Aspen Hochhalter: The States Project: North Carolina

There are photographers who make work about photography—the act of making a picture is primary rather than the picture itself, seeing how the world looks photographed by them, etc. We learned about them in school. We teach their images and ideas in our classrooms. Our relationship with photographs has changed significantly in the last twenty years. Making photographs about photography is a much more complex endeavor these days. The accessibility to cameras and the ease with which we can share images boggles my mind. How can the photograph be precious if millions are made and shared everyday? Who is a photographer? What makes a photograph good or have value? Is it a photograph if its never printed? If we use historical printing processes does this change the value or nature of the image?

The nature of our image consumption is ridiculous. As photographers, artists, and educators of image making we work against this rabid form of capture and release. Instead we nurture the decision to make an image; revel in processes and ideas; covet the photograph. Most people do not have this relationship with photographs. It is easy to forget that we’re the strange ones! Aspen Hochhalter’s project encourages conversation on and investigation of these shifts in our relationship to photography.

Over the last six years I’ve had many discussions with Aspen about photography, teaching, tools, how we manage all the hats we wear, etc. As we discussed this feature and what work I would choose, it came out that she’d been working on something for several years but it wasn’t on her website and she wasn’t sure she wanted to share it, ever. She emailed me a couple examples. My head exploded a tiny bit and I knew I needed to convince her to let me share the work. Why is it that we are unable to take the advice we give our students? Why are we so unsure of the things we make, particularly if they challenge the notions of our medium that we were taught once upon a time? Aspen and I were unable to come up with any answers to these. We did have some fantastic conversations about the things we love: photography, process, and teaching.

Aspen Hochhalter was born and raised in Chipita Park, Colorado. She received her Masters of Fine Arts in Photo Based Media at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina and her BFA in Photography from Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. She is an Associate Professor of Art and the Photography Area Coordinator in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. Her work explores the crossover between digital technologies, historic processes and the use of experimental materials through appropriation, self-portraiture, and collaborative projects. Recent accomplishments include work published in The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes: 3rd Edition, McColl Center for Art + Innovation Residency, exhibits at Pease Gallery CPCC, Castell Photography Gallery, East Carolina University, Kiernan Gallery, The Light Factory, and many other venues across the country. She serves on The Light Factory’s Board of Directors and is active in the Society for Photographic Education, serving as a member of the National Board of Directors.

