Nigel Poor: The States Project: California

Nigel Poor explores the world from an incisive, yet graceful perspective. We once met for a cup of coffee where she found a worn-down pencil, something I would likely have swept to the curb, but for her became the investigative launch point for a new project. Washing and imaging books once deemed dirty demonstrates how she uses photography to communicate her unique vision. Over the past five years, Nigel’s photographic practice has shifted from the creation of new imagery to exploring the world through previously created works within San Quentin prison. Her multi-staged project shared here teaches us how photography and visual literacy can reveal cultural subtleties often overlooked or purposefully ignored.

Nigel Poor lives and works in the Bay Area. Her work has been shown at many institutions including The San Jose Museum of Art; Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose; Friends of Photography; SF Camerawork; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and the Haines Gallery in San Francisco. Her work can be found in many collections including the SFMOMA, the M.H. deYoung Museum, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. She received her BA from Bennington College and her MFA from Massachusetts College of Art.

For many years, Nigel’s work has explored the various ways people make a mark and leave behind evidence of their existence. She is interested in forms of portraiture and explores this vastly mined photographic area through unconventional means, using fingerprints and hands, objects people have thrown out, human hair, dirt, dryer lint, and dead insects as indexical markers of human presence and experience. Her work explores the troubling question of how to document life and what is worthy of preservation.

In 2011, Nigel’s interest in investigating the marks people leave behind led her to San Quentin State Prison where she taught history of photography classes for the Prison University Project. This experience changed the focus of her practice and the visual presentation of her ideas. She has since moved away from being a solely visual artist working alone in the studio and now spends the majority of her “studio” time inside the prison working with a group of mostly lifers on photographic projects and producing radio stories about life inside. She is a Co-Founder and Co-Managing Producer of the San Quentin Prison Report Radio Project (SQPR). In 2014, SQPR was presented with an Award of Excellence from the Society for Professional Journalism for “highlighting the stories of a prison community that outsiders rarely hear, including stories not only told from within the prison, but also produced by inmates.” And in 2015, Nigel was the recipient of A Blade of Grass Fellowship for her work with the SQPR radio project. Along with Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, two incarcerated men at San Quentin Prison, she is the co-producer and co-host of the new podcast Ear Hustle, which is one of the finalists for the 2016 Radiotopia podquest.

Nigel Poor is a Professor of Photography at California State University, Sacramento.

In 2011 I started volunteering at San Quentin State Prison teaching a history of photography class through the Prison University Project. That experience led to other projects including working with a group of men to produce audio stories about life inside (air on KALW, 91.7 FM on the show Crosscurrents) and collaborating on a photographic project, which has three distinct parts.

