Adam Katseff: The States Project: California

I first met Adam Katseff via Sasha Wolf in New York. It was September 2014. He was preparing for an upcoming show while I had my fingers crossed that one might be in my future as well. Adam’s conversational nature, good humor, and relentless commitment to image making were immediately recognizable. We dove into historical references and current topics within the medium, and I’ve since had the pleasure of witnessing his immense curiosity and persistent, evolutionary drive. In this series, Adam’s images are intrinsically tied to early photography made in California and the Western United States, yet a self-awareness and highly formal engagement make them undeniably current and relevant to photography at large. In a contemporary art market so often dominated by cold concepts, Adam has tremendous success making and selling work with which people want to spend their lives.

Adam Katseff was born in North Andover, Massachusetts and currently lives in Palo Alto, California. He received a BFA from Massachusetts College of Art, and an MFA from Stanford University. He was the recipient of the Murphy and Cadogan Contemporary Art Award, Anita Squires Fowler Award, and was recently the first recipient of the Sidney Zuber Photography Award. Katseff’s work has been shown internationally in recent exhibitions at the Phoenix Art Museum. Nevada Museum of Art, and The Hearst Galleries. His work can be found in numerous public and private collections including the Nelson Atkins Museum and the Nevada Museum of Art. He is represented by Sasha Wolf Gallery in New York City.

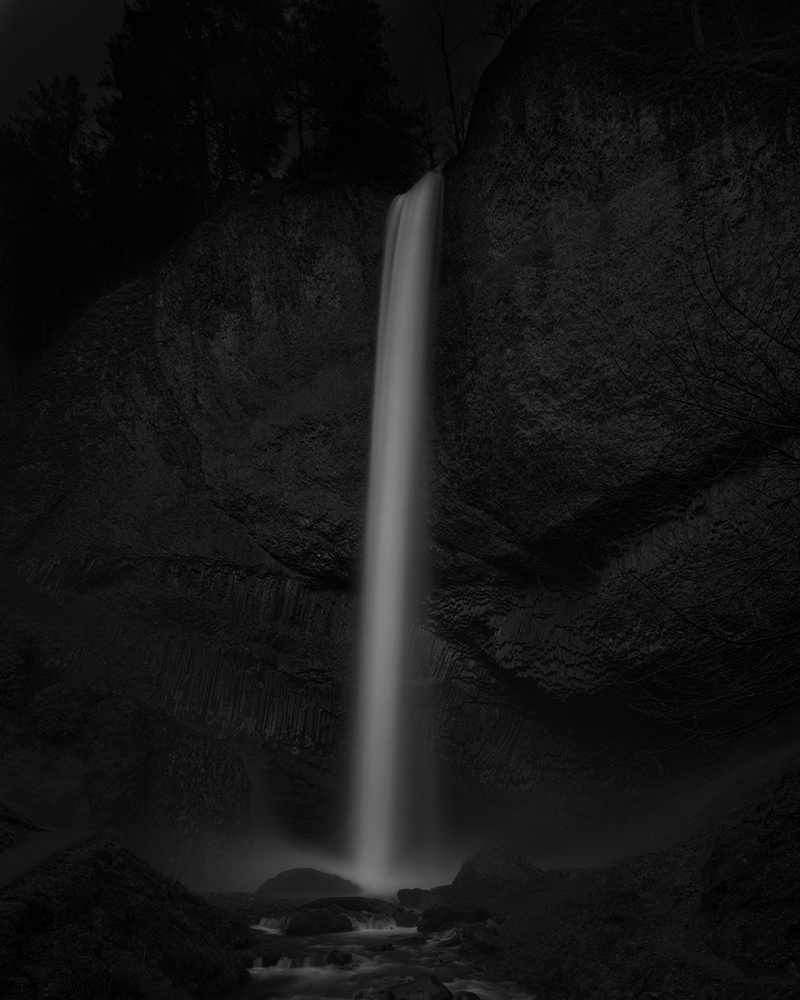

The subjects of my recent work are at the same time familiar and elusive. The outline of the image is easy to see one can quickly conjure the lake, the river, the waterfall standing out against the dark background but, as with memory, our imagination must supply the rest. This is the goal of my current series; to present the viewer with a partial landscape and invite them to compose the rest themselves. In this way the images become at once universal and deeply personal; an exploration of the line between physical space and our psychological relationship to it. Each viewer must invest their own experience, their own subconscious into the work to make it whole, and each comes away with an impression based partly in reality, and partly of their own creation. The scenes depicted in my work harken to the classics of the landscape genre, while at the same time using the methods and aesthetics of minimalist painting to distill their natural grandeur into simple essences. Through this series I hope to reinvent what it means to visually engage with the land, turning often photographed scenes into an exercise in nostalgia, perception, and a study in abstract elemental form.

Let’s start with some bio. You moved to California for graduate studies at Stanford and have stayed, now teaching at the University correct? What percentage of your photographic life has been spent on the west coast vs. east coast and, beyond the choice of subject matter, how did this relocation impact how you make pictures?

That’s right, I moved to California in 2010 for Stanford’s studio art MFA program, and I’ve been teaching there since I graduated – just enough to keep me grounded and inspired by fresh eyes. In terms of my identity as an artist, I’m just now realizing that we’re getting close to 50/50 in terms of time spent on each coast. It’s freaking me out! I still very much identify as an East Coaster, and think that this split sense of geography vs self has had a big influence on my work. Beyond just being a new place, I allowed myself to think of California, of grad school, of this new chapter of my life as a hard restart. It was a convenient and complete context shift that forced me to reconsider not just what I made work about, but who I was as an artist beyond my sense of self, my previous work, my sense of place and belonging in the world. I wanted to move on from the more personal, intimate pictures I had been making at home, where I had deep roots in both the land and the people.

