Edward Bateman: The States Project: Utah

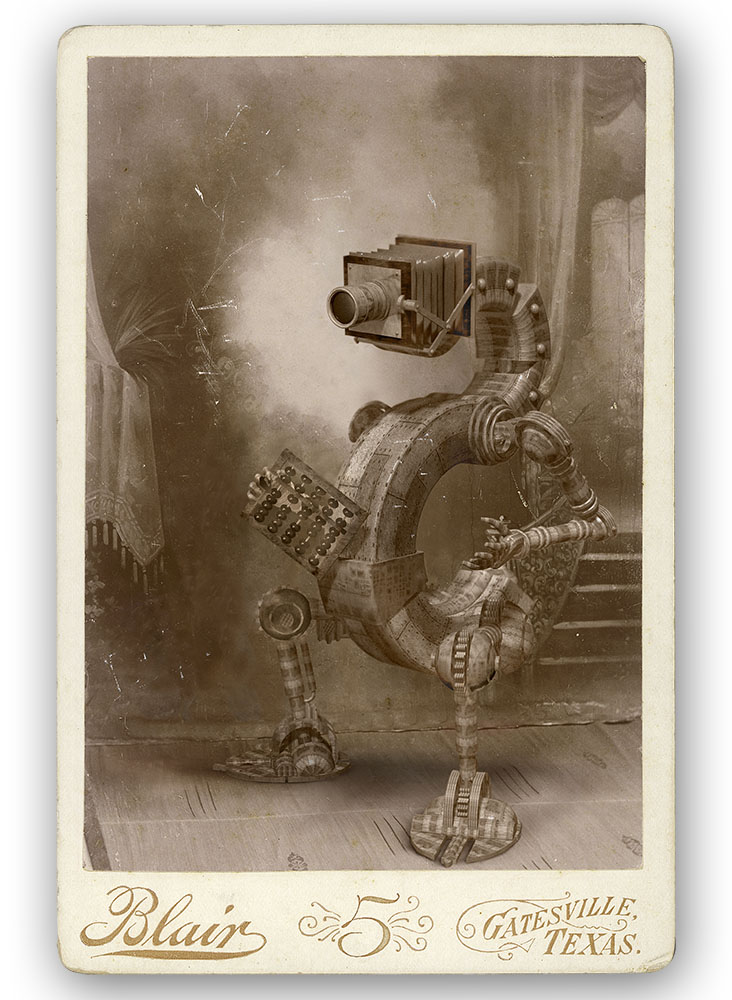

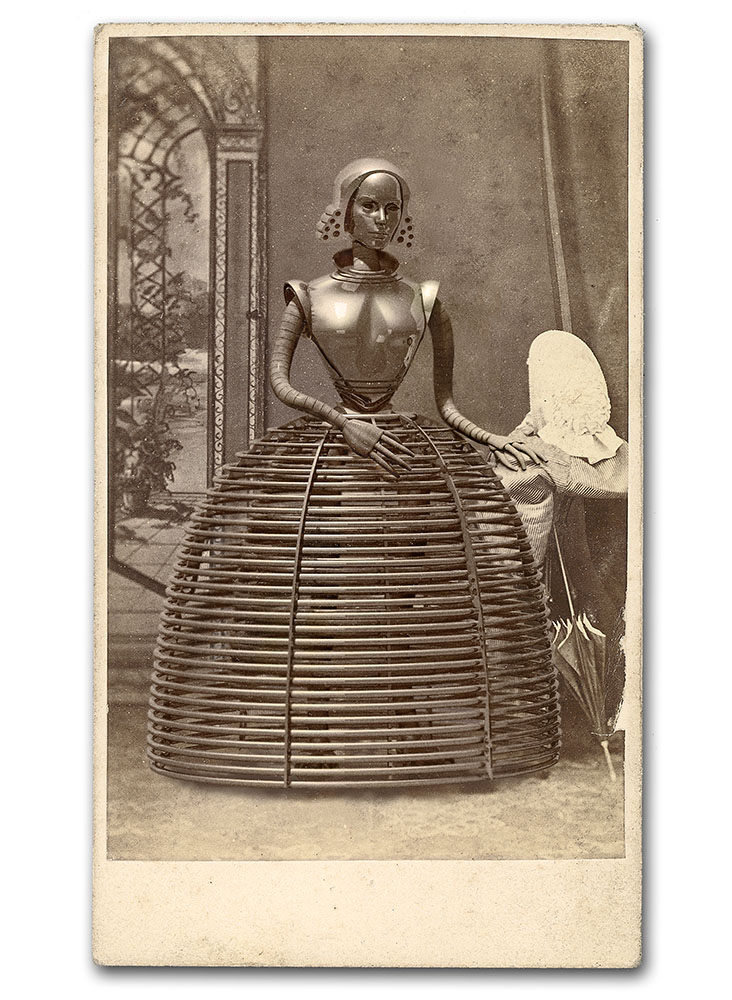

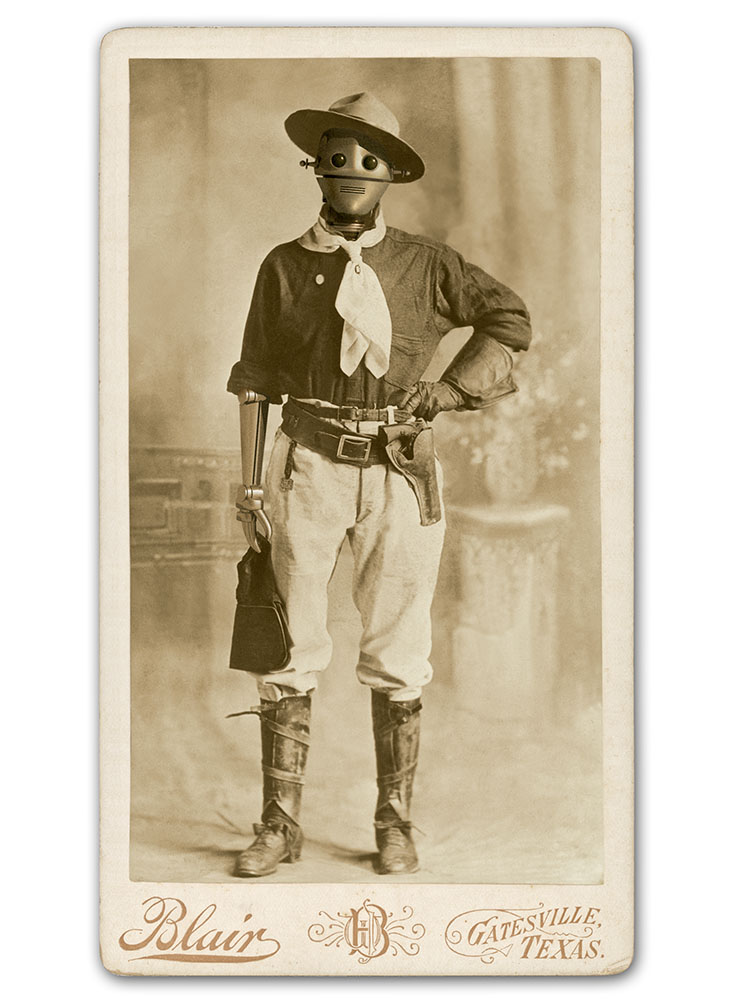

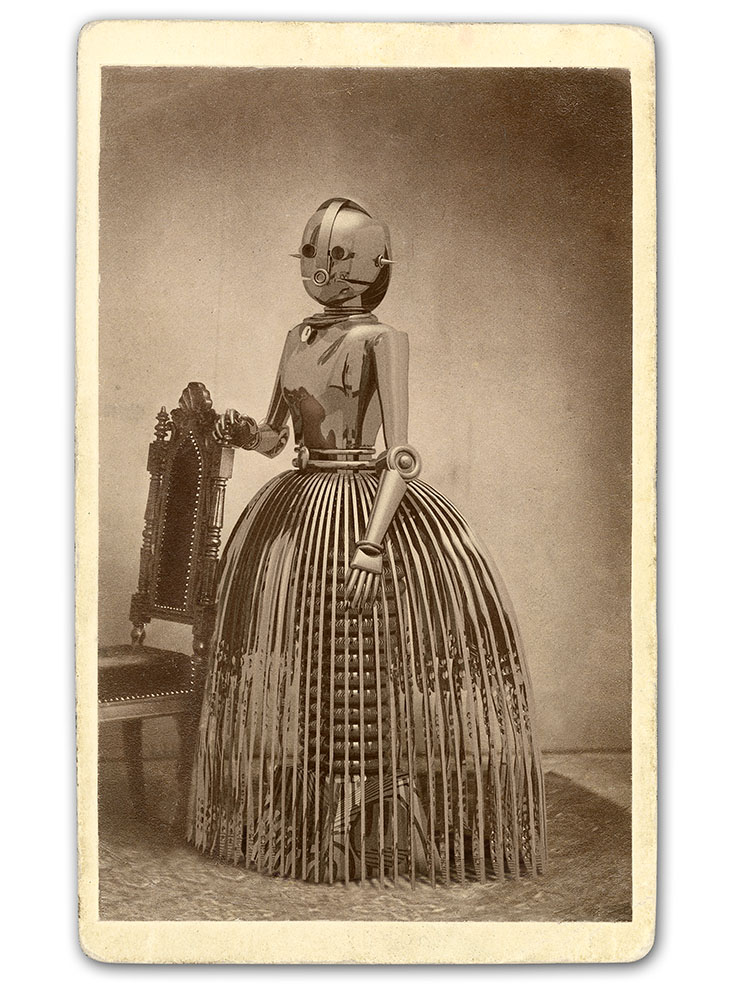

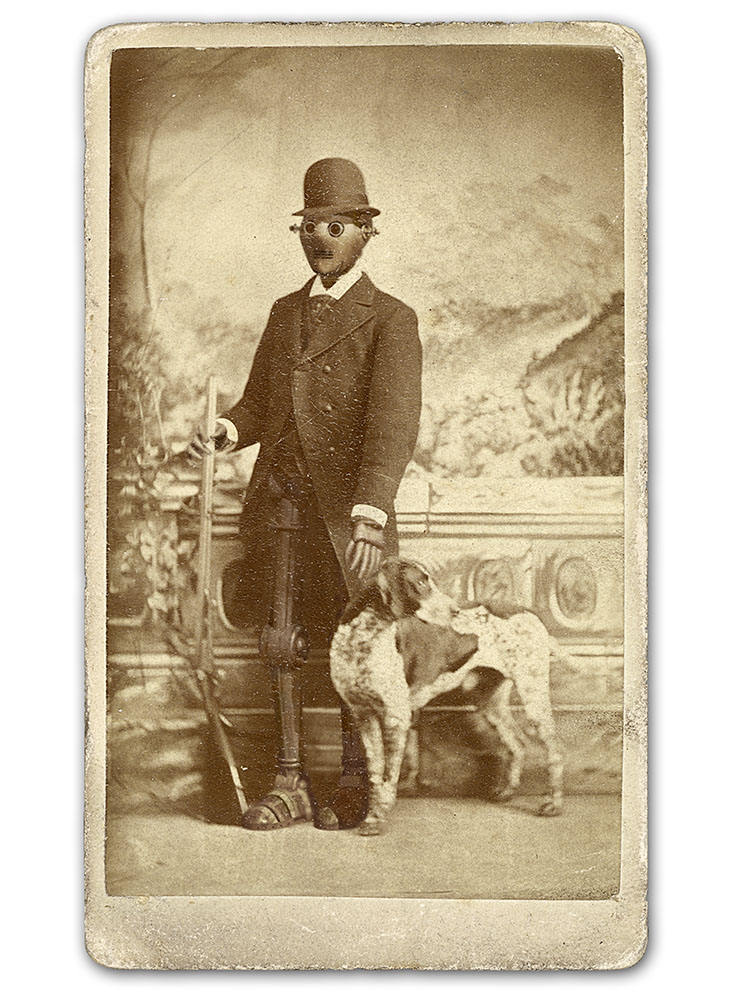

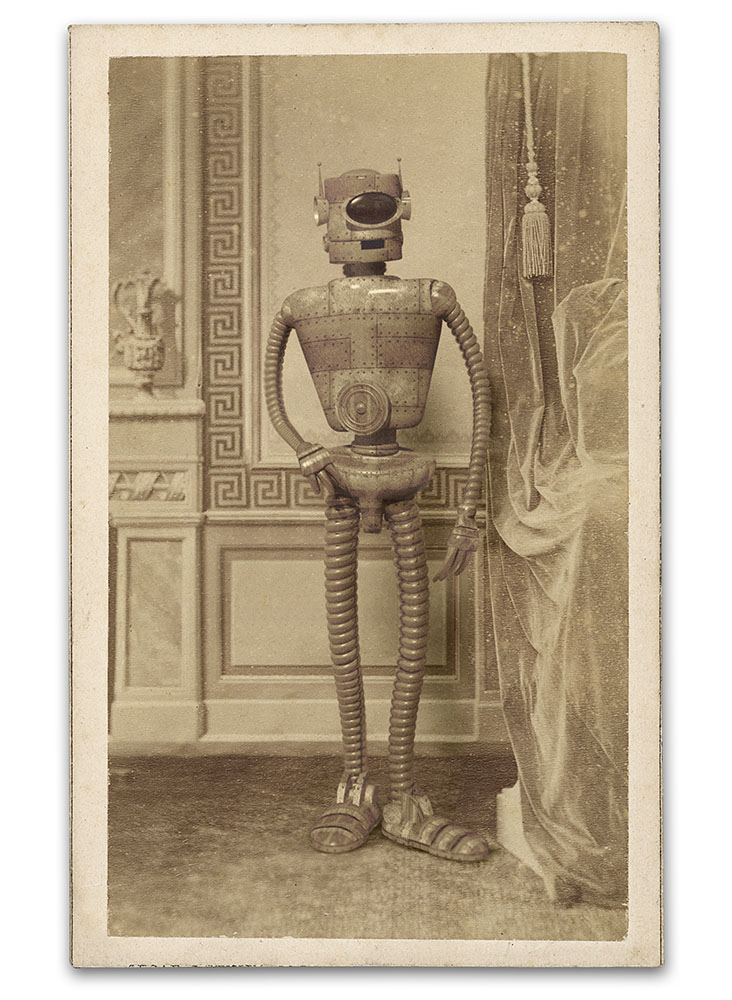

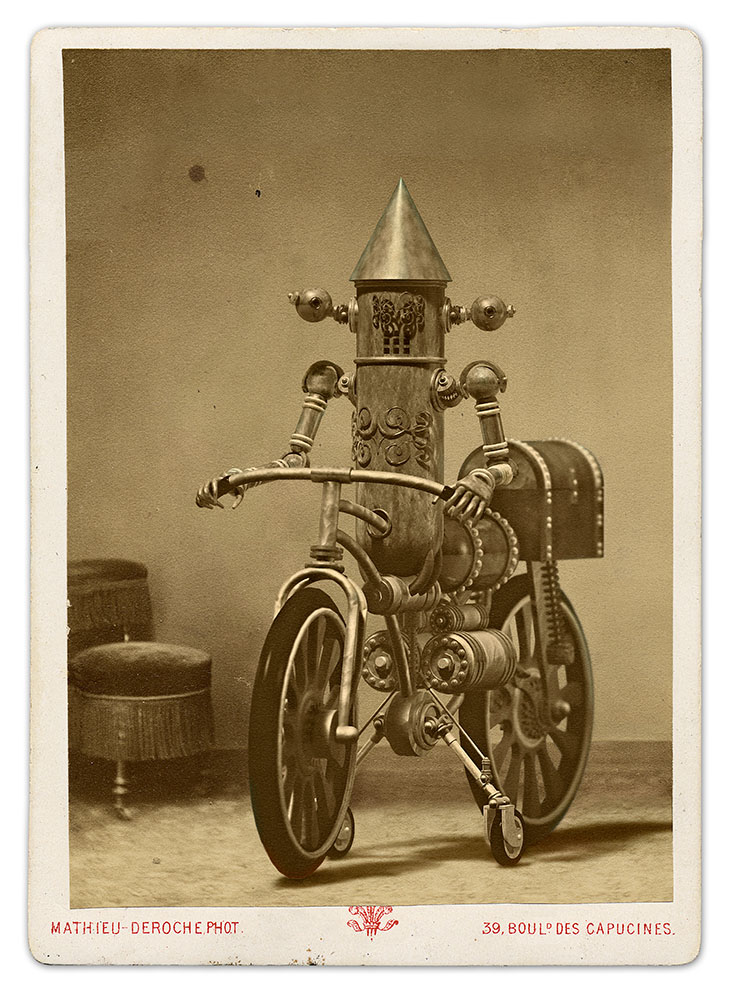

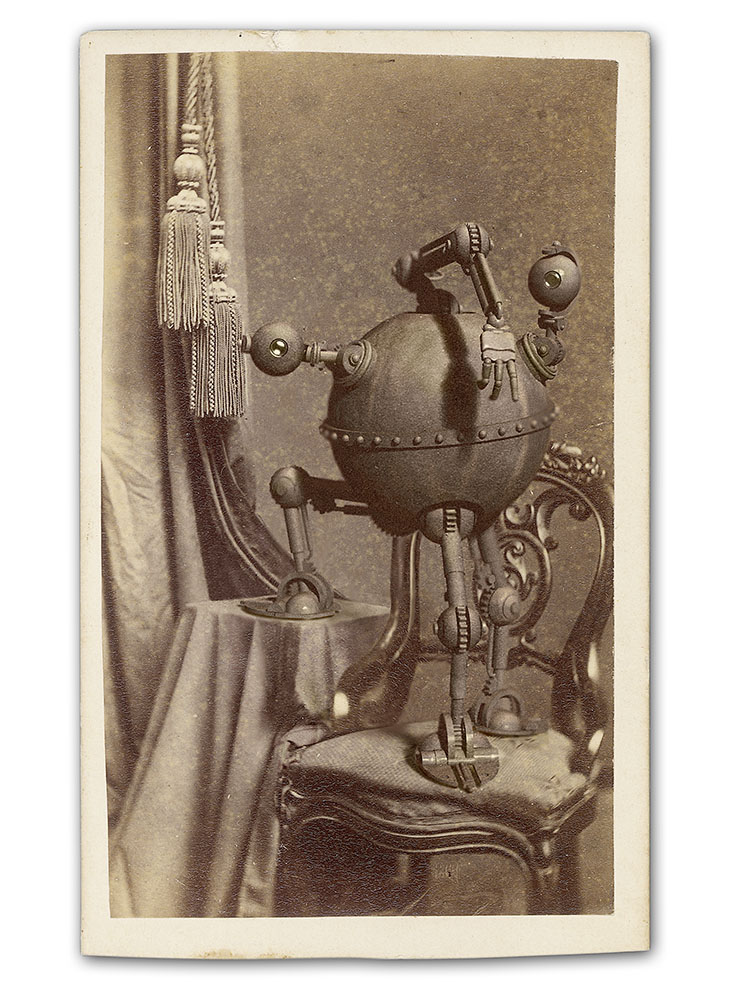

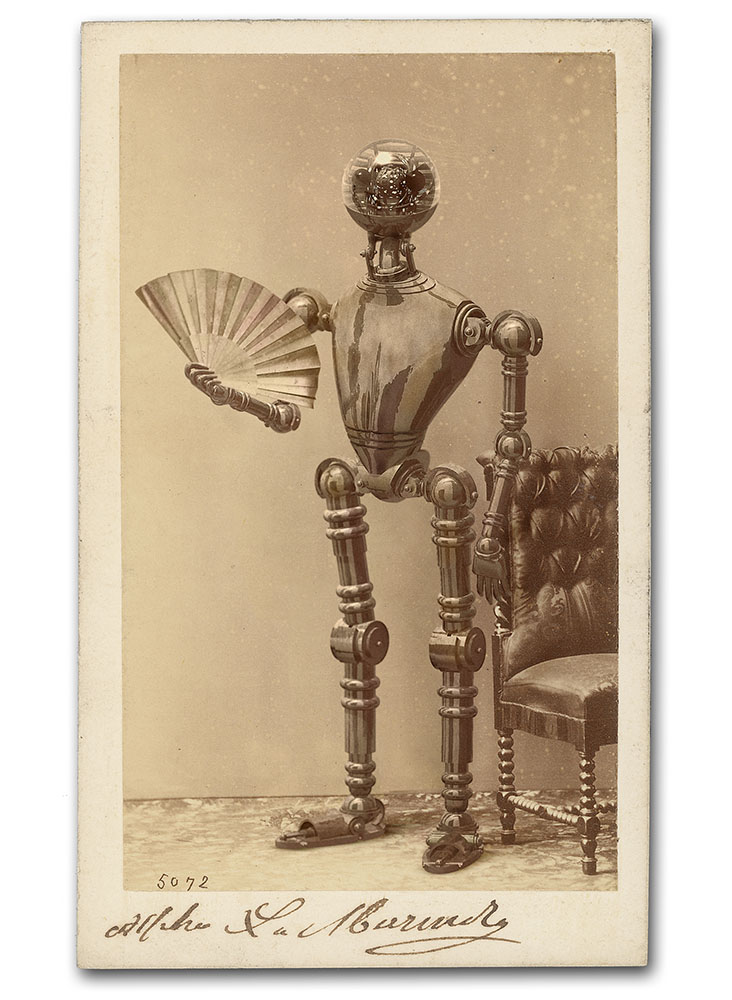

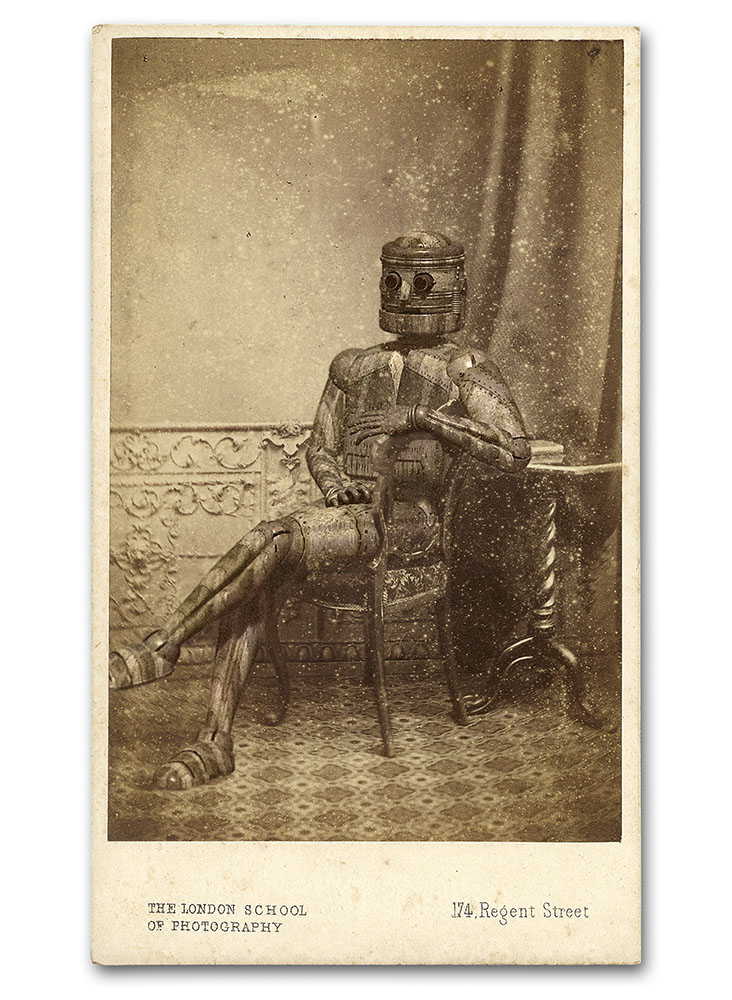

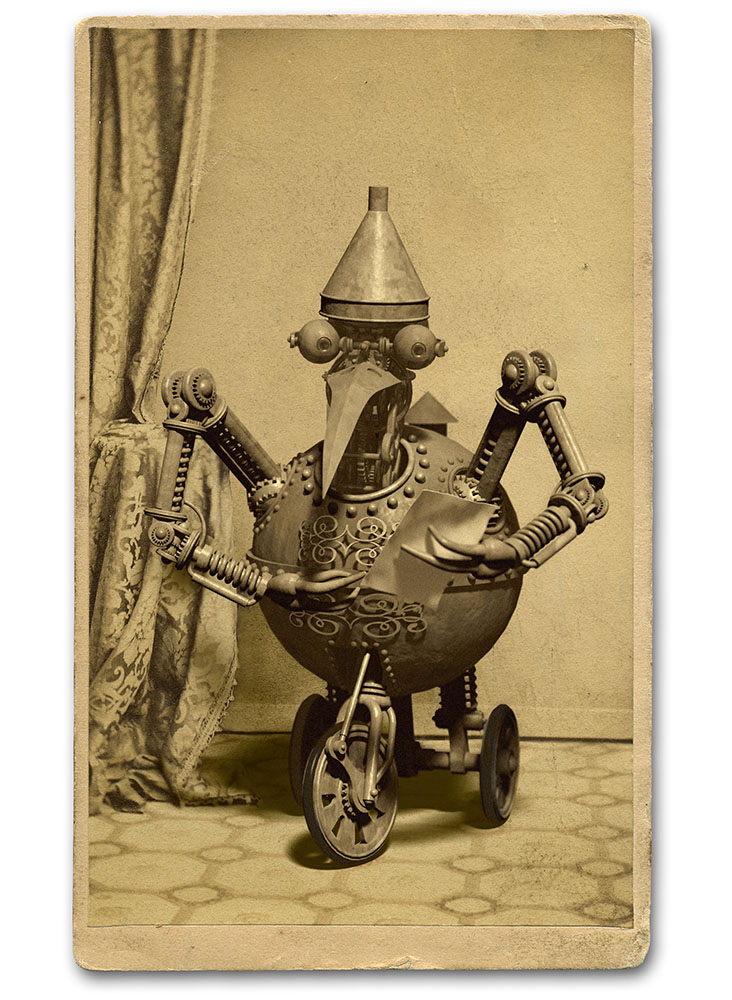

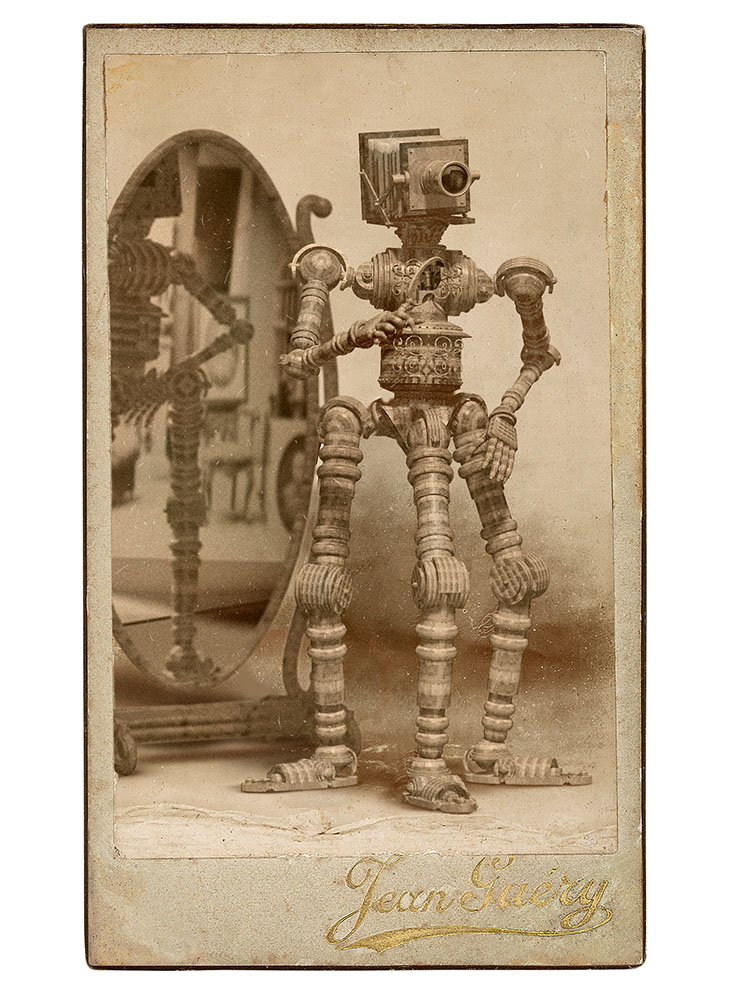

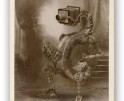

In his series Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny, Edward Bateman occupies the role of both inventor and philosopher. Using the carte