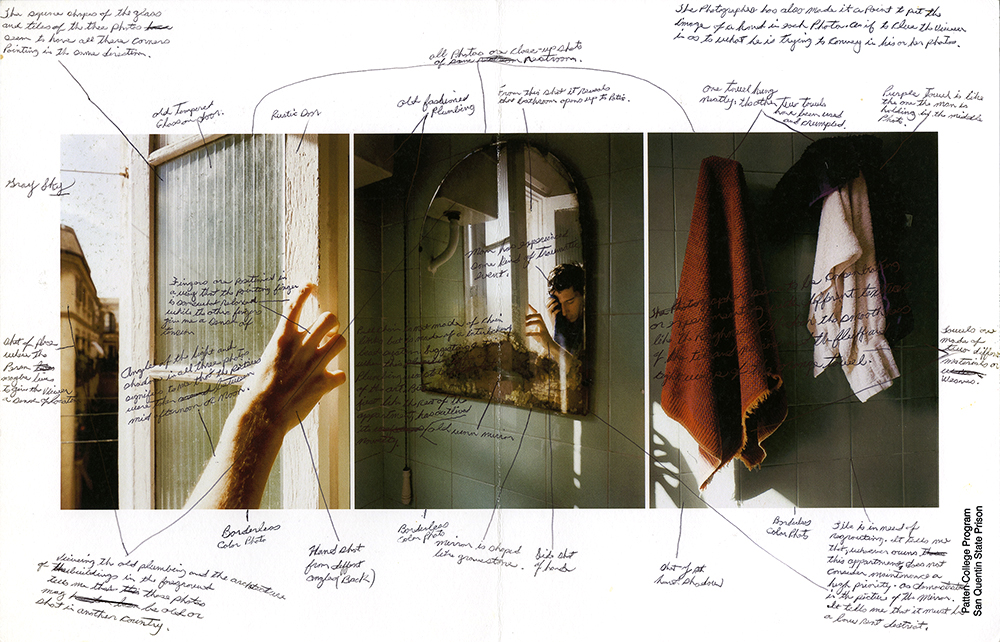

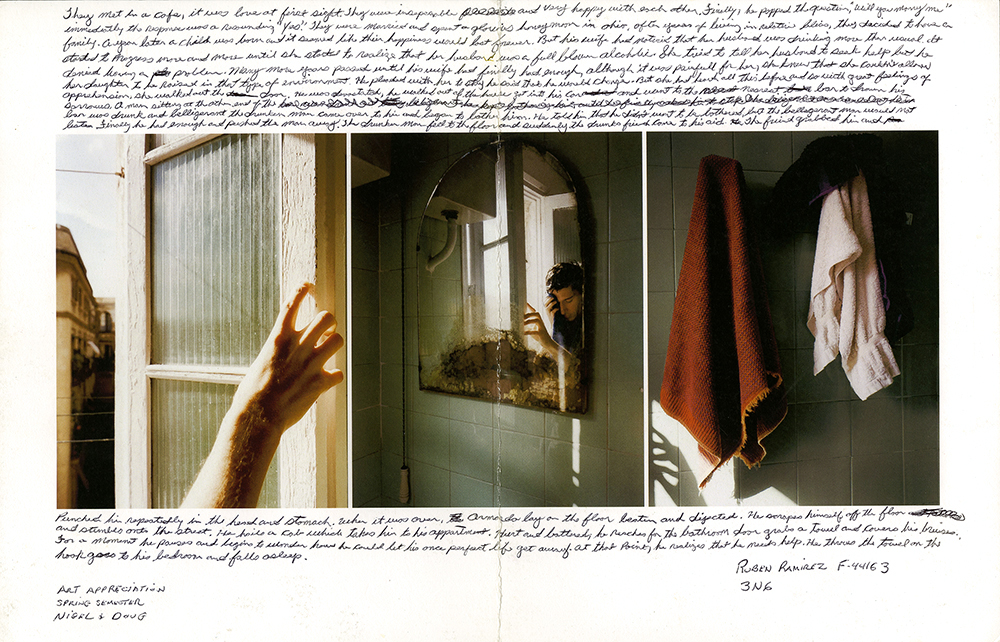

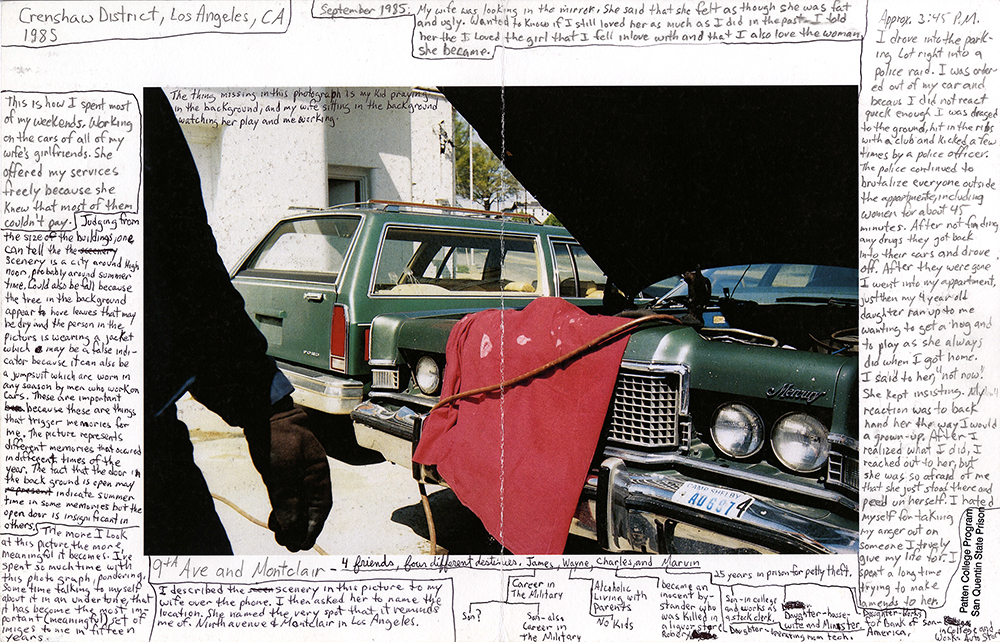

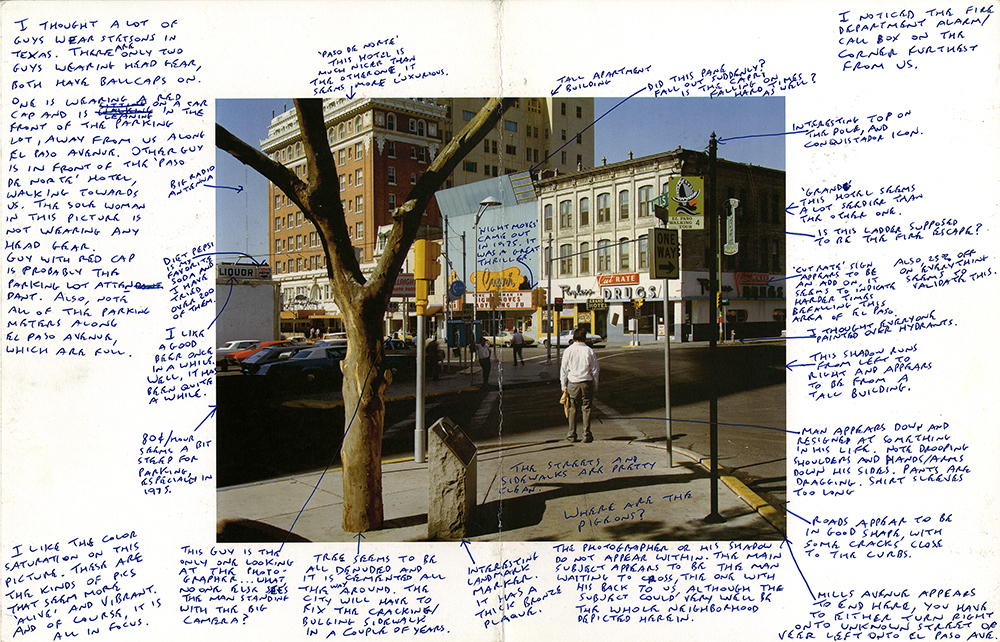

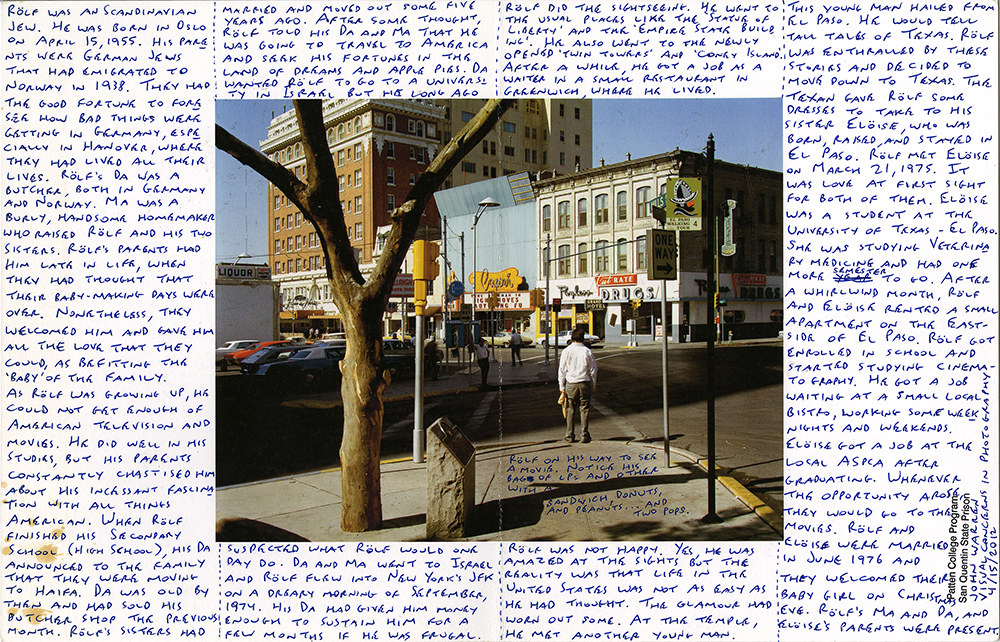

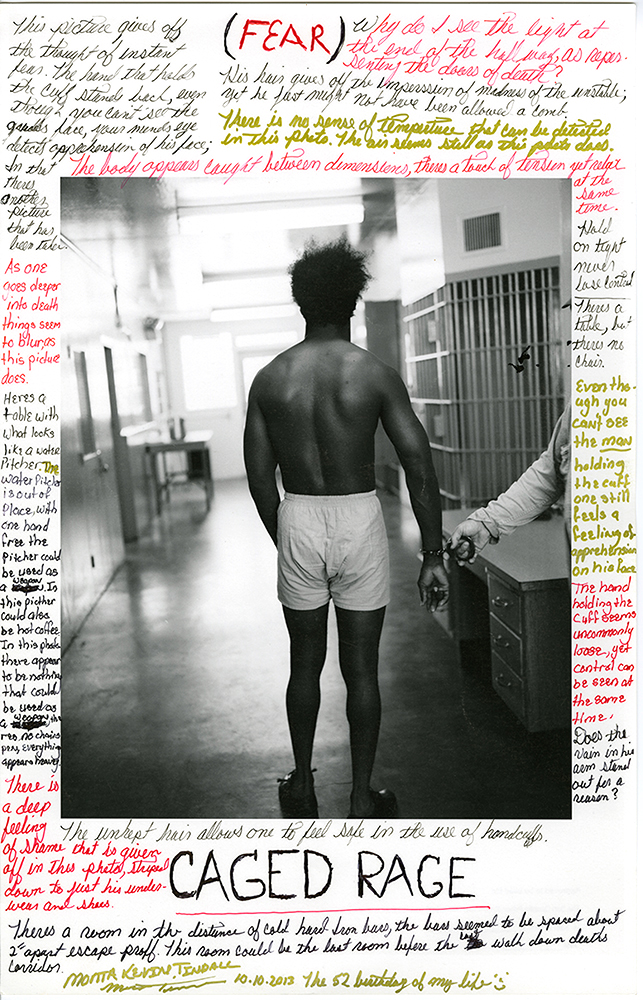

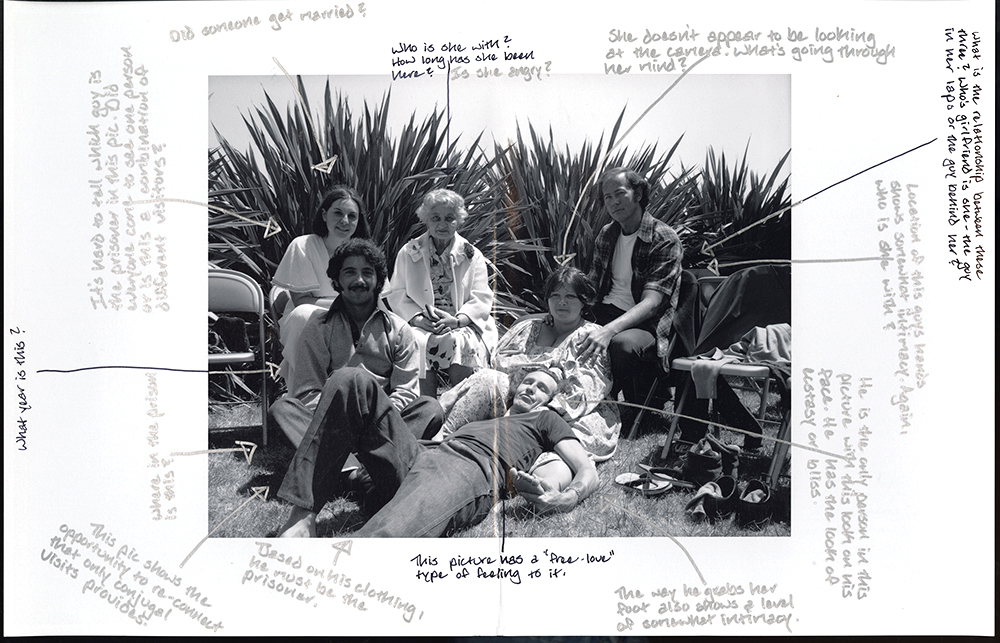

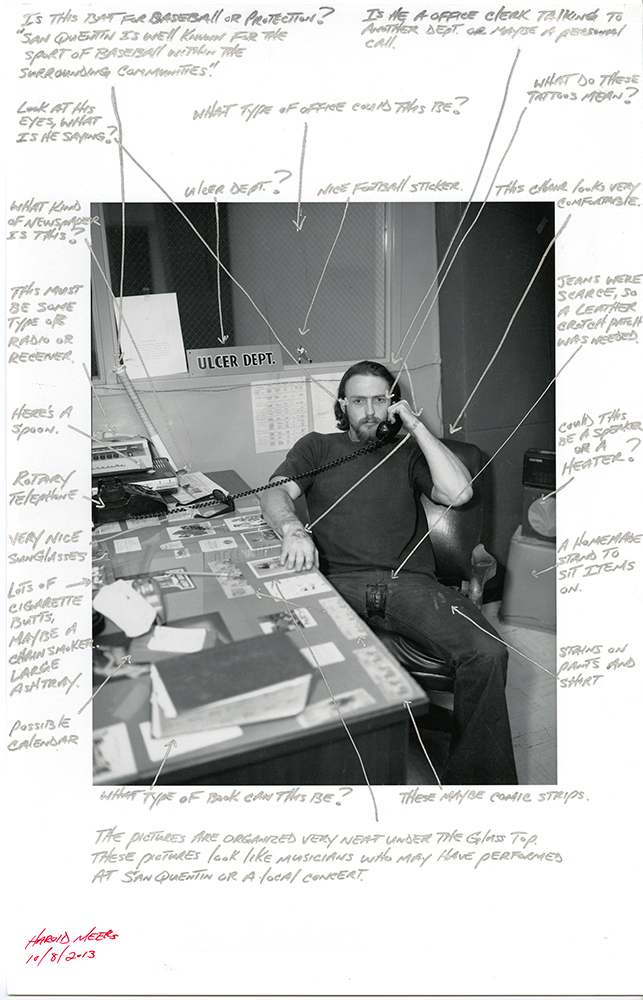

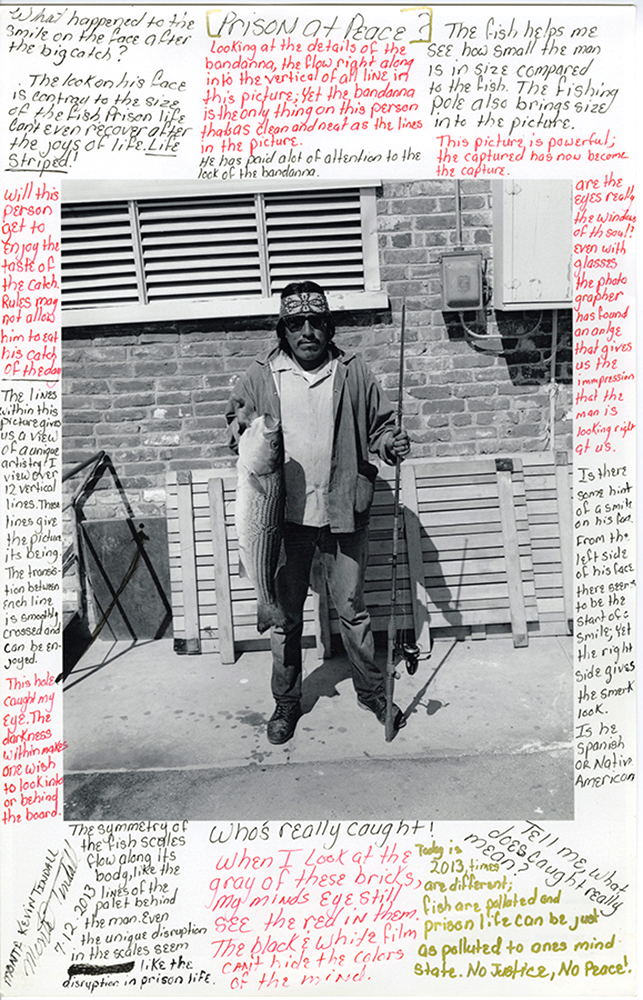

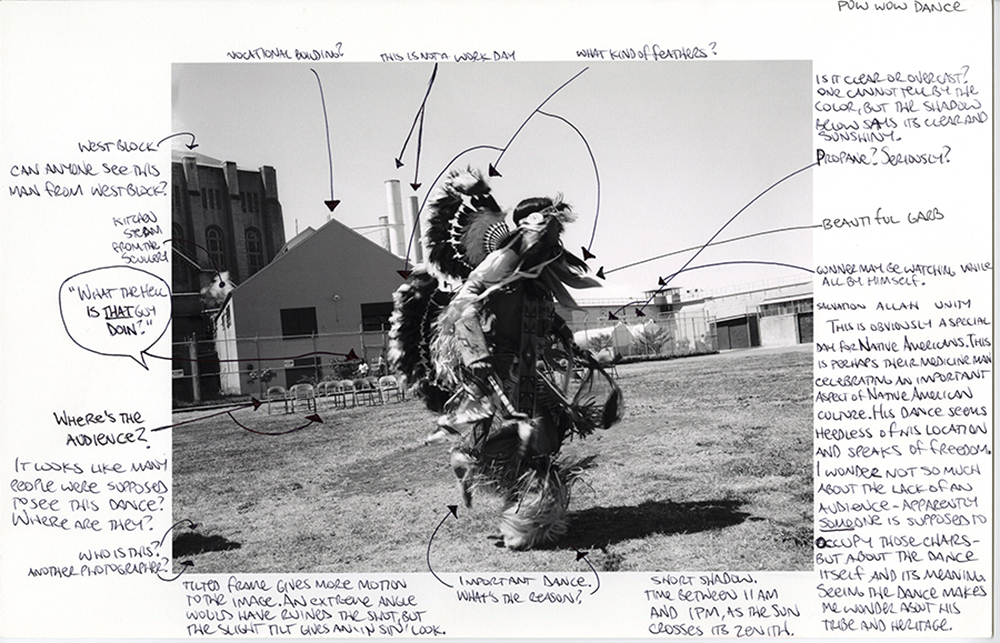

Part # 1 Mapping Artists Images

Two sided 11×17” inkjet prints with handwritten text

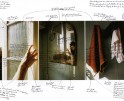

Part # 1 started as an assignment given to the men in the history of photography class I taught with Doug Dertinger at the Prison University Project. The men are not allowed to use cameras but we wanted them to get a sense of creating and interacting with images. Each student was given a 17×11 inch image by a different artist. The image was printed on both sides of the paper with enough of a margin around the image for handwriting. The men were asked to physically interact with the image on the page. They used one side to map the photograph/image through words and drawings, dissecting what they saw in order to assemble meaning and construct a possible narrative. Once that was done they used what they discovered to write a response to the image on the second side. Their response could be a formal reaction to the image or verge into creative writing: using the subject and setting of the image to produce fiction or facilitate personal memoir. The men live with the image for almost a month so the paper itself took on shape and character. By the end of the assignment they had produced an object that was the evidence of their interaction with the image, a piece that was not only a conversation with the original image but in some ways a new and unique image itself.