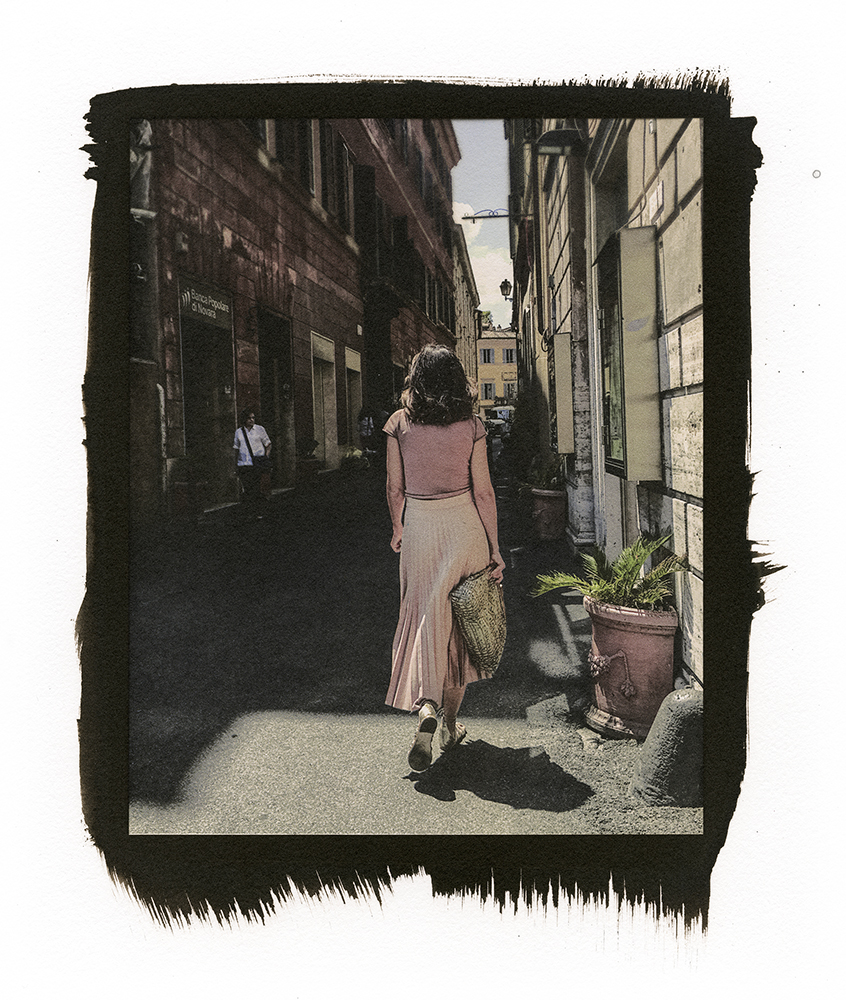

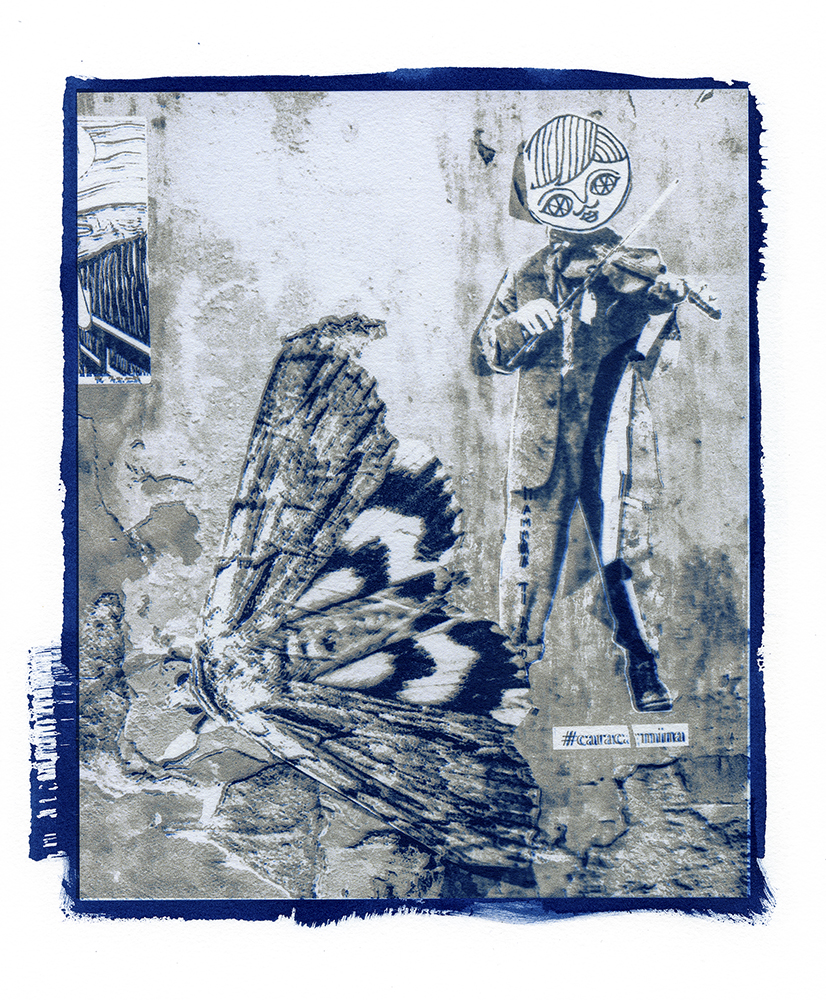

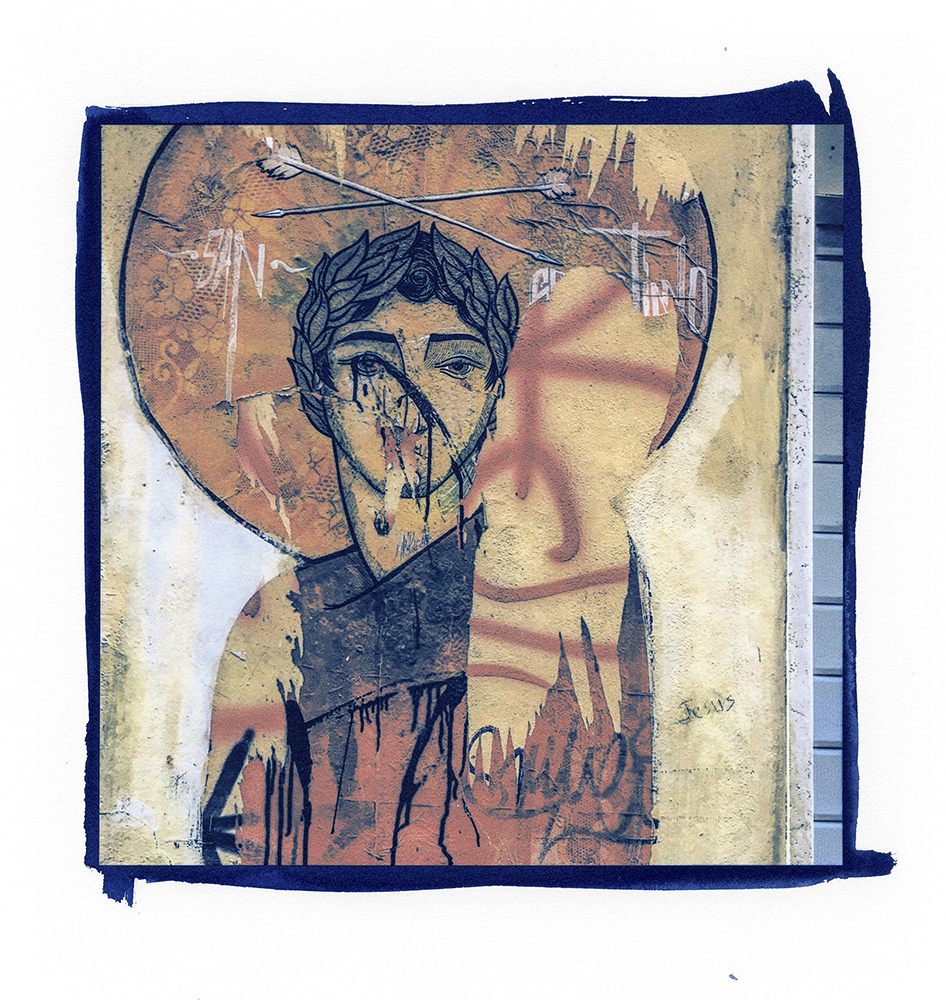

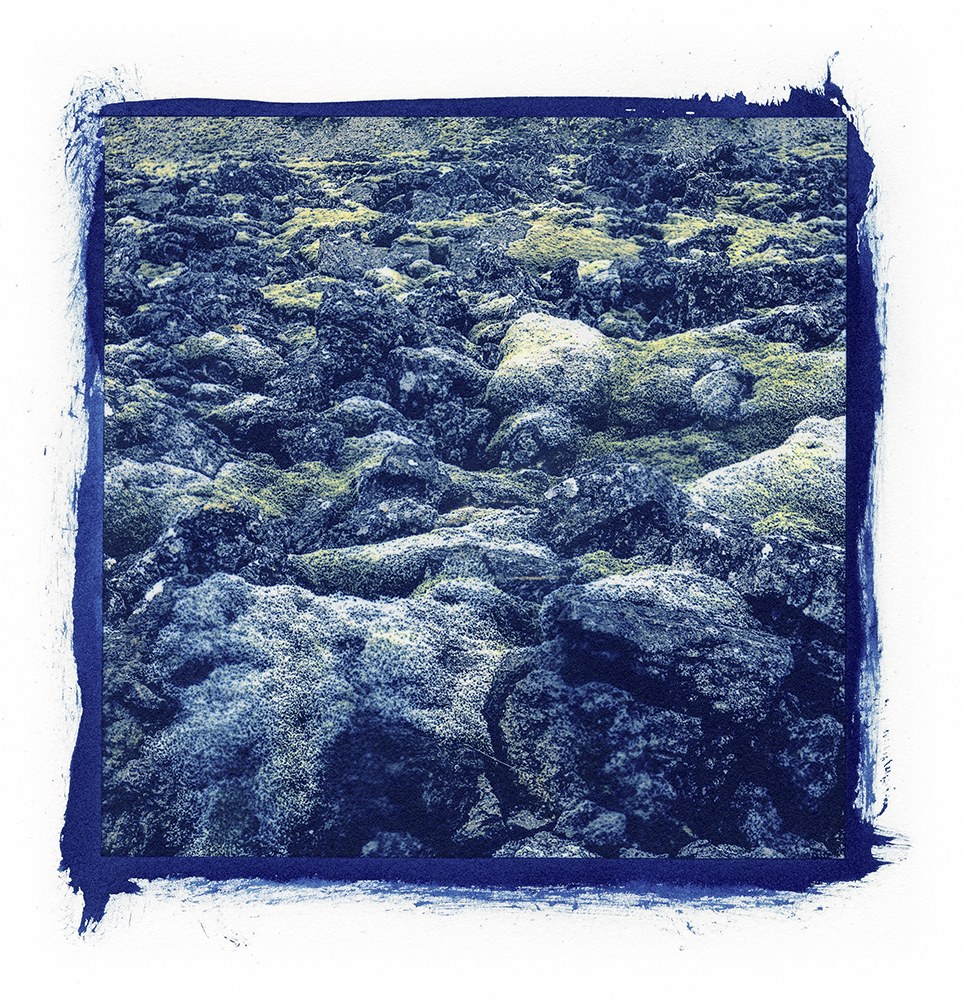

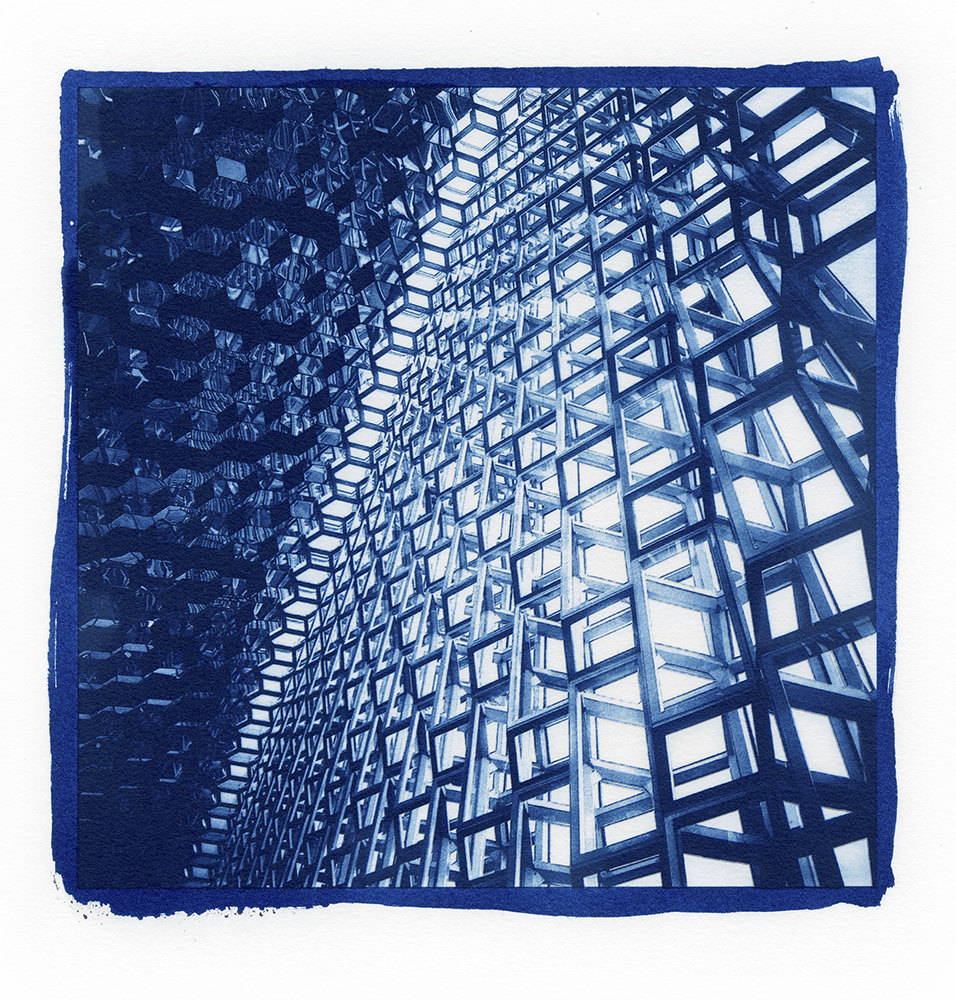

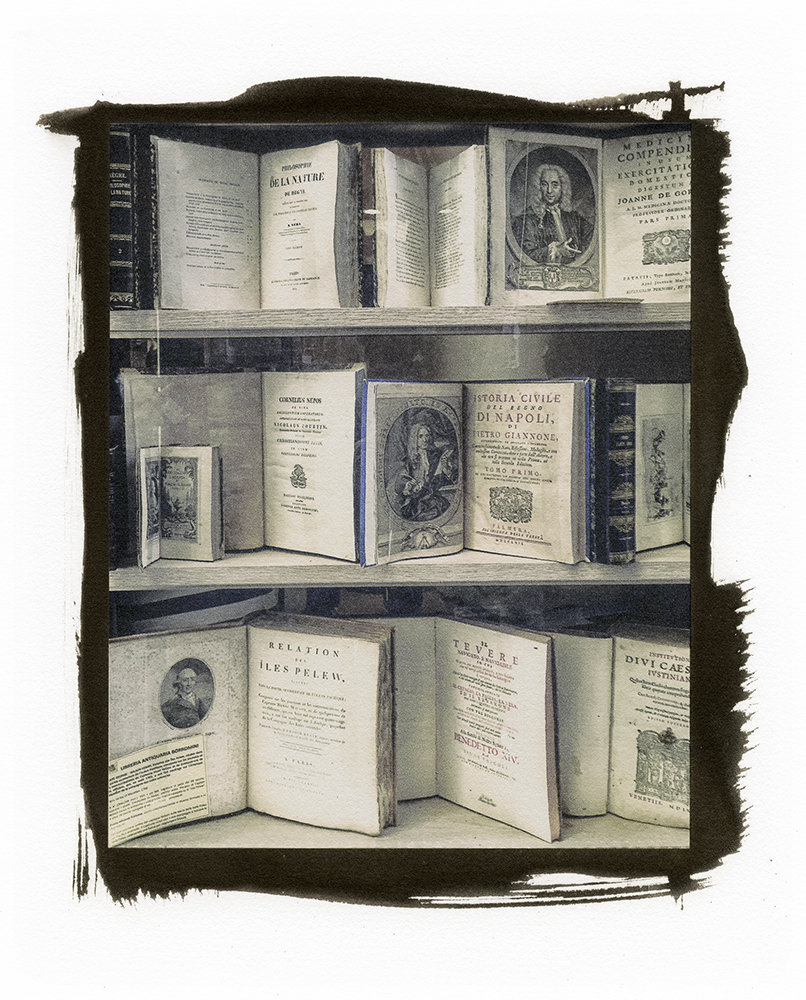

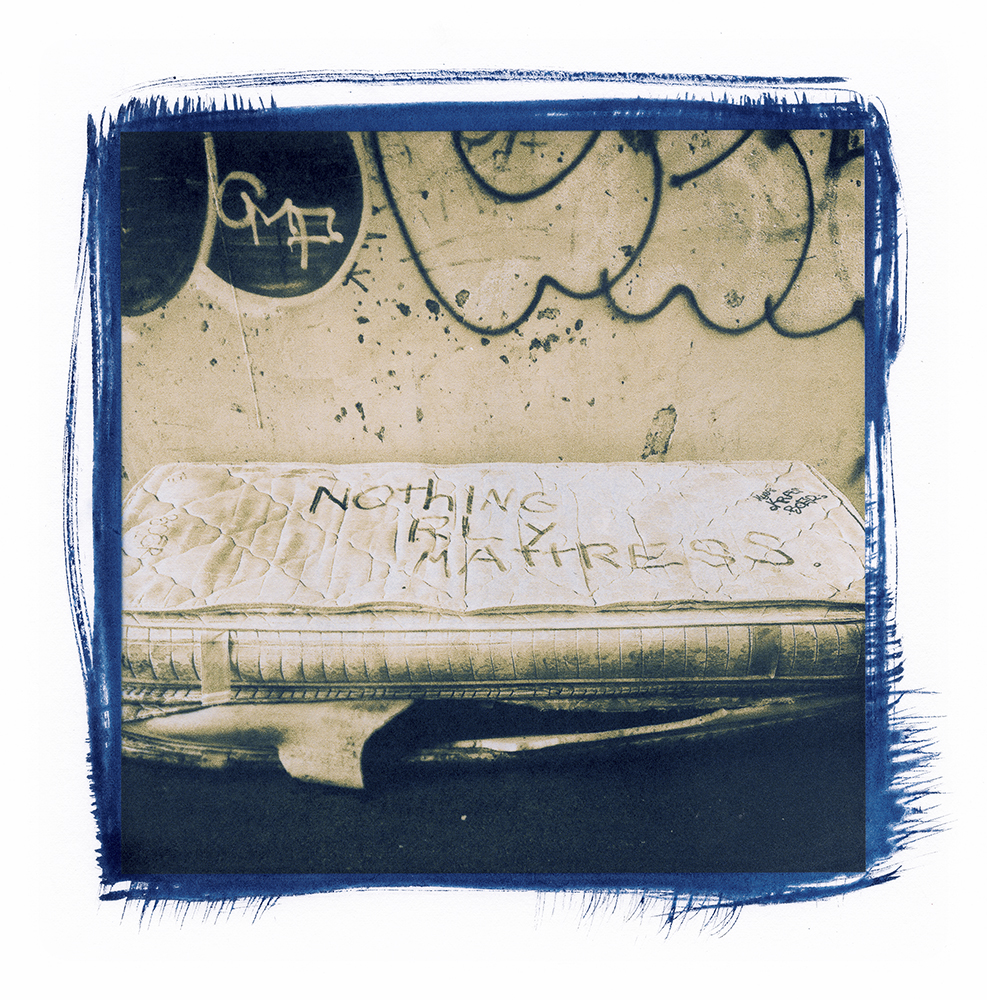

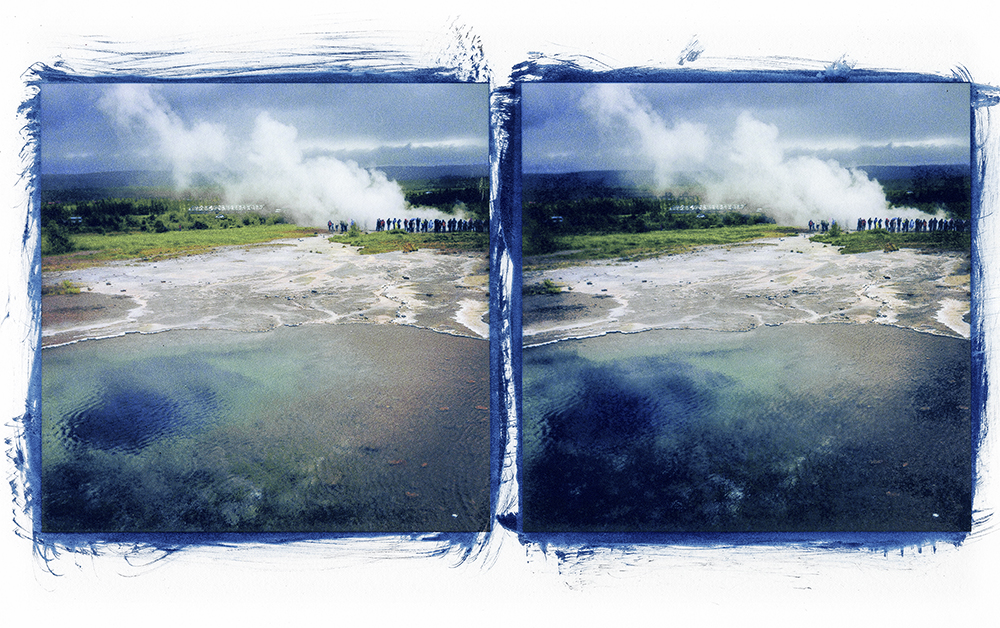

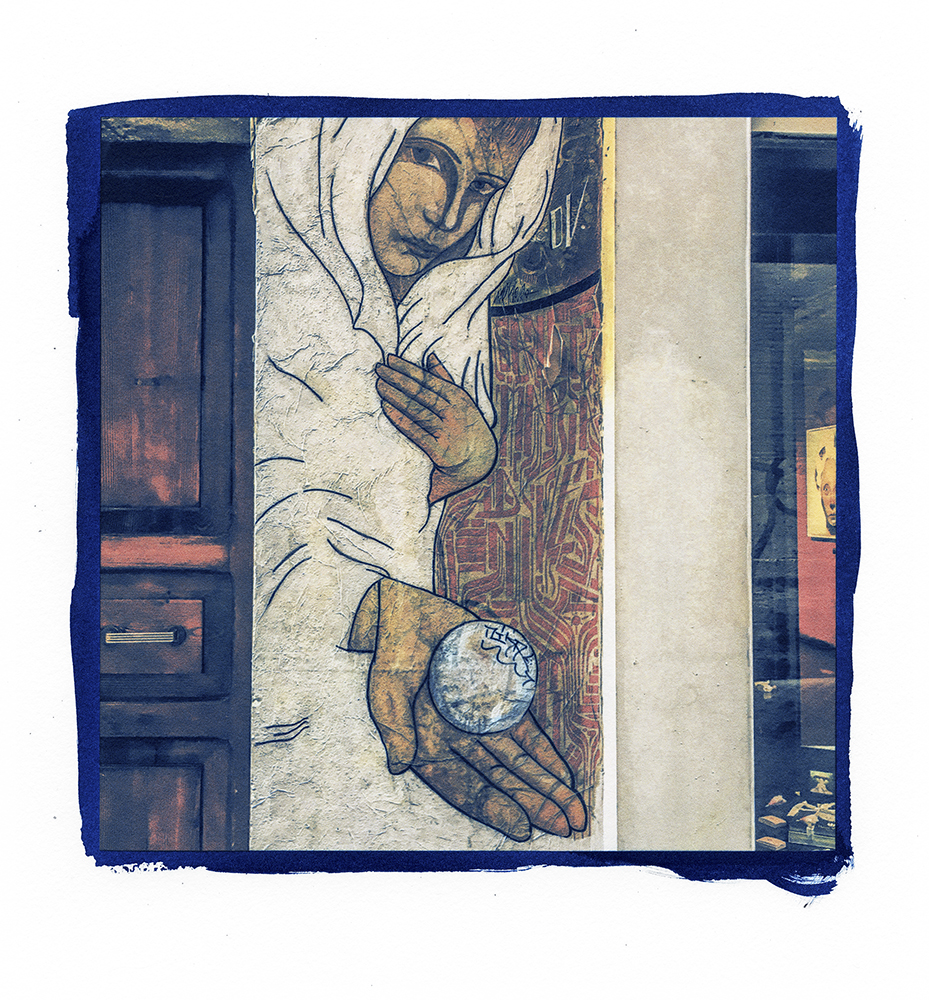

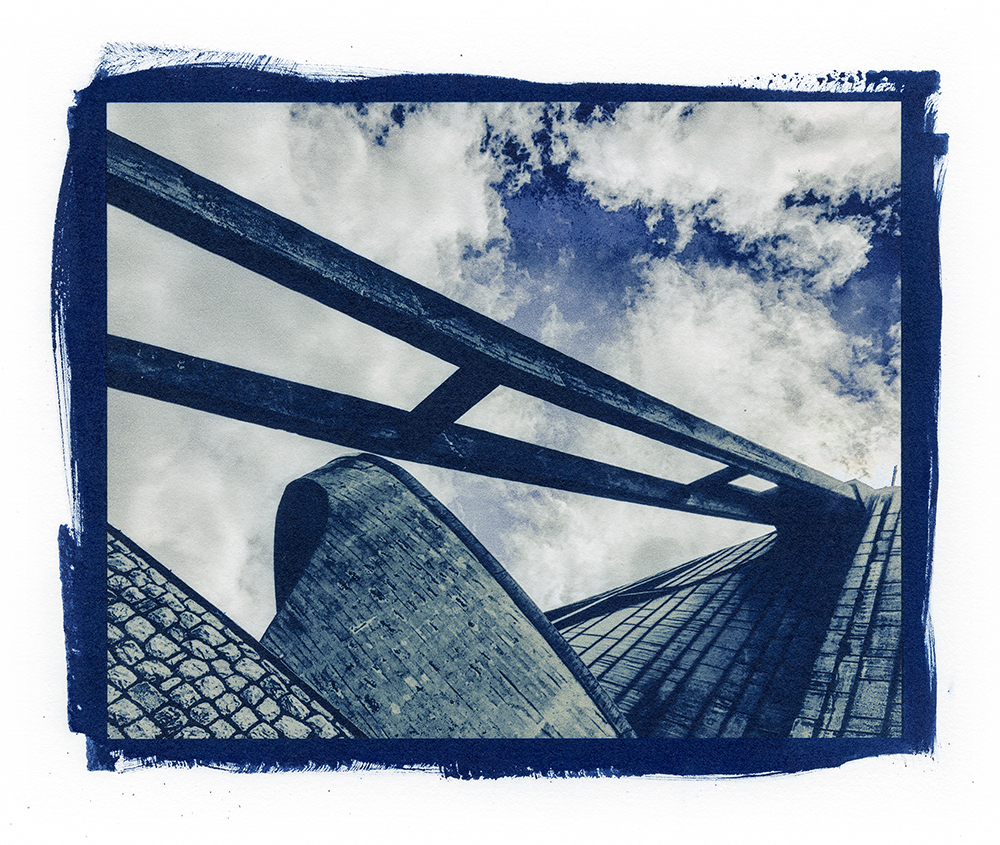

These images originate from Aspen’s Instagram feed from her travels to Iceland and Italy.

When we spoke you used a term I’d never heard before, but I think it may be a new favorite: Research Paper photographer. Will you describe and elaborate on this fabulous descriptor?

This is a term I’ve used over the years, and as I sat down to explain what I mean when I use it, I realized some interesting things. As a process oriented photographer it’s really a reflection on my own personal aesthetic and why I am drawn to photography as a poetic art form. I’ve come across many examples of work that requires so