de visite – the calling cards of the mid 19th century – as a historical and visual point of reference, he replaces the human subjects with mechanical automatons who take on the characteristics and idiosyncrasies of their human counterparts. These robots exhibit the qualities of human frailty: gestures of fatigue, expressions of curiosity, or implied companionship.

Embedded in this work is the question of evidence as Bateman does not present these images as his own creations, but rather as authentic and rare artifacts from history, salvaged from the oblivion of estate sales and ebay. He weaves a narrative that is utterly believable and yet fiction. I have witnessed Bateman present his work to an audience. Interspersed in his lecture about images and processes of photographic history, are the carte de visites from Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny. So compelling and seamless is this presentation and the exquisite rendering of his images, that one begins to doubt the chronology of the photographic timeline. Were there robots in 1859? In staging this narrative Bateman presents a past where the future of technology already exists, and mechanism and collective memory collide.

Edward Bateman is an artist and professor at the University of Utah. Through constructed and often anachronistic imagery, he creates alleged historical artifacts that examine our belief in the photograph as a reliable witness. In 2009, Nazraeli Press released a signed and numbered book of his work titled Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny, that explores 19th-century automatons as a metaphor for the camera, stating: “For the first time in human existence, objects of our own creation were looking back at us.” This book can be found in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harvard University, Art Institute of Chicago, Stanford University, Getty Research Institute, New York University, Columbia University, Amon Carter Museum Library, and George Eastman House, among others. In 2012, he was profiled in the UK publication Printmaking Today, the authorized journal of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers. He has been twice short-listed for the Lumen