The examples of the image mapping exemplify the distinctive way each man interacted with the photographs. Through their markings and use of language and drawing, a singular voice emerges that not only connects with the style of the image but also divulges something about how the individual sees the greater world through the photograph.

Educated at Bennington College and Massachusetts College of Art, you’re originally from the East Coast. What brought you to California, and how has your time in this state influenced how you have developed as an image maker?

I finished graduate school at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston in May of 1992. That summer I came out to San Francisco to visit my sister. I didn’t know the city at all but was fascinated by it. I knew I wanted to make a big change so I went back to Boston, got my things in order, packed up a U-Haul, drove across the country and by November I was living in SF without a real plan. I am a New Englander and in some ways being in California threw me- I missed the seasons, the light, the sensibility – that felt integral to who I was. I am not sure California influenced me as an image maker but having to situate myself in a different place caused me to examine my assumptions about who I was, what interested me and I found it didn’t matter all that much where I lived because my work is about examining the everyday and cool, weird, touching, frustrating, beguiling, confounding shit that happens no matter where you are.

I will say this: growing up the writers that meant a lot to me and helped to shape the way I like to be in the world: Raymond Carver, Flannery O’Connor, Robertson Davies, Nathaniel Hawthorne to name a few, didn’t seem to feel like California and I also missed attics & cellars and older New England architecture and empty old buildings that were fun to explore and looking in people’s windows when I took evening walks- the spy in me, the person who likes to quietly observe others unseen- for some reason that didn’t seem as possible in California – so I just thought about those things more and maybe some of that way of thinking came out in the work I was doing. I felt a little like an outsider here and that is a good place to be when you want to observe.

From forms of portraiture and unconventional subject and means such as using fingerprints, objects people have thrown out, human hair, dirt, dryer lint and dead insects, your work has long explored what you term the “troubling question of how to document life and what is worthy of preservation.” What exactly do you consider to be the troubling issues of documentation and subject identification? How has this influenced your decision work with San Quentin Prison inmates?

The trouble question has to do with understanding what we value and what has significance. I am most interested in the small things people do and the evidence they leave behind of their struggle to find meaning. I wonder about and ruminate often on trying to grasp what meaning there is in life. I am aware we are constantly in a state of recognizing what was once known as now- and that is a tough position and to me the crux of being human. I want to use to my best advantage the knowledge that most things we do are comic, tragic and rather tender as we trundle toward the inevitable.