much context, so much explaining for the relevance and content of the photographs to become clear, that the photographs as visual objects almost become secondary to the concept. I think a lot of the times, the deadpan aesthetic is hijacked in this type of work, and sometimes it’s assumed that the use of this particular style automatically grants the work relevance. However, there are such rich bodies of work out there that use it to illuminate ideas and subjects in ways that are brilliant—it’s a tool, and it can produce absolutely amazing results. Yes, I’m being very critical, but it gets frustrating when we forget that art can be aesthetically interesting, full of life, be a pleasure for the viewer to contemplate while also being conceptually rich, thick with research, and sophisticated. Now on the other hand, I realize that the work that I do can operate in a similar vein in which viewers may feel the process overshadows or supersedes the content—work that aestheticizes the technical to the point where we fetishize the object-ness of the work. I think both of these approaches are a response to our rapidly changing medium—perhaps we’re in identity-crisis-mode trying to figure out what photography really is now that everyone has a camera in their pocket. I suppose it comes down to what each of us wants to pursue in our work; and with our medium in such a state of flux, we all have the chance to push at its boundaries, to expand the definition of what constitutes a photograph–what a fantastic opportunity for invention and exploration. In the end, I truly admire work that has found that wonderful, delicate balance of intellectualism and aesthetic power–and that’s what I would like to strive for in my own practice as well.

Taking pictures as a tourist and making images as an artist are typically considered very different activities with particularly different outcomes. We chatted about our shared experiences of this in Italy—specifically Rome and its hordes of tourists. How do you navigate your appreciation of the process and coveting the preciousness of the photograph with the desire to make these fleeting documents of experience, highly shared and public experiences?