Prize, described by The Guardian Culture Blog (U.K.) as “The world’s preeminent digital art prize.” Bateman and his work has been included in the third edition of Seizing the Light: A Social and Aesthetic History of Photography by Robert Hirsch. His work has been shown internationally in over twenty countries and is included in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, The Victoria & Albert Museum, Getty Research, the Pforzheimer Collection of the New York Public Library, Harvard University, Cornell University, Brown University, and others.

Mechanical Brides of the Uncanny

In 1839 the first machine of depiction was created: the camera. It was a golden age of progress and anything seemed possible. Change came rapidly; it was a time of wonders.

Writing was the first technology to preserve memory – but the advent of the camera changed everything. The immortality of the photograph (even if just private), was intoxicating. People began to document the world around them. For the first time in history, people could now own their own image. With those images, memory began to become a concrete thing. The past was now something physical.

The dreams and images of artists have always been a source of inspiration and change for the world at large. Twenty years before the advent of photography, Mary Shelley wrote her novel Frankenstein. This could have been a driving force in one of the most significant, yet strangely obscure developments in the history of technology.

Automatons became the next wonder of the age, and the camera turned its ever-hungry gaze on them as well. This was an unprecedented development. Mankind had always looked at objects. For the first time in human history, objects of our own creation were looking back at us. Robots (although that name would not be coined for 80 years) made excellent photographic subjects because of their ability to remain motionless for extended periods of time. And indeed, they were widely documented, although few examples remain today.

This collection documents a sampling of cartes de visite selected to show the range of identities and roles filled by these mechanical creations. The carte de visite was an immensely popular form of photography patented by Disdéri in France in 1854. The name comes from the size of the cards: approximately that of a visiting card. They were widely traded and collected with subjects ranging from portraits of everyday people to the luminaries of the time. Memory and change now marched hand in hand, creating the world we live in today and leaving behind worlds that only exist in images.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Christine Baczek: The States Project: UtahOctober 29th, 2017

-

Josh Winegar: The States Project: UtahOctober 28th, 2017

-

Daniel Everett: The States Project: UtahOctober 27th, 2017

-

Fazilat Soukhakian: The States Project: UtahOctober 26th, 2017

-

Edward Bateman: The States Project: UtahOctober 25th, 2017