I don’t grasp what is knowable- fact & fiction swirl around each other so beautifully and often I am not sure which I am looking at. But I like that state of being – that inability to concretely say what or who someone is gives me hope that we are always in a state of becoming. It allows us so much flexibility. I like to be in new situations, in places I don’t completely understand that will push my assumptions and perceptions. I will admit I was very curious to go into a prison but I knew I couldn’t just go in to assuage some curiosity I had. So starting there as a teacher was very important – it gave me a year and half to get to know a bit and to be seen by those who live inside. Teaching a history of photography gave me a way to connect with the men through conversation about photography. Photography allows us to ask questions and connect with people we may at first blush feel like we have nothing in common with – and that is amazing.

This idea of the troubling question is even more troubling now as I try to negotiate the prison system and the complicated power dynamics of inside & outside people working together.

You’ve shared four stages or portions of your project at San Quentin: Mapping Artist Images, Mapping Archive Images, Archive Typography, and the San Quentin Prison Report which is a radio program highlighting the stories of a prison community that outsiders rarely hear, including stories not only told from within the prison but also produced by inmates. Do your feel there is a progression toward a particular culmination? If so, what might that be?

Well we are progressing toward a new and exciting audio project- called Ear Hustle which is going to concentrate on storytelling that will incorporate more elaborate and creative sound design. It is not a news or journalism project, it is storytelling and it is really what I have wanted to be doing inside the prison. Things in prison take along time- you have to spend time getting the lay of the land, observing and trying to understand the complex relationships of prison politics. There is so much no one can really tell you- so being observant and being comfortable with having your assumptions challenged is paramount. It took a while to get there but it seems to be coming together. We are finalists for the Radiptopia podquest https://www.radiotopia.fm/podquest/ .

I want to find a way to make the SQ Archive project reflect that confusion I mentioned earlier about fact & fiction each recalling the other and I think somehow this podcast will help me figure out how to bring the archive project to fruition.

You began with Mapping Artist Images. What was your initial goal with this process? Was there a particularly powerful moment you can share of your realization that an inmate’s marking and language used to described a photograph not only reveals their relationship to that image but divulges something about how they interpret the greater world through that image?

Mapping Artists images began as an assignment in the history of photography class I was teaching inside with my colleague Doug Dertinger. We wanted the men to have the experience of “making” and since they cannot use cameras we had to come up with an alternative. At one point in the class we were looking at work done by photographers who had gone into prison and a student said “they should give the monkeys cameras”- meaning the men should have the opportunity to speak for themselves and not be interpreted through other people’s vision. That made a lot of sense to me. So giving the men photographs to dissect, and write on was a way to give them the opportunity to tell their own stories- stories that were inspired by the photograph, how they interpreted it and their experience. We never asked them to write about prison but many of the men did. The most powerful example of that was the piece Michael Nelson did in solitary confinement about the Misrach & Sugimoto photographs. I am attaching a PDF of his essay that shows very clearly how this writing about how ” images divulges something about how they interpret the greater world through that image”

In your Archive Mapping project you describe the photographs you are using as “direct, blatant images that rely on the assumption that photography speaks the truth, that it has an unquestionable veracity.” What visual properties inform this interpretation? To what extent do feel documentary photography’s identity does or doesn’t still rely on this assumption?

I said that about the images because I “know” these photographs were taken as evidence to document events inside the prison. But you see just by saying that I am making assumptions- it is a reasonable assumption because these were taken by correctional officers and used in official reports- but I have no way of knowing how these photographers felt making the images. Maybe some of them had artistic intentions, or may be some of them hoped their work would be used as evidence for the need of prison reform or maybe they saw the men as animals or specimens to be coldly observed and documented. The not knowing exactly fascinated me. I don’t fully trust the idea of documentary photography- no one operates in the world with such passivity to be able to neutrally take in experience. Everything is filtered through multiple layers. Sure I think photographs can start to hint at truths but I am not sure about how solid that truth is.

When I look at the images in the archive I sometimes see an attempt to show facts without emotions- a photograph of a hand with fingers that have clearly just been severed in a machine, a man bleeding out on the floor, a person with self inflicted wounds holding up his shirt with slice marks on it- one cannot help but think the photographer was only thinking about the document, not about how this person felt or what they were experiencing. And sometimes the images are blatantly dumb like a close up of a clearly broken window with a finger pointing out it- the negative is titled “broken window”. It couldn’t be any more apparent what is happening. But then there are the unexplainable ones…. the most interesting ones.

You speak specifically of ineffability as a “state of not knowing that we are ultimately given the opportunity to engage in the most difficult of life’s questions.” What is it about things too great or extreme to be expressed in words that facilitate difficult questions? How does this manifest visually in your Archive Typography?

I am repeating myself but I feel most engaged in pursuits when I am not sure of what is happening, I don’t mean that I like chaos but I like to puzzle things out and photographs that are open ended allow me, and I hope the viewer, to move around below the surface to the murky area where things are a bit untethered and maybe even scary. It is where the subconscious is, the place where we can try to answer what it means to be human and try to find meaning. It requires sitting with something for a while and feeling confused – it requires pondering and that expands the brain and one’s thought process. Things that are answered too quickly don’t require much of us, they don’t ask us to look at the things that frighten us like: loss, death, the chance of our birth and our circumstance, why people suffer, why is there evil, they also don’t require us to praise joy and great beauty and the fleetingness of being in the moment.

There are images in the archive that are so strange like the one I attached of the man standing almost naked with a washcloth over his head- what could be happening here? There is no title beyond “Dr. Barry”. We know we are looking another human being but the circumstances are not recognizable in anyway. Or the image of a hand holding up a regular size band aide- why? In the scheme of violent images where men have gushing wounds or have been violently beaten why photograph this tiny everyday band aide? I find myself lingering the longest on these images because I want to understand the why and how of it- and because I am a photographer I try to understand what this person behind the camera was thinking and feeling- did the photographer care about connecting with the humanity in front of the lens?? Did they care about the story?

