thing that I couldn’t get out of. I never wanted to see him again.

I ignored him for the next two days, which was all it took to shake him.

We were in front of elevators, which is a terrible place to talk about anything. I worried the whole time about the doors opening. The whole time was probably between three and five minutes, because that’s how long it took Hudson to say that he was sorry and that maybe we could try to be a couple again, later.

I let him say his part. I didn’t interrupt and I didn’t argue. When he was done, I handed him a gift that I’d originally planned on giving him for his birthday, two weeks from then.

“Whoa,” he said. “I’ve never gotten a breakup present before. That’s kinda cool.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I’m fucking awesome, huh?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Shit.”

Conor invited me to spend the weekend at his apartment, while his parents were out of town. He ordered a pizza, but I could barely eat. I couldn’t figure out what to do with my arms and legs. Every position I put myself in seemed completely absurd. I felt better after he kissed me, because he arranged me underneath him.

I needed to tell him that I was a virgin. I wasn’t trying to shut things down between us, but that was the message I sent. If I’d been able to talk to him about it at all, we could have gotten past it, but my throat just closed up.

The sight of Conor pulling his jeans up gutted me.

Pascal was still in high school, but he was French, which seemed to make him older. I lived with his family for a summer while studying at a nearby language institute. I tried not to stare at him during breakfast. For a week, I could barely lift my head.

I was friends with a woman who had been Miss Teen Nepal and loved drinking Long Island iced teas in basement dance clubs. Every night, walking home, I told Miss Teen Nepal that if Pascal was awake when I got home, I would kiss him. He was never awake.

Pascal and I went to museums together, but saw no art. Instead, we circled each other, miscommunicating about the time, lunch plans, which wing to visit next. The morning that I left, I woke him up, early. I had never been in his room before—terrified that his mother would catch me. He opened his door in boxers, half asleep and then walked back toward his bed. I went and sat with him, stared at a poster of a pop singer on his wall, felt self-conscious. There’s no nuance or subtlety to be had in a second language, spoken as poorly as I spoke it, so I kissed him and said no when he asked if he should write to me. He shrugged and went back to sleep.

Ray lived in the type of town that presidents retire to. I took a train in, over a holiday weekend. While I waited for him to pick me up in his parents’ car, I looked around the station with all its dark wood and parked luxury sedans. It wasn’t the type of place that I’d expected him to be from. At the house, his mother showed me where to put my things, in the guest bedroom. She was uncomfortable, but not unfriendly.

We went to the movies. His little sisters wanted to come but Ray said, No. During the movie, my eye started to itch. By the time we were back at the house, I had full-blown pink eye. His mom was sweet about it, but I could tell she was annoyed that I’d brought a disease into her home. If we could just stay together long enough, it would become one of those half- forgotten things you laugh about, but falling asleep that night, I knew that we’d never make it. I was destined to be known as that girlfriend with pink eye and it would never be funny.

I moved into my boyfriend’s studio apartment just as he was leaving for Europe. I spent a week pretending that he was watching me. I ate cereal in my underwear and read his most impressive books. I stood at the window and smoked a cigarette, conjuring his face. I drank wine and took long baths. I was trying to be the girlfriend he thought I was. By the end of the week I was exhausted and still had two weeks left, alone.

Patrick showed up the second week, with a ladder under his arm. The landlord had sent him to finish some wiring that hadn’t been completed before the move-in date. It was early in the afternoon. I was drinking a beer and wasn’t wearing a bra. Patrick noticed both things and smiled at me. There was nowhere in the apartment to go, so I sat at the dining table and watched Patrick work. I asked him questions about boats and offered him a beer, which he finished in four or five long drinks.

As he took panels off the outlets I could see tangles of wires, hidden from sight. There was more going on than I ever realized and Patrick told me that was always how it was. I got myself another beer while he finished working. Watching as he carefully returned each of the panels to the walls, I fantasized about having sex with him.

Before I could think of what to say or do, he was folding up his ladder and pocketing his screwdriver. He left and I kept drinking. From then on, it was Patrick I pictured when I imagined someone watching me.