As I reflect upon my years as a student of photography and now as photography instructor, I recognize a situation that I’m certain many post-graduates have experienced: I started to define my practice in very limited terms, with very limited subjects and assumed that when I made work it needed to be serious and conceptual in order for it to be relevant. This pressure is, of course, a bit stifling to a creative practice; given that the photographic medium is absolutely saturated on social media, the expectation or pressure to produce a culturally and intellectually impactful image is what a self-conscious academic photographer can feel at times. Photographic artists have a particular challenge to have their work somehow stand out amid the billions of photos taken every year. The as-yet-unnamed project featured in this post was started simply for fun—to explore the simple act of framing an image in the viewfinder, of finding those magical decisive moments, and sharing them. It also was meant to poke fun at my own Instagram obsession while allowing myself the room to experiment and to just make!

A quick digression: I’ve been to Rome about three times now teaching during the summers, and each time I am astonished by the number of tourists. In 2014, I had a very visceral moment at the Trevi Fountain: I sat there for a few hours just observing the hundreds of people crammed into this small space, and that year, apparently the iPad was the camera of choice for tourists. There were so many iPads up in the air watching their IRL experience through a screen. As Fred Ritchen puts it in After Photography, people prefer the commodification of their experience to the experience itself. It was at that moment that I decided I didn’t want to take any photos of the fountain, why would I have to, I could just search for photos taken on that particular day, time, and location, say, on Flickr! Silly and reductive I know.

Two years later in 2016, I had a little personal photo revolution while in Rome, and it was all thanks to my colleagues and Instagram. That summer, we really got into posting photos of our experiences throughout the day, and actually had a bit of an unspoken photographic competition between us. I’ve never been a street photographer, and never have had any interest in that kind of work (see comment above!), but using my cell phone all summer I took thousands of photographs with the intent of simply trying to find one little Instagram gem for our group. I was absolutely in love with my cell phone camera, the convenience of its casualness (I wasn’t taking it too seriously—after all, they were just cell phone photos!), and there was an immediate, tangible reason for making the work: I could instantaneously share them with an attentive audience. As my friend Antonio Martinez observed, “You rediscovered what it means to be an amateur, literally, you did it for the love. Love=amor=amateur.”