This body of work has taken you to what appears to be breathtaking geography. Is this an ongoing project? What is your process like in the field? What percentage of your imaging process happens in the field verse back at home in your studio?

I do think of this work as an ongoing project. When I’m invested in a body of work I have a tendency to obsess. I hardly come up for air for months at a time, trying to figure out how to create this thing I’ve seen in my mind. How to solve this insane problem. Once I get past those initial creative and technical hurdles I can just relax and follow each body of work wherever it takes me. In that way I like to think I’ll keep adding to this and other series for the rest of my life – and of course as you mentioned, it’s a great excuse to seek out some pretty spectacular places.

My process in the field starts off with a lot of research on location. For this series in particular I was looking for very specific land features within reasonable hiking distance, since I was carrying around a very heavy camera, often times at night. I have such a short window of light to make these pictures that I usually spend the daylight hours scouting out the best one – or if I’m lucky two – vantage points. This process often takes multiple days, or even multiple trips. I’ve taken a number of flights simply to retake one photograph in this series.

I try to get as close to the final image as I can via the exposure itself. Sometimes I only have to make minor tweaks to get there, other times countless hours are sunk into post-producing an image into submission. The hardest part of post production for this series was taking images with a wide variety of exposures and lighting conditions and making them feel like a cohesive series of prints on the wall. There are a lot of challenges inherent to making very dark images, and I spent the better part of a year in a spray booth figuring out how to produce these photographs so they could be shown without glass.

Perhaps it’s the shared abstraction as a result of a very particular and/or obscure process that correlates these images with early western United States imagery of Timothy O’Sullivan and CA photographer Carleton Watkins. Can you speak a bit about the relationship between your work and these two photographers…what are the shared characteristics, and what do you feel is definitively different?

I think Carleton Watkins is the best landscape photographer to ever live. The clarity of his images gives them an emotional resonance that just hits me like lightening every time I see them. For me that respect is only amplified by visiting the actual sites that he’s photographed, as his images end up feeling like a more accurate depiction of the landscape than the landscape itself. When I got to the West Coast and found myself surrounded by this awe inspiring geography, it seemed futile to try and recreate what Watkins had already done perfectly. So in a way my landscapes serve as a counterpoint to this sort of sublime precision. I wanted to communicate a strong feeling of place through images which intentionally lacked information. There’s just enough definition in this series to trigger the memory, the imagination, but the rest of the image the viewer must supply themselves. Watkins captures a place with exquisite clarity, but my work forces a different perspective by virtue of being unclear.

You speak of your process as an exercise in nostalgia, perception, and a study in abstract elemental form. What role do you feel nostalgia plays in your pictures?

I use the word nostalgia as a reference to the memory of a place. Our spatial memories are often fragmented – certain things will come into very clear, almost photographic relief, while other aspects are left unremembered. Cameras have the ability to transcend memory in that way, to record a scene with immaculate, nearly unbiased detail and precision. Memory doesn’t work that way… at least not mine! I find that I have a tendency to form an almost graphic impression of a place, remembering shapes which suggest the whole but almost nothing else, filling the empty areas with my own invented content. I assume we all do this to some extent.

While working on the first round of landscapes that verged on total blackness I noticed that under the right conditions there would be a glimmer of light – something reflective (usually water or granite) that would make that aspect of the landscape look like a cutout from the rest of the nearly black scene. At first I avoided this sort of situation, looking for an almost total lack of variation in the light, but I then realized that perhaps there was something there – the stark contour of light on the landscape echoing the graphic cutouts of my own remembered places.

I really appreciate that! I’ve never really thought about it, but maybe that’s what photography can offer, a way to deeply explore some aspect of the world that we are curious about. For the last year or so I’ve been searching for new ways of visually exploring my perennial interest in structural form, and how our perception of something counteracts “reality.” While I think that theme has been more or less present in all of my series, this new work is different from the landscapes in almost every other way. I always seem to start a new project with a huge technical hurdle to try and overcome. In the case of the blackish landscapes, it was finding that the only way to get them right was to build a spray booth and acquire skills that only a professional car painter should have. At the moment I’m working in color, with a digital camera (for the first time), and in the studio with lots of lighting (also for the first time). I’ve been photographing these little “sculptures” I’ve been making… I don’t know yet what it will lead to, but my curiosity has definitely sent me on a windier (and bumpier) road than usual! I’ve been watching the documentary “Burden of Dreams” about the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. It makes me feel a lot better, at least in my case no one has died in the making of the pictures!

Within this great big world that is photography, you operate strictly as a fine-artists. Do you ever find yourself curious about assignments or commercial projects?

Always. I dream of them actually. Working as my own boss almost 100% of the time can take its toll. Not just on the “business” side of things, but even artistically speaking I’m always 100% in charge of what I’m doing. I’m sure I’m idealizing the world of assignments and commercial projects, but sometimes it sounds so nice to be given a task, and my job is just to execute it well. Solving other people’s problems sounds very appealing to me right now, rather than creating my own arbitrary problems and working my ass of to try to solve them. There’s something a little incestuous about it – this complete artistic navel-gazing. I’m sure in reality there are downsides to assignments and commercial work and I’d go crazy being told what to do all the time, but it’s comforting to romanticise it! I definitely feel really lucky to be able to make my living as an artist and get to play by my own rules most of the time. Perhaps I’ll just have to see if the grass is actually greener on the other side… are you hiring, McNair?

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 14th, 2016

-

Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 13th, 2016

-

Adam Katseff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 12th, 2016

-

Nigel Poor: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 11th, 2016

-

Carlos Chavarria: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 10th, 2016