Leah Sobsey: The States Project: North Carolina

The choice of what to include in an image frame can completely transform a photograph’s meaning. This is one of my favorite aspects of our medium. The slight shift of the camera in one direction; the quick removal of an object; using shallow depth of field to blur the background—there are so many mechanisms with which we the image-makers may use to conceal or reveal information. Leah Sobsey’s project Collections opened a flood gate of questions for me based on her varied methods of providing detail, removing context, and pushing several processes and tools to play with one another simultaneously.

Collections is an umbrella for what I initially thought was 10 small typologies all of which culminate in a book. After speaking with Leah, I realized that Collections is a way of making and creative problem solving for her. The body of work is the result of over 10 years of examining artifacts, animals, remains, and information from multiple collections all over the United States. The evolution of the project is a result of balancing available tools, access to specimens, value to the region where the artifacts are housed/found, and her own personal interests. Leah’s background in cultural anthropology is apparent in her systemic analyzing of form and function with each artifact. She simultaneously examines the singular item and how it connects to a community of objects. The single object is of value, its isolated allowing its shape, form, and detail to be exalted. However it isn’t until it becomes part of the whole that we begin to see its purpose.

Leah Sobsey works in 19th-century photographic processes combined with digital technology. She exhibits nationally in galleries, public spaces, and museums; her most recent installations were exhibited at The Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, 21C Hotel Museum in Durham North Carolina and Rayko Photo Gallery in San Francisco, California, which also featured her first monograph, Collections, released in July 2016 by Daylight Books. Her work is held in private and public collections across the country, and was recently acquired by the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) for its permanent collection. She is one of the core artists in Bull City Summer, a documentary project that explores the Durham Bulls AAA baseball team, a Daylight Books best seller. Her images have appeared in New Yorker.com, the Paris Review Daily, Slate.com, Hyperallergic.com, The Telegraph, and Audubon Magazine among many others. She has taught at the San Francisco Art Institute, the Maine Media Workshops, Duke University’s Center for Documentary studies, and NCMA. Sobsey, the co-founder of the Visual History Collaborative, is an Assistant Professor at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