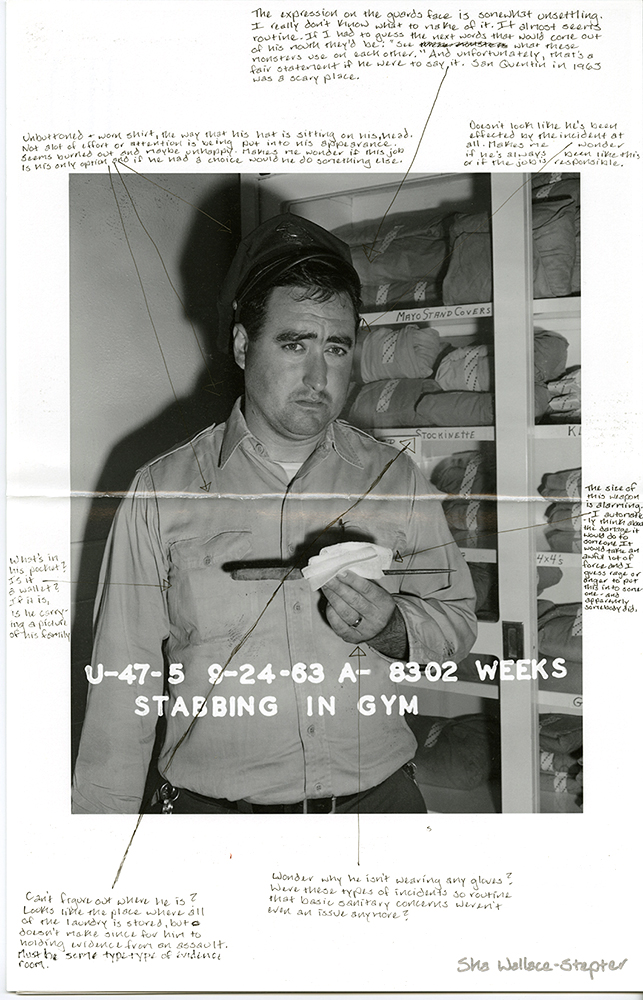

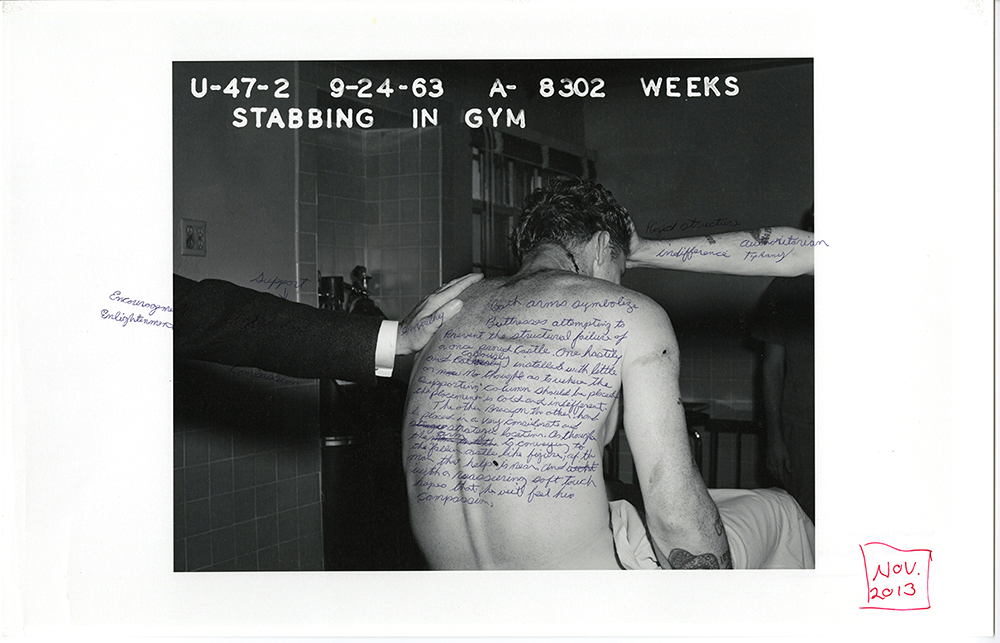

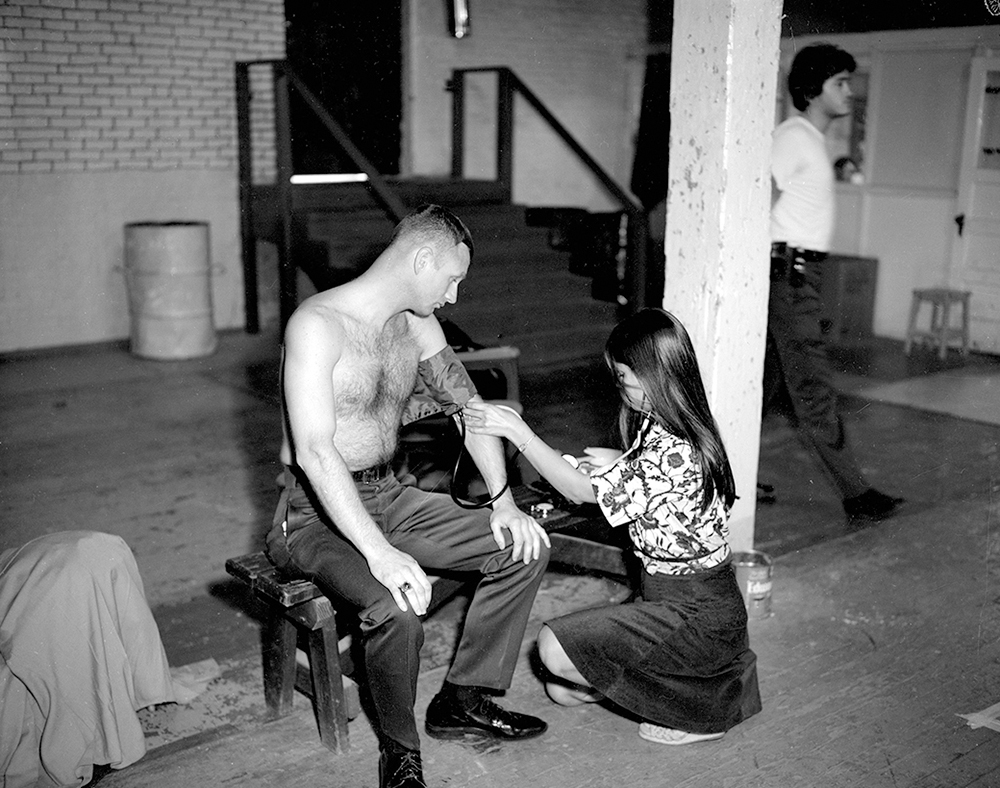

Part # 2 Mapping Archive Images

11×17” inkjet prints with text

In 2012 I gained access to an unexplored archive of historic negatives taken at and housed inside San Quentin. I am curating this uncharted archive (which is comprised of 1,000’s of 4×5 negatives), selecting negatives to print and collaborating with a group of men at the prison to create a new body of work that explores how images can be viewed and interpreted through unique and specific experience.