Jack and I were friends. We were attracted. I wanted someone to say goodnight to and he wanted someone to go out to breakfast with. We were both hung up on other people and knew that we were standing in for them, but we didn’t mind. In some ways, it was the most equitable relationship that I’d known.

He had a photograph of his ex-girlfriend framed on his nightstand. She was standing on a beach, trying to prevent her hat from blowing away. I knew that Jack had been the one holding the camera. Seeing her next to his bed like that didn’t hurt me, but it did pierce something. The comfort of our bubble deflated slowly. I spent too much time wondering about where that beach was and who had bought the metal picture frame and which of them had put her inside it.

Despite never having wanted more from him, I began to feel neglected. My feelings for him weren’t deep, but I felt bitter that his were similarly shallow. We remained friends. Quickly, it was as though nothing had happened at all, because it barely had.

As a teenager, Tony and his friends would pick the locks to vacation homes and raid their liquor cabinets. He lost his virginity in one of those houses. As an adult, Tony was a locksmith. He didn’t understand how funny this was. I had thought we were just friends, but I found out that Tony deleted my phone number every Sunday and then had to ask someone for it again every Friday. He didn’t want his wife seeing my name in his phone. My roommates told me not to be a homewrecker. I said that it wasn’t homewrecking if they were getting divorced anyway.

The more my friends warned me off Tony, the more I wanted to be with him. The idea that I was enough to threaten someone’s marriage made me feel like a woman. The possibility of my name in someone’s phone having enough power to dismantle a relationship fascinated me.

Tony left his wife that spring. He started calling on Tuesdays, asking me to get drunk with him. I stopped answering.

Bennett and I were in a familiar place that had been transformed into something unfamiliar, for a party. It felt like a lucid dream.

With a shrug, he asked, “Have I mentioned that I might love you?”

“Fuck no, you didn’t mention that.”

That summer, I drove eight hours in an unreliable car to see him. We met outside the LL Bean in Freeport so that he could buy fly-fishing lures. I stopped short when I saw two moose skulls in a display case, facing each other. The plaque explained that the skulls had been discovered just like that—two bulls had starved to death after getting their antlers tangled.

When I looked up, I realized that I was alone. Bennett, who’d forgotten to mention that he loved me, had also forgotten that he was with me.

“At least I won’t starve to death,” I thought, and bought a cup of coffee.

I saw Milo around town for months before we ever spoke. All I knew was that he rode a motorcycle and went to the same bar I did. We made eyes at each other sometimes but, until the day he sat down next to me, I had felt like something between us was unbridgeable. I had imagined us speaking dozens of times. I had played out entire relationships in my head. In the fantasies, I was bold and willing.

The first time I heard him speak, his voice surprised me— quieter and more certain than I’d ever thought. He asked me if I’d ever been on a motorcycle. I shook my head no. He told me to go for a ride with him. You’ll like it, he said. It was as though he were reading the script that I’d written for us in my mind. He hit every line, just right, but when my turn came I stammered and missed my mark. My voice was so meek when I turned him down that I barely recognized it.

Owen had a job that brought him to California for the summer, where I was living. We were friends from college, but he’d grown up since then. He was working on a boat. His shoulders were broad. He made me laugh more deeply than anyone ever had.

During that summer, Owen admitted that he’d had a crush on me in college, which I’d known but enjoyed hearing. When I asked him why, he said my full name as though it held some power. I wondered what it was exactly that I represented to him. Whatever it was, it seemed to feel out of reach to him. I was still hoping that we might have some future, but he didn’t believe that I’d ever stick with him. He was probably right.

He watched me while I put on lotion and got dressed. He smiled. “Whatever you do, when it’s over, please don’t give me the whole ‘I just can’t do this anymore’ line.”

“Oh,” I said, putting my shirt on. “How about, ‘It’s over’?”

“Yeah,” he said, pulling me back. “But not yet.”

Purchase a copy of the book here.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026