Collections

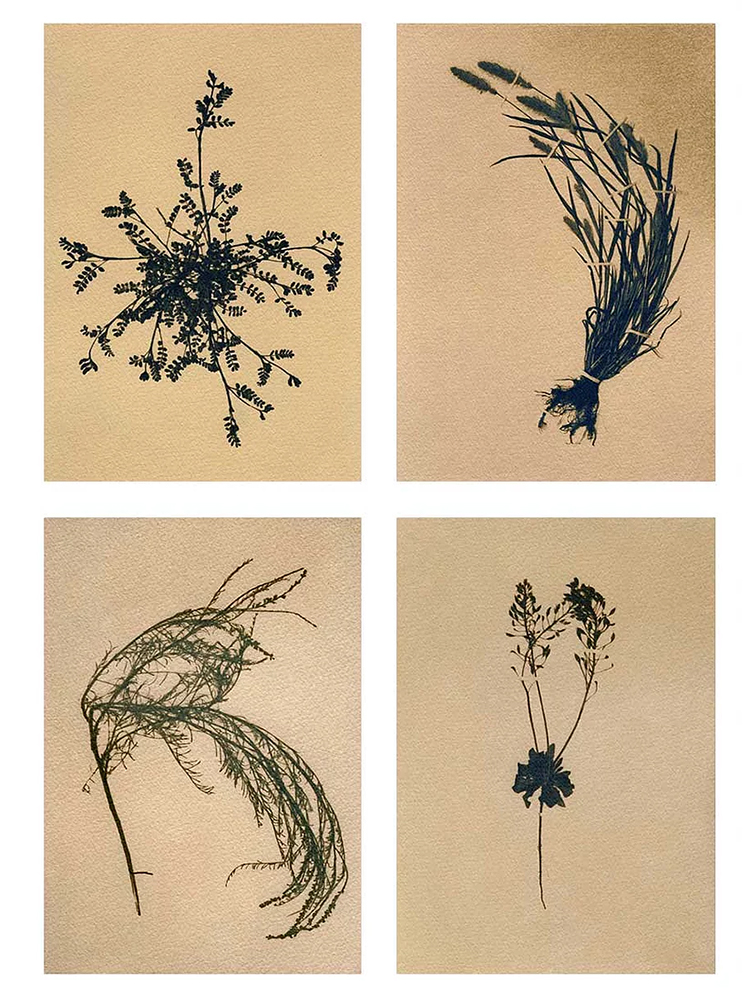

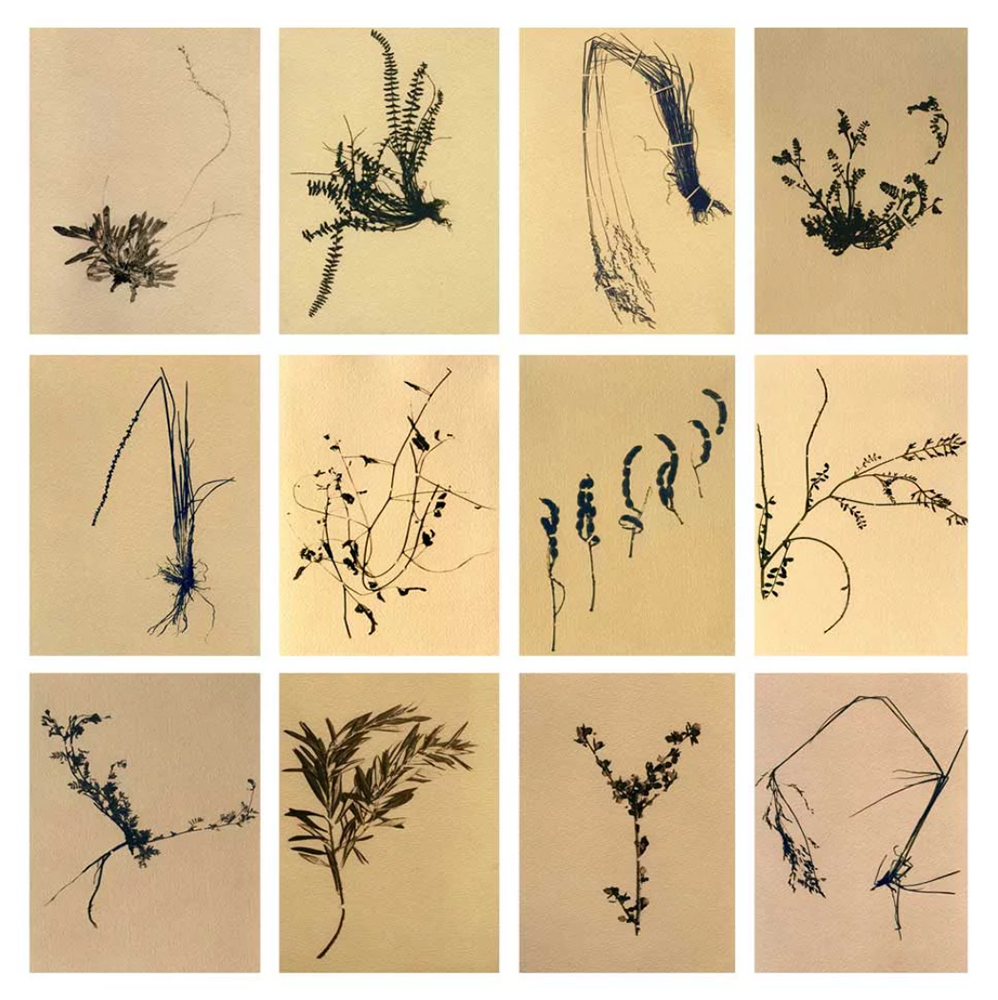

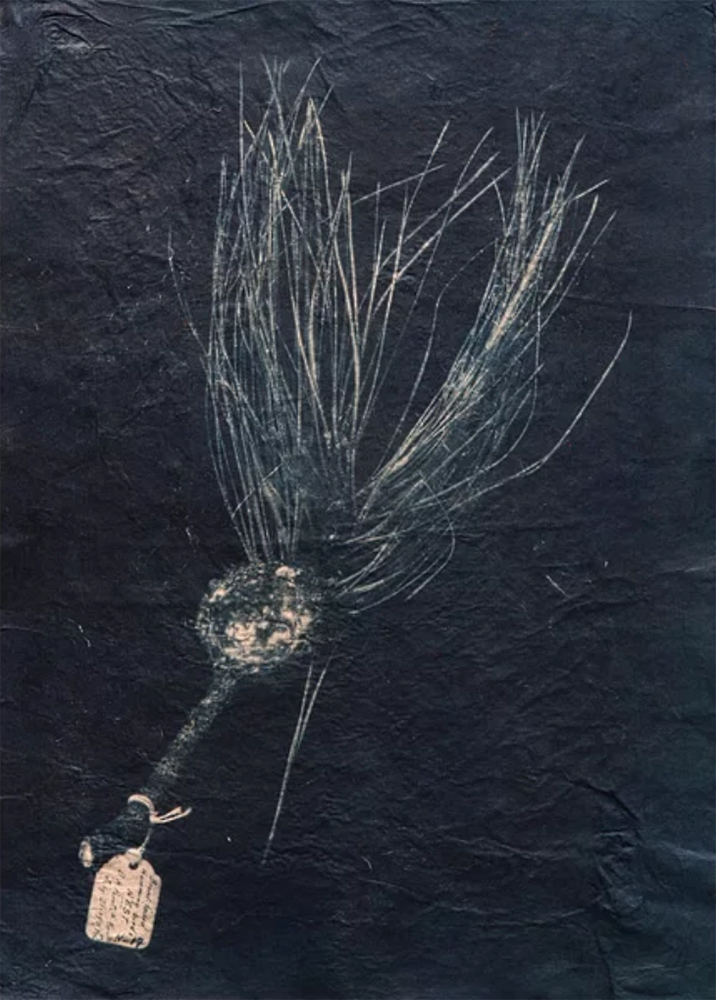

I became a photographer because of the medium’s power to reveal—metaphorically and literally. My earliest memories of the darkroom are of those exhilarating moments when an image first floats into view, slowly revealing its mystery. This liminal space of emergence, between obscurity and exposure, is at the heart of my work as a visual artist. My projects organize themselves around hidden troves. I am drawn to museum collections, science and natural history specimens, material objects, social units—assembled contents that have been neglected or forgotten, erased by anonymity, by time, by death, by darkness. In quiet contemplation, I touch, rearrange, and photograph these objects as I consider their archaeological value and explore new ways to bring them into the light. My work visually and procedurally recalls the scientific practice of taxonomy; however, where taxonomy sets out to document, define, contextualize, codify, and classify, my artistic practice reverses this inertia. In each collection I photograph, I seek instead to reanimate my subjects, unpin them from their histories, and erase their contexts. If the nineteenth-century pictorialists used process and manipulation to elevate the photograph from recorded image to art, I use photographic experimentation and contextual erasure to create a new poetics of taxonomy.

My most recent work, Collections (Daylight Books, 2016), is a culmination of a decade of photographing specimens in state and university science collections and national park museum collections. I received grants from the US National Park Service and collaborated with scientists at Duke and North Carolina State to access various science and natural history collections. The book contains images made from collections of birds, herbaria, butterflies, artifacts, bones, and nests. This book explores our constantly evolving and increasingly intertwined relationship to nature and science through my experimentation with historical photographic processes, processes that are interrupted, challenged, or complemented by my use of today’s digital technology. I directly reference and engage the nineteenth century, and artists like Anna Atkins, through composition, subject matter, and technical processes; however my conscious erasure of background and context along with the introduction of a digital process to the image’s creation surges the work into the present and breathes new life into a formerly dead specimen. On the one hand, I want to bridge the gap—technologically and metaphorically—between that frozen, archived history and a vibrant, dynamic present. On the other hand, by actively stripping both the background and the context, I make the objects appear to float, and thus dislocate them not just from history and place but from time itself.