Many of the images are quite difficult, they were not taken with an artist’s eye or with the intention of creating a visual experience that is generous or transformative. These images were taken by correctional officers whose job was in part, to provide visual proof that an event took place. They are direct, blatant images that rely on the assumption that photography speaks the truth, that it has an unquestionable veracity.

As I did with the photographs brought to class, the images from the archive are used as canvases for the men to interact with. Each image is treated, in a sense, like a crime scene to be studied, written on and mapped in order to reveal its undisclosed story. The negatives were originally taken to document specific places and events. They were not meant to evoke emotions but through our intervention they become objects that inspire, house memory, personal experience and create a visual dialogue with a mostly invisible population.

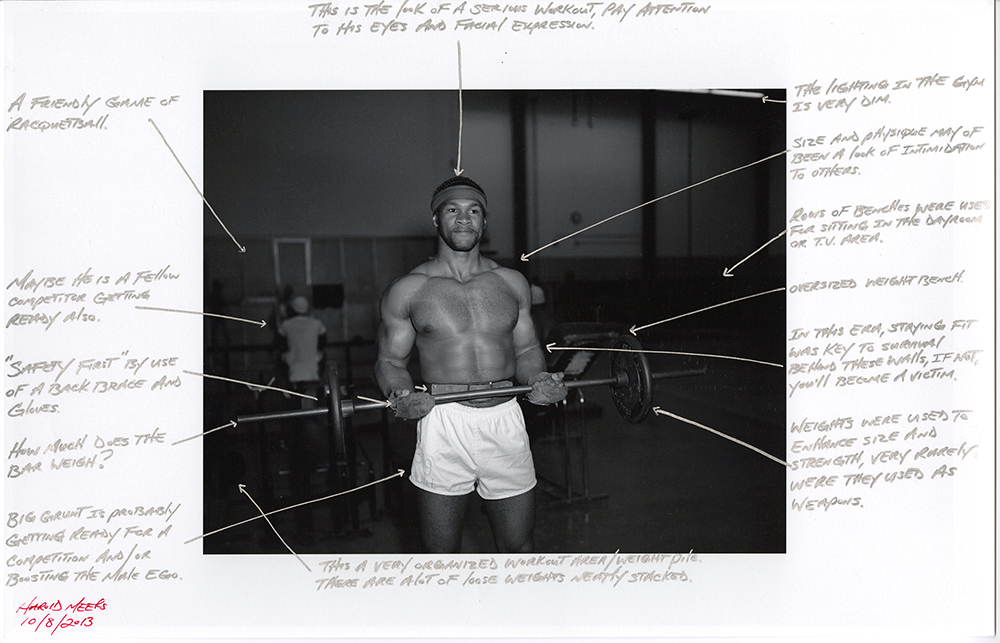

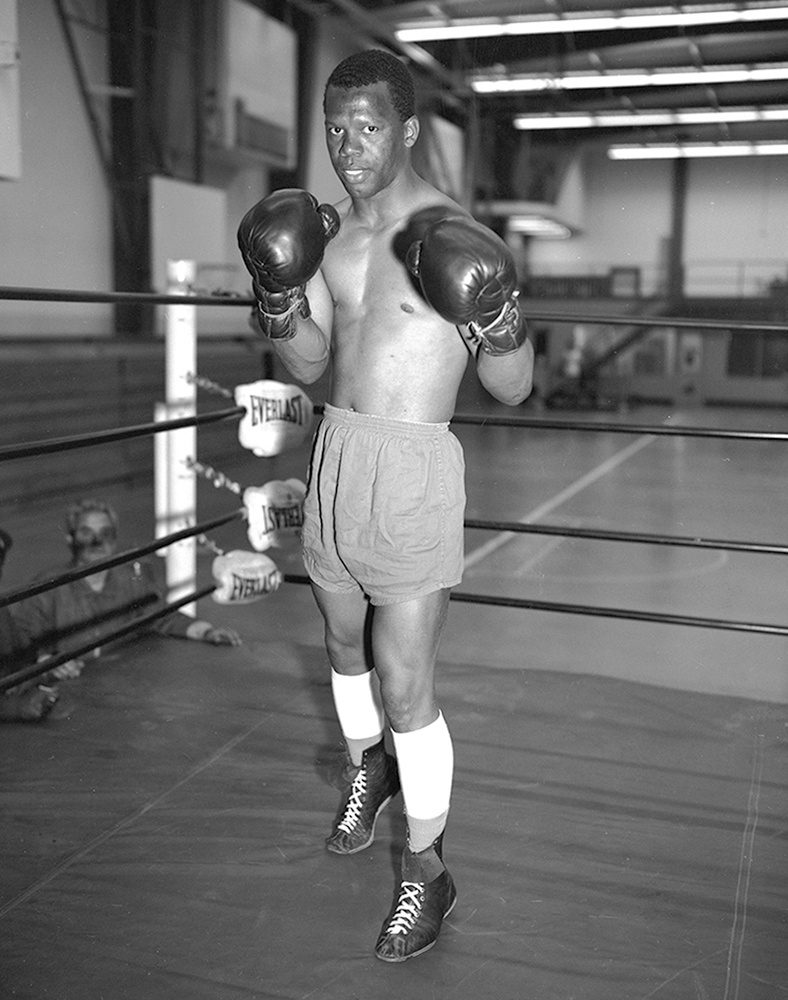

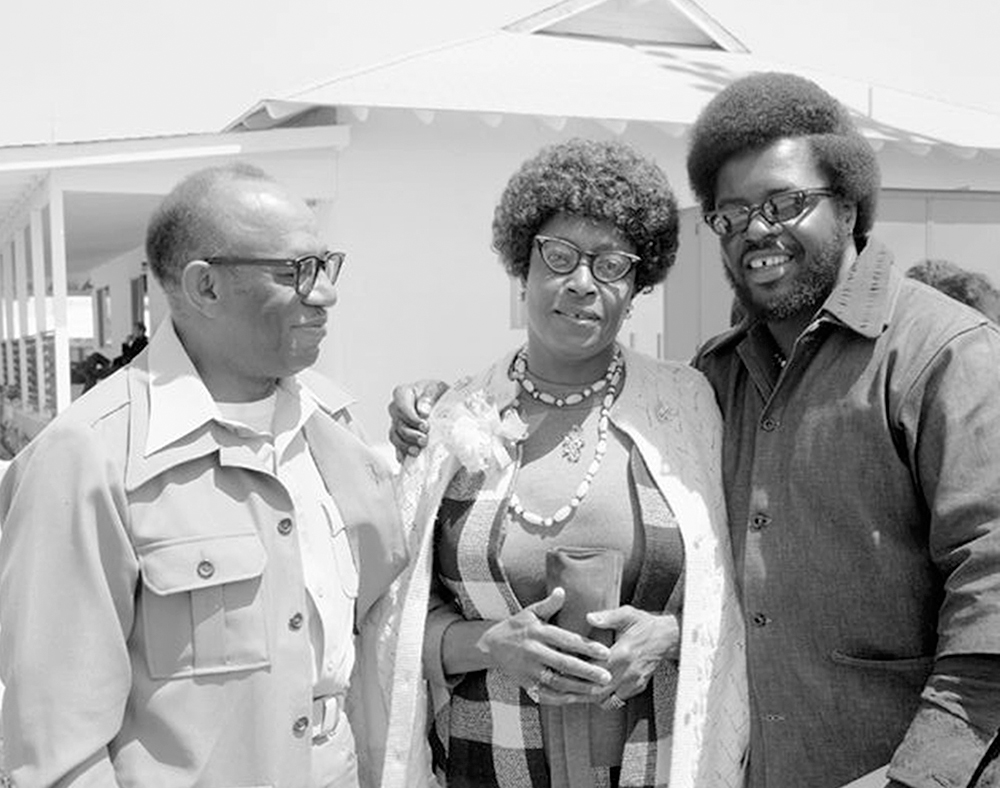

Part # 3 Archive Images

Each typology is comprised of nine 10×8” images and one 20×16” inkjet print

The archive itself is an exhaustive document of prison life. The 1,000’s of 4×5” negatives were taken between 1960-1987 and as previously noted, they were taken as a way to document events, they had official purpose and were not meant to be interpretive or creative. But, of course every photograph taken has a point of view and the photographer, whether he or she is conscious of it or not, creates meaning in an image simply by the power of placing a frame around the world. A correctional officer photographing a murder, suicide, escape attempt or prison wedding is no different.

The time that I have spent working inside a prison has only deepened my questions about human nature and how we relate to others. The more time I spend there the more complex and engaging these questions become. Assumptions are continuously challenged and the world inside and out becomes more complex. While working with the men mapping images by other artists and writing about the archive images is important and essential work it is also imperative to deal with the archive itself, to study the images and hope that answers will be revealed. I am looking at them as an outsider and although the amount of time I spend in prison affords me a bit of insight I am not an inmate, I have never committed a violent crime, I don’t know what it feels like to be confined or to have terrible remorse over hurting another