After returning from my travels, I wanted to engage with them more than just posting it once on Instagram where their life as a photographic experience was already dead—my audience had looked at it for the time it took to “like” it and then swipe up to the next photo. This was a very unsatisfying realization: the photos on Instagram were cheap, quick pixels that were rather instantaneously digested, critiqued, and discarded.

Inspired by the amazing Diana Bloomfield and her alternative process over inkjet prints, I started to explore this combination printing with my instagram posts—and I specifically started to do this for two reasons: I wanted to learn the process and I thought these particular photos that were born of Instagram were a great digital starting point for the combination of digital and chemical printing, or as I call it, Alt+Ink. Secondly, I wanted to make beautiful prints that I could give away to family and friends—handcrafted, one of a kind photographic prints produced with my time, labor, and knowledge of wet processes.

So, interestingly enough, the heart of the project is not only a play between digital and traditional tools and techniques, but a return to thinking about the philosophy of sharing photographs and the way Instagram or Facebook or any other social media platform has changed the way in which we not only ingest photos, but share them. While these social media platforms are about sharing experiences on a virtual platform, this project strives to memorialize and materialize the shared experienced.

Our relationship with photography and images seems to be literally constantly changing. Where do you see it moving in the future? How (if at all) can we prepare for this as artists and as educators?

I have come to realize that we are lucky to be in such an interesting point in the evolution of photography. Yes, as I mentioned above, it is hard to find ways to stand out from every other person with a camera, but on the other hand, we’ve never been more connected as a community with resources and support readily accessible via FB groups, websites, and simply email. So yes, our medium is shifting and changing so fast and in interesting and unexpected ways, but I think the foundation for a life-long creative practice is the same as ever, we just have the added opportunity to push the development of our medium in whatever directions we want!

When I think of our medium’s future, I really think about my students and try to pinpoint exactly what I want them to know when they graduate. I’ve come to the realization that if I can only instill one thing in my students, it’s that I want them to be someone who leaves our program addicted to making work. Someone who lives, eats, and breathes making; who is full of curiosity and has the ability to jump-start their own learning and experimentation. I want them to build creative lives, not necessarily in academia, nor necessarily anywhere near the arts professionally and honestly it doesn’t even have to be photographic in nature. If they can just keep that creative drive in their life no matter what they do, I think that will be a success and will prepare them to engage with whatever the future holds for photography, technology, and the art world—not to mention whatever career they decide to pursue. If you haven’t read Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert, I highly recommend it. She basically lays out her manifesto for living a creative life, and I try to read it at least once a year to remind myself of this goal for my life—and also so I can pass that philosophy on to my students.

How does teaching influence your creative process? Feel free to be candid!

Teaching is honestly my biggest inspiration at the moment, I love being in the labs with students exploring ideas, methods, and materials. Their excitement, innovation, and motivation keeps me excited to be in the classroom. As educators we have such a unique and wonderful opportunity to be renewed by the continual flow of students learning not only photography for the first time, but all subjects, and the interesting ways in which they attempt to translate their new knowledge into work. Their eagerness to learn is what inspires me to continue my own explorations—I would say that is what drives my creative practice at the moment, the desire for new knowledge and the deep dive we take as a class into whatever new process or idea catches our fancy.

This deep diving into topics/processes really began a couple years ago when I started teaching a once a week six-hour Alternative Process class on Fridays; it literally becomes an intense weekly workshop of ideas and techniques. However, what makes it truly a success is the dedication of the students; they are in our facilities all week working for the Friday class. We do not have a graduate program at UNC Charlotte, but this Friday experience has generated that whole-hearted passion and energy that graduate students bring to a program.

The Alt+Ink technique is a good example of how far they push themselves—some of them really took it to a whole new level. There are many artists out there utilizing this combo printing technique in interesting ways, and I think the challenge for any new tool is to eventually figure out how to push it beyond mere mimicry of other types of aesthetics, and truly be innovative. I have definitely not gotten to that point yet with Alt+Ink, but some of the ways in which my students are exploring these two mediums together are really interesting—they are using them in ways that I’ve never seen before, they’re not simply trying to replicate a color photo or even a gum print, they’re exploring the inherent qualities of both the ink and alt process and how they can use each to make a totally new aesthetic, one that’s unique for this new process.

I’m sure many educators have this same experience, feeling like we’re getting really good at writing reports or filling out paperwork while watching with excitement as our students push themselves beyond their expectations. I feel so fortunate to be in the classroom. Their growth really is my biggest inspiration!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Lorraine Turi: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 19th, 2017

-

Aspen Hochhalter: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 18th, 2017

-

Leah Sobsey: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 17th, 2017

-

Ryan Adrick: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 16th, 2017

-

Courtney Johnson: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 15th, 2017