The title Collection could be considered an adjective used to describe the way you see and look at the world around you. Throughout all of your projects you are seeing the subject as a part of the whole, as a collection. Can you share some thoughts on where this comes from or how you understand your desire to do so?

Growing up going to Quaker Schools, from kindergarten through college, one of the big lessons they drove home was the paradox of seeing each of us as unique individuals while being part of a whole community. That image of one within many, stuck with me. That translated to being a cultural anthropology major — studying communities and how they work as individuals within the collective society.

You have been working on Collections for over 10 years. Often the publishing of a book signals the end of a project, but in this case it is perhaps the end of a chapter. How has Collections continued to evolve for you and where do you see it heading next?

I’m paying attention to how I feel as an individual within the political and environmental climate. As a parent of 4-year-old twins, I think about the future. So, I’m looking to the past – to Thoreau’s collection because of the 820 specimens he collected, 30-50% of them are in decline or extinct. As an artist, I’m interested in demonstrating how art can bridge worlds, particularly how science and art can impact each other. I’m currently collaborating with Harvard Scientist (Emily Meinke), Professor of Film Studies at NCSU (Marsha Gordon), and UX and visual designer (Robin Vuchnich) to make this happen.

How does teaching influence your creative process? Feel free to be candid!

When I learned photography, the buzz about digital photography was: Well that won’t stick. Now, if you have a phone you’re a ‘photographer.’ My interest is in combining 19th century processes with digital technology – one foot in the past and one in the present and an eye on the future. When digital photography became a part of the curriculum, schools were closing dark rooms and I pushed to keep ours open. Now, a decade-plus later, students are knocking on my office door to enroll in dark room and alternative process classes. They are thrilled to be learning something “new”.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Lorraine Turi: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 19th, 2017

-

Aspen Hochhalter: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 18th, 2017

-

Leah Sobsey: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 17th, 2017

-

Ryan Adrick: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 16th, 2017

-

Courtney Johnson: The States Project: North CarolinaNovember 15th, 2017