person. I also don’t know what it is like to be a correctional officer and be tasked with keeping a prison running safely. I know photographs don’t tell complete truths, I know they are unreliable witnesses but by curating and studying this archive I hope to be able to at least put together a visual experience that talks about the wanting to know, the possibility of knowing and the acceptance of always leaving room for the not knowing.

To that end I have put together groupings of images that fall under twelve categories.

- Escape & Confinement

- Correctional Officers, Inmates & Volunteers

- Holidays & Ceremonies

- Education, Food & Health

- Murders & Suicides

- Violence & Investigations

- Work & Leisure

- Injury & repair

- Family & visits

- Blood & Evidence

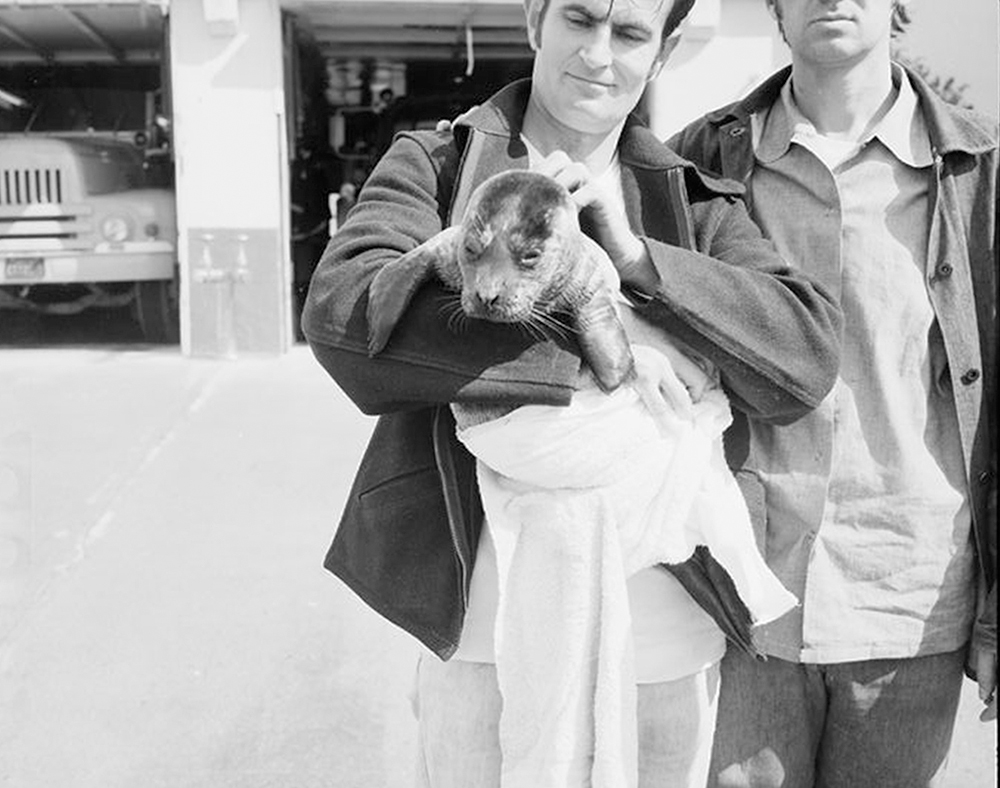

- Animals & people

- The Ineffable

Some of these categories are specific to prison life but others reflect experiences all of us have. Every life, whether free or incarcerated must consider family, work, health etc. So it is through these categories that we can connect and recognize each other. Prison can be violent; a place without hope where power struggles are constant and complex and this category must also be addressed. And finally there is the ineffable, perhaps the most interesting, the category, which does not attempt to answer any questions, the category where we must be satisfied to not know. Again every life whether free or incarcerated lives with the ineffable – it may be in this state of not knowing that we are ultimately given the opportunity to engage in the most difficult of life’s questions.

While the San Quentin Prison Report is surely about life in prison it is also a project about the possibility of transformation and the belief that the photographic image still has the power to challenge assumptions and provide an opportunity for conversation. Photography is ultimately what got me access to prison, talking about images with the men inside is what has created our bond and strengthened our dedication to work together and we hope the work produced by The San Quentin Prison Report will get others interested in contributing to the conversation.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 14th, 2016

-

Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 13th, 2016

-

Adam Katseff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 12th, 2016

-

Nigel Poor: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 11th, 2016

-

Carlos Chavarria: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 10th, 2016